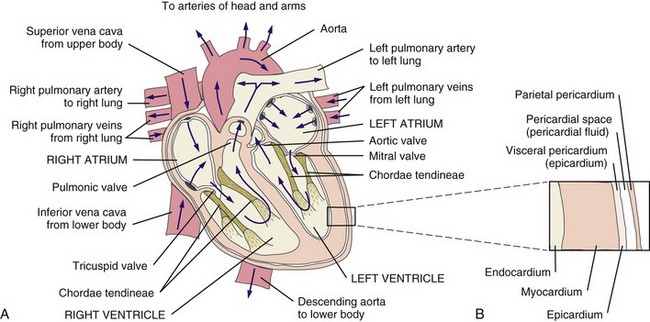

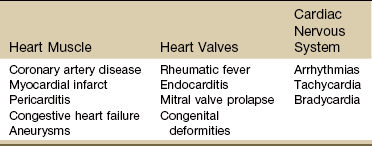

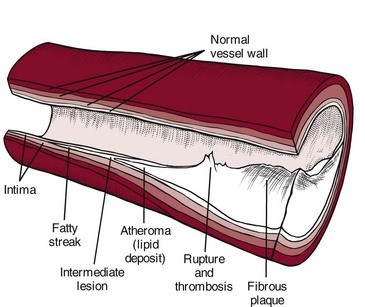

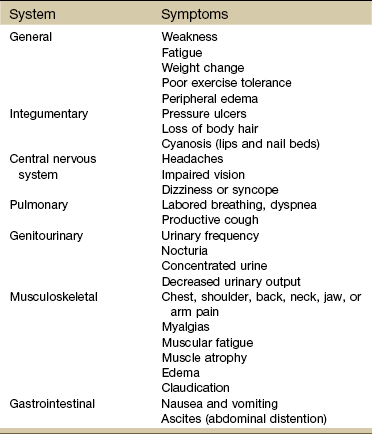

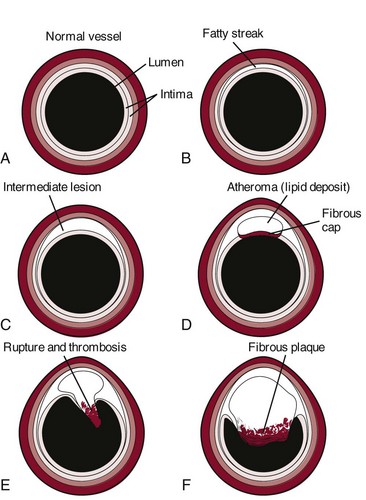

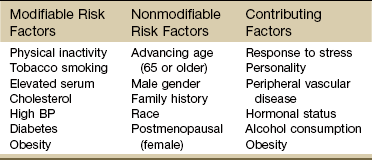

Chapter 6 The cardiovascular system consists of the heart, capillaries, veins, and lymphatics and functions in coordination with the pulmonary system to circulate oxygenated blood through the arterial system to all cells. This system then collects deoxygenated blood from the venous system and delivers it to the lungs for reoxygenation (Fig. 6-1). Heart disease remains the leading cause of death in industrialized nations. In the United States alone, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is responsible for approximately one million deaths each year. One in three Americans has some form of cardiovascular disease. The American Heart Association (AHA) reports that about half of all deaths from heart disease are sudden and unexpected.1 Information about heart disease is changing rapidly. Part of the therapist’s intervention includes patient/client education. The therapist can access up-to-date information at many useful websites (Box 6-1). Cardinal symptoms of cardiac disease usually include chest, neck and/or arm pain or discomfort, palpitation, dyspnea, syncope (fainting), fatigue, cough, diaphoresis, and cyanosis. Edema and leg pain (claudication) are the most common symptoms of the vascular component of a cardiovascular pathologic condition. Symptoms of cardiovascular involvement should also be reviewed by system (Table 6-1). TABLE 6-1 Cardiovascular Signs and Symptoms by System Modified from Goodman CC, Fuller K: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2009, WB Saunders. Radiating pain down the arm follows the pattern of ulnar nerve distribution. Pain of cardiac origin can be experienced in the somatic areas because the heart is supplied by the C3 to T4 spinal segments, referring visceral pain to the corresponding somatic area (see Fig. 3-3). For example, the heart and the diaphragm, supplied by the C5-6 spinal segment, can refer pain to the shoulder (see Figs. 3-4 and 3-5). Noncardiac chest pain can be caused by an extensive list of disorders requiring screening for medical disease. For example, cervical disk disease and arthritic changes can mimic atypical chest pain. Chest pain that is attributed to anxiety, trigger points, cocaine use, and other noncardiac causes is discussed in Chapter 17. Dyspnea, also referred to as breathlessness or shortness of breath, can be cardiovascular in origin, but it may also occur secondary to a pulmonary pathologic condition (see also Chapter 7), fever, certain medications, allergies, poor physical conditioning, or obesity. Early onset of dyspnea may be described as having to breathe too much or as an uncomfortable feeling during breathing after exercise or exertion. Examination of the cervical spine may include vertebral artery tests for compression of the vertebral arteries.2–5 If signs of eye nystagmus, changes in pupil size, or visual disturbances and symptoms of dizziness or lightheadedness occur, care must be taken concerning any treatment that follows. It has been suggested, however, that other factors, such as individual sensitivity to extreme head positions, age, and vestibular responsiveness, could affect the results of these tests.6 The test may be contraindicated in individuals with cervical spine fusion, Down syndrome (due to cervical hypermobility and/or instability), or other cervical spine instabilities. Although there is controversy and uncertainty about the safety and accuracy of vertebral artery tests, long-term complications have not been reported as a result of administering these tests.7,8 For a video of how to perform this test, go to www.youtube.com and type in “Gans video vertebral artery test.” Cough (see also Chapter 7) is usually associated with pulmonary conditions, but it may occur as a pulmonary complication of a cardiovascular pathologic complex. Left ventricular dysfunction, including mitral valve dysfunction resulting from pulmonary edema or left ventricular CHF, may result in a cough when aggravated by exercise, metabolic stress, supine position, or PND. The cough is often hacking and may produce large amounts of frothy, blood-tinged sputum. In the case of CHF, cough develops because a large amount of fluid is trapped in the pulmonary tree, irritating the lung mucosa. Other accompanying symptoms may include jugular vein distention (JVD; see Fig. 4-44) and cyanosis (of lips and appendages). Right upper quadrant pain described as a constant aching or sharp pain may occur secondary to an enlarged liver in this condition. Other noncardiac causes of leg pain (e.g., sciatica, pseudoclaudication, anterior compartment syndrome, gout, peripheral neuropathy) must be differentiated from pain associated with peripheral vascular disease. Low back pain associated with pseudoclaudication often indicates spinal stenosis. The discomfort associated with pseudoclaudication is frequently bilateral and improves with rest or flexion of the lumbar spine (see also Chapter 14). The therapist may see signs of cardiac dysfunction as abnormal responses of heart rate and BP during exercise. The therapist must remain alert to a heart rate that is either too high or too low during exercise, an irregular pulse rate, a systolic BP that does not rise progressively as the work level increases, a systolic BP that falls during exercise, or a change in diastolic pressure greater than 15 to 20 mm Hg (Case Example 6-1). Monitor vital signs in anyone with known heart disease. Some BP lowering medications can keep a client’s heart rate from exceeding 90 bpm. For these individuals the therapist can monitor heart rate, but use perceived rate of exertion (PRE) as a gauge of exercise intensity. See Chapter 4 for more specific information about vital sign assessment. Three components of cardiac disease are discussed, including diseases affecting the heart muscle, diseases affecting heart valves, and defects of the cardiac nervous system (Table 6-2). Hyperlipidemia refers to a group of metabolic abnormalities resulting in combinations of elevated serum total cholesterol (hypercholesterolemia), elevated low-density lipoproteins, elevated triglycerides (hypertriglyceridemia) and decreased high-density lipoproteins. These abnormalities are the primary risk factors for atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease.9–11 Statin medications (e.g., Zocor, Lipitor, Crestor, Lescol, Mevacor, Pravachol) are used to reduce low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. While statins are generally well tolerated, there is a wide body of medical literature that associates the adverse reaction of myalgia and the more serious reaction of rhabdomyolysis with statin medications.11,12 If detected early, statin-related symptoms can be reversible with reduction of dose, selection of another statin, or cessation of statin use.13–15 Screening for Side Effects of Statins: Myalgia and myopathy (including respiratory myopathy) are the most common myotoxic event associated with statins; joint pain is also reported.16,17 The incidence of myotoxic events appears to be dose-dependent. Rates of adverse events from statins vary in the literature from 5% up to 18%18 but with an increasing number of people taking these medications, physical therapists can expect to see a rise in the prevalence of this condition among the older age group.19,20 Monitoring for elevated serum liver enzymes and creatine kinase are significant laboratory indicators of muscle and liver impairment.21 Symptoms of mild myalgia (muscle ache or weakness without increased creatine kinase [CK] levels), myositis (muscle symptoms with increased CK levels), or frank rhabdomyolysis (muscle symptoms with marked CK elevation; more than 10 times the normal upper limit) range from 1% to 7%.11 Muscle soreness after exercise that is caused by statin use may go undetected even by the therapist. Awareness of potential risk factors and monitoring in anyone taking statins and any of these additional risk factors is advised. Muscular symptoms are more common in older individuals (Case Example 6-2).11,22 Other risk factors include23: • Age over 80 (women more than men) • Drinks excessive grapefruit juice daily (more than 1 quart/day) • Use of other medications (e.g., cyclosporine, some antibiotics, verapamil, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] protease inhibitors, some antidepressants)23 Muscle aches and pain, unexplained fever, nausea, vomiting and dark urine can potentially be signs of myositis and should be referred to a physician immediately. Risk for statin-induced myositis is highest in people with liver disease, acute infection, and hypothyroidism. Severe statin-induced myopathy can lead to rhabdomyolysis (enzyme leakage, muscle cell destruction, and elevated CK levels). Rhabdomyolysis is associated with impaired renal and liver function. Screening for liver impairment (see Chapter 9) in people taking statins is an important part of assessing for rhabdomyolysis (see further discussion of rhabdomyolysis in Chapter 9).24 The therapist will need to perform clinical tests and measures to differentiate exercise-related muscle fatigue and soreness from statin-induced symptoms. For example, exercise-induced muscle fatigue and soreness should be limited to the muscles exercised and resolve within 24 to 48 hours. Statin-related weakness may involve muscles not recently exercised and may progress or fail to show signs of improvement even after several days of rest.25 Dynamometer testing can be used as a valid and reliable indicator of change in muscle strength.26,27 Strength testing, combined with client history, risk factors, and performance on the Stair-Climbing Test and Six-Minute Walk test, may prove to be an adequate means of assessment to detect meaningful declines in functional status; baseline measures are important.25 CAD results from a person’s complex genetic makeup and interactions with the environment, including nutrition, activity levels, and history of smoking. Susceptibility to CVD may be explained by genetic factors, and it is likely that an “atherosclerosis gene” or “heart attack gene” will be identified.28 The therapeutic use of drugs that act by modifying gene transcription is a well-established practice in the treatment of CAD and essential hypertension.29,30 Atherosclerosis: Atherosclerosis is the disease process often called arteriosclerosis or hardening of the arteries. It is a progressive process that begins in childhood. It can occur in any artery in the body, but it is most common in medium-sized arteries such as those of the heart, brain, kidneys, and legs. Starting in childhood, the arteries begin to fill with a fatty substance, or lipids such as triglycerides and cholesterol, which then calcify or harden (Fig. 6-2). When fully developed, plaque can cause bleeding, clot formation, and distortion or rupture of a blood vessel (Fig. 6-3). Heart attacks and strokes are the most sudden and often fatal signs of the disease. Fig. 6-3 Updated model of atherosclerosis. New technology using intravascular ultrasound shows the whole atherosclerotic plaque and has changed the way we view things. The traditional model held that an atherosclerotic plaque in the blood vessel, particularly a coronary blood vessel, kept growing inward and obstructing flow until it closed off and caused a heart attack. This is not entirely correct. It is more accurate to say that in the normal vessel (A), penetration of lipoproteins into the smooth muscle cells of the intima produces fatty streaks (B) and the start of a coronary lesion forms. C and D, The coronary lesion grows outward first in a compensatory manner to maintain the open lumen. This is called positive remodeling, as the blood vessel tries to maintain an open lumen until it can do so no more. E, Only then does the plaque (atheroma) begin to build up, gradually pressing inward into the lumen with obstruction of blood flow and possible rupture and thrombosis, potentially leading to myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke. F, Vascular disease today is considered a disease of the wall. Some researchers like to say the disease is in the donut, not the hole of a donut, and that is a new concept.102 Thrombus: When plaque builds up on the artery walls, the blood flow is slowed and a clot (thrombus) may form on the plaque. When a vessel becomes blocked with a clot, it is called thrombosis. Coronary thrombosis refers to the formation of a clot in one of the coronary arteries, usually causing a heart attack. Spasm: Sudden constriction of a coronary artery is called a spasm; blood flow to that part of the heart is cut off or decreased. A brief spasm may cause mild symptoms that never return. A prolonged spasm may cause heart damage such as an infarct. This process can occur in healthy persons who have no cardiac history, as well as in those who have known atherosclerosis. Chemicals like nicotine and cocaine may lead to coronary artery spasm; other possible factors include anxiety and cold air. Risk Factors: In 1948 the United States government decided to investigate the etiology, incidence, and pathology of CAD by studying the residents of Framingham, Massachusetts, a typical small town in the United States. Over the next multiple decades, various aspects of lifestyle, health, and disease were studied. The research revealed important modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors associated with death caused by CAD. Since that time, an additional category, contributing factors, has been added (Table 6-3). The AHA has also developed a validated health-risk appraisal instrument to assess individual risk of heart attack, stroke, and diabetes (see Box 6-1). TABLE 6-3 Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease AHA Scientific Statements on Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke, 2010. Available on-line at www.heart.org (Risk Factors and Coronary Heart Disease). Accessed Sept. 1, 2010. 1. Exposure to bacteria such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Cytomegalovirus organisms31–33 2. Excess levels of homocysteine, an amino acid by-product of food rich in proteins 3. High levels of α-lipoprotein, a close cousin of LDL that transports fat throughout the body 4. High levels of fibrinogen, a protein that binds together platelet cells in blood clots34 5. Large amounts of C-reactive protein (CRP), a specialized protein necessary for repair of tissue injury.35,36 6. The presence of troponin T, a regulatory protein that helps heart muscle contract37 7. The presence of diagonal earlobe creases (under continued investigation)38–42 8. Past history of cancer treatment (cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic agents, trunk radiation)43 Therapists can assist clients in assessing their 10-year risk for heart attack using a risk assessment tool from the National Cholesterol Education program available at http://hin.nhlbi.nih.gov/atpiii/calculator.asp?usertype=prof. Women and Heart Disease: Many women know about the risk of breast cancer, but in truth, they are 10 times more likely to die of cardiovascular disease. While 1 in 30 deaths is from breast cancer, 1 in 2.5 deaths are from heart disease.44 Women do not seem to do as well as men after taking medications to dissolve blood clots or after undergoing heart-related medical procedures. Of the women who survive a heart attack, 46% will be disabled by heart failure within 6 years.45 Diabetes alone poses a greater risk than any other factor in predicting cardiovascular problems in women. Women with diabetes are seven times more likely to have cardiovascular complications and about half of them will die of CAD.46 One of the most important primary signs of CAD in women is unexplained, severe episodic fatigue and weakness associated with decreased ability to carry out normal activities of daily living (ADLs). Because fatigue, weakness, and trouble sleeping are general types of symptoms, they are not as easily associated with cardiovascular events and are many times missed by health care providers in screening for heart disease.47 Symptoms of weakness, fatigue and sleeping difficulty, and nausea have been reported as a common occurrence as much as a month prior to the development of acute MI in women (see Table 6-4). The classic pain of CAD is usually substernal chest pain characterized by a crushing, heavy, squeezing sensation commonly occurring during emotion or exertion. The pain of CAD in women, however, may vary greatly from that in men (see further discussion on MI in this chapter). Risk reduction in women focuses on lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation; low fat, low cholesterol diet; increased intake of omega-3 fatty acids; increased fruit, vegetable, whole grain intake; salt and alcohol limitation; and increased exercise and weight loss. If the woman has diabetes, strict glucose control is extremely important.48

Screening for Cardiovascular Disease

Signs and Symptoms of Cardiovascular Disease

Chest Pain or Discomfort

Dyspnea

Cardiac Syncope

Cough

Edema

Claudication

Vital Signs

Cardiac Pathophysiology

Conditions Affecting the Heart Muscle

Hyperlipidemia

Coronary Artery Disease

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Screening for Cardiovascular Disease