Abstract

Introduction

Cardiac rehabilitation programs are well recognized as being essential to the comprehensive care of patients with cardiovascular disease and chronic heart failure. These programs aim at reducing cardiovascular risks, promoting healthy lifestyle behaviours and compliance as well as limiting disability and increasing quality of life (QoL) of cardiac patients.

Purpose

To evaluate the impact of a 4-week cardiac rehabilitation program on physical parameters and several aspects of the QoL of cardiac patients.

Methods

A cohort of 101 cardiac patients (men: 70%) mean age 65 ± 12 years (mean ± SD) participated in a cardiac rehabilitation program. Before and after the 4-week cardiac rehabilitation program, the study recorded and assessed the patients’ physical parameters such as weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference and effort tolerance as well as QoL using different questionnaires: SF-36 Health Survey (SF-36), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI).

Results

The patients’ physical parameters (BMI and waist circumference) decreased by 3%, while effort tolerance increased by 25% ( P < 0.0001). Furthermore, for all patients, the PSQI, HAD and physical and mental SF-36 scores improved significantly ( P < 0.0001). The different SF-36 subscales’ scores did also increase after the program ( P < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Despite a modest weight loss and reduction in waist circumference, a 4-week cardiac rehabilitation program (short-term) seems to be sufficient for improving patients’ physical state and mental well-being.

Résumé

Introduction

Il est bien établi que les programmes de réadaptation cardiaque visent à réduire les risques cardiovasculaires, à favoriser des comportements sains et à les respecter, à réduire l’invalidité, et à améliorer la qualité de vie chez les patients cardiaques.

Objectif

Évaluer l’impact d’un programme de réadaptation de quatre semaines sur la qualité de vie des patients cardiaques.

Méthodes

Cent un patients cardiaques (70 hommes) âgés de 65 ± 12 ans (moyenne ± SD) ont participé au programme de réadaptation cardiaque. Certains paramètres anthropométriques tels que le poids et l’indice de masse corporelle (IMC), le tour de taille, ainsi que la tolérance à l’effort et la qualité de vie estimée à l’aide de différents questionnaires (SF-36, IQSP, HAD) ont été évaluées avant et après le programme de réadaptation cardiaque.

Résultats

Les paramètres anthropométriques (IMC et tour de taille) ont significativement diminué, accompagné d’une augmentation de 25 % de la tolérance à l’effort ( p < 0,0001). La qualité du sommeil, les scores de santé physique et mentale (SF-36) ainsi que les sous-échelles correspondantes se sont améliorés de façon significative chez tous les patients ( p < 0,0001). Par ailleurs, l’anxiété et de la dépression ont également diminué ( p < 0,0001).

Conclusion

En dépit d’une modeste réduction du poids et du tour de taille, un programme de réadaptation cardiaque de quatre semaines (court-terme) semble donc induire une amélioration du bien-être physique et mental.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation programs have largely demonstrated their efficacy in reducing complications for cardiac patients . Improved lipid parameters, blood pressure numbers, weight loss, diabetes prevention, patients’ well-being and increasing the rate of patients who stop smoking can explain the positive results. All these elements are also associated to an improved exercise tolerance, an independent prognostic value of morbi-mortality . Even if cardiac rehabilitation in specialized centres is still under-prescribed in France, this time period is crucial for providing patients with psychological comprehensive care in order to offer them an adapted and individualized support. The INTERHEART study reported that stress was associated to an increased risk of myocardial infarction (MI) . Furthermore, slight and moderate depressions seemed to affect a great number of patients after MI and their psychological profile was shown to be an independent mortality/complications risk factor at their 1-year follow-up .

If the positive impact of cardiac rehabilitation on metabolic profile and exercise tolerance is well documented in the literature , very few studies evaluated the impact of these rehabilitation programs on some dimensions of quality of life, especially after coronary revascularisation surgery , and it is difficult to come to a conclusion due to the heterogeneity of the studies on cardiac patients .

Belardinelli et al., followed by the HF-Action study (2009), showed that the quality of life of cardiac patients improved with exercise in the framework of moderate and long-term outpatient rehabilitation care . Furthermore, Stahle et al. validated the efficacy of a rehabilitation program comprised of exercise alone (1-year program) on quality of life improvements evaluated with the Karolinska questionnaire in older cardiac patients . Recently, Yohannes et al. reported that six weeks of cardiac rehabilitation training improved QoL, as shown with the SF-36 questionnaire, as well as anxiety and depression shown on the HAD scale and that these benefits were maintained at 12 months post rehabilitation . Nevertheless, to date, no study has documented, in cardiac inpatients in a rehabilitation centre, the short-term effects of a cardiac rehabilitation program on some QoL criteria including the different physical and mental health components (evaluated by the SF-36 questionnaire), quality of sleep, and their correlation to physical parameters.

The main objective of this study was to determine if a short and intense 4-week cardiac rehabilitation program could yield a positive impact on different quality of life parameters such as anxiety, depression, and quality of sleep as well as physical and mental health. The secondary objective was to verify if there was a correlation between the improvement of some physical parameters, exercise tolerance and quality of life.

1.2

Methods

1.2.1

Population

The patients were recruited at the Clinique Saint-Orens. The protocol was proposed to all patients referred for an inpatient cardiac rehabilitation program after an acute event (surgery, technical gesture or acute decompensated heart failure). Exclusion criteria were: unstable angina, pacemaker, uncontrolled hypertension, severe arrhythmia or any other neuro-orthopedic pathology that could have a major impact on exercise capacity. All patients gave their written informed consent to participate in this protocol that was revised and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Clinique Saint-Orens.

1.2.2

Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation program

This program focused on optimising the medical treatment, controlling cardiovascular risk factors, exercise training, gymnastics, diet monitoring, therapeutic education sessions and psychological support for some patients.

The exercise program lasted 3 hours per day, 5.5 days per week. The daily activity training included:

- •

a 45-minute exercise training activity on an ergocycle or treadmill and;

- •

a 1-hour walking session outside, at the target heart rate (HR) determined during the stress test, i.e. 60 to 80% of the heart rate reserve (HRR) .

The rate of perceived exertion was measured from 6 to 20 using the Borg scale . Furthermore, the patients participated in fitness, gymnastics, relaxation, Qi Gong or aquatic training sessions. The duration of these activities was set at 45 minutes (warming up and cooling down periods included). Each session was monitored by a physiotherapist or kinesiologist and supervised by a cardiologist. In addition to the exercise protocol, the patients were involved in therapeutic education sessions conducted by a multidisciplinary team with workshops and conferences on cardiovascular risk factors and treatment knowledge (≈ 3–4 hours a week).

1.2.3

Measures

Measures were recorded twice, the day after admission (PRE) and the eve before hospital discharge (POST). Each patient was taught how to fill out the questionnaires twice during their hospital stay. The questionnaires were handed out to the patients directly in their room and they filled them out alone. If patients had some questions regarding the questionnaires, they could ask the kinesiologist for more information.

1.2.3.1

Quality of life

Health-related quality of life was measured using the French version of the Short-Form (SF-36) Health Survey questionnaire which is composed of 36 items that assess the following eight dimensions or scales: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health. For each of the eight domains, scores were transformed linearly to a scale ranging from 0 (maximal impairment) to 100 (no impairment).

Physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain and general health reflect the physical component score (PCS), whereas vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health comprise the mental component score (MCS). PCS and MCS were computed using equations developed by Ware and Kosinski .

1.2.3.2

Sleep quality

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) assesses sleep quality during the previous month and differentiates “good” and “bad” sleepers . Sleep quality is a complex phenomenon that implies several dimensions, each of them analysed by the PSQI. This questionnaire includes 19 self-assessment questions and five questions asked to the life partner, spouse or roommate (depending on the cases). These questions correspond to seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. Only the self-assessment questions are included in the final score. The seven components add up for a final global score going from 0 to 21 points, 0 meaning there are no difficulty and 21 indicating major difficulties. A global PSQI score greater than 5 suggests significant sleep disturbances.

1.2.3.3

Anxious and depressive disorders

The HAD scale can screen for the most common psychological disorders: anxiety (sub-score HAD-A) and depression (sub-score HAD-D). This test can validate the existence of symptoms and evaluated their severity . It includes 14 items on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3. Seven questions focus on anxiety (Total A) and seven others on the depressive dimensions (total D) leading to two different scores (maximal grade for each score = 21). The various depression levels correspond to slight (score 8–10), moderate (11–14) and severe (≥15), and these same thresholds are used to evaluate anxiety. For the global score (total A + total D), the thresholds are respectively 19 and 13 for major and minor depressive states. Well-being (HAD-M) was evaluated with a scale going from 0 (“I don’t feel well at all”) to 10 (“I feel completely well”). This subjective measure was added for information but has not been scientifically validated.

1.2.3.4

Cardiopulmonary stress test

The peak power output (PPO) was determined by a test on an ergocycle with electromagnetic braking (Ergometrics 900, Ergoline, Germany). It corresponds to the power reached at the last stage of the test. The initial power was set at 30 W with a 15 W/min increase in coronary heart disease patients and 10 W/min in chronic heart failure patients. This progressive increase test was performed under continuous 12-Lead ECG monitoring. Blood pressure was checked every two minutes during the stress test and during the 6-minute recovery time (3-minute active recovery and 3-minute-passive recovery). The Borg scale was used to evaluate the rate of perceived exertion from 6 to 20 . The stress test was stopped when the patient was not able to maintain the required power or when the score of perceived exertion was at 15–17/20, in case of severe angina pectoris (>5/10), severe arrhythmia, drop in blood pressure >10 mmHg or ST-segment depression >2 mm .

1.2.3.5

Anthropometric parameters

The formula used for calculating BMI was weight in kilograms (kg) divided by height in meters (m) squared. The waist circumference was determined with a measuring tape (e.g. K & E type) positioned halfway between the lower part of the ribcage and the hipbone .

1.2.4

Statistical analyses

The variables presented in this text, tables and figure are expressed by means with standard deviation or numbers and percentage. The changes were calculated as the difference between the POST value and the PRE value. To compare the changes related to the various parameters in response to the cardiac rehabilitation program, repeated measures ANOVA was used. The associations between score changes and physical and anthropometric parameters were studied with a linear regression model. To compare the proportion of depressive and anxious patients within the population, before and after the intervention, we used the χ 2 test. We used the Statview 5.1 software (SAS institute Inc. North Carolina, USA) for all analyses except the χ 2 for which we used the SigmaStat 3.5 software (Systat SoftWare, Inc. California, USA). We considered P ≤ 0.05 as significant.

1.3

Results

One hundred and one cardiac patients participated in this study after an acute cardiac event. The study was conducted at the Clinique Saint-Orens, cardiovascular rehabilitation centre ( Table 1 ). The patients included in the study were hospitalised for a mean stay duration of 27 ± 7 days (mean ± SD), 55% had diagnosed high blood pressure, 36% had type-2 diabetes with an ejection fraction at 50.2 ± 15.1%,

| n = 101 | |

|---|---|

| Age | 65 ± 12 |

| Weight (kg) | 79 ± 21 |

| Height (m) | 1.68 ± 0.1 |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 28 ± 6 |

| Gender (M/F) | 70/31 |

| Coronary pathology | 74 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) | 42 |

| Coronary angioplasty | 31 |

| Medical treatment | 1 |

| Chronic heart failure | 13 |

| Ischemic cardiomyopathy | 12 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 1 |

| Valvular insufficiency | 27 |

| Valve replacement | 16 |

| Bioprosthesis | 12 |

1.3.1

Patients’ characteristics upon admission on quality of life components

Depressive state and anxiety were found in 30% and 38% out of the 101 patients recruited. The scores indicated 17% of slight anxiety and 21% of moderate anxiety. Slight, moderate and severe depression was respectively suspected in 18%, 9% and 2% of patients. Furthermore, 76% of patients presented sleep disorders measured with the sleep quality index. Fifty percent of patients benefited from two sessions of psychological counselling during their stay.

1.3.2

Associations between the following components: quality of life, gender, anthropomorphic data and type of coronary revascularisation

The HAD-D and HAD-A scores were tightly inter-correlated ( r = 0.34, P = 0.0008). Women presented more depressive symptoms (score HAD-D 7.3 ± 4 vs 5.5 ± 3, P < 0.05) and a lesser physical health score (SF-36) (33.6 ± 9 vs 38.8 ± 8, P < 0.01) than men. There was a correlation between age and the HAD-M score ( r = 0.22, P = 0.03), as well as between age and depression ( r = 0.26, P < 0.01). Furthermore, a relationship was noted between sleep quality and anxiety ( r = 0.21, P = 0.03) or depression ( r = 0.19, P < 0.05).

Regarding the type of coronary revascularisation, the physical health score (SF-36) was lower in the group of patients who had coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) than for the group of patient who had coronary angioplasty (respectively 34.8 ± 8 vs 39.5 ± 8, P = 0.02). However, no correlation was established between quality of life and anthropometric.

1.3.3

Effects of the cardiac rehabilitation program

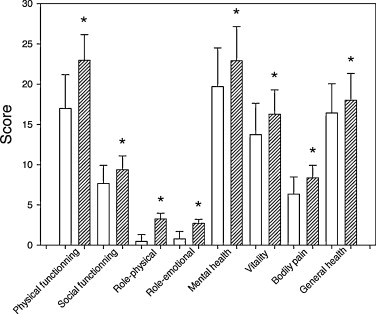

At the end of the program, we can report a 25% improvement on quality of sleep, a 29% decrease on anxiety levels and 32% decrease on depression levels ( P < 0.0001), as well as a 28% improvement on moral ( P < 0.0001) ( Table 2 ). Furthermore, the physical health score and the mental health score (SF-36) increased at the end of the cardiac rehabilitation program (11 and 14%, P < 0.0001, respectively). Each of the eight subscales (measuring the physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health) was also improved at the end of the hospital stay ( P < 0.0001) ( Fig. 1 ).

| Questionnaire | PRE | POST | Changes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 PCS | 37.4 ± 9.3 | 41.4 ± 9.0 * | 4 ± 0.3 (11) |

| SF-36 MCS | 43.9 ± 9.9 | 50.2 ± 9.3 * | 6 ± 0.6 (14) |

| PSQI | 9.4 ± 4.1 | 7.0 ± 4.2 * | –2 ± 0.2 (–25) |

| HAD-M | 6.5 ± 2.0 | 8.3 ± 1.5 * | 2 ± 0.5 (28) |

| HAD-A | 7.3 ± 3.6 | 5.2 ± 3.0 * | –2 ± 0.6 (–29) |

| HAD-D | 6.0 ± 3.9 | 4.1 ± 3.3 * | –2 ± 0.3 (–32) |

The rate of depressive patients went from 30 to 19% ( P = 0.06) and the rate of anxious patients went from 38 to 20% ( P < 0.005). We did not observe any difference between the group of patients who benefited from psychological counselling and the group of patients who did not. In other words, the two groups progressed in an identical manner in all QoL parameters.

The patients’ weight decreased (79.2 ± 21.3 vs 76.9 ± 20.2 kg; P < 0.0001), along with their BMI (27.8 ± 5.9 vs 27.0 ± 5.6; P < 0.0001) and their waist circumference (97.8 ± 13.7 vs 95.1 ± 12.6 cm; P < 0.0001). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values went down respectively from 127 ± 16 to 115 ± 17 mmHg ( P < 0.001), and from 70 ± 15 to 64 ± 9 mmHg ( P < 0.001). Regarding the measures collected during the cardiopulmonary stress test, we observed a significant improvement of the PPO (25%) and double product at PPO (17%) defined by HRmax × SBPmax in spite of changes to the maximal heart rate (HRmax) ( Table 3 ).

| PRE | POST | Change (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HR max (bpm) | 114.6 ± 32,1 | 126.5 ± 28.4 | 10 |

| Peak power output (W) | 98.9 ± 34,4 | 123.8 ± 44.7 *** | 25 |

| Double product at peak power output (bpm/mmHg) | 176.6 ± 54,9 | 206.1 ± 73.9 * | 17 |

| Systolic blood pressure at rest (mmHg) | 127 ± 16 | 115 ± 17 *** | –10 |

| Diastolic blood pressure at rest (mmHg) | 70 ± 14 | 64 ± 9 ** | –8 |

1.3.4

Associations between the changes obtained after cardiac rehabilitation training

No relationship was observed between quality of life score changes and anthropometric measures. Only weight loss was associated to decreased anxiety (HAD-A) ( r = 0.22, P = 0.03). Furthermore, an improved sleep quality was correlated to the mental health state (SF-36) ( r = 0.27, P < 0.01). Improved physical health (SF-36) was correlated to moral improvement (HAD-M) ( r = 0.22, P < 0.05). Finally, changes observed in the different scores after the cardiac rehabilitation program were not related to gender, age, initial severity level or type of coronary revascularisation procedure.

1.4

Discussion

We showed:

- •

a significant impact on quality of life as well as anxiety-depression after 4 weeks of cardiac rehabilitation training;

- •

no correlation between QoL improvement and anthropometric parameters, as well as between improved effort capacities, QoL and anxiety-depression.

1.4.1

Quality of life

Our study showed a short-term positive impact (4 weeks) of a cardiac rehabilitation program on the health of patients admitted in a cardiac rehabilitation centre. In fact, analysing the scores obtained on the SF-36 questionnaire revealed an improvement of physical and mental components, as well as the eight subscales, after following our 4-week cardiac rehabilitation program. These data match the results from Stahle et al. and Yohannes et al. who reported long-term benefits of cardiac rehabilitation on quality of life . These results also validate the ones from Hung et al. who showed the efficacy of physical exercise associated to weight lifting (three times a week for 8 weeks total) on improving quality of life measured with the MacNew heart disease health-related quality of life instrument in older patients with coronary artery diseases . The quick efficacy reported by our study could be explained by the multidisciplinary rehabilitation approach since adapted physical activity sessions (3 hours/day) were associated to relaxation sessions and personalized dietary follow-up. Furthermore, the literature has reported that the quality of life of post-MI patients is even more altered if they are diabetics . It becomes essential to focus on this population representing about 40% of coronary patients in our Centre. It is also highly relevant to take into account other cardiovascular risk factors since changes in health-related behaviours like diet; physical exercise and stopping smoking are even more effective when associated to early therapeutic care after acute coronary syndrome in order to reduce the risk of subsequent episodes .

1.4.2

Anxiety and depression

Decreased levels of anxiety and depression associated to an increase in moral supports the study from Worcester et al. showing the significant impact of physical exercise programs in correcting depressive symptoms observed in patients after myocardial infarction . Also, a better moral associated to regular exercise seems quite helpful in fighting off acute reactional depression generally observed after myocardial infarction . Our results confirm the data from Lavie and Milani’s study that showed the positive impact of cardiac rehabilitation in older patients, including decreased scores for anxiety (–29%), somatic symptoms (–35%) and depression (–27%), associated to a 13% improvement in the global quality of life score ( P < 0.0001) . According to Lavie and Milani, cardiac rehabilitation has a modest effect on the traditional risk factors because of its short duration, but it allows for reducing the prevalence of severe and moderate depression (among patients diagnosed at the beginning of the cardiac rehabilitation program) . In fact, it is very important to treat anxiety and depression symptoms during that time since it was recently proven that the latter affect the patient’s ability to improve exercise tolerance . When the exercise tolerance is improved, it is correlated to a decreased in cardiac mortality and complications . This result could be attributed to the fact that patients became more confident and were able to better face their health status thanks to the support of the Centre’s multidisciplinary team and other patients. Additional studies are necessary however in order to identify the mechanisms involved.

1.4.3

Sleep quality

Our results concur with the ones from a study based on 163 patients with coronary diseases highlighting the link between anxiety and depression syndromes and poor sleep quality, measured with the PSQI and the HAD scale . Furthermore, Johansson et al. noticed that these three symptoms were all correlated to fatigue, independently from MI severity (biomarkers, ejection fraction) justifying the need for cardiac rehabilitation training to improve quality of life parameters . Finally, Schiza et al. showed that after acute coronary syndrome patient had altered sleep parameters, leading to poor sleep quality . These alterations tend to fade away after 6 months suggesting a link with the underlying disease. These observations could explain the high prevalence (76%) of sleep disorders in our population.

1.4.4

Physical parameters and anthropometric data

The significant weight loss and thus decreased BMI observed in all our patients might be due to physical exercise associated to a proper diet . However, our patients are still overweight (BMI above 27 kg/m 2 ) with a large waist circumference upon discharge (100 ± 13 cm, in men vs 93 ± 11 cm, in women). These data are even more worrisome in women where the reference value for this intra-abdominal adiposity key variable is set at 88 cm by the NCEP/ATP III guidelines . Regarding this element, our rehabilitation program is probably not long enough (4 weeks) to bring these parameters down to normal values, according to the very poor initial profile of these patients. In this light, long-term cardiac exercise programs associated to a proper diet and nutrition seem quite necessary . Exercise tolerance measured by PPO increased by 25% a value comparable to expected results . In fact, a short-term program can increase patients’ self-confidence thus improving program compliance as well as their physical abilities. However, the impact on anthropometric variables will probably be longer to obtain and would be helped by a better compliance if the patients were less depressed. Even if we were not able to validate a link between improved exercise tolerance and quality of life, these changes are nevertheless important since they allow for a better social reinsertion, especially work-related . Finally, the decrease in blood pressure at rest is similar to the one observed in the meta-analysis of Pescatello et al. who reported a decrease in SBP and DBP at respectively 7.8 and 5.8 mmHg in patients with hypertension . However, given that exercise-induced blood pressure reduction is dependent on maintaining this exercise level and because it improves sleep quality , it becomes essential to pursue a long-term exercise routine.

1.4.5

Limits

The specific impact of each dimension of the patient’s comprehensive care (nutrition, medical, rehabilitation, psychological) could not be demonstrated but this study supports the use of multidisciplinary competencies in light of the encouraging results obtained after 4 weeks or rehabilitation program. However, the lack of significant correlations between the various QoL parameters and exercise tolerance could be due to the insufficient number of subjects and/or the short duration of our program. It seems necessary to look at a larger study with more patients and/or longer duration to discriminate the respective impact of each component of this therapeutic care. The SF-36 questionnaire is probably less adapted than a specific questionnaire such as the “MacNew heart disease health-related quality of life instrument” but this latter is not, for now, validated in French.

1.5

Conclusion

Comprehensive care for the cardiac patient after an acute event has an undeniable positive impact on the various aspects of physical and mental health but also on some psychological parameters such as anxiety, depression, moral and sleep quality. This study reinforces the importance of rehabilitation programs in stable cardiac patients in order to increase their quality of life, decrease their depressive state and, by that sole fact, improve their vital and functional prognosis. Finally, our results show that all patients progress independently of their age, gender or severity of their mental health when entering the program, which should incite physicians to propose and/or orientate cardiac patients more systematically towards cardiovascular rehabilitation programs still largely under-prescribed in France. This work is to be used as the basis for identifying patients who did not improve their quality of life or depression during the program and providing them with a closer psychological and cardiac monitoring and follow-up. These elements should be systematically assessed during patients’ cardiac rehabilitation care using quick questionnaires such as the HAD scale. Further studies are necessary to better understand the “kinetics” of mood and quality of life during cardiac rehabilitation and correlate it to a better compliance to physical exercise and lifestyle changes.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La réadaptation cardiaque fondée sur l’exercice physique a largement montré son efficacité pour réduire la morbimortalité des patients cardiaques . Ses bénéfices s’expliquent par une amélioration des paramètres lipidiques et des chiffres tensionnels, par la prévention du diabète, l’augmentation du sevrage tabagique, la perte de poids, le mieux-être et ce, associé à une amélioration de la tolérance à l’effort, valeur pronostique indépendante de morbimortalité . Même si la réadaptation cardiaque en centre spécialisé est largement sous-prescrite en France, elle reste néanmoins une période décisive pour la prise en charge psychologique du patient afin de lui apporter un soutien adapté et personnalisé. L’étude Interheart a bien documenté que le stress est associé à une augmentation du risque d’infarctus du myocarde (IDM) . Par ailleurs, les dépressions légères à modérées affectent un grand nombre de patients ayant subi un IDM et le profil psychologique de ces derniers est un facteur indépendant de mortalité à un an de suivi . Si l’impact de la réadaptation cardiaque sur l’amélioration du profil métabolique et de l’aptitude physique est bien documenté , peu d’études ont cependant examiné l’impact de ces programmes sur certains facteurs de qualité de vie, notamment en phase de post-revascularisation coronaire et il est aujourd’hui difficile de conclure du fait de l’hétérogénéité des études sur les patients coronariens . Belardinelli et al., puis l’étude HF-Action ont montré que la qualité de vie des patients insuffisants cardiaques est améliorée par l’exercice lors d’une prise en charge en ambulatoire à moyen et long terme . À ce propos, Stahle et al. ont montré l’efficacité d’un programme d’exercice seul (d’une durée d’un an) sur la qualité de vie estimée à l’aide du questionnaire Karolinska chez des patients coronariens âgés . Récemment, Yohannes et al. ont montré que six semaines de réadaptation cardiaque améliorent la qualité de vie estimée par le SF-36, ainsi que l’anxiété et la dépression mesurées à l’aide du questionnaire HAD, et que ces bénéfices sont maintenus à douze mois . Toutefois, aucune étude n’a documenté, à ce jour, les effets à court terme d’un programme de réadaptation cardiaque sur certains critères de la qualité de vie dont les différentes composantes de santé physique et mentale (évaluées par le questionnaire SF-36) et la qualité du sommeil, ainsi que leurs relations avec les composantes physiques et anthropométriques chez des patients cardiaques admis en hospitalisation complète en centre de rééducation.

Le but principal de cette étude est donc d’évaluer si un programme global, court et intense, de réadaptation cardiaque de quatre semaines, exerce un impact favorable sur différents paramètres de qualité de vie tels que l’anxiété, la dépression, la qualité de sommeil, ainsi que la santé physique et mentale. L’objectif secondaire est de vérifier s’il existe des relations entre l’amélioration de certains paramètres anthropométriques, de la tolérance à l’effort et de la qualité de vie.

2.2

Méthodes

2.2.1

Population

Les patients ont été recrutés à la clinique Saint-Orens. Le protocole était proposé à tous les patients référés pour un programme de réadaptation cardiaque en hospitalisation complète après un événement aigu (geste interventionnel ou chirurgical ou décompensation aiguë). Les critères d’exclusion étaient : un angor instable, pacemaker, hypertension artérielle non contrôlée, arythmies sévères, toutes autres pathologies neuro-orthopédiques ayant un retentissement majeur sur la capacité d’exercice. Tous les patients ont donné leur consentement éclairé par écrit pour participer à ce protocole qui a été révisé et approuvé par le comité d’éthique de la clinique Saint-Orens.

2.2.2

Programme global de réadaptation cardiaque

Ce dernier comportait : l’optimisation du traitement médicamenteux, le contrôle des facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire, le ré-entraînement à l’effort, des activités gymniques, un suivi diététique, des séances d’éducation thérapeutique et un suivi psychologique pour certains d’entre eux.

Le programme d’activité physique était d’une durée de trois heures par jour, 5,5 jours par semaine. L’activité journalière comportait :

- •

une activité de ré-entraînement à l’effort réalisée sur cyclo-ergomètre ou tapis roulant d’une durée de 45 minutes ;

- •

une séance de marche à l’extérieur d’une durée d’une heure, à la fréquence cardiaque cible déterminée par l’épreuve d’effort, c’est à dire 60 à 80 % de la fréquence cardiaque de réserve .

La perception de l’effort était mesurée de 6 à 20 à l’aide de l’échelle de Borg . De plus, les patients participaient à des séances de musculation, des activités de gymnastique, de la relaxation, du Qi kong ou de l’aquagym. Ces dernières activités étaient d’une durée de 45 minutes (échauffement et récupération inclus). Chaque séance était encadrée par un kinésithérapeute ou un professeur d’activité physique adaptée et supervisée par un médecin cardiologue. En complément du programme d’activité physique, les patients participaient à des séances d’éducation thérapeutique, animées par l’équipe pluridisciplinaire, sous forme d’ateliers pratiques ou de conférences portant sur les facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire et la connaissance du traitement (≈ trois à quatre heures par semaine).

2.2.3

Mesures

Elles étaient réalisées à deux reprises, soit le lendemain de l’entrée (PRE) et la veille de la sortie (POST). Chaque patient était informé sur la manière de remplir les questionnaires et ce, deux fois durant son hospitalisation. Les questionnaires lui étaient remis directement dans sa chambre et il les remplissait seul. En cas d’incompréhensions relatives à certaines questions, le patient pouvait consulter le professeur d’activité physique adaptée pour plus d’informations.

2.2.3.1

Qualité de vie

La qualité de vie liée à la santé a été mesurée en utilisant la version française du SF-36 . Le SF-36 comprend 36 questions regroupées en huit dimensions correspondant chacune à un aspect différent de la santé : l’activité physique, les limites dues à l’état physique, les douleurs physiques, la santé perçue, la vitalité, la relation avec les autres, la santé psychique et les limites dues à l’état psychique. Pour chaque dimension, la somme des scores des items a été transformée linéairement en une échelle variant de 0 (affaiblissement maximal) à 100 (aucun affaiblissement). L’activité physique, la douleur physique et les limites dues à l’état physique reflètent le score de la composante physique (PCS), tandis que la santé perçue, la vitalité, la santé psychique, la relation avec les autres et les limites dues à l’état psychique traduisent le score de la composante mentale (MCS). Les PCS et MCS ont été calculés en utilisant les équations développées par Ware et Kosinski .

2.2.3.2

Qualité du sommeil

L’indice de Qualité du Sommeil de Pittsburgh (IQSP), qui mesure la qualité de sommeil pendant le mois précédent, distingue les « bons » des « mauvais » dormeurs . La qualité du sommeil est un phénomène complexe qui implique plusieurs dimensions dont chacune d’entre elles est analysée par l’IQSP. Ce questionnaire comprend 19 questions d’auto-évaluation et cinq questions posées au conjoint ou compagnon de chambre (suivant le cas). Ces questions correspondent à sept composantes : la qualité subjective du sommeil, la latence au sommeil, la durée du sommeil, l’efficacité du sommeil, les perturbations du sommeil, la prise éventuelle de médications pour des troubles du sommeil et les perturbations du fonctionnement diurne. Seules les questions d’auto-évaluation sont incluses dans le calcul du score. Les sept composantes s’additionnent pour donner un score global allant de 0 à 21 points, 0 signifiant qu’il n’y a aucune difficulté, et 21 indiquant au contraire des difficultés majeures. Un total de l’IQSP supérieur à 5 est considéré suggestif de perturbations significatives du sommeil.

2.2.3.3

Troubles anxieux et dépressifs

L’échelle HAD permet de dépister les troubles psychologiques les plus communs : l’anxiété (sous-score HAD-A) et la dépression (sous-score HAD-D). Ce test permet d’identifier l’existence d’une symptomatologie et d’en évaluer la sévérité . Elle comporte 14 items cotés de 0 à 3. Sept questions se rapportent à l’anxiété (total A) et sept autres à la dimension dépressive (total D), permettant ainsi l’obtention de deux scores (note maximale de chaque score = 21). Les différents niveaux de dépression correspondent à légère (score 8–10), modérée (11–14) et sévère (≥ 15), et ces mêmes seuils sont utilisés pour évaluer l’anxiété. Pour le score global (total A + total D), les seuils sont respectivement de 19 et de 13 pour les états dépressifs majeurs et mineurs. Le moral (HAD-M) a été estimé à l’aide d’une échelle allant de 0 (« je ne me sens pas bien du tout ») à 10 (« je me sens parfaitement bien »). Cette mesure subjective a été ajoutée à titre indicatif mais n’a fait l’objet d’aucune validation.

2.2.3.4

Épreuves d’effort cardiopulmonaire

Le pic de puissance (PP) a été déterminé par un test incrémenté sur bicyclette ergométrique à freinage électromagnétique (Ergometrics 900, Ergoline, Allemagne). Il correspond à la puissance atteinte au dernier palier du test. La puissance initiale était de 30 W pour une incrémentation de 15 W/min chez les sujets coronariens et de 10 W/min chez ceux présentant une insuffisance cardiaque. Le test incrémenté était réalisé sous ECG continu en 12 dérivations. La pression artérielle était contrôlée toutes les deux minutes pendant le test et durant les six minutes de récupération (trois minutes active et trois minutes passive). La perception de l’effort était mesurée de 6 à 20 à l’aide de l’échelle de Borg . Le test était terminé lorsque le patient n’était plus capable de maintenir la puissance requise, et si le score de perception de l’effort était de 15–17/20, en présence d’angor sévère (> 5/10), d’arythmies sévères, d’une chute de la pression artérielle supérieure à 10 mmHg ou d’un sous-décalage du segment ST supérieure à 2 mm .

2.2.3.5

Anthropométrie

L’IMC a été calculé par le rapport de la masse corporelle (kg) par la taille élevée au carrée (m 2 ). Le tour de taille a été mesuré à l’aide d’un ruban anthropométrique de type K & E, placé à mi-distance entre l’extrémité inférieure de la cage thoracique et les crêtes iliaques .

2.2.4

Analyses statistiques

Les variables présentées dans le texte ainsi que dans les tableaux et la figure sont la moyenne affectée de la déviation standard ou le nombre et le pourcentage. Les changements ont été calculés comme la différence entre la valeur POST et la valeur PRÉ. Pour comparer les changements relatifs aux différents paramètres en réponse au programme de réadaptation cardiaque, nous avons utilisé une analyse de variance à mesures répétées (Anova). Les associations entres les changements de score et les paramètres physiques et anthropométriques ont été étudiés à l’aide d’une régression linéaire. Pour comparer la proportion de patients dépressifs et anxieux au sein de la population, avant et après l’intervention, nous avons utilisé le test du χ 2 . Nous avons utilisé le logiciel Statview 5.1, SAS institute Inc. North Carolina (États-Unis) pour toutes les analyses hormis le test du χ 2 pour lequel nous avons utilisé le logiciel SigmaStat 3.5, Systat SoftWare, Inc. Californie (États-Unis). Nous avons considéré un p ≤ 0,05 comme significatif.

2.3

Résultats

Cent un patients cardiaques au décours d’un événement aigu ont participé à cette étude réalisée au sein de la clinique Saint-Orens, centre de rééducation cardiovasculaire ( Tableau 1 ). Les patients inclus dans l’étude dont 55 % présentaient une hypertension artérielle (HTA) diagnostiquée, 36 % un diabète de type 2, et dont la fraction d’éjection était de 50,2 ± 15,1 %, étaient suivis en hospitalisation complète durant 27 ± 7 jours (moyenne ± SD).