CHAPTER 36 Skin care needs of the pediatric and neonatal patient

1. Define the terms infancy, neonate, premature, and micropreemie.

2. Identify skin, risk, and pain assessment tools designed for pediatric patients.

3. Discuss special considerations for neonatal skin care, including bathing and use of cleansers, antiseptics, and emollients.

4. List risk factors for skin breakdown in pediatric patients.

5. Describe common pediatric skin conditions and age-specific interventions.

6. Identify wound care products that can be used for pediatric patients.

PART I: THE PEDIATRIC PATIENT

Infants and children experience alterations in skin integrity related to congenital conditions, poor nutrition, severe illnesses, surgical procedures, and trauma. Box 36-1 lists factors and conditions that place the pediatric patient at risk for skin breakdown. Infants and children born with congenital anomalies often require surgical intervention. Children with anorectal or urinary tract malformations may need a colostomy, ileostomy, or urostomy, any of which places them at risk for developing peristomal skin issues. Children with swallowing difficulties and those with significant caloric needs that cannot be met with oral feedings alone require a gastrostomy tube, another potential source of skin breakdown. Incontinence-associated dermatitis (i.e., diaper rash) is a common problem in children after closure of an ostomy and in children who have diarrhea associated with short bowel syndrome or cancer treatments. Additionally, although more common in adults, pressure ulcers can develop in children. The wound care nurse plays an essential role in the management of children and can significantly impact the child’s experience by minimizing the frequency of dressing changes with the use of advanced wound care products and by reducing the use of adhesives with creative methods of securing dressings. Although children vary significantly in size, the availability of a large number of dressings or multiple sizes of products is not necessary. A few key products can fulfill all requirements because most dressings can be cut to fit the needs of the pediatric patient.

BOX 36-1 Risk Factors for Pediatric Skin Breakdown

• Neurologic deficits (affect mobility, ability to sense pain and communicate pain)

• Changes in height and weight with growth (may develop new pressure points with medical equipment such as wheelchairs and orthotic devices)

• Medications that alter body’s ability to heal or increase likelihood of skin breakdown (chemotherapeutic agents, immunosuppressive medications)

• Alterations in nutrition, particularly feeding disorders requiring gastrostomy tube

• Factors that impair perfusion (edema, vasopressors)

• Medical equipment that limits position and mobility (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, dialysis catheters)

• Medical devices that require adhesives to secure or that can cause pressure (endotracheal, nasogastric, vascular access tubes; bilevel positive airway pressure masks; monitoring equipment; electrodes)

• Prolonged hospitalization in intensive care unit

• Frequent or prolonged exposure to urine and/or stool

• Congenital anomalies requiring surgery

Common pediatric conditions

Anorectal malformation is a term used to describe the failure of the rectum to migrate in utero to connect with the anus. It includes a spectrum of congenital anomalies of the rectum and urinary and reproductive structures that vary significantly in complexity. Boys often have a rectourinary fistula, which is an abnormal communication between the rectum and the urinary tract. Girls generally have a fistula to the genitalia or perineum. A persistent cloaca is a more serious form of imperforate anus in girls that involves the fusion of the rectum, vagina, and urinary tract into a single common channel. The channel exits through one orifice located at the normal urethral site. Corrective surgery is necessary for all of these malformations. The operations are often staged, with the first stage being creating an ostomy (O’Connor Guardino, 2007).

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a skin condition involving various defects in the epidermal basement membrane. Manifestations include blisters and erosion in the skin and may affect the mucous membranes. EB precipitates significant caloric needs. Because children may have difficulty with oral intake due to oral lesions and esophageal strictures, a feeding tube may be necessary. Children with EB are often managed by physicians and nurses who specialize in their care. EB is described in greater detail in Chapter 30.

Burns, specifically scald and contact burns, most commonly occur in infants and toddlers. Toddlers are at high risk for sustaining burns as they begin to walk and grab onto tables, tablecloths, and radiators to pull themselves up to a standing position. Hot liquids pulled down from tables result in burns to the head, face, and chest. Radiator-type heaters are exposed in many homes and may be extremely hot, resulting in palm burns to infants as they begin exploring their environment. Hot water tanks set higher than 120°F put children at risk during bathing. Burns in children may also be associated with child abuse or neglect. The epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management of burns are discussed in detail in Chapter 32.

Obesity presents potential problems such as pressure ulcers, delayed wound healing, and wound dehiscence. Based on expert committee recommendations (Institute of Medicine and American Academy of Pediatrics), children with a body mass index percentile for age and sex in the 95th percentile or higher are considered obese (Chen and Escarce, 2010). As in the general population, the frequency of obesity in children has increased dramatically; the overall prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents aged 2-19 increased from 5.5% in 1980 to 16.9% in 2008 (Ogden and Carroll, 2010). The 2007 to 2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported that 10.4% of 2- to 5-year-olds, 19.6% of 6- to 11-year-olds, and 18.1% of 12- to 19-year-olds were obese (Ogden and Carroll, 2010). The pathophysiology, prevention, and management of obesity-related skin problems are discussed in Chapter 35.

Topical wound management: dressings and dressing changes

Chapters 16 to 18 provide details on wound bed preparation and the principles of wound management, principles that guide the care of wounds in patients of any age. Considerations specific to the needs of children are addressed in this chapter.

Minimize dressing change frequency

Dressing changes often are painful, and the experience can be quite traumatic for a child. Children endure many painful experiences during an illness or injury that cannot be mitigated. However, nurses can alter the pain experienced during dressing changes by choosing advanced wound care products that reduce the frequency of dressing changes and by selecting methods of securing dressings that eliminate or limit the use of adhesive tape. Box 36-2 lists a summary of issues to consider when selecting and securing dressings for pediatric use.

BOX 36-2 Considerations when Selecting and Securing Dressings for Pediatric Use

• Choose products that will minimize the number of dressing changes.

• Eliminate or limit the use of tape.

• Use gauze wraps, elastic wraps, or flexible tube net dressing to secure dressings.

• Limit the use of adhesive removers; clean off skin after use.

• Use antibiotic ointments selectively and cautiously.

• Work with home care companies to carry the products you use in your practice.

• Know the number of dressings allowed per month by insurance carriers.

• Unless you are absolutely certain that the wound will heal in less than 1 month, order supplies for the entire month because some suppliers will ship only once every 30 days.

Although some colleagues will not appreciate the advantage of high-tech dressings over gauze for wound healing, most can be convinced of the advantage, to everyone involved, of minimizing the frequency of dressing changes. Alginates and fiber gel-forming dressings are safe and effective for wound care in children and significantly decrease the number of dressing changes. Decreasing the frequency of dressing changes from three times per day to once per day or every other day by using a hydrofiber instead of gauze reduces the stress on the child, parents, and staff. When dressings must be changed more often than once per day, dressings should be secured with wraps or flexible tube netting to reduce stress, pain, and the time associated with tape removal (Clinical Example 36-1).

CLINICAL EXAMPLE 36-1

Outcome:

• Length of time between dressing changes increased from every 15 minutes to every 3 hours. Flexible net dressing conformed nicely to infant’s abdomen and required little effort to move out of the way during dressing changes. Only the foam was changed every 3 hours and was weighed to document output. Within 48 hours, dressing changes were decreased to every 6 hours.

Hydrocolloid dressings can be used to frame a wound that requires frequent dressing changes. By positioning hydrocolloid strips on two or all four sides of the wound, tape can be attached to the hydrocolloid and crossed over the dressing. During dressing changes the hydrocolloid is left in place; the hydrocolloid framing the wound changed every 4 to 5 days as it loosens (Clinical Example 36-2).

CLINICAL EXAMPLE 36-2

Objective:

• Twelve lesions of various sizes and at various stages of healing are present on his back, buttocks, and legs.

• Some wounds were covered with a hydrocolloid; deeper wounds were packed with a hydrofiber, then covered with gauze and tape.

• The child began to cry as soon as he was approached for assessment.

Plan:

• Hydrocolloid to dry wounds; change every 5 days.

• Hydrofiber covered with gauze, secured with transparent film dressing applied to deeper wounds on legs and buttocks.

• Change every 2–3 days, more frequently only when gauze saturated.

• Instruct mother on correct technique for removing transparent film dressing that minimizes pain.

Limit or eliminate use of adhesives

The method chosen to secure the dressing is extremely important. Children do not like having tape removed. Because skin irritation and tears can occur even when paper tape is used, dressings should be secured with gauze wraps, elastic wraps, self-adhesive wraps, or flexible tube net dressing whenever possible. Two- and three-inch wide conforming gauze is more effective than bulky loose weave gauze (e.g., Kerlix) on the extremities of smaller children. The conforming gauze can be taped to itself, thereby avoiding use of tape on the skin. Flexible tube net can be used to secure a dressing on the extremities of active children. It also performs well around the abdomen or chest of an infant or child to hold abdominal dressings, gastrostomy tubes, and central lines (Clinical Example 36-3).

Flexible net dressings need to be cut long enough to be effective; as they stretch, they decrease in length, roll, and fail to conform to the abdomen. For example, the distance on an infant’s abdomen from below the nipples to several inches below the gastrostomy is about 4 to 6 inches. However, once stretched over the abdomen, a 4- to 6-inch piece will become 3 to 4 inches and will not cover the area adequately to secure the dressing. Flexible net dressing should be cut twice the length needed, so for this infant 8 to 10 inches is needed (Figure 36-1).

Securing dressings in the burned child is particularly challenging because of the burn location and because children are so active. Toddlers are at high risk for sustaining burns to their chest, arms, face, hands, and abdomen as they begin exploring their environment. Burns to the hand are common, especially in cold climates and in homes with radiator heat. Toddlers need their hands to explore and are frustrated when their hands are wrapped. Application of a dressing that they cannot remove is challenging. Unaffected thumbs should be kept out of the dressing whenever possible. Gauze can be wrapped around the wrist to prevent the child from pulling off the dressing. Flexible tube net dressing or socks over the hand will help keep the dressing in place. Flexible net dressing is also useful for securing dressings on an extremity, the abdomen, and the chest. Although self-adhering wraps take more time to apply and remove, they are quite difficult for children to remove and therefore are very effective when the dressing does not need to be changed frequently (Clinical Example 36-3).

Prevent/treat wound infections

The skin provides a physical barrier to the invasion of microorganisms. This physical barrier is compromised by surgery, trauma, percutaneous tubes, and chronic wounds. The first line of defense against bacterial invasion, infection, and antimicrobial resistance is to keep the wound clean and covered. Most small cuts, surgical incisions on healthy children, and gastrostomy tube sites require no more than routine washing and a cover dressing. Topical antibiotic ointments should not be used routinely because indiscriminate use of topical and systemic antibiotics contributes to the growth of antibiotic-resistant organisms and use of topical antibiotics can lead to delayed hypersensitivity reactions, superinfections, resistance, and contact allergies (White et al, 2006). Specifically, mupirocin or polymyxin may promote the growth of gram-negative bacteria, and polymyxin has an unacceptably high rate of contact sensitization (Darmstadt and Dinulos, 2000). Therefore, topical antibiotic ointments should be used sparingly or not at all on wounds that have limited risk for becoming infected. Topical antibiotics are not an appropriate treatment option for colonized or infected wounds. Systemic antibiotics are warranted when bacterial infection or cellulitis is present.

Silver-based antimicrobial dressings can be used to inhibit bacterial growth and progression of bacterial penetration. As described in Chapter 16, silver binds to proteins in the cell wall (resulting in rupture of the wall), to bacterial enzymes and proteins (preventing them from performing their function and leading to cell death), and to bacterial cell DNA (interfering with cell division and preventing replication). This ability to bind to multiple sites results in an antimicrobial effect on a wide variety of microorganisms, including aerobic, anaerobic, gram-negative, and gram-positive bacteria, yeast, filamentous fungi, and viruses. This explains why resistance to silver is a rare occurrence (Ovington, 2004; Tomaselli, 2006). Silver is effective for treatment of mild wound infections. It is not indicted for cellulitis because it is effective only on superficial pathogens and not on those that have penetrated into the wound bed (Tomaselli, 2006). A variety of wound care products containing silver are available. Because some silver dressings cannot be mixed with normal saline, the wound should be cleaned with water and, if indicated, the dressing moistened with water. Evidence showing that silver dressings have no negative systemic or local effects is limited. Therefore, silver dressing should be used judiciously, for 2 to 4 weeks, until more research is available (Clinical Example 36-4) (Stotts, 2007).

Control pain

Large pieces of dressings are often aggressively packed in a wound, particularly after an incision and drainage of an abscess is performed in the emergency room or operating room. Removal of the packing when the child is awake is challenging. Packing often dries out and becomes adherent to the wound surface. Wetting the dressing before removing it will decrease discomfort. Wound packing is not well tolerated by children, is difficult for parents to do, and is generally not necessary. A dressing tucked in just far enough to keep the skin edges open and allow the wound to drain often is sufficient. A cotton-tipped applicator is helpful for gently tucking the dressing in the wound.

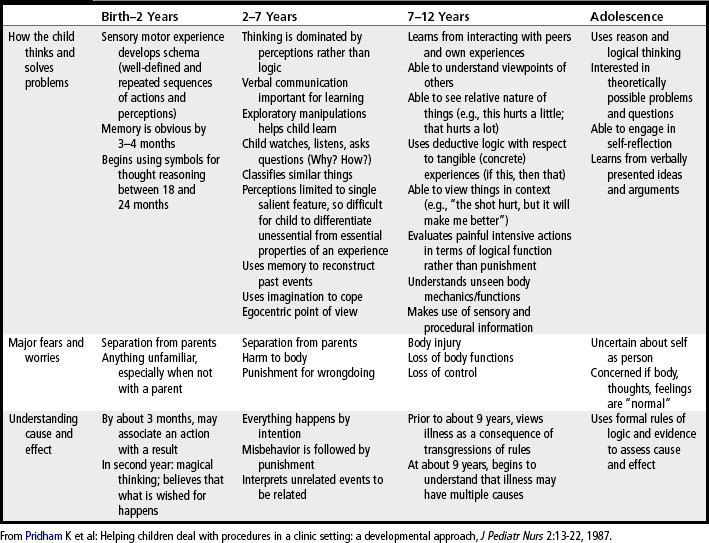

ELMA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics) and cream for topical anesthesia can be used safely on neonates and children prior to painful procedures. The use of EMLA in premature infants of gestational age less than 37 weeks needs further study (Lillieborg, 2004). Features of development such as how a child of a particular age thinks, what they fear, and how they learn are pertinent to helping children cope with procedures like dressing changes (Table 36-1).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree