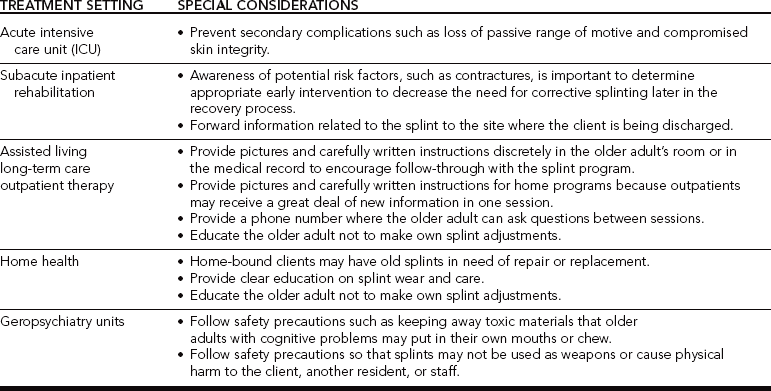

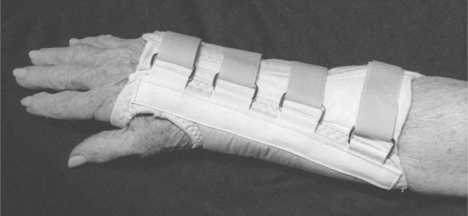

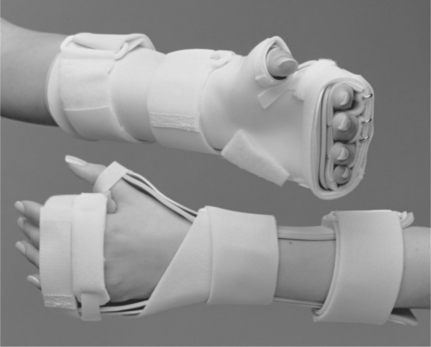

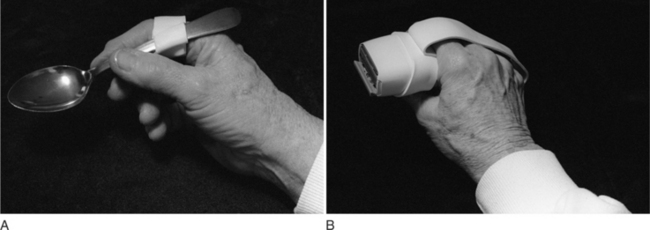

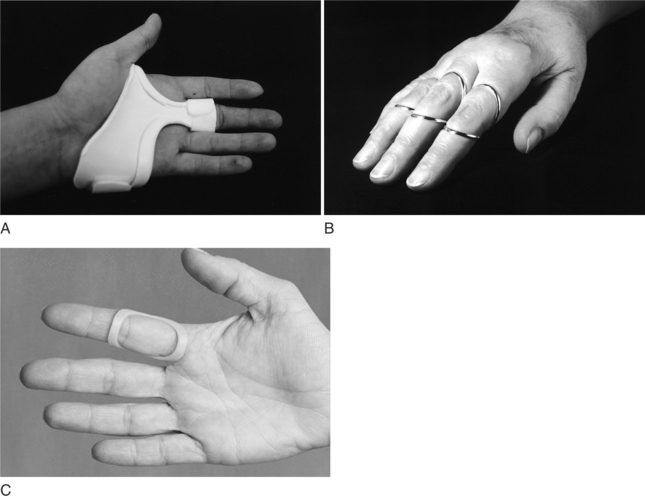

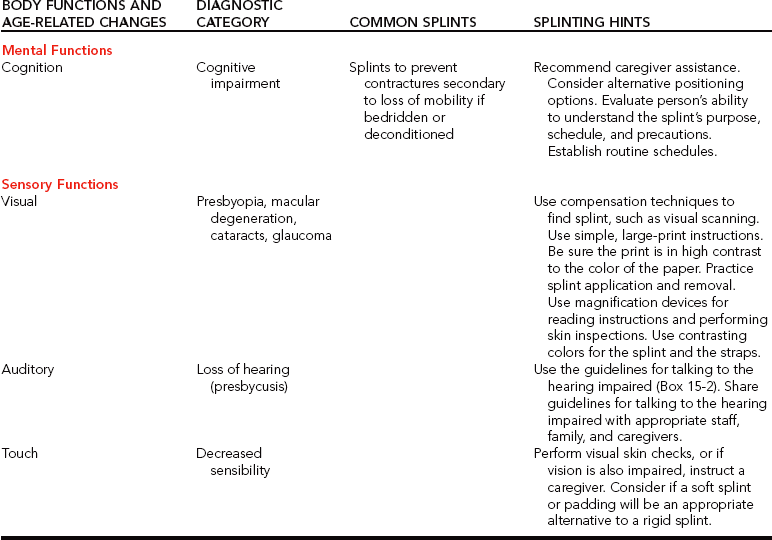

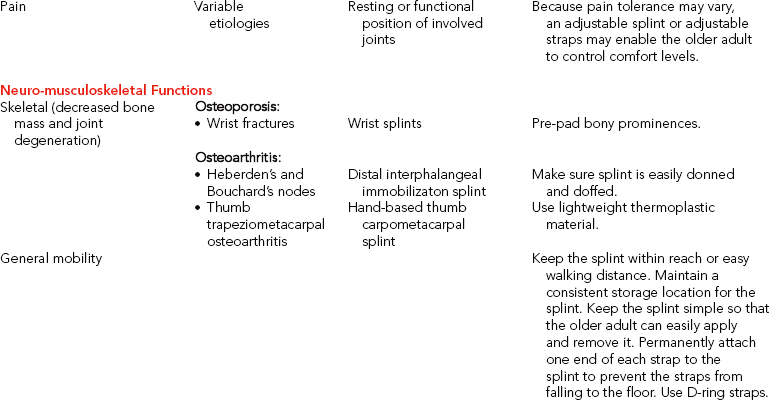

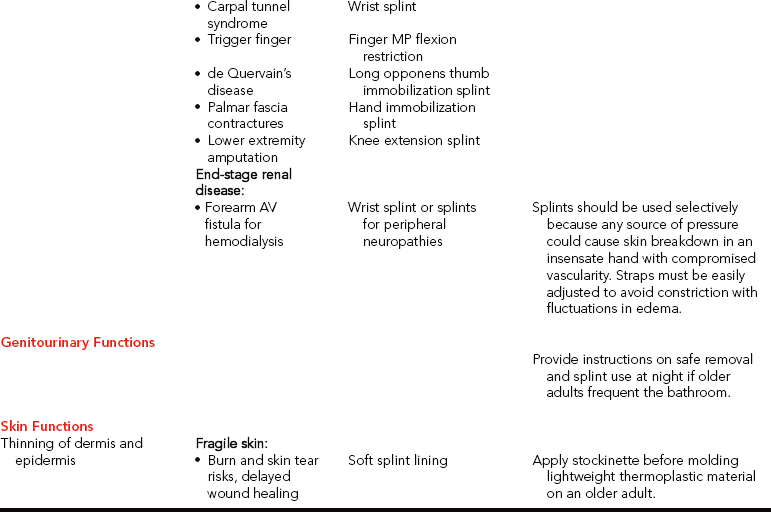

CHAPTER 15 1 Describe special considerations for splinting older adults in different treatment settings. 2 Identify age-related changes and medical conditions that may affect splint provision. 3 Explain how medication side effects may affect splint design and care instructions for older adults. 4 Recognize how an older adult’s occupational performance may influence splint use and design based on the following client factors: • Neuro-musculoskeletal functions: • Cardiovascular and hematological functions • Digestive, metabolic, and endocrine functions 5 Be familiar with a variety of prefabricated splint options and materials available to custom design splints. 6 Describe factors that influence methods of instruction for an older adult and caregiver. The age of 65 has been used as the marker in establishing policies for the older adult [Chop and Robnett 1999]. According to the Administration on Aging, by 2030 (when the baby boomer generation reaches 65) the older adult population will double and represent 20% of the total population [DHHS 2003]. Although most older adults live independently, approximately 4.5% reside in nursing home facilities (with the percentage increasing with time). Regardless of health status, 27.3% of community dwelling older adults and 93.3% of institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries have some limitation in function that prevents them from being fully independent in activities of daily living (ADL) [DHHS 2003]. Thus, approximately 7.2 million individuals aged 65 and older have chronic illnesses and disabilities that require supportive care for ADL [Binstock 2001]. Therapists often provide therapeutic interventions for older adults to improve functional status. Interventions include the design and fabrication of splints. Aging may affect hand dexterity [Lewis 2003], and older adults may benefit from splinting to improve occupational performance. Fundamental principles of evaluation, design, and fabrication of splints do not change as people age. Therapists do, however, need to be aware of special considerations necessary to accommodate unique needs of the older adult. When designing a splint for an older adult, the therapist should consider the special needs of the older adult, the goal of the splint, and the splinting supplies available. A splint for an older adult should (1) prevent undesirable motion while permitting normal motion, (2) provide adequate stability, (3) decrease energy expenditure when worn, (4) provide safe distribution of force, (5) be comfortable, (6) be applied and removed easily, (7) be economical, (8) be durable, (9) be easily modified [Good and Supan 1992], and (10) be easily cleaned. The older adult’s environment is also an important consideration for clinical decision making. Therapists treat older adults in multiple settings.Box 15-1 provides a summary of considerations for the design of splints for individuals in any treatment setting.Table 15-1 presents specific considerations for different settings. The older adult’s living situation (e.g., independence in a community versus dependence in a long-term care setting) is important when the therapist determines the most appropriate splint. For example, an 80-year-old woman with osteoarthritis who performs her own self-care and requires the use of her hands throughout the day may benefit from a thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) immobilization splint to improve her daily function. Table 15-2 provides a summary of age-related changes and medical conditions that affect the design and approach to splinting. The following client factors [AOTA 2002] are based on selected classifications from the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [WHO 2001] as they relate to considerations for splinting older adults. Table 15-2 Summary of Age-related Changes and Medical Conditions Impacting Splint Design or Provision If the older adult has significant cognitive impairments, the therapist recommends assistance. The therapist must educate any new caregiver about the splint’s purpose, wearing schedule, care, correct application, and possible problems. Individuals with later-stage dementias often posture in flexed positions and thus the caregiver may require recommendations to maintain skin integrity. If there are cognitive impairments, or if a caregiver is involved, the risks versus the benefits of a splint must be carefully weighed against alternative positioning (such as the use of pillows or dense foam wedges). In addition, the therapist may consider using D-ring straps for a person with dementia who is constantly trying to remove the splint. Of people over age 65, researchers found that 17.2% have some type of visual impairment related to developing functional limitations [Dunlop et al. 2002]. Decreased vision can also play a role in noncompliance of splint wear. For example, some older adults may be unable to apply their splints because of poor figure/ground discrimination. Older adults may also have difficulty seeing straps and Velcro as well as inspecting their skin. Using colored thermoplastic splinting material and contrasting colored straps may assist the older adult who has poor visual discrimination. Bright colors may prevent the splint from being easily lost or mistakenly sent to the laundry. For older adults who have macular degeneration (e.g., blurred or loss of central vision), the therapist encourages the use of compensatory techniques during application and removal of the splint and during skin inspections. Compensatory techniques include eye scanning, head turning, and placement of the splint or hand into the field of vision. Approximately 25% of older adults between 65 and 74 years of age, 50% of older adults age 75 or older, and 65% of those age 85 and older describe difficulty with hearing [American Federation for Aging Research 2004]. Hearing impairment influences verbal explanations and statements. Sometimes hearing problems can be detected during the initial interview or during splint fabrication. Therapists should not rely solely on printed information to relay instructions because some older adults may be unable to read or have visual impairments that make reading difficult or impossible. The therapist may need to use more tactile cues when positioning the person for splinting. When talking to a person who is hearing impaired, the therapist should use the guidelines outlined inBox 15-2. Somatosensory research has demonstrated a decline in two-point discrimination with age [Stevens and Patterson 1995]. Because the decline is gradual over the life span, older adults may not be aware of their diminished sensibility. Because vision is the primary sense used to compensate for decreased tactile sensation, when both sensory functions have declined the older adult is at greater risk for compromised skin integrity. Tactile sensation may become impaired secondary to poor positioning of older adults with limited mobility. Decreased sensation may contribute to compression neuropathies of the median or ulnar nerves. Cubital tunnel syndrome, a compression of the ulnar nerve at the elbow level, may result from constant pressure on flexed elbows while sitting in a wheelchair or from prolonged bed confinement. A well-padded elbow splint with the elbow flexed 30 to 60 degrees prevents further pressure to the nerve [Clark et al. 1998, Blackmore 2002]. Prefabricated soft elbow pads are another option. Compression of the median nerve at the wrist may be due to prolonged wrist flexion posturing or secondary to an associated medical condition, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) or diabetes. A prefabricated wrist splint with D-ring straps is easier to don and can be used to prevent nerve compression (Figure 15-1; and see Chapter 13 for further discussion of these conditions). One of the most impacted body systems affected by age is the skeletal system. Osteoporosis and osteoarthritis (OA) are common diagnoses that often require splinting as part of the intervention process. Osteoporosis is a gradual loss of bone density that begins as young as age 35 [Boughton 1999]. After menopause, the rate of bone loss for women increases [Barzel 2001], and the distal radius is especially vulnerable to fractures [Bostrom 2001]. A common fracture of the distal radius is called a Colles’ fracture, which often occurs because of accidental falls [Nordell et al. 2003]. Although wrist fractures are usually treated in an outpatient setting, older individuals may at the same time fall and sustain a hip fracture, which initially requires inpatient therapy. Sustaining a Colles’ fracture can be associated with functional declines in physical performance in hand strength and walking speed [Nordell et al. 2003]. A volar wrist splint is generally indicated after removal of an arm cast or external fixator for immobilization (see Chapter 7). As the fracture heals, the splint goal may change to one of mobilization (which can be achieved by serial adjustments to improve wrist extension). It is also important to determine if there are other etiologies causing upper extremity impairments. For example, a thorough evaluation for a client referred with a wrist injury may reveal preexisting sensory loss in the digits due to compression of cervical nerve roots caused by OA. The sensory loss might otherwise have only been associated with the wrist fracture. Another condition that affects the skeletal system is OA. Women are more frequently affected, and the initial onset typically occurs between ages 50 and 60 [Melvin 1989, Rozmaryn 1993, Hellman and Stone 2004]. Primary OA results from idiopathic or known causes. Secondary OA results from congenital joint abnormalities; genetics; infections; and metabolic, endocrine, or neurological disorders [Beers and Berkow 1999]. Most older adults have evidence of some cartilage damage [Bland et al. 2000]. Hand joints are more frequently affected by primary OA [Rozmaryn 1993, Bozentka 2002], which is characterized by enlarged distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (Heberden’s nodes) and enlarged proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints (Bouchard’s nodes). The nodes typically cause more discomfort in the index finger because of the demands placed on the joints during activities that require pinch. An immobilization splint for the DIP joint is a conservative measure to decrease pain (Figure 15-2). Surgical fusion may be warranted for more advanced cases. Figure 15-2 Enlarged DIP joints from osteoarthritis may become painful and benefit from immobilization to decrease pain. OA of the thumb at the CMC joint is another common reason for a splint referral. Initial conservative management usually requires a hand-based thumb immobilization splint (see Chapter 8). Individuals with this condition must be educated in joint protection techniques and instructed with methods to balance activities throughout the day to break the pain cycle. As discussed in Chapter 8, there are different approaches to splinting arthritic hands. The most prevalent approach is to fabricate a removable hand-based splint to immobilize only the CMC joint. Researchers evaluated the effectiveness of a short opponens splint (only the CMC is immobilized) compared to a long opponens splint (the wrist, CMC, and thumb metacarpophalangeal (MP) are immobilized). Researchers found that 42% of the subjects who wore the short opponens splint reported performance of ADL to be easier. Fifty-one percent of the subjects reported performance of ADL to be the same when wearing the short opponens splint. Some subjects (7%) found ADL performance more difficult while using the short opponens splint. Only 16% of subjects who wore the long splint found activities easier to perform [Weiss et al. 2000]. The researchers concluded that splinting is effective for pain reduction and helps to reduce subluxation in the early stages of OA. Chronic flexion of the thumb MP joint, or an adduction contracture, can lead to a hyperextended interphalangeal (IP) joint. This can be conservatively treated with a figure-of-eight splint to improve stability and function of the thumb (Figure 15-3). If the older adult needs to use a walker and has thumb pain or a weak grip, a prefabricated walker splint can be used to decrease stress to the thumb (Figure 15-4). Figure 15-3 A tri-point figure-of-eight design can stabilize the thumb IP joint to prevent hyperextension during pinch. Deformities that result from RA may be seen in older adults. However, the most common onset of this systemic condition is in women typically between the ages of 40 and 50 [Pincus 1996]. Mitt splints lined with Plastazote can be helpful for older adults who have residual painful deformities and fragile skin (Figure 15-5). Additional examples of splints for RA are included in the chapters on wrist, hand immobilization, thumb, and mobilization splints. Many older people become sedentary, which decreases aerobic capacity, muscle strength, ROM, and coordination [Lavizzo-Mourey et al. 1989, Evans 1999]. The therapist should be cautious that splints do not result in unnecessary immobility or loss of engagement in activity. Among persons over age 65 living in the community, 30% fall each year [Gillespie et al. 2004]. Associated injuries include lacerations and bruising; scalds and burns; arm, wrist, hand, and hip fractures; and concussions [Lavizzo-Mourey et al. 1989, Daleiden 1990, Potempa et al. 1990, Carter et al. 2000]. The percentage of falls in institutions is even higher [Gillespie et al. 2004]. The risk for falls increases with age, with one out of two older adults over age 80 experiencing a fall every year [Crane 2002]. If a splint is out of reach, the older adult may not be able to reapply it because of difficulty with ambulation and reach. Maintaining a consistent storage location within reach and easy walking distance is important. Progression of cardiovascular disorders may lead to a CVA resulting in abnormal tone on one side of the body. When making a splint for an older adult with abnormal tone, it may be important to also consider principles involved with splint design related to a coexisting condition such as OA of the thumb CMC joint. In addition, orthokinetic properties of materials should be cautiously selected because they may affect tone (see Chapter 14). Some neurologic conditions cause tremors. Tremors may be associated with Parkinson’s disease, idiopathic essential tremors, or tremors secondary to medication side effects. Splints may be used as a base to hold assistive devices to improve self-care function in the presence of tremors. An adaptation may be made to a splint that is required for a coexisting diagnosis. A splint may be made solely to position a self-care utensil, such as a spoon, or to stabilize a pen to write (Figure 15-6). Many older adults who receive therapy have cardiovascular disease, which may be the primary or secondary reason for referral. For someone who has cardiovascular disease, the therapist should educate the older adult to store the splint in close proximity in order to conserve energy. When fitting someone with a lower extremity splint, precautions for peripheral vascular disease should be observed. Another age-related change is a decreased small vessel supply [Saxon and Etten 1994, Bottomley and Lewis 2003]. The temperature of the splint material should be carefully checked, and a double layer of stockinette should be considered instead of applying warm splint material directly to the skin. Older adults who have less ability to dissipate heat are vulnerable to burn or torn skin. If older adults have decreased cognition and thin skin, they may not be aware of the potential for burns. Poor circulation also results in delayed wound healing after skin breakdown. Diabetes mellitus (DM), a disorder of the endocrine system, is a common secondary diagnosis affecting up to 15.1% of older adults [DHHS 2003]. There are two types of diabetes. Type 1 is insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), with onset before age 30. Type 2 is non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), with onset more typically after age 30 [Beers and Berkow 1999]. Individuals with long-standing diabetes have an increased incidence of other conditions that must be considered before a splint is made. Individuals with diabetes are at greater risk of associated conditions [Cagliero et al. 2002] that may require splints for the upper extremity [Chammas et al. 1995]. There is an increased incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in persons who are diabetic. Conservative management includes a wrist immobilization splint with the wrist positioned in neutral. This splint is worn at night. Stenosing tenosynovitis may occur at the first dorsal extensor compartment on the radial aspect of the wrist. This is called de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, which is managed with a thumb immobilization splint on the wrist and thumb (see Chapter 8). Trigger finger is another form of stenosing tenosynovitis that occurs during middle age and that has an increased incidence associated with diabetes. Conservative management may include a splint to restrict MP flexion [Fess et al. 2005] to decrease inflammation in the distal region of the palm near the involved digit. The therapist may decide to (1) custom fabricate a splint (Figure 15-7A), (2) take measurements for the purchase of a custom-manufactured silver ring splint (Figure 15-7B), or (3) order a prefabricated splint (Figure 15-7C). Considerations for this decision include the availability of materials, reimbursement source, and client input.

Splinting on Older Adults

Influence of Different Treatment Settings on Splint Design

Age-Related Changes, Medical Conditions, and Splint Provision

Mental Functions (Cognition)

Sensory Functions

Auditory System

Touch

Neuro-musculoskeletal Functions

Sammons-Preston Rolyan

General Mobility

Neurologic System

Cardiovascular and Hematologic Functions

Digestive, Metabolic, and Endocrine Functions

Endocrine System

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Splinting on Older Adults