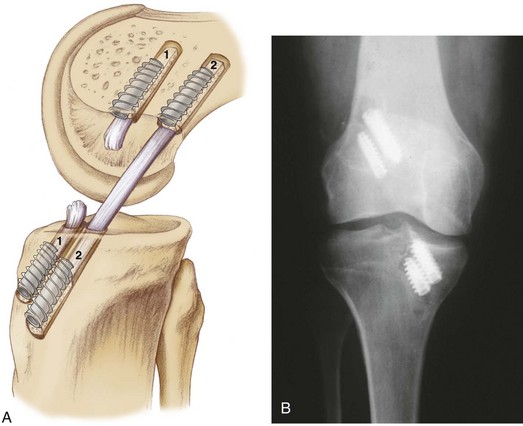

Chapter 76 Reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the most common surgical procedures performed by orthopedic surgeons. However, despite its overwhelming success, 3% to 25% of patients may experience a failure of their reconstruction. Large multicenter studies have suggested that allografts result in higher failure rates in younger athletic patients,1 but failure can occur with any graft type or patient demographic if the appropriate principles are not followed in the primary reconstruction. In the majority of failures, technical errors can be identified and must be corrected at the revision procedure for knee stability to be restored. This chapter discusses the surgical planning and techniques for revision ACL reconstruction. Classification of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Failures The most common cause of failure in primary ACL reconstruction is technical error in tunnel placement, typically involving vertical placement of the femoral tunnel (Fig. 76-1). Historically, concern for ACL-roof impingement in extension led some surgeons to place their tibial tunnels too posteriorly. If the femoral tunnel is then drilled transtibially through the posterior tibial tunnel, a subsequent high (anteromedial [AM]) graft position will result from the orientation of the drill guide. The ACL graft is then malpositioned between a posterior tibial tunnel and a high or vertical femoral position. It should also be noted that even with an independent femoral tunnel in an “anatomic” position on the femoral wall, a posterior tibial tunnel will create a vertical graft in the sagittal plane and may not adequately address rotational stability. This mismatched graft position may diminish impingement and improve anteroposterior (AP) stability; however, it fails to restore normal rotational stability of the knee. Abnormal biomechanics are observed, and patients may report subjective instability even though they have a normal Lachman test result and minimal KT1000 side-to-side difference.5,21 Their rotational instability, however, manifests with a positive pivot glide or 1+ pivot shift even though the Lachman and anterior drawer test results may remain normal. It is important to keep in mind that range of motion may provide important clues regarding the presence of notch impingement and, most important, accurate tunnel placement.2 Regardless, to restore more normal knee kinematics, patients may require a revision ACL reconstruction. Several graft options are available for revision ACL reconstruction. Autografts include hamstring tendon, quadriceps tendon, and patellar tendon from the ipsilateral or contralateral knee. Allograft options include Achilles, patellar, hamstring, quadriceps, and tibialis anterior tendons. Our preference is to use allograft tissue if a patellar tendon autograft has been harvested previously. Although some surgeons prefer the use of a contralateral patellar tendon graft, we have noted that most patients do not want to have their “normal” knee surgically violated. Although biomechanical characteristics of quadrupled hamstring grafts are more than adequate for revision reconstruction, secure fixation in the expanded tunnels can be difficult, especially when soft tissue grafts had been used primarily. Patellar tendon allograft provides bone for supplemental grafting, and extra-large bone blocks can be customized to provide improved tunnel fill for primary interference fixation. In our institution we have historically used nonirradiated patellar tendon allograft for revision procedures, with excellent results.3 Box 76-1 outlines the specific steps of this procedure. It is critical to consider whether former hardware will require removal or whether it may be bypassed at revision surgery. Various interference screws are commercially available with differing morphologic appearances radiographically. Most can be removed with a standard 3.5-mm screwdriver, but every effort should be made to determine the specific brand of the screw to prepare necessary specialized equipment. This is the first decision point; if previous tunnels are nonanatomic and nonoverlapping, the hardware can generally be left in place (Figs. 76-2 and 76-3). If the tunnels will overlap, the hardware may require initial removal for the new tunnel to be made, but it may have to be subsequently reinserted to provide construct fixation stability. In our experience, bioabsorbable screws are generally not resorbed at the time of revision surgery and frequently fracture on attempted removal secondary to softening. The surgeon may therefore have to ream through these screws to properly position the new tunnel.

Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Preoperative Considerations

Graft Choice

Surgical Technique

Specific Steps

3 Removal of Old Hardware

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Revision Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction