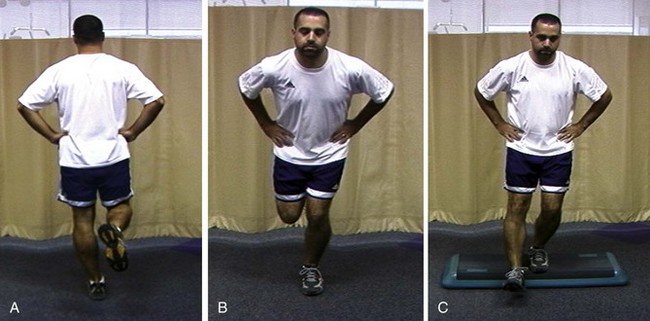

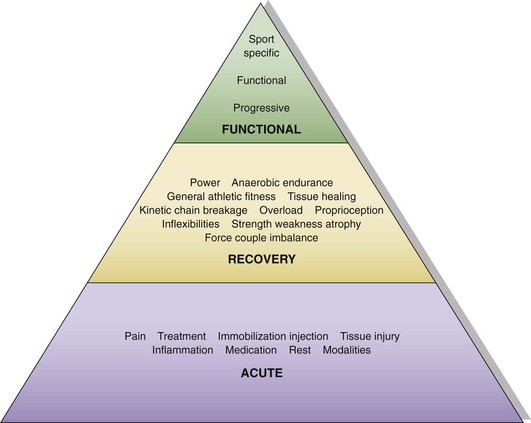

Chapter 2 The orthopedic surgeon plays several roles in shoulder rehabilitation. The first is to understand the basic principles of the kinetic chain. The biomechanical model for striking and throwing sports is an open-ended kinetic chain of segments that work in a proximal-to-distal sequence.1,2 The proximal segment contributions are key components of the sequential activation of body segments that is necessary to accomplish any athletic activity. The kinetic chain harmonizes the interdependent segments to produce a desired result at the distal segment. The goal of the kinetic chain activation sequence is to impart maximum velocity or force through the distal segment (the hand) to the ball, racquet, or other implement. The shoulder does not function in isolation but as a link in the kinetic chain activity that optimizes shoulder function. Alterations in any of the kinetic chain links can affect the shoulder, and alterations in the shoulder can affect the other kinetic chain links. The ultimate velocity of the distal segment is highly dependent on the velocity of the proximal segments. The proximal segments accelerate the entire chain and sequentially transfer force and energy to the next distal segment.2–5 Because of their large relative mass, the proximal segments are responsible for most of the force and kinetic energy that are generated in the kinetic chain.1 As a result, lower extremity force production is more highly correlated with ball velocity than is upper extremity force production.6 The most common local alterations are decreased shoulder internal rotation,7 which creates altered glenohumeral translations,7,8 altered strength or strength balance,7 and alterations in scapular motion and position (scapular dyskinesis).7,9–11 Inappropriate scapular motion can disrupt the normal smooth coupling of scapulohumeral movement in voluntary activation and is present in most patients with shoulder impingement. Distant alterations include lumbar muscle inflexibility and muscle weakness,12 as well as hip and knee inflexibility.13 Because these alterations are common findings in shoulder injury, they need to be assessed through a screening process in the clinical evaluation. This requires a clinical evaluation approach known as “victims and culprits,” in which the site of symptoms is the “victim,” but the “culprits” may include alterations at other sites. The clinical evaluation should include screening tests for hip and trunk posture and functional strength. Our screening examination includes standing posture evaluation of legs and lumbar, thoracic, and cervical spine; bilateral hip range-of-motion assessment; trunk flexibility assessment; and a one-leg stability series (Fig. 2-1), which assesses control of the trunk over the leg. Any observed abnormalities should be further evaluated in more detail. Scapular evaluation is performed from behind the patient. It should assess resting position, and the examiner should note any asymmetries with respect to bony landmarks of the inferior angle, medial, and superior border. Dynamic motion screening involves evaluation of the same asymmetries of scapular control with weighted arm abduction and forward flexion, in both ascent and descent.14,15 Observation of any of the three types (“yes” indicates that asymmetry is seen, “no” indicates that asymmetry is not seen) correlates highly with actual biomechanical alteration and can be reliably used as a marker of scapular dyskinesis that needs to be addressed in rehabilitation.16 The fourth role is to be familiar with the phases of the rehabilitation program, the content and goals of each stage, and the criteria for progression between stages. Rehabilitation may be divided into three phases (acute, recovery, and functional) based on anatomic injury, anatomic healing, functional capabilities, and functional tasks (Fig. 2-2).

Rehabilitation of the Athlete’s Shoulder

The Orthopedic Surgeon’s Roles in Rehabilitation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine