Salvage of the Failed Darrach Procedure

Jeffrey A. Greenberg

William B. Kleinman

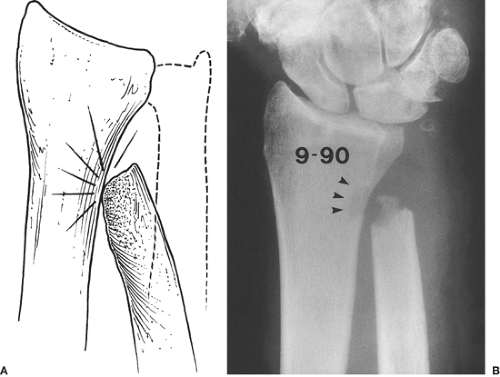

Excision of the entire distal ulna (seat, pole, and distal metaphysis) is a procedure used to decompress a painful ulnocarpal and distal radioulnar joints. By definition, the Darrach procedure (1) sacrifices the load-bearing seat of the ulna. Load transfer from the hand to the forearm passes through the seat, which also serves as the fulcrum for forearm rotation (2,3). Whereas many patients who have lower demands on their upper extremities do well functionally after Darrach resection, patients with higher demand can experience debilitating mechanical symptoms after removal of the distal ulna. Appropriate patient selection and meticulous intraoperative and postoperative care minimize the number of patients with poor clinical outcomes. Symptomatic radioulnar mechanical impingement (manifested by locking, catching, and erosion of the medial radial cortex) or excessive dorsal translational instability (“winging”) can occur nevertheless (4) (Fig. 33-1).

Salvage of the failed symptomatic Darrach resection is difficult. In addition to ulna-sided wrist pain and impaired hand function, secondary occupational and psychosocial hardships may develop (4,5). Many soft-tissue reconstructive procedures have been designed to overcome instability or impingement following resection of the distal ulna, but use of any of these procedures is difficult, particularly with respect to the availability of soft tissue for reconstruction.

If a Darrach resection of the distal ulna has been performed and fails, failure may be owing to a variety of causes, including excessive bony resection, insufficient soft-tissue structures remaining to tether the distal ulna stump, and postsurgical scarring or absence of usable bone and soft tissue. A variety of soft-tissue and bony procedures have been described in recent years, each directed at management of these complications (6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13).

After distal ulna resection, anatomic bony alignment of the two bones of the forearm through a full arc of pronosupination cannot be maintained. Impingement of the radiocarpal unit against the ulna can occur as the interosseous space is allowed to progressively narrow. Muscle forces crossing the interosseous space tend to accentuate convergence of the two forearm bones. After distal ulna resection, the pronator quadratus (PQ), normally a dynamic stabilizer of the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ), actually becomes a strong deforming force, propagating impingement. In addition, normal elasticity and the contractile force of the two first dorsal compartment tendons (which obliquely span the interosseous space from medial to lateral) contribute to radioulnar impingement in the absence of DRUJ bony stability. Finally, loss of the stabilizing effect of the triangular fibrocartilage complex and associated ulnocarpal soft-tissue stabilizers allows translation of the distal ulna with forearm rotation, promoting accentuated instability.

Clearly, symptomatic impingement following Darrach resection is a multifactorial problem caused by static loss of bone as well as soft-tissue elements, accentuated by dynamic muscular forces. To avoid the creation of a functionally devastating one-bone forearm, many creative reconstructive procedures have been devised in an attempt to alleviate symptoms. These options utilize tendon transfers (alone or in combination), osteotomies, capsuloplasties, and combinations of these procedures.

Our approach to the problem uses a two-tendon, three-component reconstruction developed by the senior author (14), which is successfully used to salvage that small percentage of failed Darrach resection patients seen in clinical practice who have post-Darrach symptomatic impingement or winging. The approach is specifically designed to address post-Darrach winging (dorsopalmar translational instability), as well as painful mechanical radioulnar impingement.

Technique

Approach the long, remaining proximal stump of the resected distal ulna through the interval between the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) and flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) tendons, along the line of the linea jugata.

Take care to preserve the periosteal sleeve along the medial border of the distal ulna.

Revise any irregularity or bony overgrowth of the end of the stump; remove any bony prominence that has developed while the ulna was impinging along the medial cortex of the radius. Maximal length, however, should be preserved.

Also remove any new bone that may have developed; it is essential to make certain that the entire DRUJ is decompressed.

Prepare the distal ulna stump for intramedullary reception of the split-ECU tendon transfer by reaming the medullary canal with a side-cutting burr.

Create an exit hole at the dorsomedial border, 1.5 cm proximal to the revised distal osteotomy (Fig. 33-2).

Harvest half of the ECU from proximal to distal, and leave it attached within the still intact sixth dorsal compartment fibro-osseous tunnel.

Harvest sufficient proximal length to allow the tendon to be passed into the medullary canal, out the exit hole, and back on itself in a woven fashion (Fig. 33-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree