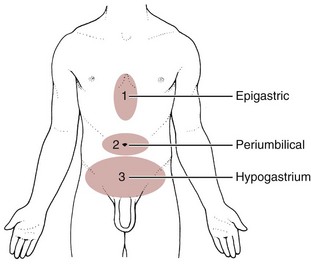

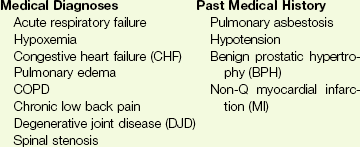

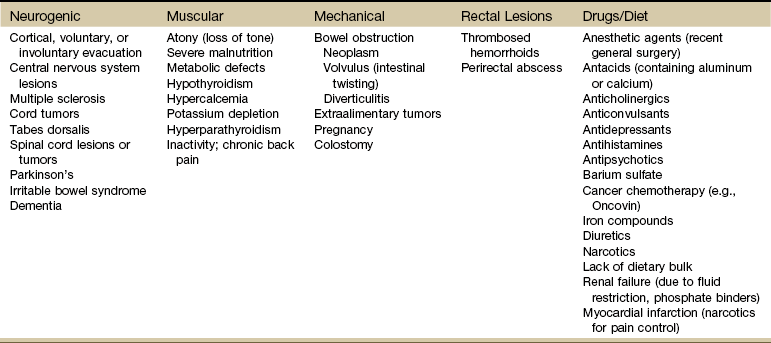

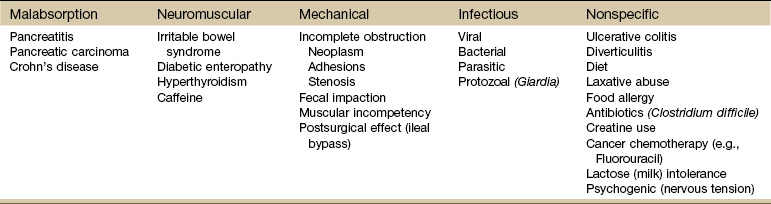

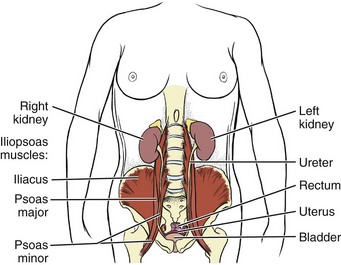

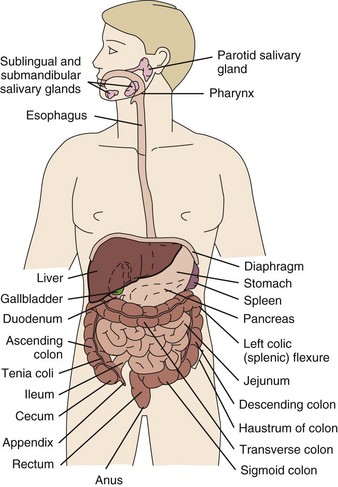

Chapter 8 A great deal of new understanding of the enteric system and its relationship to other systems has been discovered over the last decade. For example, it is now known that the lining of the digestive tract from the esophagus through the large intestine (Fig. 8-1) is lined with cells that contain neuropeptides and their receptors. These substances, produced by nerve cells, are a key to the mind-body connection that contributes to the physical manifestation of emotions.1,2 Fig. 8-1 Organs of the digestive system; see also Fig. 9-1. (From Hall JE: Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology, ed 12, Philadelphia, 2010, WB Saunders.) In addition to the classic hormonal and neural negative feedback loops, there are direct actions of gut hormones on the dorsal vagal complex. The person experiencing a “gut reaction” or “gut feeling” may indeed be experiencing the direct effects of gut peptides on brain function.3 Researchers estimate that more than two thirds of all immune activity occurs in the gut. There are more T cells in the intestinal epithelium than in all other body tissues combined. The gamma delta T cells form the forefront of the immune defense mechanism. They act as an early warning system in the cells lining the intestines, which are heavily exposed to microorganisms and toxins.4,5 In some people, the wall of the gut seems to have been breached, either because the network of intestinal cells develops increased permeability (a syndrome referred to as “leaky gut”) or perhaps because bacteria and yeast overwhelm it and migrate into the bloodstream. • GI bleeding (emesis, melena, red blood) • Epigastric pain with radiation to the back • Early satiety with weight loss • Tenderness over McBurney’s point (see Appendicitis this chapter) Visceral pain (internal organs) occurs in the midline because the digestive organs arise embryologically in the midline and receive sensory afferents from both sides of the spinal cord. The site of pain generally corresponds to dermatomes from which the visceral organs receive their innervation (see Fig. 3-3). Pain is not well localized because innervation of the viscera is multisegmental over up to eight segments of the spinal cord with fewer nerve endings than other sensitive organs. The most common primary pain patterns associated with organs of the GI tract are depicted in Fig. 8-2. Reasons for abdominal pain fall into three broad categories: inflammation, organ distention (tension pain), and necrosis (ischemic pain). The underlying cause can be life-threatening, requiring a quick assessment and fast referral. Pain in the periumbilical region (T9 to T11 nerve distribution) occurs with impairment of the small intestine (see Fig. 8-15), pancreas, and appendix. Primary pain in the periumbilical region usually sends the client to a physician. However, pain around the umbilicus may be accompanied by low back pain. In the healthy adult who is not obese and does not have a protruding abdomen, the umbilicus is level with the disk located anatomically between the L3 and L4 vertebral bodies. Pain in the lower abdominal region (hypogastrium) from the large intestine and/or colon may be mistaken for bladder or uterine pain (and vice versa) by its suprapubic location. Referred pain at the same anatomic level posteriorly corresponds to the sacrum (see Fig. 8-16). The large intestine and colon are innervated by T10 to L2, depending on the location (e.g., ascending, transverse, descending colon). Visceral afferent nerves from the liver, respiratory diaphragm, and pericardium are derived from C3 to C5 sympathetics and reach the central nervous system (CNS) via the phrenic nerve (see Fig. 3-3). The visceral pain associated with these structures is referred to the corresponding somatic area (i.e., the shoulder). Afferent stimuli from the colon, appendix, and pelvic viscera enter the 10th and 11th thoracic segments through the mesenteric plexus and lesser splanchnic nerves. Finally, the sigmoid colon, rectum, ureters, and testes are innervated by fibers that reach T11 to L1 segments through the lower splanchnic nerve and through the pelvic splanchnic nerves from S2 to S4. Referred pain may be perceived in the pelvis, flank, low back, or sacrum (Case Example 8-1). Hyperesthesia (excessive sensibility to sensory stimuli) of skin and hyperalgesia (excessive sensibility to painful stimuli) of muscle may develop in the referred pain distribution. As mentioned in Chapter 3, in the early stage of visceral disease, sympathetic reflexes arising from afferent impulses of the internal viscera can be expressed first as sensory, motor, and/or trophic changes in the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and/or muscles. The client may present with itching, dysesthesia, skin temperature changes, perspiration, or dry skin. Remember from our discussion of viscerogenic pain patterns in Chapter 3 that any structure touching the respiratory diaphragm can refer pain to the shoulder, usually to the ipsilateral shoulder, depending on where the direct pressure occurs. Anyone with upper back or shoulder pain and symptoms should be asked a few general screening questions about the presence of GI symptoms. Referred pain to the musculoskeletal system can occur alone, without accompanying visceral pain, but usually visceral pain (or other symptoms) precedes the development of referred pain. The therapist will find that the client does not connect the two sets of symptoms or fails to report abdominal pain and GI symptoms when experiencing a painful shoulder or low back, thinking these are two separate problems. For a more complete discussion of the mechanisms behind viscerogenic referred pain patterns, see Chapter 3. Most of what has been presented here has dealt with the sensory side of the clinical presentation. There can be motor effects of GI dysfunction, too. For example, contraction, guarding, and splinting of the rectus abdominis and muscles above the umbilicus can occur with dysfunction of the stomach, gallbladder, liver, pylorus, or respiratory diaphragm. Impairment of the ileum, jejunum, appendix, cecum, colon, and rectum are more likely to result in muscle spasm of the rectus abdominis below the umbilicus.6 At the same time, impairment of these GI structures can cause muscle dysfunction in the back (thoracic and lumbar spine) with loss of motion of the involved spinal segments. The clinical picture is one that is easily confused with primary pathology of the spinal segment.6 Once again, the history and associated signs and symptoms help the therapist sort through the clinical presentation to reach a differential diagnosis. A thorough screening process is essential in such cases. Other possible GI causes of dysphagia include peptic esophagitis (inflammation of the esophagus) with stricture (narrowing), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and neoplasm (Case Example 8-2). Dysphagia may be a symptom of many other disorders unrelated to GI disease (e.g., stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease). Certain types of drugs, including antidepressants, antihypertensives, and asthma drugs, can make swallowing difficult. Occult (hidden) GI bleeding can appear as mid-thoracic back pain with radiation to the right upper quadrant. Bleeding may not be obvious; serial Hemoccult tests and laboratory tests (checking for anemia and iron deficiency) are needed. A medical doctor should evaluate any type of bleeding. Ask about the presence of other signs such as blood in the vomit or stools (Box 8-1). Coffee ground emesis (vomit) may indicate a perforated peptic or duodenal ulcer. A screening interview and evaluation is especially helpful when clients have neglected medical treatment for so long that epigastric back pain may in turn have created biomechanical changes in muscular contractions and spinal movement. These changes eventually create pain of a biomechanical nature.7 The client then presents with enough true musculoskeletal findings such that a diagnosis of back dysfunction can be supported. However, the symptoms may be associated with a systemic problem. A good medical history can be a valuable tool in revealing the actual cause of the back pain. Early satiety occurs when the client feels hungry, takes one or two bites of food, and feels full. The sensation of being full is out of proportion with the time of the previous meal and the initial degree of hunger experienced. This can be a symptom of obstruction, stomach cancer, gastroparesis (slowing down of stomach emptying), peptic ulcer disease, and other tumors. Vertebral compression fractures can occur from a variety of disorders including osteoporosis and can result in severe spinal deformity. This deformity, along with severe back pain, can cause early satiety resulting in malnutrition.8 The Rome III Diagnostic criteria for functional constipation defines this condition as hard, lumpy stools; stools that are difficult to expel; infrequent stools (less than three per week); or a feeling of incomplete evacuation after defecation and general discomfort.9,10 Constipated clients with tender psoas trigger points (TrPs) may report anterior hip, groin, or thigh pain when the fecal bolus presses against the TrPs.11 Intractable constipation is called obstipation and can result in a fecal impaction that must be removed. Back pain may be the overriding symptom of obstipation, especially in older adults who do not have regular bowel movements or who cannot remember the last bowel movement was several weeks ago (Case Example 8-3). Changes in bowel habit may be a response to many other factors such as diet (decreased fluid and bulk intake), smoking, side effects of medication (especially constipation associated with opioids), acute or chronic diseases of the digestive system, extraabdominal diseases, personality, mood (depression), emotional stress, inactivity, prolonged bed rest, and lack of exercise (Table 8-1). Commonly implicated medications include narcotics, aluminum- or calcium-containing antacids (e.g., Alu-Tab, Basaljel, Tums, Rolaids), anticholinergics, tricyclic antidepressants, phenothiazines, calcium channel blockers, and iron salts. People with low back pain may develop constipation as a result of muscle guarding and splinting that causes reduced bowel motility. Pressure on sacral nerves from stored fecal content may cause an aching discomfort in the sacrum, buttocks, or thighs (Case Example 8-4). Diarrhea, by definition, is an abnormal increase in stool frequency and liquidity. This may be accompanied by urgency, perianal discomfort, and fecal incontinence. The causes of diarrhea vary widely from one person to another, but food, alcohol, use of laxatives and other drugs, medication side effects, and travel may contribute to the development of diarrhea (Table 8-2). This anaerobic bacterium colonizes the colon of 5% of healthy adults and over 20% of hospitalized patients. Clients receiving enteral (tube) feedings are at higher risk for acquisition of C. difficile and associated severe diarrhea. C. difficile is the major cause of diarrhea in patients hospitalized for more than 3 days. It is spread in an oral-fecal manner and is readily transmitted from patient to patient by hospital personnel. Fastidious handwashing, use of gloves, and extremely careful cleaning of bathroom, bed linen, and associated items are helpful in decreasing transmission.12 Athletes using creatine supplements to enhance power and strength in performance may experience minor GI symptoms. Muscle cramps, diarrhea, loss of appetite, weight gain, and dizziness occur in about 8% of the individuals taking these supplements. Therapists working with athletes should keep this in mind when hearing reports of GI distress. Many sports players do not even know how much creatine they are taking or are taking more than the recommended dose. Players as young as 13 years old have reported using creatine supplements.12a,13 The use of creatine for individuals under the age of 18 is not recommended; safety and efficacy of creatine has not been established in adolescents.14 Questions about laxative use can be asked tactfully during the Core Interview (see Chapter 2) when asking about medications, including over-the-counter (OTC) drugs such as laxatives. Encourage the client to discuss bowel management without drugs at the next appointment with the physician. The relationship between “gut” inflammation and joint inflammation is well known but not fully understood. Many inflammatory GI conditions have an arthritic component affecting the joints. For example, inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) is often accompanied by rheumatic manifestations; peripheral joint arthritis and spondylitis with sacroiliitis are the most common of these manifestations.15,16 Sacroiliac (SI) disease without inflammation has been documented as a primary cause of lower abdominal or inguinal pain.17 There may be a genetic component between inflammatory bowel disease and ankylosing spondylitis.18 The relationship between intestinal problems and joint involvement may also be explained by some type of “interface” between the bowel and the articular surface of joints.19,20 It is hypothesized that an antigen crosses the gut mucosa and enters the joint, which sets up an immunologic response. Arthralgia with synovitis and immune-mediated joint disease may occur as a result of this immunologic response.19 It is likely that an impaired antibacterial host defense and an uncontrolled proinflammatory response of the innate immune system are at fault.21 The bowel and joint symptoms may or may not occur at the same time. Usually, this type of arthralgia is preceded 1 to 3 weeks by diarrhea, urethritis, regional enteritis (Crohn’s disease), or other bacterial infection. The knees, ankles, shoulders, wrists, elbows, and small joints of the hands and feet (listed in order of decreasing frequency) are the peripheral joints affected most often.22 Spondylitis with sacroiliitis may present as low back pain and morning stiffness that improves with activity and restriction of chest and spinal movement. Radiographic findings are consistent with those of classic ankylosing spondylitis with bilateral SI joint involvement and bony erosion and sclerosis of the symphysis pubis, ischial tuberosities, and iliac crests. Ultimately, “bamboo spine” (see Fig. 12-4) will result. Heel pain is a frequent complaint, with swelling and tenderness located either posteriorly at the Achilles tendon insertion site, or inferiorly where the plantar fascia attaches to the calcaneus. Plantar fasciitis is common. Enthesopathy can also occur around the knee, ischial tuberosities, greater femoral trochanter, and costovertebral and manubriosternal joints.23 For a more complete discussion of joint pain and how to evaluate joint pain, see Chapter 3. A list of screening questions for joint pain is also reproduced in the Appendix as a quick reference in clinical practice. Pancreatic cancer can refer pain to the shoulder and is often missed as the cause. Fluid in the pleural space as a result of pancreatitis can present as shoulder pain. When the head of the pancreas is involved, the client could have right shoulder pain, but more often it manifests as mid-back or mid-thoracic pain sometimes lateralized from the spine on either side. When the tail of the pancreas is diseased, pain can be referred to the left shoulder (see Fig. 3-4). Pain may also occur in the right shoulder when blood is present in the abdominal cavity due to liver trauma (Case Example 8-5). Accumulation of blood in this area from a slow bleed of the spleen, liver, or stomach can produce bilateral shoulder pain. Abscess of the obturator or psoas muscle is a possible cause of lower abdominal pain, usually the consequence of spread of inflammation or infection from an adjacent structure. Since these muscles lie behind abdominal structures with no protective barrier, any infectious or inflammatory process affecting the abdominal or pelvic cavity can cause an obturator or psoas abscess (Figs. 8-3 and 8-4). Psoas abscesses most commonly result from direct extension of intraabdominal infections such as diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and appendicitis (see also the discussion on McBurney’s point later in this chapter).24 Kidney infection or abscess can also cause psoas abscess. Staphylococcus aureus (staph infection) is the most common cause of psoas abscess secondary to vertebral osteomyelitis. Peritonitis as a result of any infectious or inflammatory process can result in psoas abscess. Besides the diseases and conditions mentioned here, peritonitis can occur as a surgical complication. Look for a history of abdominal surgery of any kind, especially the anterior approach to spinal surgery for disk removal, spinal fusion, and insertion of a cage or artificial disk implant.25 In adult women, hematogenous psoas abscesses have been observed as a complication of spontaneous vaginal delivery.26,27 Regardless of the etiology, the abscess is usually confined to the psoas fascia but can spread to the hip, upper thigh, or buttock. The iliacus muscle in the iliac fossa joins with the lower portion of the psoas muscle. Osteomyelitis of the ilium or septic arthritis of the SI joint can penetrate the muscle sheath of either muscle, producing an abscess of either the iliacus or psoas portion of the muscle.28 In addition, abscesses of the pelvis, retroperitoneal area, and abdomen can spread bacteria or fungi to local vertebral areas, causing spinal infections such as pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. From the lumbar spine, abscess formation may track along the psoas muscle and into the buttock (piriformis fossa), the perianal region, the groin, and even the popliteal fossa.29 Antalgic gait may develop with a psoas abscess secondary to a reflex spasm pulling the leg into internal rotation and causing a functional hip flexion contracture. The affected individual may have pain with hip extension. Often a tender mass can be palpated in the groin. The therapist must assess for TrPs of the iliopsoas muscle. A psoas minor syndrome can be mistaken for appendicitis so be sure and assess for TrPs.11 Four tests can be performed to assess the possibility of systemic origin of painful hip or thigh symptoms (Box 8-2). Gently pick up the client’s leg on the involved side and tap the heel. A painful expression and report of right lower quadrant pain may accompany peritoneal inflammation. If the client is willing and able, have him or her hop on one leg. The person with an inflamed peritoneum will clutch that side and be unable to complete the movement. The iliopsoas muscle test (Fig. 8-5) is performed when acute abdominal pain is a possible cause of hip or thigh pain. When an abscess forms on the iliopsoas muscle from an inflamed or perforated appendix or inflamed peritoneum, the iliopsoas muscle test causes pain felt in the right lower abdominal quadrant. (Pain and tenderness in the lower left side of the abdomen and pelvis may be caused by bowel perforation associated with diverticulitis, constipation, or obstipation [impaction] of the sigmoid, or appendicitis when the appendix is located on the left side of the midline.)

Screening for Gastrointestinal Disease

Signs and Symptoms of Gastrointestinal Disorders

Abdominal Pain

Primary Gastrointestinal Visceral Pain Patterns

Referred Gastrointestinal Pain Patterns

Dysphagia

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Epigastric Pain with Radiation

Early Satiety

Constipation

Diarrhea

Arthralgia

Shoulder Pain

Obturator or Psoas Abscess

Screening for Gastrointestinal Disease