Severe Arthritis Treated by Total Trapezium Excision and Soft-Tissue Reconstruction

Mark C. Shreve

Steven D. Maschke

INTRODUCTION

Thumb basilar joint arthritis is a frequent cause of radial-sided wrist pain and a common pathologic entity in the United States affecting most often women in their fifth to seventh decades of life. Radiographic evidence of thumb carpometacarpal (CMC) arthritis is present in 25% of men and 40% of women over the age of 75 years (1). Despite this high prevalence of radiographic disease, not all patients experience pain or disability (2). Eaton described the stages of thumb CMC arthritis ranging from a normally appearing joint on radiographs with mild widening of the joint space, to severe arthritic changes and pantrapezial involvement (3,4). Patients at each of the stages of CMC arthritis may experience pain, instability, and limitations in thumb motion and prehensile function due to their basilar joint disease.

After nonsurgical treatment with anti-inflammatory medications, therapy, splinting, and injections has failed to provide adequate pain relief and function, operative management can be explored. In order to restore a pain-free, stable, and functional thumb, many different surgical procedures have been described. First described by Gervis (5) in 1949, simple excision of the trapezium has become a mainstay of operative treatment for thumb basal joint arthritis. Froimson (6) later described adding an interposition arthroplasty into the space created by excision of the trapezium to prevent subsidence of the first metacarpal. Eaton and Littler (4) described volar ligament reconstruction using the flexor carpi radialis tendon to treat mild basal joint arthritis. Burton and Pellegrini (7) further modified simple trapeziectomy by adding a ligament reconstruction in addition to a tendon interposition, which has become the most widely performed operation for thumb basal joint arthritis. Other procedures range from partial trapeziectomy, first metacarpal osteotomy, basal joint arthroscopy, and implant arthroplasty, which are detailed in other sections of this book. This chapter describes our technique of trapezial excision with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition.

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

When deciding which surgical procedure is appropriate for a patient, it is important to determine the clinical stage of basilar joint arthritis. The most widely used staging system is that of Eaton and Glickel (3,8). Although recently the interobserver reliability has been called into question (9,10), it is still a useful tool, especially when discussing diagnosis and treatment options with patients. Stage I disease is defined by either normal radiographs or thumb CMC joint space widening due to synovitis. Patients in this stage are often times younger and have pain due to excessive basal joint laxity. Stage II is manifested by the beginnings of thumb CMC joint space narrowing with osteophytes and/or loose body formation less than 2 mm. Stage II patients are typically in their fourth and fifth decades. Stage III arthritis is manifested by significant CMC joint space narrowing or complete joint space destruction with osteophytes and loose body formation more than 2 mm. These patients are typically older, active adults in their fifth through seventh decades and more commonly females. Finally, stage IV disease has the same radiographic findings as stage III but with the addition of scaphotrapezial joint arthritic changes.

Indications for trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition are those patients with more severe arthritic changes about the thumb basal joint, typically patients in stages II, III, and IV. However, we have performed complete excision of the trapezium with ligament reconstruction in patients with radiographic stage I disease with good long-term results.

Potential alternatives to total trapezial excision and ligament reconstruction with tendon interposition have been described and may be considered in those patients in which the disease is limited and radiographic evidence is at stage I. These patients are potential candidates for more limited procedures such as subtotal trapezial excision with ligament reconstruction, joint arthroscopy, metacarpal extension osteotomy, or continued nonsurgical management.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Patients with basal joint arthritis typically complain of pain with activities requiring repetitive pinching, gripping, and twisting. Common complaints include difficulty with opening jars or handwriting, but vary depending on the patient’s specific occupation or hobbies with varied demands placed on individual hand function. Aesthetic complaints of enlargement of the thumb base are common and occur secondary to gradual dorsal-radial subluxation of the thumb metacarpal on the trapezium with increasing basal joint laxity (8). A thorough history and physical examination is important, as often concomitant de Quervain’s tenosynovitis and/or carpal tunnel syndrome is present in patients with basal joint arthritis (11,12). Both can contribute to radial-sided wrist pain and intrinsic thumb weakness and disability. The first dorsal compartment over the dorsal-radial aspect of the distal radius, which contains the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis, should be evaluated for tenderness and swelling. Thorough evaluation for carpal tunnel syndrome is critical to define any concomitant compression of the median nerve. Often, deformity from basilar joint arthritis can mask weakness of the thenar musculature found in severe carpal tunnel syndrome. When present, concomitant carpal tunnel syndrome and/or first compartment tendonitis should be surgically addressed at the same time as the thumb CMC reconstruction.

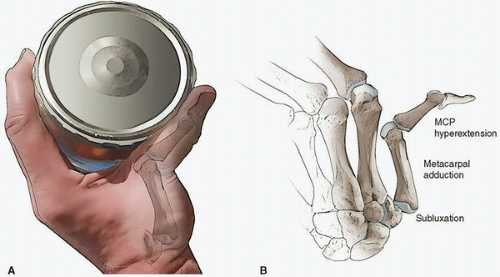

Objective measurement of lateral and key pinch should be performed and compared to the opposite hand. Evaluation of posture and function of the thumb metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint is also necessary for preoperative planning. Observe the patient’s thumb during active pinch, which will not only accentuate the dorsal subluxation of the metacarpal base but also unmask any underlying MP joint collapse into hyperextension (Fig. 26B-1). MP hyperextension greater than 30 degrees and/or valgus instability should be addressed at the time of surgery with either MP joint arthrodesis or volar capsulodesis (13,14,15).

Radiographic evaluation of the thumb should be performed preoperatively. Standard posteroanterior, lateral, and oblique views should be obtained. An adequate lateral view will have the MP joint sesamoids superimposed. A basal joint stress view can also be obtained, which is an anteroposterior view of both thumbs obtained while having the patient press the radial aspect of the thumb tips together thus comparing the basal joint subluxation side to side (3). These radiographs should be scrutinized for involvement of the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) joint, as concomitant STT arthritis may alter the surgical plan.

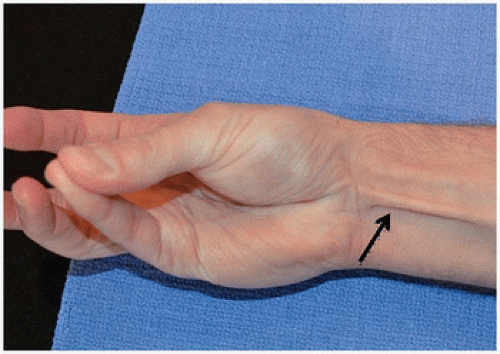

When planning to perform ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition by harvesting the palmaris longus tendon, it is helpful to document the presence and size of this tendon preoperatively. We ask our patients to pinch the tips of the thumb and small finger together while flexing

their wrist; this maneuver will define the palmaris longus when present (Fig. 26B-2). Absence of the palmaris longus varies between ethnic groups, but is generally regarded as being absent in approximately 15% of the population (16). When present, size can vary between patients.

their wrist; this maneuver will define the palmaris longus when present (Fig. 26B-2). Absence of the palmaris longus varies between ethnic groups, but is generally regarded as being absent in approximately 15% of the population (16). When present, size can vary between patients.

FIGURE 26B-1 Clinical (A) and radiographic (B) examples of thumb MP joint hyperextension secondary to advanced thumb CMC disease. |

FIGURE 26B-2 Ask the patient to pinch the tips of the thumb and small finger together while flexing the wrist to accentuate and determine the presence of the palmaris longus tendon (arrow). |

There has been concern in the literature regarding harvest of the flexor carpi radialis tendon. Some have found impaired flexion torque and diminished flexion fatigue resistance after full FCR tendon harvest (17), while others have found no impairment postoperatively (18). Recently, Beall et al. (19) noted that 79% of patients at least partially regenerated their FCR tendon after full harvest based on MRI studies performed postoperatively. In practice, we routinely harvest the entire FCR tendon and have not experienced complaints of subjective pain or weakness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree