Many different classification schemes exist for naming and differentiating soft tissue tumors, but the one most commonly used is that proposed by the World Health Organization (

12). It delineates 16 different histologic categories, each of which is subdivided into benign and malignant tumors. The name of each tumor is based on the histologic type of the predominant cell.

Table 92.1 is a chart that has been modified from the World Health Organization classification scheme with only the categories of soft tissue types applicable to the foot and ankle included.

Because the histologic classification of soft tissue tumors cannot be relied on for an accurate prediction of clinical course, grading and staging systems have been developed to assist in the prognostic and therapeutic aspects of tumor management. Many different authors have proposed such systems, which can be found specifically in more extensive oncologic texts. This section only serves as a brief overview.

GRADING

Grading is a measure of the degree of malignancy. The grade of malignancy is most often determined by the degree of cellularity, cellular anaplasia, mitotic activity, the amount of necrosis, and expansive or invasive growth (

13). Of these factors, the degree of mitotic figures and the extent of necrosis seem to be the most predictive (

1). The number of grades varies among systems from distinguishing between only high and low grades to four-grade differentiations.

STAGING

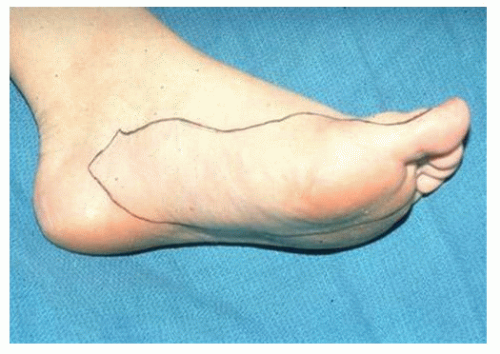

Staging of soft tissue tumors is a determination of the extent of the disease at the time of the initial histologic diagnosis. The stage is based on the size of the tumor, metastasis to local or regional lymph nodes or distant organs, and the anatomic location (intracompartmental or extracompartmental).

Currently, three systems exist for the staging of soft tissue sarcomas. The American Joint Committee on Cancer has published a staging system, the TNMG system (

Table 92.2) (

14). It uses the size and extension of the tumor (T), the involvement of lymph nodes (N), metastasis (M), and the grade (G) of the sarcoma. The system includes four stages, with stages I, II, III based on histologic grade and stage IV based on local or distant invasion. Another system, proposed by Enneking (

15), is used for both soft tissue and bone tumors (

Table 92.3). The three stages are based on surgical grade (G), surgical site (T), and metastasis (M). This system differs from the other two in that the tumor size is not taken into consideration. The last system, proposed by Hajdu (

16), has four stages based on the tumor size, the site (above or below the superficial fascia), and the histologic grade (

Table 92.4).

Currently, the appropriate method by which soft tissue sarcomas should be staged is debated. However, investigators agree that the appropriate treatment of a soft tissue sarcoma should be based on the stage of that tumor. Staging of soft tissue sarcomas requires a combined effort of the clinician, the oncologist, and the pathologist to provide the patient the best therapeutic approach.

Although the staging of benign lesions is not as important as that of malignant lesions, a staging system can still be helpful in the evaluation and management of a benign soft tissue mass. Enneking (

15) devised a staging system for benign soft tissue masses (

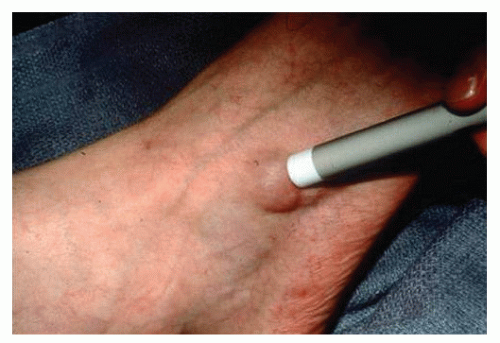

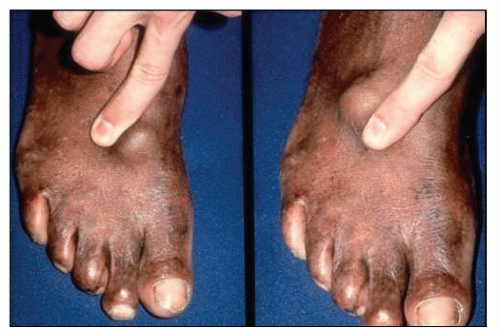

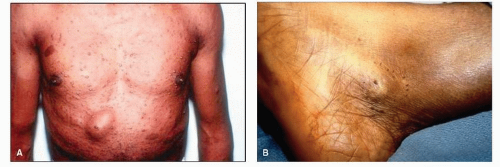

Table 92.5). Stage 1 (benign, latent) lesions have a benign histologic pattern, are intracapsular, and do not metastasize. They are freely movable, nontender, do not enlarge, and

sometimes regress over time. Stage 2 (benign, active) lesions are histologically benign, are intracapsular, and also do not metastasize. Although intracompartmental, these lesions may distort or compress natural barriers. They are often painful and actively enlarge. They are freely movable within the soft tissues. Stage 3 (benign, aggressive) lesions are histologically benign. They are sometimes extracapsular and can cross compartmental barriers. Usually, these masses are painful, rapidly growing, and fixed to the underlying tissues. Most important, these lesions may undergo malignant transformation.