CHAPTER 22 Rehabilitation: return-to-play and in-season guidelines

Surgically stabilized shoulders must be protected in the postoperative period, but over-protection has a cost.

Surgically stabilized shoulders must be protected in the postoperative period, but over-protection has a cost. Reestablishing coordinated rotator cuff and scapular muscle activation for proper biomechanics and kinetic chain movements to ensure function is the cornerstone of rehabilitation following surgery to address glenohumeral instability.

Reestablishing coordinated rotator cuff and scapular muscle activation for proper biomechanics and kinetic chain movements to ensure function is the cornerstone of rehabilitation following surgery to address glenohumeral instability.Relevant anatomy and biomechanics

The surgical approach to anterior shoulder stabilization generally is focused on restoration of the anterior glenohumeral ligament complex because this has been shown to be the primary static restraint compromised in anterior instability. Although this anatomy is covered comprehensively elsewhere in this text, pertinent issues are examined here. No definitive studies define the time frame for the healing of a labral lesion or capsule, but several studies and postoperative rehabilitation programs exist that recommend repaired tissues be protected for 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively.1–5 Kim,6 however, in a prospective randomized study demonstrated that an accelerated rehabilitation program of immediate supervised range of motion did not increase injury recurrence rates compared with those immobilized for 3 weeks. The accelerated group also reported less pain and earlier return of motion and functional activity. This study suggests that early mobilization of surgical repairs during the protection phase may be beneficial to a faster and successful outcome.

Perhaps even more important to the athletic patient are the negative effects that arise from immobilization following surgical stabilization. First, it is well established that immobilized ligaments heal with significantly worse biomechanical properties than do mobilized ligaments.7,8 Second, failure to mobilize the shoulder early after surgery results in the formation of dense connective tissue adhesions that lead to decreased range of motion. Additionally, these adhesions may significantly compromise capillary circulation, causing the tissue to become ischemic and the capacity for remobilization to be diminished.9 Third, there is evidence that immobilization itself results in hyperalgesia,10 whereas early mobilization results in earlier pain relief after surgery.11 Finally, immobilization results in significant loss of muscle strength.12 Muscle strength decreases of 22% after 2 weeks13 and up to 54% have been shown after 7 weeks of immobilization, which only partially resolves after remobilization.14

In contrast, several studies provide evidence that controlled mobilization of tendons and ligaments during the protective phase of healing prevents adhesions and reduces stiffness.8,15 Early mobilization also can limit atrophy and restore sensorimotor function (e.g., proprioception, kinesthesia)11 more effectively after surgery. The remainder of this chapter describes a rehabilitation approach that emphasizes early mobilization, within an envelope of safety, for the surgically repaired shoulder.

The initial visit

The most important component to a patient’s successful return to function is clear communication among all parties (i.e., surgeon, therapist, and patient). This should be a goal for the initial postoperative rehabilitation visit. The therapist and surgeon should discuss and be in agreement about the impact of rehabilitation on tissues that were surgically repaired and be clear about indicated, contraindicated, and precaution parameters. Following anterior stabilization surgery, for example, it is critical that one considers the operative approach (e.g., arthroscopic or open) and whether other involved tissues were affected, specifically how the subscapularis was handled. If it was taken down, then its repair must be protected, and this will lead to a very different early postoperative phase. Therapists also should note whether the surgery was a primary repair or a revision, and if the latter, the suspected reasons for the recurrence. Consideration of other surgical factors such as bone loss, labral extension, and quality of repair also must be considered. Failure to understand and account for these surgical aspects or the repair can lead to poor results, such as subscapularis failure.16,17

The early postoperative phase: scapulohumeral rhythm restoration, recruitment, and dynamic stabilization

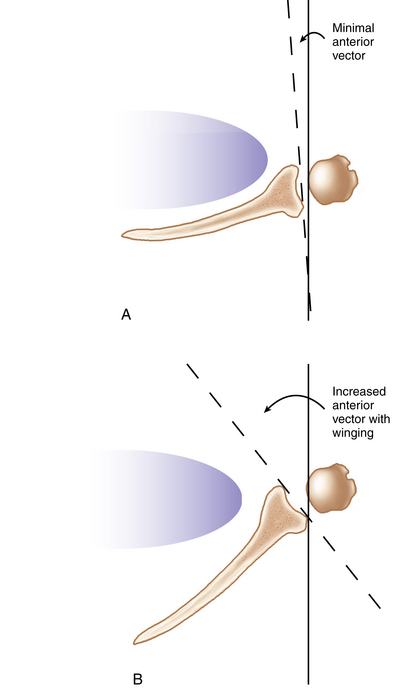

It may seem strange to discuss kinetic rhythm at the beginning of a postoperative rehabilitation protocol instead of at the end, but this is by design. Restoring proper mechanics and coordinated kinetic chain movements is the cornerstone and ultimate goal of our postoperative rehabilitation approach for achieving full, pain-free function; thus, it is the guiding principle for progression. Factors important to proper mechanics and coordinated kinetic chain movements include range of motion, sensorimotor function, glenohumeral and scapular muscle strength, and balanced firing of force couples. It is well understood that shoulder pathology affects scapular kinematics. Specific scapular alterations have been identified in patients with glenohumeral instability,18 including decreased scapular upward rotation and increased scapular internal rotation (e.g., winging) during arm elevation.19 Scapular upward rotation is compromised more between 0 to 90 degrees elevation than above 90 degrees. Mechanically, limited upward scapular rotation places increased forces on tissues that maintain inferior glenohumeral instability. Increased scapular internal rotation reduces anterior bony stability of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 22-1). Therefore, it is clearly important to restore upward rotation postoperatively to prevent instability recurrence. Clinically, incorporating exercises early into rehabilitation for improving is both effective and safe below 90 degrees. Scapular muscles responsible for upward rotation include the upper and lower trapezius and serratus anterior. Emphasis should be placed on improving strength and activation of these muscles while minimizing the overcompensation by the upper trapezius.

In the setting of an arthroscopic stabilization, there is no need to protect musculature in the postoperative period, and immobilization only serves to damage muscular strength and rhythm. Certain modifications must be made for labral repairs that include the biceps tendon, or if the subscapularis has been repaired, but many of the exercises demonstrated in this section are safe even in these settings. In addition to these considerations, pain control is an essential factor in the early postoperative phase. Pain can interfere with muscular firing and can inhibit normal scapular rhythm.20 We use multiple modalities such as compression, cold therapy, and the judicious use of both nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory and narcotic medications to help control pain and minimize its effects on scapular retraining (Fig. 22-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree