CHAPTER 35 Skin care needs of the obese patient

Sixty-seven percent of Americans are overweight, more than one third of all Americans are obese, and 3% to 10% (at least eight million) are morbidly obese (Anaya and Dellinger, 2006; Ogden et al, 2007). Morbid obesity, once a rare occurrence in America, has essentially quadrupled since the 1980s (Camden, 2009). Studies suggest a substantial increase in obesity among all age, ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups (Lanz et al, 1998). In the early 1960s, only one fourth of Americans were overweight; today more than two thirds of U.S. adults are overweight, as are 25% of U.S. children. Worldwide, the number of individuals who are overweight or obese, which totals nearly two billion, now exceeds the number of those suffering from starvation (Aronne and Isoldi, 2008; Barrios and Jones, 2007).

Obesity has an economic, physical, and emotional impact on our patients. Americans spend close to $117 billion on obesity-related health problems, and $33 billion is spent annually in attempts to control or lose weight. Despite efforts at weight loss, Americans continue to gain weight, with obesity reaching epidemic proportions. Obesity is a factor in 5 of the 10 leading causes of death (Knudsen and Gallagher, 2003) and is considered the second most common cause of preventable death in the United States (Fox, 1995). In addition to the physiologic costs, some authors argue that obesity is associated with emotional conditions such as situational depression, altered self-esteem, and social isolation (Charles, 1987). However, others argue that society’s response to the obese person (i.e., prejudice and discrimination) leads to these emotional conditions (Gallagher et al, 2004).

Major comorbidities associated with obesity include type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, sleep apnea or obesity hypoventilation syndrome, and lipid disorders, including the metabolic syndrome. Other associated conditions include malnutrition, immobility, and depression. These comorbidities affect the morbidly obese patient disproportionately, and at a younger age. Diagnosis in the obese patient is difficult and procedures are technically more complicated, which ultimately places the obese patient at a disadvantage (Kral et al, 2000). In addition, many hospitals, clinics, and home care settings are not prepared to meet the needs of the obese patient group because of inadequate equipment and insufficient personnel to accommodate the needs of the larger patient, factors known to contribute to the patient’s risk of mechanical skin damage due to pressure, shear, or taping. However, advances in information, intervention, equipment, and education have helped reduce some of these risks (Gallagher et al, 2004).

Defining obesity

Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or greater; morbid obesity is defined as BMI greater than 40 (Box 35-1). Bariatrics is a term derived from the Greek word baros and refers to the practice of health care relating to the treatment of obesity and associated conditions. The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (2001) defines obesity as a lifelong, progressive, life-threatening, genetically related, multifactorial disease of excess fat storage with multiple comorbidities. Others describe obesity simply as the excessive accumulation of body fat, which manifests as slow, steady, progressive increase in body weight. However, recent discoveries suggest that obesity is more than simply overeating or lack of control. Genetics, gender, physiology, biochemistry, neuroscience, and cultural, environmental, and psychosocial factors influence weight and its regulation (Ludwig and Pollack, 2009). The National Institutes of Health regards obesity simply as a diagnostic category that represents a complex and multifactorial disease (Kuczmarski et al, 1994). However, obesity is most recently viewed as a chronic, multifactorial condition.

BOX 35-1 Body Mass Index Categories

Source: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, Md.

| Underweight | <18.5 |

| Normal weight | 18.5–24.9 |

| Overweight | 25–29.9 |

| Obesity | ≥30 |

Misunderstandings about the etiologies of obesity are common among health care providers. For example, obesity has long been perceived as a problem of self-discipline. Such misunderstandings can fuel prejudice and discrimination. In a culture that worships thinness, obese patients experience discrimination in schools, the workplace, and health care settings (Puhl & Heuer, 2009). As early as 1997, health care clinicians were often noted as biased against the larger patient (Thone, 1997).

Prejudice and discrimination pose barriers to care regardless of practice setting or professional discipline. The overwhelming misunderstanding of obesity likely interferes with preplanning efforts, access to services, and resource allocation. This misunderstanding is not universal but is pervasive enough to pose obstacles, and clinicians interested in making changes will need to recognize these barriers (Camden et al, 2008).

Altered skin function

In the obese person, a greater percentage of centralized and cutaneous adiposity is responsible for a number of changes in skin physiology and comorbidities that directly affect the skin. For example, the obese individual must perspire more efficiently when overheated in order to cool the body adequately due to the difference in the weight to skin ratio of the obese. Thus, the skin barrier function of the skin is altered to have increased transepidermal water loss than in skin with less adiposity. Dry skin is characteristic of obesity as a consequence of a fundamentally altered epidermal barrier. Levels of androgens, insulin, growth hormone, and insulin-like growth factors frequently are elevated, triggering sebaceous gland activity, altered skin pH, and an increased prevalence of inflammatory or noninflammatory papules, pustules, nodules, or cystonodules over the head, face, neck, back, or arms (Pokorny, 2008).

Unique needs

Common problems associated with the obese patient that interfere, at least potentially, with skin integrity include pressure ulcers, intertrigo, incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD), and foot dysfunction. Risk factors, manifestations, and prevention and management are described in Chapters 5, 7, 14, and 15 however, unique aspects occur in the obese patient population.

Pressure management

Pressure ulcers typically occur over a bony prominence and develop because of the inability to adequately offload the pressure; this is particularly true among very heavy patients. To compound this problem, friction and pressure can exist in locations unique to the obese person (Pokorny, 2008). Atypical or unusual pressure ulcers can result from tubes or catheters, an ill-fitting chair or wheelchair, or pressure within skin folds or over a point of contact not typically observed among nonobese patients (Camden, 2008).

Tubes and catheters can burrow into skin folds and ulcerate the skin surface. Pressure from side rails and armrests not designed to accommodate a larger person can cause pressure ulcers on the patient’s hips. Patients often develop pressure injury over the buttocks rather than over the sacrum, an area that frequently is the point of maximum contact with the surface because of the obese patient’s atypical body configuration. Shearing/pressure damage can develop lateral to the gluteal cleft over the fleshy part of the buttocks due to insufficient repositioning or transfer onto a stretcher or the operating room table. Interventions to prevent these types of mechanical injuries are listed in Table 35-1.

TABLE 35-1 Prevention of Unique Features of Skin Damage in the Obese Patient

| Causative Factor | Unique Feature in Obese Patient | Prevention Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure | Tubes and catheters burrow into skin folds | Reposition tubes and catheters every 2 hours Place tubes so that patient does not rest on them Use tube and catheter holders |

| Pressure between skin folds or under large breasts | Reposition large abdominal panniculus every 2 hours to prevent pressure injury beneath panniculus Physically reposition pannus off suprapubic area every 2 hours Use side-lying position with pannus lifted away from underlying skin surface, allowing air flow to regions Reposition breasts every 2 hours | |

| Pressure ulcer on hips or lateral thighs from side rails and armrests | Use properly sized bariatric equipment | |

| Pressure injury occurs in slightly lateral fleshy areas of the buttocks rather than midline (directly over the sacrum) because it is difficult to prevent excess skin on buttocks from being folded and compressed when repositioning the patient. | Bariatric support surface Proper repositioning Trapeze Establish, communicate, and implement safest transfer and positioning method to prevent shear that can be used during handoffs. | |

| Moisture-associated skin damage (e.g., intertrigo) | Excess perspiration to more efficiently cool the body when overheated Redundant skin creating skin folds Severe pruritus, burning, local pain between skin folds | Use cotton clothing (particularly undergarments) Maintain weight Avoid tight clothing Avoid corticosteroids and antibiotics Burrow solution (aluminum acetate) soak applied for 15–20 minutes twice per day to soothe and dry affected area |

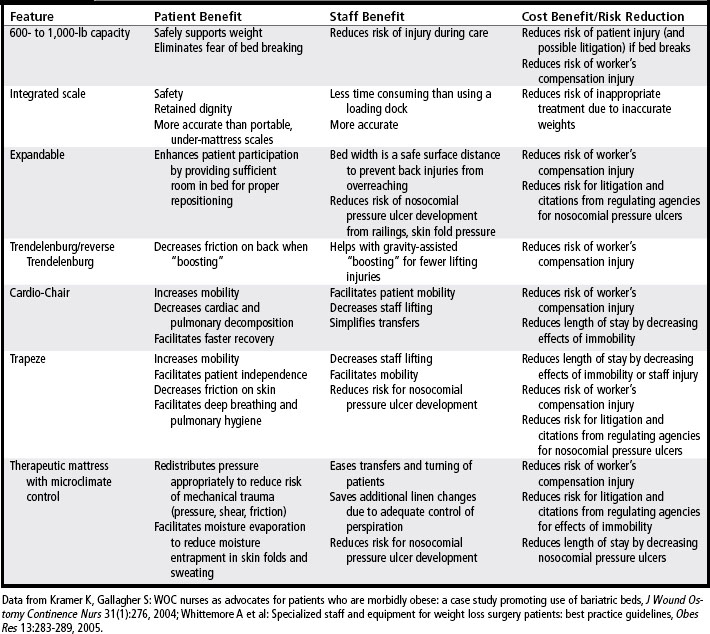

Bariatric beds with a pressure redistribution mattress will reduce the risk of pressure ulcers, promote patient independence, improve clinical outcomes, decrease staff workload, and help control unnecessary costs (Mathison, 2003). As described in Chapter 9, bariatric support surfaces are available in foam, air, gel, and water. They offer features with or without microclimate and moisture control that include low-friction covers. These devices are extremely useful for reducing friction and shear as well as dissipating moisture. In addition to benefiting the patient, bariatric beds provide specific features that impact on the staff and facility as listed in Table 35-2 (Kramer and Gallagher, 2004). The support surface with lateral rotation therapy, often regarded as the standard of care for certain pulmonary situations, can ensure sufficient repositioning for a very large patient whose need for frequent turning may otherwise pose a realistic challenge (Camden, 2008). Despite the value of rotation therapy in the prevention and treatment of skin injury among obese patients, additional precautions to prevent friction and shear are well advised. The patient should be fitted to the appropriately sized surface with correct pressure settings, and frequent assessments for skin changes must be implemented (Gallagher, 2002). For a listing of various bariatric surfaces, see Table 9-1.

Skin fold management

Moisture-associated skin damage, pressure, and intertrigo can develop between skin folds of the obese patient. Common sites include the inner thighs, axilla, underside of breasts, and panniculus. Pressure from the weight of the pannus over the suprapubic area or breasts against the chest wall and upper abdomen are sufficient to cause skin breakdown (see Color Plate 68).

Knowing the obese patient is at risk for moisture-associated skin damage and intertrigo, preventive interventions should be implemented upon admission. In addition to the interventions presented in Box 5-4, prevention strategies unique to the obese patient are presented in Table 35-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree