CHAPTER 99 Spondylolisthesis: Medical Rehabilitation and Interventional Spine Techniques

INTRODUCTION

Patients presenting with lumbar spine complaints who have radiographs showing spondylolisthesis may experience painful or neurologic symptoms from a variety of clinical entities. The evaluation and treatment prescription should evolve from a biopsychosocial model that has been suggested for low back pain.1–8 Radiographic features, neuromuscular function, psychological, social factors and medical comorbities must be considered as a part of the overall disease when formulating the treatment plan. The most commonly used classification system for spondylolisthesis is based on Wiltse, Newman, and Macnab (Table 99.1).9

Table 99.1 The most commonly used classification system for spondylolisthesis

| Type 1 Dysplastic |

| Type 3 Degenerative |

| Type 4 Traumatic |

| Type 5 Iatrogenic |

Based on Wiltse, Newman, and Macnab.9

PATHOANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

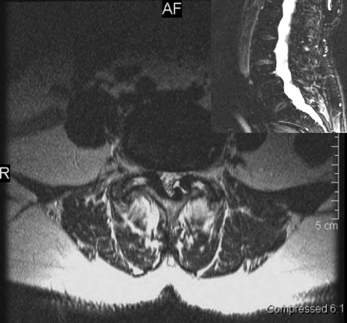

Degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS) is a segmental degenerative process characterized by facet joint arthrosis and segmental subluxation (Fig. 99.1).

Multiple causes may initiate the process of subluxation but facets with a sagittal alignment are probably an important contributing factor.10–12 As the posterior elements move forward with the vertebral body,13,14 the inferior articulating processes eventually can move forward enough to abut the superior endplate of the caudal vertebral body. This may explain why the degree of degenerative spondylolisthesis is usually only grade 1 or 2. Intervertebral disc space narrowing may occur simultaneously or later in the overall process.11,15 It remains unclear if the degree of subluxation has any correlation to the severity and presence of back pain or diability. Matsunaga et al. followed 145 patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis for a minimum of 10 years and observed no correlation between changes in clinical symptoms and progression of spondylolisthesis.16,17 The occurrence of increased translation or angular motion on flexion radiographs can be noted, although the relevance to different treatment outcomes is unclear

Those with DS may initially present with the insidious onset of low back pain with or without thigh pain that could be attributed to facet joint disease.16–19 Leg pain, which may occur in early stages, in the absence of significant spinal stenosis, is often quickly responsive to treatment. In the later stages both lateral and central spinal stenosis may develop secondary to zygapophyseal joint hypertrophy, ligamentum flavum buckling, and/or disc protrusion. Neurogenic claudication secondary to spinal stenosis causes referred pain into the buttocks and lower limbs while walking, and is relieved when the patient sits or bends forward. Degenerative spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis represents a more severe anatomic disease.20–24 There is evidence that patients presenting with severe back and leg pain who have radiographic findings of severe central stenosis will respond poorly to medical rehabilitation and interventional spine treatment.25,26 In addition to symptoms caused by central stenosis, entrapment of nerve roots within the lateral recess and intervetebral foramen may cause radicular symptoms. For example, a superimposed foraminal disc protrusion may cause symptomatic L4 radiculopathy. A posterolateral disc protrusion at the L4–5 or asymmetric facet joint arthrosis may cause unilateral radiculopathies affecting the L5 nerve root.

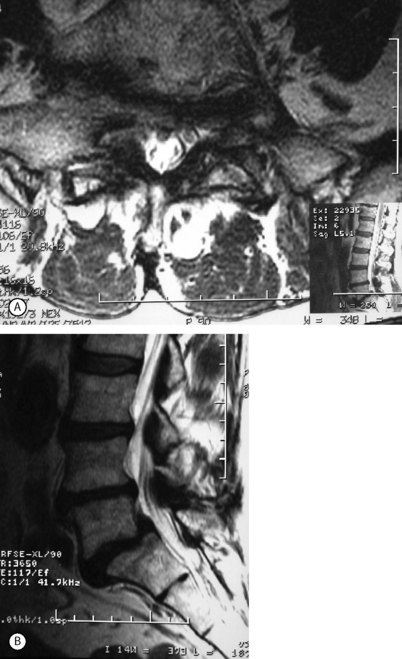

Isthmic spondylolisthesis (IS) is caused by a defect in the pars interarticularis which allows anterior translation to occur in the absence of facet joint arthrosis. The distortion of the foramina by the proximal pars stump may cause dynamic or static compression of the exiting nerve roots (Figs 99.2, 99.3).27–31

Although foraminal stenosis is common, central canal stenosis usually is absent in low-grade IS. In large measure, this is due to the fact that the most common level afflicted with IS is L5–S1; the most capacious portion of the spinal canal in the lumbar spine (Figs 99.4, 99.5). Clinical studies suggest that the amount of slip will not significantly progress in adult IS.32–38 It is also unclear whether isolated IS is a primary cause of chronic low back pain. A thorough evaluation of other causes of low back pain should be conducted in all patients who present with low back pain and IS.39,40 Recalcitrant episodes of unilateral leg pain, or back pain associated with leg or thigh radiation, may be attributable to foraminal radiculopathy. Symptoms unresponsive to oral medications and physical therapy will often respond to transforaminal epidural steroid injections.

MEDICAL REHABILITATION AND INTERVENTIONAL SPINE PROGRAM

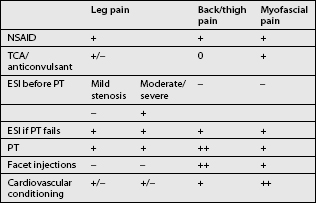

A step-wise approach to treatment can be divided conceptually into three independent but overlapping phases: pain control, stabilization, and a conditioning phase. Treatment interventions can include oral medications, behavioral modifications, physical therapeutics and therapeutic exercise, bracing, and a variety of injection procedures. Therapeutic decisions should be made on the basis of the clinical and radiographic evaluation. Categorizing patient complaints into back pain, leg pain, and myofascial pain can help organize treatment options (Table 99.2). Leg pain not directly attributable to radiculopathy may be caused by somatic referral, hip bursitis, osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, or myofascial pain.41

Oral medications

Medications for the treatment of various forms of lumbar spondylolisthesis have not been studied. In a large meta-analysis of low back pain,42 there is good evidence supporting the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications and acetaminophen in the treatment of acute pain, and fair evidence for the use of muscle relaxants. Using these medications may help allow the patient to continue in a physical therapy program. The efficacy of drug therapy for chronic low back pain is less clear. Current controversy surrounds the use of narcotic medication for chronic low back pain.43–46 Patients with significant radiculopathy can be treated with a course of oral corticosteroids and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication for 1 week. Although unproven, NSAIDs may be more effective in the treatment of DS because of the presence of facet arthrosis.

Anticonvulsant and antidepressant medications should be also be considered for all patients with myofascial pain and for patients presenting with dysesthetic leg pain, especially if the leg pain is nocturnal. Gabapentin has become one of the off-label anticonvulsant drugs most commonly prescribed in the treatment of spinal pain, and although the mechanism is unknown, a recent study suggests that gabapentin may be useful in the treatment of patients with neuropathic or myofascial pain.25 A newer variation of gabapentin, pregabelin, may prove to be an even more effective agent. Currently, it is approved in the US for the treatment of neuropathic pain developing from postherpetic neuralgia or diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The mechanism of pain relief for tricyclic medications may be independent from their effect on depression. The positive effects seem to depend on two mechanisms: the blockade of norepinephrine uptake, and its antagonist action on the N-methyl D-aspartate receptor.8, 22, 27

Physical therapy

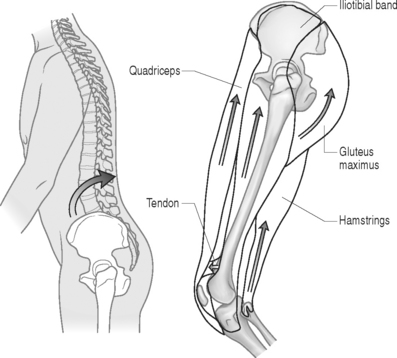

The initial step in prescribing a physical therapy program depends upon a detailed musculoskeletal assessment. Evaluation of biomechanical relationships is an integral part of this process. Patients who present with concomitant osteoarthritis of the lower extremities (hip, knee, ankle), causing restricted and painful joint range of motion (ROM), will require special consideration. Lower extremity flexibility should be assessed in all patients. Short hamstring and iliopsoas muscles may increase the stress on lumbar lordosis and the lumbopelvic motion relationship. Patients with significant restrictions may greatly benefit from physical therapeutic stretching. A kyphotic posture, adopted to reduce pincer effect of lordosis in spinal stenosis, will secondarily lead to shortening of the hip flexors (Fig. 99.6). Chronically shortened hip flexors will aggravate the condition by forcing the patient to effectively increase lordosis when attempting to stand erect.

Studies on low back pain suggest that strong secondary psychologic benefits are derived from positive self-efficacy concepts, and confrontational rather than avoidance behavioral strategies.9, 19, 32 These strategies are reinforced by the reasonable return to activity program and independent daily exercise program. The benefits of this positive health belief system may be more important than the physiologic counterpart of exercise. Despite this fact, many patients who do not tolerate the transition to exercise may receive benefit from limited passive treatments such as therapeutic modalities of heat, ultrasound, and soft tissue mobilization.

When a significant amelioration of painful symptoms occurs, a vigorous cardiovascular conditioning exercise program is typically introduced. While maintaining flexibility and some degree of trunk strength through a program of daily exercise seems to make sense, only fitness has been implied as preventive for lower back pain.1 Patients may be advised to partake in regular and slowly progressive amounts of safe aerobic exercise (exercise bicycle, swimming pool exercise). For cardiovascular conditioning, the authors have found that the upright stationary bicycle is well tolerated. Other patients with a more extensive history of back pain may perform better on recumbent bicycle. Patients are encouraged to increase their tolerance to treadmill in order to develop upright endurance. More functionally advanced patients may be able to use stair climbers or a stairmaster, but these activities present more obvious difficulties to many elderly patients whose balance and coordination may be affected or whom may have hip or knee osteoarthritis. Most patients will be able to exercise on the elliptical machines that build lower extremity endurance and balance without the same degree of axial impact loading.47 Many patients with lytic or degenerative spondylolisthesis of varying severity may be able to successfully return to most sport activities. High-grade spondylolisthesis should be a contraindication to participation in contact sports. Patients can be encouraged to perform exercise and noncontact sports to tolerance. Many can engage in running and tennis even after having experienced significant episodes of radiculopathy (Fig. 99.7).

The hypothetical rationale for assessment-based physical therapy requires an understanding of the pathoanatomic process associated with each type of spondylolisthesis. For example, in DSSS, a flexion-biased movement and exercise program is preferable. There are relatively few specific studies confirming the outcome effects of specific therapy.15,47

Sinaki et al.15 reported on the outcomes of 48 patients with symptomatic back pain secondary to spondylolisthesis treated conservatively for 3 years. They compared the outcomes of flexion-biased and extension back strengthening exercise programs. The patients were divided into two groups: those performing flexion, and those performing extension back strengthening exercises. Flexion exercise consisted of partial sit-ups, pelvic tilts, and chest-to-thigh exercises. Extension exercises consisted of upper back extension from the prone position and hip extension from the prone position. At 3 years, overall recovery rate was 62% for the flexion group and 0% for the extension group. O’Sullivan et al.47 prospectively compared the effect of a spine stabilization exercise program with non-specific exercise therapy in 44 patients with spondylolisthesis or spondylolysis. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of the two treatments. At 30 months, the stabilization exercise group experienced significant benefits while those in the non-specific exercise therapy group did not. While the majority of the patients, whose average age was 30 years, appeared to experience chronic low back pain it is unclear how the authors established that symptoms were specifically related to chronic IS.

Bracing

Bracing may play a role in early protection of a painful segment while the patient begins a comprehensive stabilization program. In addition to support of the area, both the warmth and proprioception48 gained by the brace may lead to patient comfort. Bracing may be the best option, particularly for debilitated patients when physical therapy would be either difficult or simply pose a health risk. The role of bracing has been studied most extensively in acute IS presenting in young or adolescent patients and is discussed in detail by Frank Lagatutta (see Ch. 129). There is little or no literature investigating the clinical effect of bracing in the conservative management of degenerative spondylolisthesis or spinal stenosis.49 Some authors have advocated a 4–6 week trial of brace management. We have found that soft or semirigid lumbar supportive braces are sufficient for patient comfort and ease of use. Braces will generally be tolerated better by thin than obese patients. Many patients with uncomplicated spondylolisthesis may find that a properly fit spinal orthotic provides comfort and pain relief. Bracing may be indispensable in patients suffering with spondylolisthesis complicated by additional spinal alignment and mechanical problems such as scoliosis, uncompensated scoliosis, lateral listhesis, or hyperlordosisis. The most important aspect of bracing is whether the patient will actually use the device. The authors’ experience is that patients rarely tolerate rigid bracing, whether custom made or the soft spinal variety. Since these orthotics are costly, a realistic appraisal of probable usage should be undertaken prior to providing a prescription for their purchase.

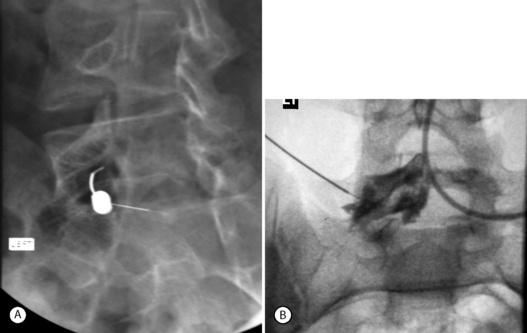

INTERVENTIONAL SPINE TECHNIQUES FOR SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

Rationale for use: hypothetical mechanisms

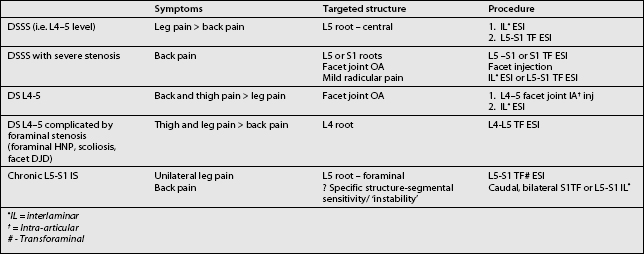

Incorporating spinal injection procedures into the rehabilitation program of patients with spondylolisthesis can be an effective tool. When other medical rehabilitation fails (e.g. physical therapy, oral medications) interventional treatment is well recognized as a potent therapeutic aide. As with the development of the medical rehabilitation component of treatment the anticipated success of an injection procedure will depend upon a careful clinical and radiographic assessment of the patient. Ultimately, this allows the spine clinician to determine which spinal structures are pertinent to symptomatic complaints, choosing a logical sequence of treatment interventions, and proper execution of what often are technically demanding procedures (Table 99.3). A detailed evaluation of this nature will maximize the potential benefit of this therapeutic modality. The extent to which it is used in specific clinical scenarios is a matter of greater controversy and the subject of ongoing investigations. Their effectiveness in maintaining reasonable outcomes in patients with more severe presentations of disease who are otherwise healthy candidates for surgery is one area of debate, whereas treatment is more widely supported for mild to moderate disease.24,50

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree