Dallas Kingsbury

David Bressler

![]()

25: Rheumatoid Arthritis

![]()

PATIENT CARE

GOALS

Evaluate and develop a rehabilitative plan of care that is compassionate, effective, and targeted at the individual patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

OBJECTIVES

1. Perform a detailed history and physical examination of a patient with RA.

2. Identify the key components of a rehabilitation program as they relate to the rheumatoid patient with RA.

3. Identify the psychosocial and vocational implications for the patient with RA and strategies to address them.

4. Formulate a sample rehabilitation treatment plan for the patient with RA.

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL

The history and physical examination in patients with either suspected or confirmed RA should reflect the understanding that it is an autoimmune disease primarily of the joints, with an array of possible comorbid systemic conditions. Areas of the patient history that are notably important for diagnosing and characterizing RA include the number and site of involved joints, as well as the duration of symptoms, as these questions are directly part of the diagnostic criteria. Especially at the onset, RA may be difficult to differentiate from other immune-mediated diseases. It may coexist with other rheumatologic diseases, such as mixed connective tissue disease and overlap syndrome, or the symptoms may be fleeting as in palindromic rheumatism. RA classically affects joints symmetrically, and more than other rheumatic disorders, it has a preference for small joints of the hands and feet. Protracted morning stiffness is a hallmark of the disease. Extraarticular manifestations of RA are common, with cardiac, pulmonary, integumentary, and hematologic systems being most affected (1).

Rheumatoid nodules are painless, firm areas of swelling of subcutaneous tissue, typically found on the extensor surfaces of the limbs (i.e., olecranon, dorsal hand at metacarpophalangeal [MCP] joints). Histologically, the nodules are comprised of a center of fibrinoid necrosis surrounded by a fibrous tissue shell, the larger of which can be multiloculated and contain synovial fluid. The appearance of rheumatoid nodules portends a poor prognosis and a sign of heightened disease activity.

The physical examination must be organized to include articular and extraarticular manifestations. As the patient transitions through the natural history of the disease, joint pathology will change over time. Fortunately, due to earlier diagnosis and earlier initiation of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) and biologic therapy, many of the debilitating, latestage manifestations of RA are becoming less frequent. Initially, joint swelling and tenderness may appear similar to other forms of arthritis. Palpation can differentiate between the bogginess of synovial edema in RA from the bony osteophytes of osteoarthritis (OA). Periarticular edema is more common in gout, while the rheumatoid joint will have swelling confined to the capsule. As the disease progresses, abnormal synovium can proliferate and migrate across articular cartilage into the joint capsule or surrounding tendons. This boggy mass of synovium laden with inflammatory mediators is called a pannus.

The wrist is the most commonly affected joint in up to 75% of RA patients (2), with synovitis progressively weakening the ligaments between the radius, ulna, and carpal bones. One area to focus is the scapholunate ligament, assessing for laxity or subluxation, since compromise of this area leads to a cascade of events in which the radial support structures collapse, volar subluxation of the radius occurs, the metacarpals deviate radially, and the fingers deviate in an ulnar direction (3). Chronic synovitis of the MCP joints accentuates the ulnar drift of the fingers. Finger deformities are also very common in RA. One of the earliest physical findings is proximal interphalangeal joint edema, with tendon and ligament weakening or rupture occurring after many years of active disease. The two major late findings at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint include the boutonnière deformity and swan-neck deformity. With a boutonnière deformity, the PIP is set into flexion, with reciprocal extension of the MCP and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. Synovial inflammation leads to a rupture of the extensor hood and causes the lateral bands to migrate downward, causing PIP flexion and DIP hyperextension. The swan-neck deformity is a hyperextension at the PIP joint, with MCP and DIP joint flexion. It can occur from multiple combinations of joint disruptions, which usually involve PIP volar support loss (e.g., volar plate rupture) and eventual contracture of the hand intrinsic muscles. In the upper extremity, elbow synovitis can lead to loss of extension and sometimes a compressive ulnar neuropathy. Shoulder and hip involvement is less common than the more distal joints, and typically occurs later in the disease process. Painful synovitis can lead to loss of range of motion (ROM) and joint contractures.

In the lower extremity, knee effusions are common and can sometimes lead to joint contracture. At the ankle, synovitis typically affects the tibiotalar joint. Synovial proliferation can extend to the tarsal tunnel or involve the posterior tibialis tendon resulting in a tenosynovitis and possible tendon rupture. Similar to the hand, chronic synovitis can cause weakening of the delicate ligamentous structures in the forefoot, at first leading to metatarsophalangeal (MTP) edema, tenderness, dorsal subluxation, and hallux valgus deformity. As noted, the painful metatarsal subluxation is caused by distention of the joint capsule, with the PIP joints moving superiorly, causing hammer toe deformities. The hip is one of the last joints to be involved in adult RA (but, paradoxically, is involved early in JRA). Remodeling of the acetabulum from chronic synovitis can result in “protrusio acetabuli,” in which the femoral head migrates deeply into the acetabulum. The definitive treatment is total hip arthroplasty.

The spine is not frequently involved, with the notable exception of the atlantoaxial joint. Rupture of the transverse ligament between C1 and C2 can lead to myelopathy and possible death due to migration of the odontoid into the brainstem. It is important to obtain lateral, flexion/extension, and open mouth views, since an anterior subluxation of 9 mm or more between C1 and C2 increases the risk for cord compression (4). In advanced disease, atlantoaxial involvement becomes more of a concern, considering that up to 60% of RA patients who needed hip or knee arthroplasty were found to have cervical spine instability on radiographic screening (5) (Box 25.1).

FUNCTIONAL ASSESSMENT

A rehabilitation approach to RA should include an inventory of the patient’s daily activities. This will allow the physiatrist to tailor a patient-specific rehabilitation program, as opposed to relying on a generic template. Two patients with similar severities of ulnar deviations and boutonnière deformities may compensate differently for manual tasks, and therefore may require separate rehabilitation approaches. Questions to ask include the following: Can you dress yourself? Get in/out of bed? Walk outdoors on flat ground? Wash/dry your entire body? Bend down to pick up clothing from the floor? Turn faucets on/off? Get in/out of the car?

Box 25.1 Pearl: Atlantoaxial instability

Cervical spine disease (C1–C2) parallels peripheral joint disease

Cervical spine disease (C1–C2) parallels peripheral joint disease

Box 25.2 Functional Classification

Class I: no functional limitations

Class I: no functional limitations

Class II: joint discomfort or limitations in ROM, but activities of daily living (ADLs) not significantly compromised

Class II: joint discomfort or limitations in ROM, but activities of daily living (ADLs) not significantly compromised

Class III: ADLs significantly compromised

Class III: ADLs significantly compromised

Class IV: incapacitated, and unable to perform ADLs

Class IV: incapacitated, and unable to perform ADLs

Box 25.3 Pearl: Disease Activity Index

Functional status is most traditionally assessed by the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ)

Functional status is most traditionally assessed by the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ)

Based on American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines (6), patients can be given a functional classification, from I to IV increasing in severity of disability (Boxes 25.2, 25.3).

REHABILITATION PROGRAM

Historically, any exercise for RA was controversial, but now therapeutic exercise is considered a basic component of any comprehensive rehabilitation program. Areas that have shown notable success include aerobic exercise, strengthening exercises, cognitive behavioral therapy, and self-efficacy training. Joint and energy conservation, adaptive equipment, and orthotic support are the basic tenets of a comprehensive occupational therapy program (7).

In RA patients, short-term (less than 3 months) land- or water-based dynamic exercise programs have a positive effect on aerobic capacity, muscle strength, and functional ability (8). Low-impact activities, such as swimming and biking, are preferred. One study directly compared land-based aerobic capacity training (walking) with water-based aerobic capacity training, and found no differences with regard to safety (9). Overall, studies have shown decreased inflammation, joint pain, and joint tenderness (10). Specifically for aerobic exercises (at 50%–90% maximum heart rate [HR]), a meta-analysis of 14 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed small, beneficial effects on cardiorespiratory function, functional ability, and disease activity (11).

For ROM therapy and stretching, it is recommended that each joint is moved through its complete ROM at least once daily. Joint movement is gently encouraged despite pain, and it needs to be emphasized that ROM therapy is not done to relieve pain, but to prevent contractures. All types of strengthening exercises may be employed, as long as they do not result in muscle soreness greater than 2 hours post exercise, or fatigue lasting more than 1 hour after exercise, or increased joint pain noted during exercise. Initially isometrics can be employed due to decreased dynamic/sheer forces on the joints compared to isotonic and isokinetic training.

Modalities can also assist in physical and occupational therapy programs. Cold therapy is ideal for acute flares, especially in joints with effusions. Deep heat is indicated for patients with chronic inflammation and contractures (Box 25.4).

HOW SHOULD THE REHABILITATION PROGRAM BE MODIFIED DURING A FLARE?

In a word, rest! Reevaluate and reduce all resistive exercises, especially those that stress the small joints of the hands and feet. In this case, splinting is helpful to ensure that joint stress is minimized. Limited passive ROM is performed to prevent contracture. Medically, flares often require steroid supplementation, in addition to considering a change in DMARD therapy (Box 25.5).

PAIN MANAGEMENT

Patients often come to the physiatrist, either directly or from another consulting physician, with the expectation of complete pain relief. The first step is explaining that complete pain relief is often unachievable. A reasonable goal is pain reduction sufficient enough to allow greater participation in activities of daily living (ADLs) (Box 25.6).

Box 25.4 Pearl: Exercise Precautions

Caution when ordering isometric exercise (especially in the upper extremity)

Caution when ordering isometric exercise (especially in the upper extremity)

Sustained isometric contractions increase intrathoracic pressure and decrease cardiac output (Valsalva effect). To compensate, heart rate and vasoconstriction occur to maintain blood pressure and cardiac output

Sustained isometric contractions increase intrathoracic pressure and decrease cardiac output (Valsalva effect). To compensate, heart rate and vasoconstriction occur to maintain blood pressure and cardiac output

Rheumatoid arthritis patients frequently have hypertension and/or cardiovascular disease, and patients with impaired hemodynamics may respond to isometric exercises with exaggerated or dangerous increases in blood pressure

Rheumatoid arthritis patients frequently have hypertension and/or cardiovascular disease, and patients with impaired hemodynamics may respond to isometric exercises with exaggerated or dangerous increases in blood pressure

High-risk cardiac patients should be monitored closely for chest pain, abnormal BP elevations, and arrhythmias (12)

High-risk cardiac patients should be monitored closely for chest pain, abnormal BP elevations, and arrhythmias (12)

Box 25.5 Pearl: Exercise Prescription Modification Should Be Considered in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients With:

Fatigue lasting greater than 1 hour post exercise

Fatigue lasting greater than 1 hour post exercise

Muscle soreness lasting greater than 2 hours post exercise

Muscle soreness lasting greater than 2 hours post exercise

Increased joint pain during exercise

Increased joint pain during exercise

Box 25.6 Sample Rehabilitation Prescription

Diagnosis: Rheumatoid arthritis

Diagnosis: Rheumatoid arthritis

ICD-9 Code: 714.0

ICD-9 Code: 714.0

Impairment: decreased ROM right MCP and PIP joints; right knee 20° flexion contracture, decreased muscle strength in all 4 extremities

Impairment: decreased ROM right MCP and PIP joints; right knee 20° flexion contracture, decreased muscle strength in all 4 extremities

Disability: decreased ambulation, decreased ADLs

Disability: decreased ambulation, decreased ADLs

Precautions: avoid Valsalva maneuver, do not overfatigue, postexercise pain not greater than 2 hours, contact MD if acute flare

Precautions: avoid Valsalva maneuver, do not overfatigue, postexercise pain not greater than 2 hours, contact MD if acute flare

Goals: pain relief, inflammation reduction, joint preservation, functional restoration

Goals: pain relief, inflammation reduction, joint preservation, functional restoration

Modalities: cryotherapy for acute flares, paraffin/fluidotherapy for the hands, orthotic splinting as needed, deep heating for joint contracture and stiffness

Modalities: cryotherapy for acute flares, paraffin/fluidotherapy for the hands, orthotic splinting as needed, deep heating for joint contracture and stiffness

PT/OT: ROM, mobilization to affected joints, stretching (after preheating, if contractures), strengthening exercises (especially closed-chain), light isotonics, isometrics (only for acute flare), general conditioning exercises (aerobics), cross training using low-impact exercise (cycling, swimming), gait training with appropriate assistive device, ADL evaluation and training, adaptive equipment and training, joint protection, and energy-conservation techniques, home exercise program

PT/OT: ROM, mobilization to affected joints, stretching (after preheating, if contractures), strengthening exercises (especially closed-chain), light isotonics, isometrics (only for acute flare), general conditioning exercises (aerobics), cross training using low-impact exercise (cycling, swimming), gait training with appropriate assistive device, ADL evaluation and training, adaptive equipment and training, joint protection, and energy-conservation techniques, home exercise program

MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

GOALS

Demonstrate knowledge of established evidence-based and evolving biomedical, clinical epidemiological, and sociobehavioral sciences pertaining to RA, as well as the application of this knowledge to guide holistic patient care.

OBJECTIVES

1. Define RA, and describe the epidemiology, natural history, and pathophysiology of the disease.

2. Describe how RA is diagnosed and what treatment options are available.

3. Review the range of prognoses associated with RA depending on severity and risk factors.

4. Educate patients on making patient-centered decisions regarding their plans of care.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

RA is a symmetric, systemic, autoimmune, polyarthritis caused by abnormal growth of inflammatory synovial tissue, resulting in cartilage destruction and surrounding bone erosion. The worldwide prevalence is approximately 1%, annual incidence is about 3/10,000 adults, and it is two to three times more common in women (13). This incidence has remained stable over many years. New criteria for diagnosing early RA were published in 2010, and follow-up studies estimating incidence rates using the new criteria have yielded similar results (14). The etiology of RA remains unknown, but is considered to be multifactorial, resulting from an interaction between a genetic predisposition and environmental exposure, the exact contributions of which are still being elucidated. The important genetic contributors are major histocompatibility genes (mostly HLA-DRB1), in addition to minor immunomodulation genes. Environmental associations include alcohol, tobacco (increases susceptibility up to 20- to 40-fold), and even oral cavity flora (15).

The latest theories cite that preclinical RA likely develops via an immunologic conflict, unintuitively outside the joints or synovial membrane, in the mucous membranes of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract or airways. Subsequently, upon exposure to a second event, the autoimmune process spreads to the synovium, with eventual systemic involvement, giving rise to typical RA symptoms and signs. The “second event” is still being investigated (16). The hallmark of this disease is “synovitis,” that is, a joint synovium laden with autoantibodies, several classes of leukocytes, and inflammatory cytokines that initially cause joint pain and stiffness. Over time, this synovitis causes diffuse systemic manifestations, in addition to the hallmarks of joint and bone destruction.

NATURAL HISTORY

Stage 1 is characterized by morning fatigue and joint stiffness, and lasts for several weeks to 2 months. Joint pain is primarily localized to the hands and wrists, which may begin to show signs of edema. At this point, no deformities or rheumatoid nodules are present, serological rheumatoid factor (RF) titers are usually negative, and there is no synovial proliferation on pathological or physical examination.

By the time a patient enters stage 2, the diagnosis of RA has been established, and 70% have a detectible RF titer. An experienced clinician may be able to appreciate palpable proliferative synovium surrounding affected joints. Radiographically, x-rays will show early diffuse juxtaarticular osteopenia but there is not yet evidence of erosions.

If treatment is not initiated, patients may enter stage 3, where they will begin to experience tangible losses in function secondary to joint damage. Common examples include soft-tissue contractures and tendon ruptures of the hand (the extensor tendon being a common site of rupture). The appearance of rheumatoid nodules on examination and x-ray evidence of erosions are hallmarks of stage 3. Also, systemic manifestations begin to develop in this stage, the most common of which include anemia of chronic disease, pericarditis, weight loss, and various vasculitides.

Stage 4 is considered the “end stage” of RA. By this time, joints have undergone so much degeneration, there is little synovium left to serve as a site for inflammation (i.e., the so called burned out phase). Of note, patients with disease activity greater than 15 years may develop amyloidosis. The mortality rates of patients in this late stage rival that of cancer, stage 4 Hodgkin lymphoma, and three-vessel coronary disease (17).

RA affects a broad population ranging from children to the elderly and has a spectrum of presentation from transient episodes of monoarthritis to the more common active systemic disease. In children, it is classified as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), for which there is a separate set of diagnostic criteria and treatment protocols, the specifics of which are beyond the scope of this chapter. The onset and pattern of RA typically follow the natural history as described above (i.e., an insidious onset of a symmetric polyarthritis), but occasionally some patients present with a series of transient, self-limited episodes of monoarthritis or polyarthritis that subsides completely in days to weeks. This presentation is called palindromic rheumatism. Fifty percent of these patients will eventually progress to full RA (1).

DIAGNOSIS

In 1987, the ACR developed a set of criteria that could distinguish patients with established RA from those with other rheumatic diseases. In 2010, the ACR and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) revised those criteria to identify patients at an earlier stage of the disease, highlighting symptoms associated with persistent and/or erosive disease. Research has shown that earlier diagnosis that led to earlier treatment resulted in improved outcomes and minimized irreversible sequelae, because the majority of joint destruction with fixed deformities occurs within 2 years of onset (18).

The 2010 criteria screen patients with confirmed presence of synovitis in at least one joint and the absence of an alternative diagnosis that better explains the synovitis. The criteria focus on scoring four different domains of disease, with a higher score indicating more severe disease: number and site of involved joints (range 0–5), serologic abnormality (range 0–3), elevated acute-phase response (range 0–1), and symptom duration (range 0–1). A total score of 6 or greater, within a 6-month time frame, in properly screened individuals indicates “definite RA” (19,20).

Physical examination findings are described in the Patient Care section, but regarding the 2010 ACR criteria, it is important to note that the presence of small joint involvement (MCP, PIP, 2–5 MTP, thumb IP joints, and wrists) is a more powerful predictor of RA.

LABORATORY TESTS

RF with titer is a serologic marker commonly used to assess for RA, and at a cellular level is defined by autoantibodies (mostly IgM) with a specificity for the Fc portion of the IgG molecule. The importance of RF lies in the positivity of the test (i.e., a higher titer portends a worse prognosis). Extraarticular findings are almost exclusively confined to RF-positive patients. Negative RF results are less helpful, highlighting the utility value of anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs) in making an earlier diagnosis. Of patients with confirmed RA, 35% with an initial negative RF titer will test positive for ACPAs. The mean ACPA titers increase markedly 2 to 4 years before symptom onset.

Four laboratory tests are incorporated into the 2010 ACR criteria. RF with titer and ACPAs contribute to the “serological abnormality” section. For either RF or ACPA, a “low positive” (above the upper limit of normal [ULN]) is worth 2 points, whereas a “high positive” (greater than three times the ULN) contributes three points. Either erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) levels above the ULN contribute 1 point to the “elevated acute phase” section of the criteria.

Other laboratory tests that do not directly contribute to the diagnosis are often ordered for the purposes of ruling out other diseases or in preparation for starting pharmacologic therapy. For example, a negative ANA helps exclude systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Arthrocentesis is helpful for ruling out crystal arthropathies and pyogenic infection. A complete blood count and liver function tests are required prior to treatment with methotrexate. A purified protein derivative (PPD) test is required prior to initiation of biologic agents due to the risk of reactivation of tuberculosis (Box 25.7).

RADIOLOGY

During the initial evaluation, plain radiographs of affected joints should be obtained. It is important to note that small joints in the hand may have commensurate changes in the foot and ankle. As previously described, osteopenia is seen in stage 2 and bony erosions in stage 3. Pathologically, erosions on x-ray represent sections of joint margins where the outer cortex has been destroyed by synovial proliferation. Erosions are seen in affected joints in up to 90% of patients not responding to treatment (21). MRI is more sensitive than plain radiography in early detection of erosions (22), but hasn’t yet been incorporated into any official clinical decision-making criteria. A normal chest x-ray is important prior to initiation of methotrexate due to hepatotoxic side effects and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (Box 25.8).

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS AND OSTEOARTHRITIS

Many patients do not understand the difference between RA and osteoarthritis (OA). Of paramount importance is an understanding that RA is a systemic disease with potential multiorgan involvement.

Box 25.7 Pearl: Synovial Fluid Analysis Findings In Rheumatoid Arthritis

Cloudy & yellow

Cloudy & yellow

Won’t pass “newspaper test” (i.e., newsprint print cannot be read through the vial of inflammatory fluid)

Won’t pass “newspaper test” (i.e., newsprint print cannot be read through the vial of inflammatory fluid)

5,000 to 50,000 leukocytes

5,000 to 50,000 leukocytes

>50% PMNs

>50% PMNs

Box 25.8 Pearl: Advanced Imaging

When clinical status is worsening (i.e., increasing joint pain) and x-rays remain normal, consider musculoskeletal sonography or MRI, which can detect erosions up to 2 years earlier than conventional roentography (23).

When clinical status is worsening (i.e., increasing joint pain) and x-rays remain normal, consider musculoskeletal sonography or MRI, which can detect erosions up to 2 years earlier than conventional roentography (23).

Radiological differences between RA and OA are described below.

Overall, joints affected by RA are warm and tender, reflecting an inflamed synovium. Areas of synovial proliferation may be palpably soft, whereas joints in OA are hard and bony due to osteophyte formation. RA predominates in joints with robust synovium, which in the hand include the MCP and PIP joints. In contrast, OA affects the distal interphalangeal joints and carpometacarpal joint of the thumb. Typically, patients with RA will notice the worst joint stiffness in the morning for a prolonged period of time, as compared to the brief stiffness or “gelling” which is typical for the OA patient. As opposed to RA, there are no specific serologic markers for OA (Table 25.1).

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Pharmacologic therapy for RA has changed drastically since the early 20th century, starting with aspirin and gold salts through the 1940s.

The discovery of steroids in the 1950s was initially greeted with great fanfare by the medical community; however, over time further use revealed their limitations and shortcomings. Nonetheless, they remain an important part of medical management of RA. Further advances were seen with the discovery of DMARDs in the 1970s, but significant systemic side effects also frequently interfered with long-term use. The turn of the 21st century brought advancements with the advent of the “biologic” class of medications, which targets specific immunologic cytokines or receptor sites.

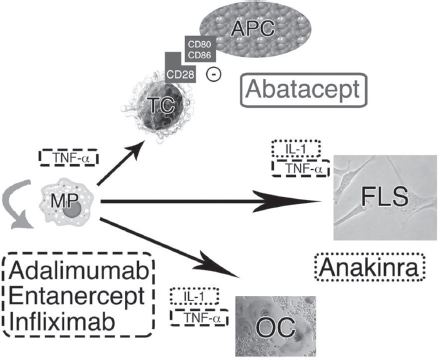

In 2012, the ACR revised their 2008 guidelines for the use of DMARD and biologic agents for RA (24). Examples of currently utilized DMARDs include hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, and methotrexate. Biologic agents include the nontumor necrosis factor (TNF) abatacept, rituximab, and tocilizumab; and the anti-TNF: adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab. New biologic agents are constantly being introduced in the market (Figure 25.1).

Prior to initiation of pharmacologic therapy patients should meet the proper diagnostic criteria (see above). ACR recommendations diverge between patients with early and established RA. In early RA, suggestions for therapy depend on disease activity (scored as low, moderate, or high) and on presence or absence of “features of a poor prognosis.” For early RA, low disease activity, and no poor prognostic factors, the recommendation is to start with DMARD monotherapy (which is most often methotrexate). In early RA, as disease activity and prognostic factors worsen, the ACR recommends adding an additional DMARD. Anti-TNF agents for early RA are reserved for patients with both high disease activity and poor prognostic factors.

TABLE 25.1 Radiological Differences (24)

| RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS | OSTEOARTHRITIS |

Sclerosis | ± | ++++ |

Osteophytes | ± | ++++ |

Osteopenia | +++ | 0 |

Symmetry | +++ | + |

Erosions | +++ | 0 |

Cysts | ++ | ++ |

Joint space narrowing | +++ (symmetric) | +++ (asymmetric) |

Source: From West et al (23).

FIGURE 25.1 Cytokine networks are displayed, along with accompanying sites of action of several popular biologic agents. Macrophages (MP[i]), fibroblast-like synovioctyes (FLS[ii]), and T cells (TC[iii]) are depicted with selected cytokines and their targets. Several cytokines activate osteoclasts (OC[iv]), the primary cell identified in the bony erosions seen in rheumatoid arthritis. IL-1 and TNF-alpha are integral parts of the cascade of cellular autoimmunity. Adalimumab (Humira®), entanercept (Enbrel ®), and infliximab (Remicade®) are examples of TNF-alpha blockers [dashed outline]. Anakinra (Kineret®) is an antagonist of the interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor [dotted outline]. Abatacept (Orencia) is a selective costimulation modulator [solid outline], as it inhibits T-cell activation by binding to CD80 and CD86 on antigen presenting cells (APC), thus blocking the required CD28 interaction shared between APCs and T cells.

For patients with established RA, making modifications to pharmacologic therapy becomes a complex process that not only depends on disease activity and prognostic factors, but also takes into consideration failed therapies and adverse reactions.

EULAR has a similar, but separate set of recommendations regarding medical therapy (29).

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids are being used as a bridging medication (i.e., in the interim between the initiation of DMARD therapy and the time that it has a clinical effect, often measured in months from treatment initiation), for combination strategies along with DMARDs (due to delayed onset of action), for flares, and for treatment of vasculitis.

Several studies evaluated groups of patients, all of whom were starting a DMARD, and compared those who were also started with a glucocorticoid (usually prednisone) versus those whose initial therapy only added a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) or placebo. Better clinical outcomes, including pain and joint tenderness, were reported in the glucocorticoid groups (30). When glucocorticoids are added to an already existing DMARD monotherapy regimen, studies have shown improvements in signs, symptoms, and function, especially radiographic progression (31). Difficulties still remain regarding the optimal duration and dosage of glucocorticoid treatment, and in addition, when to consider discontinuation.

REMISSION

While the goal of rehabilitation is preservation of function, the goal of medical therapy ultimately is remission. The original ACR criteria for clinical remission, published in 1981 (32), depended on the presence of five of the following six factors for 2 months (assuming a lack of systemic symptoms, i.e., vasculitis, pericarditis, myositis, pleuritis, weight loss, fever): no fatigue, morning stiffness for 15 minutes or less, no joint pain, no joint tenderness to palpation or ROM testing, no soft tissue or tendon sheath swelling, ESR less than 30 (women) or 20 (men). ACR/EULAR redefined remission in 2011 (33) as the fulfillment of all of the following: tender joint count less than or equal to 1, swollen joint count less than or equal to 1, CRP less than or equal to 1 mg/dL, patient global assessment less than or equal to 1 (on a 0–10 scale). These criteria have been effective in identifying patients who have long-term courses that were better than those who did not meet the definition of remission. The 2011 guidelines set the new standard for remission for future clinical research trials.

FLARES

A flare is described as “a worsening of disease activity of sufficient intensity and duration to consider a change in therapy,” (34) but there is no current consensus for objectively diagnosing a flare period. Physiologically, flare represents an activation of inflammatory mediators in the synovium. The EULAR recommends that rapid remission is the primary goal of treatment in every patient, and strict monitoring should dictate the adjustment of medication as frequently as every 1 to 3 months (31).

PROGNOSIS

Predictors of a poor prognosis include functional limitation (e.g., Health Assessment Questionnaire [HAQ] score or similar valid tools), extraarticular disease (e.g., presence of rheumatoid nodules, RA vasculitis, Felty syndrome), positive RF or anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, and bony erosions by radiograph (25). Other poor prognostic factors include persistent swelling of the PIP joints, flexor tenosynovitis of the hands, a large number of swollen joints, and impaired functional status at time of diagnosis. A good prognosis has already been outlined in the section on remission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree