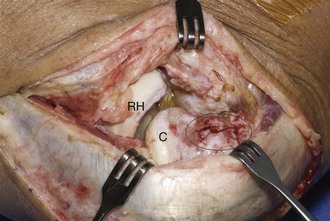

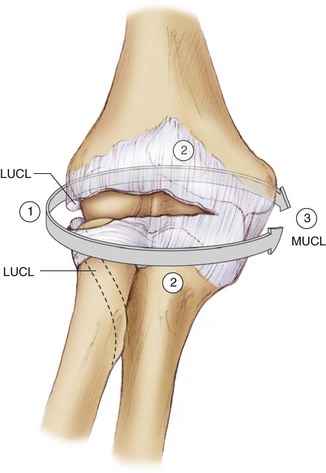

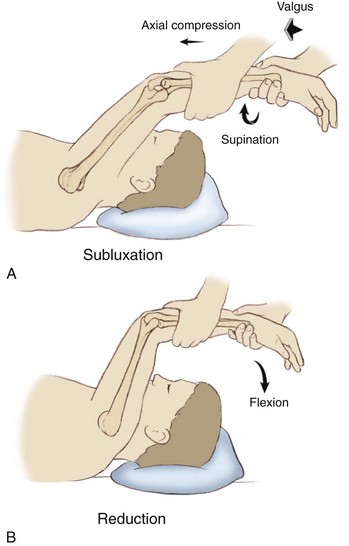

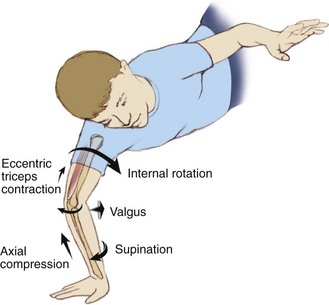

Chapter 47 The term posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI) was coined by O’Driscoll and colleagues1 in 1991, though it was probably first recognized in 1966 (Osbourne-Cotterill). PLRI is now considered to be the most common pattern of recurrent elbow instability. Furthermore, it is currently accepted that chronic lateral collateral ligament (LCL) injury or laxity is the primary pathologic finding in the development of the unstable elbow in the absence of fracture, and it is this injury that is clinically found in PLRI. The lateral or radial side, known as the lateral collateral ligament complex, has four components: the lateral (or radial) ulnar collateral ligament, the radial collateral ligament (RCL), the annular ligament, and the accessory LCL. Deficiency of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (LUCL) is widely believed to be the primary component in PLRI, as demonstrated by O’Driscoll and colleagues.1,2 Studies have shown that LUCL is the essential lesion in PLRI, but clinically the RCL and lateral capsule are also important stabilizing structures.3–5 Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that PLRI is evident only when both the LUCL and RCL are injured, but not when they are cut in isolation.6,7 The LUCL originates proximally on the lateral epicondyle of the humerus and attaches distally to the tubercle of the supinator crest of the ulna. The humeral attachment is historically considered to be the isometric point on the lateral side of the elbow. However, recently it has been elucidated that there is no “true” isometric point because the ligament length changes with flexion and extension.8 The distal attachment is a broad fan-shaped thickening of the capsule that blends with and arches superficial and distal to the annular ligament to insert onto the ulna.3,4 The LCL complex also serves as a posterior sling to prevent posterior subluxation of the radial head. PLRI can be considered a spectrum of instability, consisting of three stages ranging from instability to frank dislocation, according to the degree of soft tissue disruption.1,2 In PLRI the proximal radioulnar joint relationship is maintained, and both the ulna and radius move together as one unit relative to the humerus. This begins with injury to the LCL complex. First, there is subluxation of the elbow in a posterolateral direction such that there is posterior radial head subluxation underneath the humerus. Second, as soft tissue disruption continues to involve the anterior and posterior capsule, there is incomplete dislocation with the coronoid perched underneath the trochlea. Third, there is complete dislocation of the elbow with the coronoid resting behind the humerus. Again, in this spectrum of instability the radioulnar relationship is maintained. In the setting of trauma, the lateral ligamentous injury that results in PLRI usually occurs proximally, at the lateral epicondyle. After an elbow dislocation there is usually a “bare area” visible at the lateral epicondyle where the LCL complex has become avulsed with associated involvement of the RCL and the common extensor tendon origin (Fig. 47-1). Patients have symptoms of pain, locking, snapping, clicking, or recurrent instability, usually preceded by trauma to the elbow or a fall on an outstretched hand (50% to 75%) or, less commonly, a history of previous elbow surgery.5 A history of elbow dislocation is common, although some patients may report recurrent elbow sprains.9 Ligamentous laxity and childhood elbow fracture with a resultant cubitus varus deformity have also been reported to be predisposing factors.10 PLRI can also occur iatrogenically through lateral elbow surgical approaches that disrupt the ligament, arthroscopic elbow procedures, or multiple steroid injections into the region.5,11 In the case of traumatic injury, the mechanism usually involves axial compression, hyperextension, and external rotation (supination) of the elbow (Fig. 47-2). Direct varus stress injuries are a less common cause. These usually occur with a fall onto an outstretched hand. In general, injury to the lateral ligamentous structures is considered the initial stage in a continuum of instability1 (Fig. 47-3). This begins with injury to the LUCL, followed by injury to the entire LCL complex, to the anterior and posterior capsule, and finally to the posterior and anterior bands of the ulnar collateral ligament complex, leading to frank dislocation. Figure 47-2 Axial compression, hyperextension, and external rotation (supination) mechanism of injury. In cases of chronic LUCL insufficiency, physical examination will elicit symptoms of apprehension when the elbow is loaded in the terminally extended and supinated position. The PLRI test (lateral pivot shift test) has been described for the diagnosis of PLRI.1,2 The test is easiest to perform with the patient in a supine position (Fig. 47-4). With the shoulder forward flexed, the forearm is placed in full supination and extension. The elbow is then gently flexed while the examiner applies a slight valgus force and axial load. The radial head is subluxed in the starting (extended) position. Posterior subluxation of the radial head can be palpated as a posterior prominence and dimple in the skin. With further flexion beyond 40 degrees, the radial head spontaneously reduces with a “clunk,” reproducing the patient’s symptoms. With more significant injury and laxity, the clunk of reduction occurs in greater degrees of elbow flexion. This maneuver may be difficult to perform in an awake patient, and thus guarding and apprehension alone are suggestive of a positive test result. Because of guarding, demonstration of the pivot shift may require local (intra-articular) anesthetic or general anesthesia. The test may also be done under live fluoroscopic visualization. Other tests are the posterolateral drawer test, the prone pushup test, and the chair pushup test.12 The posterolateral drawer test is analogous to the drawer or Lachman test of the knee. The patient is placed supine with the arm in the overhead position, such that it represents a leg, and the elbow resembles a knee. The elbow is flexed 90 degrees and supinated. With terminal supination the lateral side of the forearm is rotated away from the humerus, so that the radius and ulna subluxate away from the humerus, leaving a dimple in the skin behind the radial head.

Surgical Treatment of Posterolateral Instability of the Elbow

Preoperative Considerations

Physical Examination

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine