Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Nikhil N. Verma MD

Russell F. Warren MD

Thomas L. Wickiewicz MD

History of the Technique

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction continues to be one of the most common procedures performed in orthopedics.1 Although primary reconstructions result in a satisfactory outcome more than 75% to 90% of the time, a significant number of patients may still require revision procedures.2,3 The approach to revision surgery should follow the same principles as those applied to primary reconstruction. The etiology of failure should be initially identified, allowing the surgeon to plan a revision procedure to address deficiencies that lead to failure of the primary reconstruction. Results of revision surgery to date have been inferior to primary reconstruction. However, as experience with revision cases expands, and with continued improvement in arthroscopic techniques, we believe that good results can be achieved.

Indications and Contraindications

The indications for revision ACL reconstruction are based primarily on the etiology of failure, which can often be elicited from the patient history and the patient’s symptoms. It is important to listen to the primary complaints of the patient, as this will help differentiate between recurrent instability, pain, or stiffness. The timing of failure can also provide an important clue in determining the etiology of failure. Early failure (within 6 months) is often due to a technical error such as failure of fixation, incorrect tunnel placement, or improper tensioning. Late failures (after 1 year) can be caused by failure of graft incorporation, traumatic rerupture, or progression of traumatic arthrosis.4,5,6 The main indication for revision ACL reconstruction is recurrent instability that impairs quality of life.

A thorough physical examination should be performed on all patients who have failed a primary reconstruction. The patient should be examined standing and during gait to assess alignment and evaluate for varus or valgus thrust. Range of motion should be accurately evaluated, particularly to ensure full extension is present. Instability examination, including Lachman and pivot shift testing, should be performed. Finally, a thorough evaluation of the integrity of the medial structures and posterolateral corner should be performed as failure to address injuries to these structures has been reported as a cause of early failure after ACL reconstruction.7,8 Correction of instability at the side of the knee is important in revision surgery as excess stresses are placed on the ACL graft with varus or valgus instability and particularly with increases of external rotation of more than 10 degrees to 15 degrees.

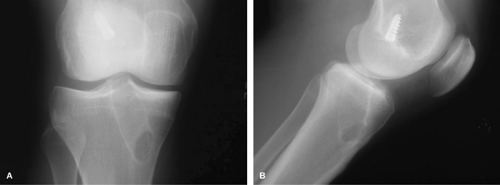

Plain radiographs should be obtained in all cases of failed ACL reconstruction. Specific views required include standing anteroposterior and lateral views, a merchant view, a notch view, and a weight-bearing anteroposterior 45-degree flexion view.9 The tibial and femoral tunnels can be evaluated on both the AP and lateral views to evaluate for tunnel widening and position, as well as the presence of retained hardware (Fig. 41-1A,B). The flexion weight-bearing view can be used to assess for early degenerative disease, which can affect prognosis.9 Finally, if any malalignment is appreciated on physical examination, a full-length standing mechanical axis view should be obtained to determine if an alignment-correcting osteotomy is necessary in addition to or in place of ligament reconstruction.

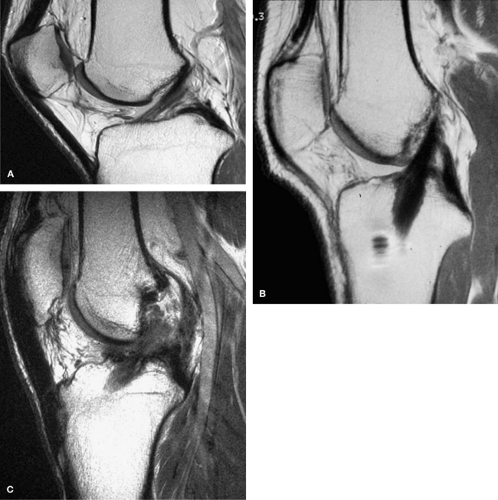

In most cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should also be obtained as a routine preoperative study. MRI allows for direct evaluation of the integrity of the ligament graft10 (Fig. 41-2A,B,C). Tunnel position as well as tunnel

widening can also be evaluated in both the sagittal and coronal planes. However, it should be noted that although the MRI may demonstrate graft integrity with a uniform low signal, the graft may be nonfunctional with persistent knee instability and a positive pivot shift test. The integrity of the menisci can be evaluated to allow for planning of alternate procedures that may be required at the time of revision surgery. The competency of the medial and lateral structures can be evaluated and correlated with the physical exam findings. Finally, with the development of newer cartilage sensitive MRI techniques, the integrity of the articular cartilage can be evaluated to help identify degenerative changes that can affect prognosis.11

widening can also be evaluated in both the sagittal and coronal planes. However, it should be noted that although the MRI may demonstrate graft integrity with a uniform low signal, the graft may be nonfunctional with persistent knee instability and a positive pivot shift test. The integrity of the menisci can be evaluated to allow for planning of alternate procedures that may be required at the time of revision surgery. The competency of the medial and lateral structures can be evaluated and correlated with the physical exam findings. Finally, with the development of newer cartilage sensitive MRI techniques, the integrity of the articular cartilage can be evaluated to help identify degenerative changes that can affect prognosis.11

Fig. 41-1. (A) Anteroposterior and (B) lateral radiograph demonstrating significant tibial tunnel widening after primary ACL reconstruction. |

Fig. 41-2. MRI demonstrating (A) normal anterior cruciate ligament and (B) reconstructed ligament with bone-patellar tendon-bone autograft, and (C) traumatic graft rerupture. |

Absolute or relative contraindications to revision reconstruction are relatively limited. Absolute contraindications include active local or systemic infection. Relative contraindications include significant degenerative changes. In these cases, care must be taken to assess whether the major complaint is pain or instability. If instability is present, revision reconstruction may still be indicated with the limited goal of restoring stability with activities of daily living. In cases in which pain and degenerative changes are accompanied by malalignment, consideration should be given to isolated osteotomy or combined osteotomy and revision ACL reconstruction. Previously we felt that patients with both degenerative disease and a positive pivot shift examination required both procedures. Subsequently, we have noted that the pivot shift examination will decrease or be eliminated by a closing wedge osteotomy that decreases the slope of the tibial plateau, thus eliminating the need for revision ACL reconstruction in some patients.

Surgical Technique

Preoperative Planning

In order to understand the surgical techniques and principles associated with revision ACL reconstruction, one must first understand the potential etiologies of primary reconstruction failure. Proper identification of the etiology of failure is necessary to properly plan the approach to revision surgery. Although potential causes of failure also include loss of motion, persistent pain, and patient dissatisfaction, in this chapter we will focus on recurrent instability.

In our experience, return of instability after ACL reconstruction can be classified into three broad categories. Classification of patients into one of these three categories is based primarily on the patient history and physical examination. The first category is traumatic graft rerupture. This group of patients presents with a complaint of recurrent instability after a single event trauma in a previously stable knee. The mechanism of failure is the same as that which occurs in a native ACL rupture, and the primary reconstruction can be assumed to have been optimally placed. Important considerations in these cases include identification of the graft used for the primary reconstruction, and appropriate graft selection for the revision procedure. The surgeon may choose to avoid grafts that have been associated with slightly higher failure rates such as four-strand hamstring tendon (publication pending, Wickiewicz TL, Williams RJ)12 in favor of autograft patellar tendon or allograft tissue. Given that the primary reconstruction resulted in a stable knee, it is assumed that the primary procedure was technically well done and the same tunnels as those used for the primary surgery can be used for the revision.

The second category of recurrent instability is atraumatic graft failure. These patients present with a technically well-done reconstruction, but with progressive return of instability in the absence of trauma. Potential sources of failure in these cases include failure of graft biological integration, improper graft tension, failure of bone healing, or missed associated instabilities such as persistent medial laxity or posterolateral corner deficiency.7,8,17 In these cases, the surgeon must again be cognizant of the graft used for primary reconstruction when choosing an appropriate graft for the revision procedure. Furthermore, a careful physical examination should be performed to assess for alternate instability patterns that can predispose an ACL reconstruction to early failure. These secondary instability patterns must also be corrected at the time of revision surgery in order to achieve a successful outcome.

If no coexisting pathology is identified, tunnels are assessed based on preoperative radiographs and MRI. In most cases, the tunnel position is optimal and the same tunnels may be used for the revision procedure. If tunnel widening is present, a decision should be made as to whether this can be addressed at the time of revision using techniques such as larger bone plugs, stacked interference screws, or single stage bone grafting, or if a two-stage procedure is required (Fig. 41-3A,B,C). Careful attention should be paid to thorough graft removal, proper graft tensioning, and secure graft fixation.

The third category of recurrent instability is graft failure. This can occur due to a malpositioned graft or a failure of fixation. Loss of fixation can occur secondary to poor bone quality, screw breakage, screw divergence, or graft damage during screw insertion.18,19 If recognized early (within the first week) it may be amenable to revision fixation. However, in most cases, revision reconstruction is necessary. If bone quality is poor, options include compaction drilling or bone grafting. Supplementary fixation such as EndoButton (Acufex, Mansfield, OH) fixation on the femoral side or soft tissue button fixation on the tibial side can also be used. Whenever possible, aperture fixation should be achieved. If graft injury has occurred during femoral screw placement, the graft can be reversed placing the tibial bone block on the femoral side and using soft tissue fixation techniques on the tibial side.

Graft malposition can occur on either the femoral or tibial tunnel. The most frequent cause of a need for revision surgery is incorrect tunnel placement on the femur. Tibial tunnel placement is important to avoid a vertical graft, but

malposition is much less frequent. Anterior femoral tunnel placement results in flexion deficits and early graft failure due to impingement in extension20 (Fig. 41-4A). In this case, a proper posterior tunnel may be placed posterior to the original anterior tunnel (Fig. 41-4B). If pre-existing hardware is not impeding proper tunnel placement, it should be left in place to avoid creating a larger defect. If sufficient room is not available to place a correct posterior tunnel, a two-stage procedure may be necessary with initial bone grafting followed by revision reconstruction in 12 weeks. Posterior femoral tunnel position with femoral cortical compromise can be revised using a two-incision technique to create divergent tunnels. If this is not possible, a two-stage revision should be considered. Central femoral tunnel position results in a vertical graft, which provides anteroposterior stability without rotation control (Fig. 41-5A). This can be manifested on physical examination with a negative Lachman exam and a persistent pivot shift. If adequate bone stock remains, a proper femoral tunnel should be created using either an endoscopic or two-incision technique. (Fig. 41-4B) Otherwise, a two-stage revision should be considered.

malposition is much less frequent. Anterior femoral tunnel placement results in flexion deficits and early graft failure due to impingement in extension20 (Fig. 41-4A). In this case, a proper posterior tunnel may be placed posterior to the original anterior tunnel (Fig. 41-4B). If pre-existing hardware is not impeding proper tunnel placement, it should be left in place to avoid creating a larger defect. If sufficient room is not available to place a correct posterior tunnel, a two-stage procedure may be necessary with initial bone grafting followed by revision reconstruction in 12 weeks. Posterior femoral tunnel position with femoral cortical compromise can be revised using a two-incision technique to create divergent tunnels. If this is not possible, a two-stage revision should be considered. Central femoral tunnel position results in a vertical graft, which provides anteroposterior stability without rotation control (Fig. 41-5A). This can be manifested on physical examination with a negative Lachman exam and a persistent pivot shift. If adequate bone stock remains, a proper femoral tunnel should be created using either an endoscopic or two-incision technique. (Fig. 41-4B) Otherwise, a two-stage revision should be considered.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree