Release of the Sternocleidomastoid Muscle

Gokce Mik

Denis S. Drummond

B. David Horn

DEFINITION

The term torticollis comes from the Latin words tortus (twisted) and collum (neck). It refers to a clinical deformity where the head tilts in one direction and the neck rotates to the opposite side involuntarily.

Congenital muscular torticollis (CMT) associated with a contracture of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle is the most common etiology of torticollis in infants.

CMT is the third most common congenital deformity, next to developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) and congenital clubfoot. The incidence of CMT ranges from 0.4% to 1.3%.4,6,10

Shortening and contracture of the SCM muscle results in tightness that gives the typical clinical appearance, which is detected at birth or shortly thereafter.

Cheng et al4 subdivided the CMT patients into three groups:

Clinically palpable sternomastoid “tumor” or pseudotumor

Muscular torticollis group without palpable or visible tumor but with clinical thickening or tightness of the SCM on the affected side

All the clinical features of torticollis with neither a palpable mass nor tightness of the SCM muscle

ANATOMY

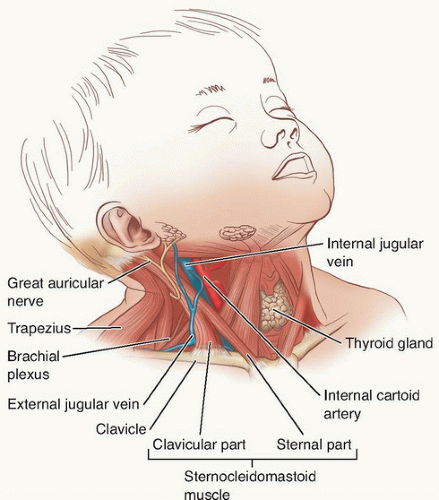

On each side, the SCM muscle passes obliquely across the side of the neck and divides the neck into anterior and posterior triangles.

It originates from two heads:

Sternal head: superior and anterior surface of manubrium sterni

Clavicular head: superior surface of medial third of clavicle. With the two heads combining, the muscle ascends laterally and posteriorly to insert in the mastoid process of the temporal bone.

The clavicular origin of the SCM muscle can vary in size. In some cases, the width of the clavicular attachment may extend to the midpoint of the clavicle.

It inserts on the lateral aspect of the mastoid process.

The functions of SCM are multiple:

With unilateral contraction, it

Flexes the head and cervical spine ipsilaterally

Laterally rotates the head to the contralateral side

With bilateral contraction, it

Protracts the head

Extends the incompletely extended cervical spine

The SCM is innervated by the following:

Spinal accessory nerve (XI)

Ventral ramus of second cervical nerve (C2)

Erb point is located roughly in the middle of the posterior border of the SCM muscle. At this point, the anterior branch of the great auricular nerve crosses the SCM.

The spinal accessory nerve penetrates the deep surface of the SCM muscle, giving off a branch that supplies it. It passes deep to Erb point at the posterior aspect of the SCM.

The external jugular vein is located anterior to the SCM muscle at the proximal part. It crosses the SCM muscle obliquely at its midpoint and ends at the subclavian vein posteroinferior to the SCM muscle.

The SCM protects the carotid artery and internal jugular vein, both of which lie deep to it.

The anatomy of the SCM muscle and important surrounding structures is shown in FIG 1.

PATHOGENESIS

The etiology of CMT in infants is contracture or shortening of the SCM muscle.

Infants with CMT may have a history of difficult or traumatic delivery.

Davids et al7 reported that the position of the head and neck in utero or during labor or delivery can lead to local trauma to the SCM muscle.

Progressive fibrosis and contracture of the SCM muscle may be the sequelae of an intrauterine or perinatal compartment syndrome.7

CMT may occur in association with oligohydramnios, multiple births, firstborn children, and DDH.9

These associated conditions support the theory that CMT is related to restricted fetal motion and malpositioning of the head and neck. These conditions may also be associated with more difficult and traumatic deliveries.

About 50% of patients with CMT are born with a clinically palpable SCM mass (pseudotumor).1,3 This pseudotumor is believed to be a hematoma that undergoes subsequent fibrosis and may result from either birth trauma or intrauterine malposition.

Torticollis may also result from many other diseases such as ophthalmologic problems (eg, Duane syndrome), congenital cervical anomalies, and neurologic problems (eg, posterior fossa tumors).

NATURAL HISTORY

Diagnosis of CMT is usually made at or near birth. Other causes of torticollis generally present later (4 months to 1 year).

A mass (SCM tumor) or fullness in the SCM muscle usually presents within a few weeks or months after delivery.

Typically, the mass decreases in size and disappears between 6 and 12 months of age.

If untreated, contraction and fibrosis of the muscle can occur.

Flexion and rotation deformity of the neck begins in infancy.

Typically, the head turns toward the involved side and the chin points to the opposite shoulder.

Plagiocephaly and facial asymmetry may be present early on; they increase with time.

Flattening of the skull and facial bones can develop on the affected or normal side depending on the sleeping position of the child.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A complete history and physical examination should be done in newborns with torticollis.

The incidence of the breech presentation and birth trauma in children with CMT is higher than the general population.

There is known coexistence of DDH with torticollis.

A clinical examination of the hip and ultrasonography screening are thus warranted for children with CMT.

A previous belief that CMT was associated with metatarsus adductus and clubfoot is not supported by the literature.

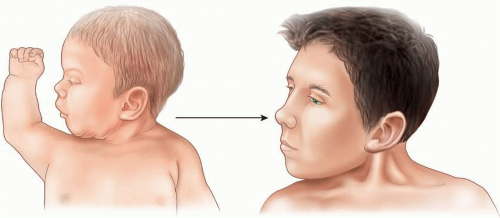

Typically, children with CMT hold their head laterally flexed to the affected side and rotated to the opposite side.

Neck range of motion can initially be normal in infants with CMT. This gradually decreases as the muscle contracture becomes tighter. Later, the typical deformity can usually be observed.

Any restriction of neck motion should be noted during the examination.

The facial bones and cranium are observed for asymmetry. Any flattening of the skull bones should also be noted.

With palpation, a nontender, soft mass 1 to 2 cm in diameter may be found in the lower or middle third of the SCM muscle. With time, this mass changes to a fibrous bundle, and the SCM tendon can then be identified as a tight band that resists correction (FIG 2).

The flexible deformity seen in the early stage can be corrected by gentle stretching.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographs

Standard cervical spine anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views and open mouth odontoid views can be obtained to rule out bony abnormalities such as atlantoaxial rotary subluxation, cervical fusion, cervical scoliosis, and odontoid anomalies.

In older children, radiographic abnormalities such as asymmetry of the articular facets of the axis, tilt of the odontoid process to the side of the torticollis, and sometimes cervicothoracic scoliosis may be observed.2,12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree