fracture dislocations difficult or impossible. The neurovascular structures are generally spared from serious injury. Soft tissue damage can be extensive with a significant incidence of open fractures. Compartment syndrome of the foot sometimes occurs.

plantarflexion is warranted. If anatomic or near-anatomic reduction of the fracture is achieved, the patient can be splinted in plantarflexion and taken to surgery in a semi-elective fashion since little remaining tension on the blood supply of the talar body will persist. Open reduction and internal fixation should be performed even if an anatomic closed reduction of a Hawkins II fracture has been achieved, as it avoids the inevitable equinus contracture that develops after a prolonged period of casting in plantarflexion (7,8). In Hawkins type III fractures with a dislocated body of the talus, closed reduction is usually unsuccessful and may further traumatize articular cartilage and soft tissue. These cases are surgical emergencies, as the dislocated body of the talus can lead to skin necrosis and disrupts any potential remaining blood supply through the deltoid branches.

TABLE 28.1 Hawkins Classification of Fractures of the Neck of the Talus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

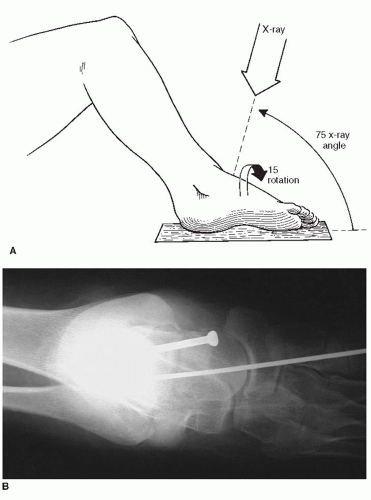

The patient is placed in a supine position, with a bump under the ipsilateral hip to orient the foot perpendicular to the floor. A thigh tourniquet is used and the leg is prepped and draped about the knee. Intraoperative fluoroscopy will be necessary with either a full size C-arm or a mini fluoroscopy unit (Fig. 28.3), depending on the availability and the surgeon preference.

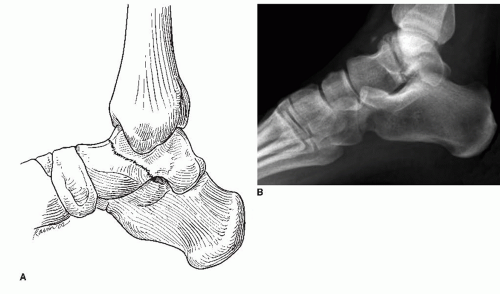

A combined anteromedial and anterolateral approach to the neck of the talus should be used (Figs. 28.4 and 28.5). The anteromedial approach is made from the anterior aspect of the medial malleolus to the dorsal aspect of the navicular tuberosity (Fig. 28.6).

The dissection is carried down to the bone, just dorsal to the posterior tibial tendon. Disruption of the deltoid ligament should be avoided as it will violate some of the blood supply to the body of the talus. The fracture can be visualized and subsequently reduced through this incision. Dissection of soft tissues at the level of talar neck dorsally and plantarward should be avoided such that no further damage to the blood supply occurs.

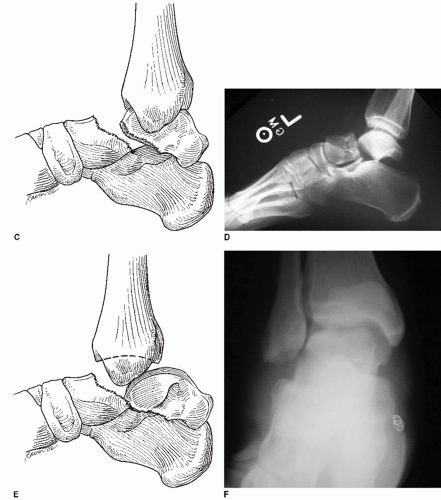

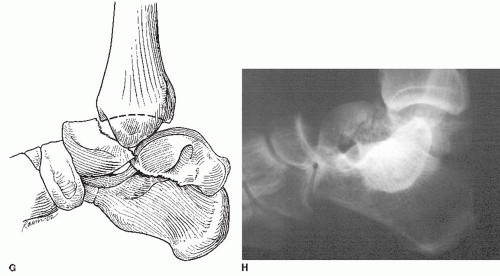

An anterolateral hindfoot incision is made that allows for exposure of the lateral aspect of the talar neck to confirm the accuracy of reduction and to provide another site for hardware placement (Fig. 28.7). Because of limited exposure medially, the fracture may be malreduced with only an anteromedial incision. The second incision also permits removal of any osteochondral fragments from the subtalar joint. Fracture comminution is frequently present on the medial neck of the talus; thus visualizing the lateral aspect of the talar neck can provide a more accurate assessment of the adequacy of reduction since there is less frequently laterally based comminution.

The anterolateral hindfoot incision is made from the anterior aspect of the lateral malleolus toward the base of the fourth metatarsal. The extensor digitorum longus and peroneus tertius tendons are retracted. The extensor digitorum brevis muscle is retracted dorsally.

If osseous fragments are evident in the subtalar joint preoperatively, they should be located and removed, possibly with the aid of a lamina spreader in the sinus tarsi. The subtalar joint can be probed blindly and irrigated to remove any articular debris that may not have been evident on preoperative radiographs.

The fracture is reduced under direct visualization through the medial and lateral incisions. The surgeon must beware of comminution of the medial neck of the talus because it can lead to a varus malreduction of the neck of the talus that subsequently leads to a rigid, supinated foot. The fracture may have a gap on the lateral neck when the medial side has been provisionally fixed in a shortened manner (Fig. 28.8).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree