Chapter 64 Repair and Reconstruction of the Medial Patellofemoral Ligament for Treatment of Lateral Patellar Dislocations

Surgical Techniques and Clinical Results

Surgical Indications

The medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) is the primary soft tissue restraint to lateral patellar displacement in early flexion6; it is in early knee flexion that almost all noncontact lateral patellar dislocations occur. The biomechanical role of the MPFL is to contain the patella when it is subjected to the extremes of motion secondary to a lateralizing force. The goal of an MPFL repair or reconstruction is to restore the loss of the medial patellar soft tissue stabilizer that has been torn and may be chronically lax because of recurrent lateral patellar dislocations.

Anatomy of the Medial Side of the Knee: Surgical Implications

Knowledge of the medial side knee anatomy is necessary for proper surgical execution of MPFL reconstruction techniques. The capsuloligamentous structures on the medial aspect of the knee have been described as being in three layers.46 Layer 2 is the ligament layer in which the MPFL and superficial medial collateral ligament (MCL) are situated.

The MPFL runs transversely from the proximal half of the medial patellar border to the femur, near the medial epicondyle. Although some fibers of the MPFL fan out and have a broad attachment, the most consistent attachment site is the saddle between the epicondyle and the adductor tubercle. The patellar attachment of the MPFL is wider than the femoral attachment and approximates the upper third of the medial border of the patella, typically at the location where the perimeter of the patella becomes more vertical. As a percentage of the longitudinal length of the patella, Nomura and colleagues30 have reported that the MPFL insertion is 27% ± 10% from the proximal extent of the patella. The MPFL acts as a check rein restraint to lateral deviation of the patella. As the knee progresses into flexion, patellofemoral congruence, and trochlear geometry, in particular the slope angle of the lateral trochlear facet, provide the major restraints to lateral patellar displacement.14

The medial patellotibial ligament (MPTL) is in a more superficial plane than the MPFL and is an oblique condensation of the medial patellar retinaculum. It attaches to the tibia approximately 1.5 cm below the joint line, close to the insertion of the medial collateral ligament, although individual components of the medial retinaculum are more difficult to assess as dissection extends distally.46 The MPTL is uniquely positioned to help resist superior and superolateral translation of the patella because of the oblique orientation of its fibers. However, the role of the MPTL in resisting lateral patellar displacement is debated, ranging from being an important secondary stabilizer21 to being functionally unimportant.6

Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Repair

Primary Repair of the Medial Patellofemoral Ligament

Imbrication of the medial retinaculum has long been a component of surgical procedures for lateral patellar dislocations. However, with the increasing focus on MPFL reconstruction, there has also been greater scrutiny of the results of primary and secondary repair of the ligament itself. Unfortunately there are many variations in the techniques of MPFL repair, making it difficult to compare one surgeon’s experience with another’s. Moreover, it has recently been demonstrated that the location of MPFL injury may further stratify patients into risk categories for recurrent dislocation. In a 7-year follow-up study37 of patients with a primary traumatic patellar dislocation treated nonoperatively, those with a femoral avulsion of the MPFL were at significantly greater risk of developing patellar instability than those with midsubstance tears or disruption at the patellar insertion.

Some authors have recommended against medial repair for first time patellar dislocations. In a randomized controlled study of non-operative management versus repair undertaken at a mean of 50 days after presentation to an emergency department, Christiansen and associates4 have reported a 17.5% redislocation rate in the operative group compared with 20% in the nonoperative group. In another level 1 study, Nikku and coworkers27 have reported the 7-year results of a variety of medial repair procedures compared with nonoperative treatment. The outcomes were similar between the two groups both in regard to patients’ self-assessed outcomes and patellar redislocation.

On the other hand, there also are studies that support medial repair. A recent level 1 study36 compared nonoperative treatment versus open medial surgery in younger, mostly male patients. Preoperative MRI in the operatively treated group helped define the location of the MPFL lesion. Fourteen of 18 operatively treated subjects had a medial reefing at the imaged site of injury and 4 had a Roux-Goldthwait procedure. The surgical decision was based on surgeon preference. At 7-year follow-up there were no redislocations in the operative group compared with further dislocations in 6 of 21 patients in the nonoperative group. However, there were no subjective differences between the two groups. A level 2 study3 also reported improved outcomes for acute patellar dislocations treated surgically. Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was again used to determine the location of MPFL injury. Lesions close to the patella were repaired arthroscopically with an outside to inside technique, whereas femoral avulsion injuries were repaired with suture anchors in the epicondyle. At an average of 40 months follow-up, there were no redislocations in the 17 patients in the operative group compared with 8 redislocations in the 16 patients in the nonoperative group.

A variety of arthroscopic techniques of medial soft tissue repair have been developed over recent years.10,18–20 There are numerous studies both supporting and discouraging arthroscopic repair techniques for patellar instability,2,10,19,20,35 but the results are confounded by various combinations of open and arthroscopic techniques. In one such prospective but nonrandomized study, the results of initial arthroscopic medial repair of the MPFL were compared with those of nonoperative management. At a median 7-year follow-up, initial arthroscopic repair was not associated with a reduced incidence of redislocation. Further detailed outcome studies are needed to clarify the role of arthroscopic repair and to endorse any particular arthroscopic procedure over another.

Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Repair Technique

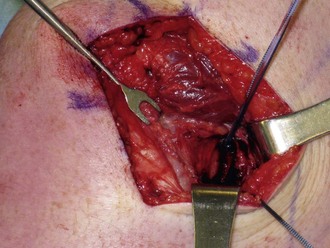

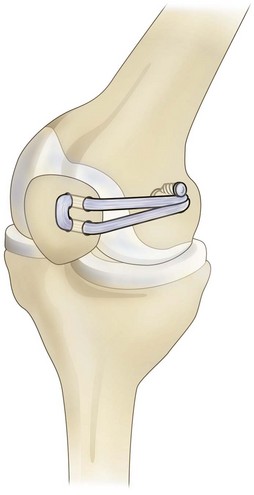

Most commonly, the medial patellofemoral ligament is torn from its femoral origin. For primary repair to the adductor tubercle region, a longitudinal incision is made in the deep fascia and periosteum just proximal to the medial epicondyle. In the initial dissection, the MPFL may be more readily palpated than seen. By holding tension on the tissue with forceps, the patella is translated laterally and the MPFL is identified as that tissue resisting translation (Fig. 64-1). Two suture anchors are then placed into the femur at the attachment site of the MPFL, and mattress sutures are used to repair the ligament with the knee in 30 to 40 degrees of flexion (Figs. 64-2 and 64-3).

If the MPFL is torn off the patella, traction on the medial end of the ligament will not restore patellar stability. In these cases, the MPFL is repaired back to the patella with the use of nonabsorbable sutures placed through drill holes or suture anchors in the patella, in a similar fashion to reconstruction techniques18,20 (see later).

In situations involving midsubstance tears of the MPFL or when there is redundant medial tissue with attenuation, an imbrication of the ligament may be performed.45 A longitudinal incision is made in the MPFL at the point of midsubstance disruption. This incision includes the joint capsule but does not penetrate the synovium. Once the edges are appropriately identified and tension on the anterior end of the medial portion of the ligament confirms a solid femoral attachment, nonabsorbable sutures are passed in a pants over vest fashion. Optimal tensioning of the MPFL is confirmed by ensuring that at least 90 degrees of knee flexion is easily possible with the sutures in place and by tying the sutures with the knee at 20 to 30 degrees flexion. Occasionally, an arthroscopic lateral release may be warranted if there is excessive lateral patellar tilt that cannot be restored to neutral. If performed, the lateral release should be completed prior to tensioning of the medial structures. After the sutures have been tied, patellar tracking is again assessed and a firm end point to lateral patellar displacement should be appreciated. The investing fascia is repaired prior to skin closure.

Medial Patellofemoral Ligament Reconstruction

Basic Principles

Documenting an increase in passive lateral patellar translation beyond the confines of the trochlear groove is a necessary first step because it implies laxity of the MPFL. This is most often established by physical examination with the knee at 20 to 30 degrees flexion, but stress radiographs can also be used.42 If the diagnosis is in question, an examination under anesthesia can be used to document laxity without guarding or apprehension confounding the findings. Arthroscopy is used to identify and address articular cartilage lesions. However, because distention of the joint during arthroscopy usually results in lateral tilt and translation of the patella, one should not attempt to assess lateral patellar tilt and translation based on arthroscopic appearances alone.

When selecting a graft type, consideration should be given to the biomechanical properties of the native MPFL. The ideal tissue for the graft would have similar stiffness, but greater strength, than the native MPFL. All current grafts have both strength and stiffness that are significantly greater than those of the native MPFL. Given this, it seems preferable to use a graft with stiffness that is closest to the native ligament. For this reason, the gracilis tendon may be preferable to the stiffer semitendinosus tendon.16

The graft can be fixed to the patella by suturing it to the periosteum with bone anchors or by using one or two bone tunnels. If there are two strands of tendon, the fixation sites are at the superomedial corner of the patella and at or just distal to the junction of the upper and middle thirds of the medial border of the patella. If bone tunnels are used, they should be just large enough to allow passage of the graft. If two tunnels are used, the graft can be passed through one and into the other to create a sling (Fig. 64-4). Some authors believe that to reduce the risk of fracture, it is important not to breach the anterior cortex of the patella, whereas some techniques deliberately have the tunnel exit the bone anteriorly rather than laterally. Whatever the case, the reconstructed ligament should be placed in layer 2. It should lie deep to the distal end of the vastus medialis anteriorly and deep to the deep fascia more medially, superficial to the capsule of the joint.

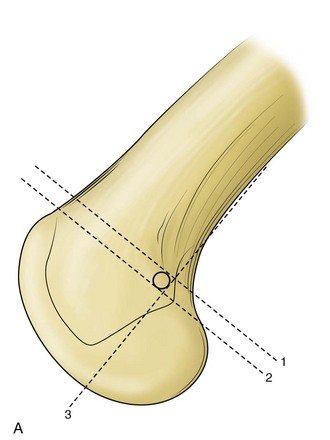

The femoral attachment site can be referenced from the medial femoral epicondyle, 10 mm proximal and 2 mm posterior; or from the adductor tubercle, 4 mm distal and 2 mm anterior. The femoral insertion point can also be identified with fluoroscopic imaging of a true lateral view of the knee33 (Fig. 64-5). However, a critical aspect of MPFL reconstruction is to reproduce the normal tightening of the ligament in extension and relaxation in flexion. The ligament functions as a check rein in early flexion (0 to 30 degrees) and is therefore under the greatest tension in this range of knee flexion. Excessive tension in flexion can lead to painful restriction of knee flexion and articular cartilage overload in the medial half of the patellofemoral compartment. This can mean that the ideal femoral attachment site of the reconstructed ligament needs to be adjusted rather than be based purely on bony landmarks. In techniques in which the femoral attachment is fixed before the patellar attachment, it may be necessary to lengthen the reconstructed ligament to reduce tension in deeper flexion, although this can lead to an undesirable increase in lateral laxity of the patella in early flexion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree