Rheumatoid Rearfoot

Linnie V. Rabjohn

Daniel J. Yarmel

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an inflammatory, chronic condition that causes profound changes in the function and structure of the foot and ankle. Since the majority of disease manifestations commence in the forefoot, less literature is focused on symptomatology and treatment options for rearfoot abnormalities. Progression of the disease leads to a pronounced inflammation, deformity, and compromised function of the rearfoot, especially if conservative medical modalities are unable to control the disease.

This chapter does not focus on specific surgical techniques as these do not vary based on the presence of RA. Rather, one can review these specific surgical techniques in concomitant chapters of this textbook. Instead, this chapter reviews the specific changes noted in the rearfoot with disease progression and surgical considerations along with surgical options available to these patients. Certain considerations must be taken when proceeding with a rearfoot surgery in this population. A thorough understanding of the systemic changes noted to occur with RA is crucial for the foot and ankle surgeon. Bone composition and vascular and neurologic inadequacies along with muscular impairments can compromise the intraoperative and postoperative periods in a rheumatic patient. It is essential to carefully stage procedures and consider ambulatory status preoperatively as well as the change in weight-bearing status postoperatively. Often, the upper extremity involvement can preclude the use of ambulatory assisting devices. If multiple surgical corrections are necessary, one must perform them in such an order as to maximize benefit to the patient from an orthopaedic standpoint.

The progression of this disease through the rearfoot does vary and should be evaluated on an individual basis. There are, however, patterns of involvement at certain stages of the disease that must be recognized. The full evaluation of progression is a lifelong process that can involve many medical, radiographic, and surgical modalities. Radiographic and clinical modalities can be used as both diagnostic and prognostic tools in RA. Serial radiographs are an excellent tool to monitor the progression of RA.

Certain structural changes are characteristic with RA involving the rearfoot, such as pes planovalgus. Gait analysis early in the diagnosis of the disease shows changes consistent with pes planovalgus long before this deformity is noted clinically. As any deformity with RA progresses, a physician must be cognizant of the essential joints in the rearfoot complex, the talonavicular (TN), calcaneocuboid, subtalar, and tibiotalar. Each joint must be inspected prior to rearfoot procedures to avoid an otherwise unnecessary arthrodesis in the patient’s future. Soft tissue structures, such as tendon, capsule, and bursa, are affected by RA with a chronic synovitis. This synovitis leads to deformity and functional impairments. The physician must remember that RA is not strictly an articular disease and often involves structures that are not associated directly with joints.

The goals of surgery for an RA patient do not differ greatly than the goals for those who are not afflicted with the disease. The goals include relieving pain and improving function. For an RA patient, surgical choices tend to involve forms of synovectomy, arthrodesis, and joint replacement. This does not stray from surgical concepts in the forefoot. As the evolution of surgical techniques and internal hardware advances, so do the treatment options for the rearfoot. Recent advances in total ankle replacement (TAR), intramedullary (IM) nails, and external fixation has allowed the introduction of new surgical choices to RA patients. Ultimately, the goal is not to achieve anatomical reconstruction; rather it is to obtain a plantigrade, nonpainful foot and ankle.

CONSIDERATIONS

Many considerations must be taken into account in the process of determining surgical eligibility in an RA patient. Preoperative assessment is crucial to identify potential complications that can occur, specifically with this disease and its treatments. A whole-patient approach with multidisciplinary involvement is needed to prepare the patient for surgery. This is evident with the commonly associated alantoaxial cervical damage in RA. This damage has been linked to changes in peripheral small joints. If this spinal change is unobserved, it can lead to devastating consequences (1).

The goals of surgery for RA patients are different than those of a normal, healthy patient. Even the smallest procedure that may appear as inconsequential in the non-RA patient may yield great benefit to the rheumatoid patient (2). Depending on the deformity and prognosis of the disease state, surgical procedures may need to be performed earlier and more aggressively in RA patients.

Clinical and radiographic evidence, as well as quantitative laboratory values, help determine the progression, aggressiveness, and prognosis for patients with RA. Rheumatoid factor (RF) appears to be a predictor of erosive damage (3). Seropositive patients with high RF progress twice as fast in their Larsen score, a radiographic analysis of RA, than patients who are seronegative (4). Initial high levels of RF predict rapid deterioration of joints radiographically, even in patients receiving

conventional treatment (3). Seropositive patients who are in need of aggressive antierosion treatments are at a higher risk of requiring rearfoot surgery for progressive symptomatology. Like RF, C-reactive protein (CRP) is also a predictor of erosive damage. Aggressive drug treatment in patients with elevated CRP reduces the rate of radiographic progression (5,6).

conventional treatment (3). Seropositive patients who are in need of aggressive antierosion treatments are at a higher risk of requiring rearfoot surgery for progressive symptomatology. Like RF, C-reactive protein (CRP) is also a predictor of erosive damage. Aggressive drug treatment in patients with elevated CRP reduces the rate of radiographic progression (5,6).

RA is a chronic wasting disease. Higher energy expenditure was found in patients with chronic inflammation even if the disease was well controlled clinically (7). Furthermore, sustained inflammation is found to be inversely related to survival. Better clinical outcomes are associated with maintaining a lower level of chronic inflammation.

Three-dimensional (3-D) gait analysis is used to determine the effects of RA on foot and ankle function, impairment, and disability (8). The deleterious effects of this disease occur early in the course of progression. There is a moderate to high foot impairment and related disability noted in RA patients with disease duration of less than 2 years. Patients with early RA walk with a slower gait and have a longer double support phase when compared with controls (8,9). Also common among these patients is a lower calcaneal inclination angle, a lower medial arch height, and a greater peak eversion in stance and lower peak ankle plantarflexion. Pressure analysis shows a reduced toe contact area, elevated forefoot pressure, and a larger midfoot contact area. Kinematic studies show that RA patients have a generalized decreased range of motion in multiple foot and ankle joints (AJs) throughout the gait cycle (9). A decreased range of motion was found not only in the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) but also in all three planes of hindfoot motion. RA patients have a significantly higher report of decreased mobility and decreased ability to perform activities of daily living when compared with a general population of patients with end-stage ankle arthritis (10).

Preoperative planning is vital for determining the appropriate order in which surgery should be performed to allow maximum benefit for the patient. If both forefoot surgery and rearfoot surgery are needed, it may be more advantageous to perform the forefoot surgery first and observe the rearfoot compensation postoperatively (2). If larger joints, such as the hip or knee, are also in need of surgical correction, the forefoot procedures should be performed prior to these. This will allow for pain-free ambulation during the postoperative larger joint rehabilitation period. After the larger joint rehabilitation, the physician could proceed with any needed rearfoot procedures.

Synovial inflammation characteristic with RA causes an accelerated regional periarticular osteopenia, which affects the composition of bone (2,11). This osteopenia is of concern when determining procedure types and fixation techniques. Global osteopenia, in an RA patient, can be associated with the use of certain treatment medications, as well as age, sex, and the decreased stress on the bones due to low physical activity. Methotrexate, commonly used to treat systemic manifestations of RA, has been reported to cause an increased incidence of fractures, associating its use with osseous compromise (12,13).

Fixation is largely dependent upon procedure and bone composition. Screw fixation in a patient with RA may necessitate engaging cortex with the threads of the screw to allow for more stability (2). One example of this would be fixating a subtalar joint (STJ) arthrodesis with a screw placed from the anterior talar neck to posterior, inferior calcaneus engaging the lateral wall of the calcaneus. It is important to countersink properly if the bone is of sufficient density. If screw compression fails to provide adequate rigid fixation, the surgeon may need to apply alternative options, such as axially oriented Kirschner wires (K-wires) (0.062 inches or greater) or Steinmann pins (2). Threaded pins and wires, over smooth, provide more protection against migration in compromised bone. External fixation is an alternative if the bone composition inhibits reliable internal fixation. For external fixation devices, the pins should be perpendicular to the vector of compression to limit migration.

Indications for arthrodesis of a rearfoot joint in an RA patient include pain in the presence of aggressive, unsuccessful medical therapy, loss of function due to deformity or instability, a poor prognosis of a specific joint even in the absence of pain and deformity, and failed total joint arthroplasty (2). Consideration of arthrodesis should not fail to include the ramifications of the postoperative course on a patient with RA. Often, an arthrodesis or extensive rearfoot surgical procedure means spending at least 6 to 8 weeks non-weight-bearing, which for a patient who already has limited function and possible upper extremity involvement could be difficult. Close evaluation of the involvement of the wrists, metacarpophalangeal joints, elbows, and shoulders must be done prior to the decision to proceed with a rearfoot surgery. One must also consider the strength present in the patient’s upper extremity and determine if it is sufficient to support the body during transfers if non-weight-bearing. It is important to minimize the debilitation associated with a long period of non-weight-bearing, without compromising surgical success (14). Certain fixation techniques, discussed later in this chapter, may afford for earlier weight-bearing. However, caution is recommended when patients are allowed to weight-bear early as this may harm the surgical site.

In 20% to 35% of patients with RA, subcutaneous nodules develop as the disease progresses (11). These nodules are referred to as rheumatoid nodules and develop at either periarticular or high-pressure areas. Conservative methods to alleviate the nodules include off-loading the area and accommodative padding. Surgical intervention is needed if the nodules become symptomatic or infected. The nodules are nonencapsulated, making surgical dissection difficult. Recurrence of RA nodules is common after excision. When considering any surgical incision, an RA nodule should be avoided if active.

It is necessary to evaluate the presence and extent of arterial and venous disease, commonly associated with RA. Peripheral vascular disease can go undiagnosed in patients with RA. A diagnosis of exercise-induced ischemia is difficult to deduce due to the potential sedentary lifestyle of these patients. Even if the claudication-type symptoms are present, they can be mistaken for articular pain (15,16). Long-term steroid treatment is associated with a hypercoagulable state. This enhances the development of atherosclerosis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus (17). Systemic inflammation, associated with RA, also predisposes a patient to a thickened intimal layer that can lead to atherosclerosis (18). This is a concern for both the development of complications associated with surgery, such as increased morbidity, as well as more specific postoperative healing ability.

The extent of the peripheral arterial impairment is unknown. With this in mind, simple noninvasive arterial tests should be performed prior to proceeding with any rearfoot surgery. An ankle brachial index (ABI) is a noninvasive, simple test that can help identify vascular compromise. Pulse wave analysis has revealed an increased vascular resistance in RA along with arterial stiffness. Arterial incompressibility, termed Monckeberg sclerosis, is characterized by medial arterial calcification.

This is also found in RA and can falsely elevate ABI. The association between joint damage and arterial incompressibility may be linked to a common deficiency of osteoprotegerin or a related mediator of osteoclasts and calcium metabolism.

This is also found in RA and can falsely elevate ABI. The association between joint damage and arterial incompressibility may be linked to a common deficiency of osteoprotegerin or a related mediator of osteoclasts and calcium metabolism.

Presence of vasculitis may compromise healing (14). Vasculitis has also been tagged as a potential, but uncommon, manifestation of RA characterized by erosive articular changes, rheumatoid nodules, high levels of RF, and presence of cryoglobulins (19). This vascular condition has also been identified as a precursor in the development of neuropathy.

RA has been identified with a higher risk for thromboembolic events following foot and ankle surgery (20). Yet Hanslow et al failed to show an association between the development of deep vein thrombosis and the type of surgery being performed. However, previous risk factors have been shown to increase incidence further and these include the tourniquet time, hindfoot surgery, and advancing age (21). Therefore, with consideration of rearfoot surgery in an RA patient, the surgeon must determine the risk:benefit ratio of tourniquet usage and apply appropriate countermeasures postoperatively. These measures would include early ambulation, graduated compression stockings, or use of an anticoagulant agent.

Peripheral sensory neuropathy can occur in RA patients (22). The frequency, pattern, and associated disability secondary to neuropathy are highly variable (23). There are no definitive criteria for assessment of this patient population. Almost one-third of the RA patients evaluated in one study were found to have peripheral neuropathy with the most common form being sensory neuropathy. In males, the neuropathy was demyelinating, and in females, axonal in nature. The presence of different forms of sensory neuropathy suggests that other mechanisms besides vasculitis of the vasa nervorum are at work. Certain medications can be responsible for the development of peripheral neuropathy in RA patients (19). Infliximab is one of several medications linked to the development of a demyelinating neuropathy. Other medications include leflunomide, gold salts, and methotrexate (24). Age is the most reliable independent factor influencing presence of neuropathy, and the probability of developing neuropathy increases steadily after the age of 50. The presence of articular erosions is also associated with a fourfold increase in the risk of developing peripheral neuropathy. Mononeuritis multiplex is an asymmetric sensory and motor neuropathy that is painful and involves at least two separate nerve areas of the body (19). As with any peripheral sensory neuropathy, Charcot osteoarthropathy is a possible manifestation. Close neurologic and radiographic monitoring should be performed on all RA patients.

Conservative treatment options to manage rearfoot deformity, instability, or pain secondary to RA are often limited to use in the early stages of the disease course in which synovitis predominates. Medical treatment for an RA patient is directed toward reduction of pain and control of inflammation (14). These medication regimens may include oral steroids and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Other conservative options for an RA patient, specific to the foot and ankle, include functional and accommodative inserts, custom shoes, steroid injections, and physical therapy to reduce joint stiffness (11,14). If mild symptoms are present, a localized water-soluble steroid injection may be beneficial to the patient (25). When end-stage deformities develop and symptoms coexist, conservative measures are not enough and aggressive surgical intervention may be needed (14).

REARFOOT PROGRESSION OF DISEASE

In the realm of rheumatic diseases, RA is the second most common, next to osteoarthritis, but has the most deleterious effect on joints (26). The exact course of RA and the disease progression of the hindfoot are unclear. The expression and course of RA is variable involving marked synovial proliferation with pain and swelling or progressive loss of articular cartilage and joint space (14).

Early in the progression of disease, inflammatory processes are predominant and lead to disability (8). Pain and stiffness in the foot and ankle are the initial symptoms in almost half of patients. The forefoot symptoms usually develop over several days or weeks, but it may take years for rearfoot manifestations (27). In patients with disease duration of less than 5 years, only 8% have rearfoot pain (28). However, in the next several years, the report of rearfoot pain steadily increases. A quarter to one-third of patients report rearfoot pain, with a duration of disease greater than 5 years (29). It has been hypothesized that peritalar disease usually occurs after 5 years of disease progression; however, there is evidence that the synovitis does occur earlier. In the later stages of RA, structural abnormalities lead to the functional impairment (8).

Young-onset RA occurs in middle-aged individuals. These patients have a greater involvement of proximal interphalangeal, metacarpophalangeal, elbow, metatarsophalangeal, and ankle joints (30). The incidence of severe deformity is lower in young-onset RA. These patients tend to have stiff joints. Adult-onset RA begins in patients over the age of 60 and is associated with the more serious deformities and instabilities (2,30). Around 2% of the geriatric population is affected by this inflammatory arthritis (31).

The most frequent involvement occurs in the forefoot at the MTPJ in comparison to the midfoot and rearfoot areas (32). Lisfranc’s involvement is uncommon and typically does not necessitate surgery (14). The AJ is the least affected weightbearing joint and the STJ is one of the most frequently involved joints (33). Progression of joint involvement can be determined through radiographic interpretation. Belt et al (34) evaluated radiographs of RA patients to determine the relationship between ankle and subtalar destruction. STJ pathology usually precedes radiographic changes in the AJ in the course of RA. Significant STJ involvement is observed an average of 5 to 7 years before AJ changes are observed. Studies concluded that the ankle is involved late in the disease and usually only affects patients with severe RA (34,35). They determined that radiographic changes in the ankle are secondary to stresses resulting from abnormal alignment of the STJ.

RADIOGRAPHIC AND IMAGING MODALITIES

Radiographs remain the appropriate choice for establishing a diagnosis of RA, as well as tracking the progression of the disease and determining the efficacy of treatment. In addition, other imaging modalities are available to assist in the diagnosis of the early changes seen with RA that may not be evident on plain radiographs. These modalities allow for the evaluation of soft tissue involvement. Both MRI and ultrasound are noninvasive studies that can help distinguish the accurate involvement of synovitis in soft tissue and tendons, bursal changes, and osseous articular changes.

Radiographic modalities can be used to track the progression or regression of a disease as well as confirm or establish an appropriate diagnosis (36). A diagnosis can be supported for an articular disorder, such as RA, based on the pattern of joint involvement through consecutive radiographic findings. However, early RA radiographic changes are not always recognized and can be nonspecific, making an early diagnosis difficult with radiographs alone (27). Early changes consist more of soft tissue swelling and periarticular osteopenia. With disease progression, synovitis leads to the characteristic marginal erosions at the junction of the synovium and cartilage. However, once radiographic changes start, there is relatively rapid advancement (3,37). These findings include the following: marginal erosions that can progress to involve the central aspect of the joint, subluxations, periarticular soft tissue edema secondary to synovitis, osteoporosis, articular narrowing, and fibrous ankylosis (36,38). With advanced RA, symmetrical cartilage loss continues with secondary osteoarthritic changes such as the presence of osteophytes and subchondral sclerosis (Fig. 62.1) (27). In following the radiographic parameters, a physician can closely monitor the progression of disease as well as track the efficacy of treatment (3).

In RA, radiographic changes are more common in the foot than the hand, making it important for foot and ankle surgeons to evaluate possible prognosis through lower extremity plain films (39). In literature, attention has focused mainly on forefoot radiographic changes with less consideration on radiographic analysis of the midfoot and rearfoot. Serial measurements of radiographic changes are necessary to determine rate of progression over time (3). With evidence of rapid radiographic progression, a treatment regimen should be more aggressive. There appears to be a direct relationship between increased Larsen score and the duration of the disease. The Larsen score is a method of calculating the severity of articular damage caused by RA based on radiographs. A physician should understand that although healing can be identified on radiographs, it does not always occur. Radiographic parameters for healing include erosion recortication and new bone growth within erosions.

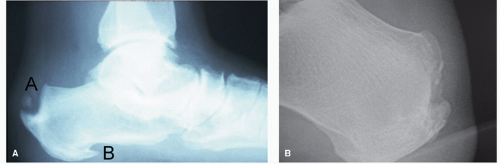

Rearfoot and midfoot abnormalities are not as characteristic as those seen in the forefoot. Some of the more common manifestations seen include the following: STJ sclerosis, articular narrowing, osseous changes consistent with pes planovalgus, fibular stress fractures, and retrocalcaneal bursitis (14,36). Persistent synovitis can lead to osseous destruction, which on radiographs appears as joint space narrowing and erosions (40). Changes at the level of the calcaneus, which may indicate rheumatoid involvement, include enthesiopathies and erosions (Fig. 62.2A). The areas of the calcaneus commonly involved are the posterior-superior surface of the retrocalcaneal bursa, posterior surface above the Achilles tendon insertion, plantar surface at the insertion of the plantar fascia, and the long plantar ligament (Fig. 62.2B).

The midtarsal joints more commonly reveal radiographic changes than clinical symptoms, while the AJ is more likely to exhibit clinical symptoms than radiographic changes (14). As RA progresses, the TN joint usually initiates the first radiographic changes in comparison to the other midfoot and rearfoot joints (2).

Ultrasonography is a noninvasive, valuable imaging modality in the recognition of tendon involvement and joint damage (25,41,42). Ultrasound-guided corticosteroid injections improve efficacy of this recognized form of treatment in RA (25,43). Clinical judgment of the location of involved tissues has been shown to be misleading, supporting the need for additional diagnostic modalities, such as ultrasound (25). For example, often what is clinically perceived as posterior tibialis or peroneal tendon involvement may actually be STJ pathology. In a study designed to evaluate clinical judgment alone versus clinical judgment with ultrasound imaging to determine placement of corticosteroid injections, it was found that the injection location was corrected for 56 out of 68 patients with ultrasound

imaging (25). Of the injections given, 58% were for the cunieonavicular joint, 36% for the calcaneocuboid joint, and 35% for the STJ, implying that involvement of these joints may be clinically underestimated.

imaging (25). Of the injections given, 58% were for the cunieonavicular joint, 36% for the calcaneocuboid joint, and 35% for the STJ, implying that involvement of these joints may be clinically underestimated.

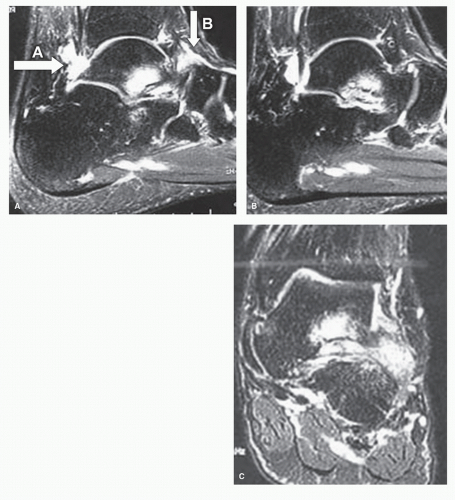

Currently, radiographs remain the most appropriate modality to evaluate progression of disease but are limited in the evaluation of soft tissue pathology (3). Also, the detection of the degree of inflammation present can be underestimated by clinical interpretation and radiographs alone (44,45). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is advantageous for advanced soft tissue and articular evaluation in RA. On MRI, the amount of fluid actually present in the joint effusions is often smaller than on clinical exam. This is because the joint becomes distended by the synovial pannus (38). The inflamed synovial pannus, in the smaller pedal joints, will create outpouchings that appear as ganglia containing complex material. The synovium is responsible for the erosive changes characteristic in RA. MRIs demonstrate this phenomenon occurring at the capsular margin, in which the synovium comes into contact with bone and becomes unprotected by cartilage (Fig. 62.3A). On MRI, these

lesions appear as a thin rim of subchondral marrow edema and enhancement on T2 images (Fig. 62.3B and C). A common MRI finding in an RA-affected AJ is erosion in the distal syndesmotic recess.

lesions appear as a thin rim of subchondral marrow edema and enhancement on T2 images (Fig. 62.3B and C). A common MRI finding in an RA-affected AJ is erosion in the distal syndesmotic recess.

MRI evaluation of the bursae is important due to the inflammation of the synovial tissue within the bursae (38). As mentioned previously, the retrocalcaneal bursa is often involved with RA. When involved, this bursa will become distended with pannus and will appear as a high signal on T2 images. Adjacent to this bursa, the superior calcaneus can reveal erosions secondary to the synovial pannus along with effects on the Achilles tendon. The Achilles tendon often becomes attenuated at the area of the retrocalcaneal bursa. Less commonly a bursa, inflamed with synovium, is noted at the insertion of the plantar fascia.

Tendons also fall subject to synovitis related to RA. MRI allows evaluation of the tendon sheath to identify the presence of fluid representing proliferative synovium (38). Gadoliniumenhanced MRI can be used to determine the presence of tenosynovitis (46). With the close proximity of the posterior tibial and peroneal tendons to hind foot joints, MRI can be useful in distinguishing the true pathology.

PES PLANOVALGUS

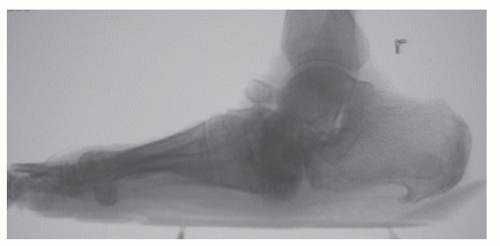

Pes planovalgus is a recognized characteristic in the RA population, reported at an incidence of 46% to 67% (Fig. 62.4) (29,47,48,49,50 and 51). Structurally, this is described as a collapse of the medial longitudinal arch and valgus deformity of the rearfoot (29,52,53). The development of pes planovalgus associated with RA results from gradual muscle weaknesses and imbalances, as well as ligamentous laxity caused by persistent and repeated inflammatory episodes (54). The function of the tibialis posterior tendon is essential in maintaining normal architecture of the foot (55). With RA inflammatory synovitis, this tendon becomes vulnerable to weakening and structural damage.

Equinus, caused by gastrocnemius contracture, is common in RA and leads to an increase in forefoot pressures (55). In an attempt to compensate for a collapsed medial column, the posterior tibial tendon weakens secondary to the increased demand, and hyperpronation develops (46,55). This, coupled with inflammatory synovitis of the posterior tibial tendon and RA involvement of the peritalar joints, allows for the instability of the STJ that ultimately results in a valgus deformity (46,56). The tenosynovitis of the posterior tibial tendon may be a result of ankle synovitis (46). As synovitis advances through the AJ, it can perforate the joint capsule, involving the adjacent joint structures.

Figure 62.4 Lateral radiograph demonstrating collapse of the TN, calcaneocuboid, and STJ in an RA patient with severe pes planovalgus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|