Radioulnar and Metacarpal Synostosis

I. RADIOULNAR SYNOSTOSIS

CASE PRESENTATION

A 12-year-old male presents for evaluation of an elbow deformity. The patient was in a usual state of health until he sustained a fall onto his elbow while playing baseball. At that time, there was minimal swelling or deformity, though he was noted to have limited forearm rotation. Radiographs of the forearm were obtained to rule out a fracture, and the patient was diagnosed with a “birth defect” (Figure 17-1). He presents now for orthopaedic consultation. Of note, with further questioning, his parents report he’s always had difficulty with certain activities, including fielding a ground ball at second base and swinging a bat.

CLINICAL QUESTIONS

What is the cause of a congenital radioulnar synostosis (RUS)?

Is it hereditary? Are there any associated syndromes?

How is congenital RUS classified?

What are the indications for surgical treatment?

What are the surgical treatment options?

Is there an optimal position for fixed forearm rotation?

What are the complications of surgery for RUS?

What are the expected outcomes?

THE FUNDAMENTALS

Etiology and Epidemiology

Congenital RUS refers to an abnormal connection between the radius and the ulna due to an embryological failure of formation.1 During the fourth to sixth week of gestation, the upper limb bud develops into the fully formed upper extremity. Between roughly the 37th and 57th day of gestation, a distinct humerus, radius, and ulna are formed. During this period, the forearm arises from a single cartilaginous anlage, which separates longitudinally to form a radius and ulna. Failure of separation results in a congenital RUS. As the separation occurs sequentially from distal to proximal, the RUS characteristically involves the proximal third of the forearm. Furthermore, as the forearm is positioned in pronation in utero, the resulting fusion between the radius and ulna results in varying degrees of fixed forearm pronation.2, 3, 4 and 5 It has been hypothesized that both congenital RUS and radial head dislocation are developmentally related, distinguished only by subtle differences in the timing of the developmental insult.6

Given that up to 20% of patients will have a positive family history, it is thought that congenital RUS may be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion with variable penetrance and expressivity.7

Approximately one-third of patients with RUS will have associated syndromes or anomalies, including Apert syndrome, Carpenter syndrome, arthrogryposis, Williams syndrome, and Klinefelter syndrome.3 Other conditions, including polydactyly, syndactyly, carpal coalition, and radial longitudinal dysplasia, have also been associated with RUS. Sex chromosomal anomalies have also been associated with RUS.8

Clinical Evaluation

Given the infrequency with which the condition occurs, diagnosis is often not made until patients are of school age.7 As elbow flexion and wrist flexion-extension are typically unaffected, and young children demonstrate great compensatory rotation through the radiocarpal and midcarpal joints, patients with RUS have little initial functional limitations. The lack of true forearm rotation and usually mild elbow flexion contracture (∽20 degrees) are not usually noted early on in life. Later, relatives, teachers, or coaches will identify limitations of forearm rotation with specific activities (e.g., hand washing at school, toilet training due to inability to place the supinated hand to the perineum, catching a ball, swinging a racquet or baseball bat). It is not uncommon for the diagnosis to be made incidentally on radiographs obtained after traumatic events.

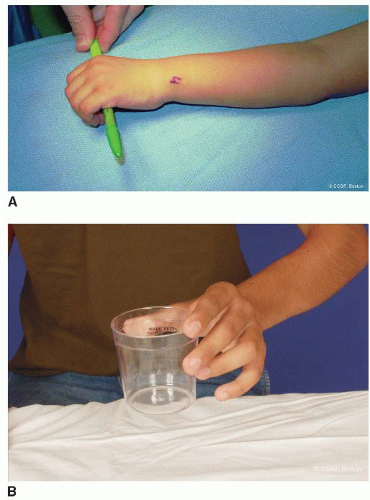

Patients will present with fixed forearm pronation (Figure 17-2). In severe cases, “backhanding” may be seen with hand-to-mouth activities or in placing objects in the

affected palm. Careful physical examination should be performed, as compensatory rotation through the wrist may mask fixed forearm position. Forearm position can be reliably assessed by determining the axis between the radial and ulnar styloids when the arm is adducted and elbow flexed 90 degrees. Elbow flexion and wrist flexion and extension are preserved, and the distal radioulnar joint is typically stable. In severe cases, forearm segment shortening and abnormal elbow carrying angle may be seen. The majority of patients, however, will have minimal impairment of hand function.9

affected palm. Careful physical examination should be performed, as compensatory rotation through the wrist may mask fixed forearm position. Forearm position can be reliably assessed by determining the axis between the radial and ulnar styloids when the arm is adducted and elbow flexed 90 degrees. Elbow flexion and wrist flexion and extension are preserved, and the distal radioulnar joint is typically stable. In severe cases, forearm segment shortening and abnormal elbow carrying angle may be seen. The majority of patients, however, will have minimal impairment of hand function.9

FIGURE 17-2 A: Clinical photographs demonstrating fixed left forearm pronation. B: Compensatory motion is seen through the wrist, simulating forearm supination to neutral. |

Radiographs of the entire forearm will demonstrate a bony connection between the proximal radius and ulna; less commonly, there is a more extensive synostosis. At times, the lack of forearm rotation is due to a cartilaginous or fibrous connection between the two bones. The ulnohumeral is typically normal in appearance. The distal radioulnar joint may be distorted in cases of extreme forearm pronation. Depending upon the severity of involvement, there may or may not be a congenital radial head dislocation or absence of the radial head as it is a part of the synostosis. Often a subtle bow to the proximal ulna is seen. This ulnar bow may be a part of the mild elbow flexion contracture commonly noted on physical examination.

Several classification systems have been proposed. Mital classified RUS into two types.2 Type 1 refers to a synostosis between the radial epiphysis and the metaphysis. Type 2 refers to a synostosis distal to the radial physis, associated with a radial head dislocation. Cleary and Omer based their classification upon the morphology and position of the radial head.7 Type 1 patients have a normalappearing radial head and radiocapitellar alignment with a fibrous synostosis. Type 2 denotes a bony synostosis with a normal-appearing, reducted radial head. Type 3 refers to bony synostosis with a hypoplastic and posteriorly dislocated radial head. In Type 4 RUS, the radial head is dislocated anteriorly.

Surgical Indications

Keep it simple, when you get too complex you forget the obvious. —Al McGuire

Surgery is recommended for functionally limiting loss of forearm rotation; this is dependent upon both the severity of the pronation deformity and whether there is unilateral or bilateral involvement.10 Bilateral involvement with hyperpronation of the forearms results in greater difficulties with daily activities, whereas unilateral involvement with mild pronation position leads to little functional compromise. In their series of 23 patients with RUS observed over 22 years, Cleary and Omer reported that over 95% of patients report little or no limitations with activities of daily living or work.7 Simmons et al.3 and Ogino et al.11,12 both reported that patients with >60 degrees of pronation had difficulties with daily living.

The optimal position of forearm rotation remains controversial. Historically, in cases of bilateral involvement, 30 to 45 degrees of pronation of the dominant limb and 20 to 30 degrees of supination of the nondominant limb were considered ideal.12 Simmons et al.3 advocated that the dominant limb should be positioned in 10 to 20 degrees of pronation with the nondominant limb in neutral rotation. Given the tabletop and keyboarding demands of the modern-day world, mild pronation of both limbs is currently considered ideal.13

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

Not even God can hit a one-iron. —Lee Trevino

While theoretically reconstructing a proximal radioulnar joint would restore forearm rotation and improve function, attempts at synostosis resection and joint reconstruction have been met with near-universal failure. Attempts at simple bony resection have not succeeded.5,14, 15 and 16 Interpositional arthroplasties with soft tissue and metallic implants have been similarly tried.17 More recently, attempts at synostosis resection and free vascularized tissue interposition have been reported, with gains in shortterm forearm rotation.18, 19, 20 and 21 Given the complexity and morbidity associated with these techniques, in addition to the reliability of simpler surgical strategies, microvascular free tissue procedures have not yet become the standard of care for RUS.

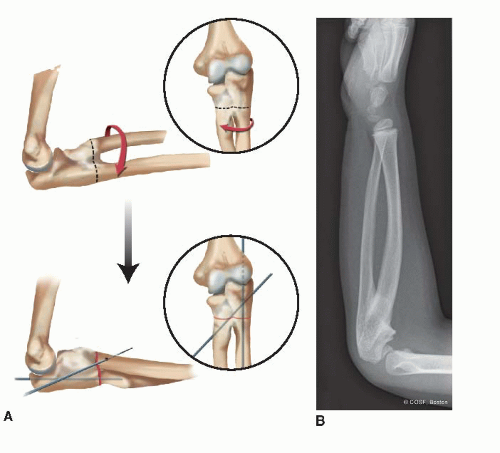

Rather than attempting to create a proximal radioulnar joint where none had ever developed, most current surgical treatment strategies have focused on derotating the forearm-hand unit to a more functional position. A number of techniques have been advocated, all of which involve osteotomies of the radius and/or ulna and derotation from an extreme pronated position to a more functional one. Green and Mital12 advocated osteotomy through the synostosis and K-wire fixation (Figure 17-3). Lin et al.22 described their technique of radioulnar osteoclasis, in which percutaneous osteotomies were performed of the radial and ulnar diaphyses at different levels. After initial osteotomies, no attempt is made at derotation, and a long-arm cast is applied. Approximately 1 week later, the cast is removed and the forearm is derotated under general anesthesia to the desired position. No internal fixation was utilized in their technique, and cast immobilization for an additional 6 to 8 weeks was used until bony healing. A delayed union rate of up to 16% has been reported with this technique.23 Others have advocated variations of this technique using internal fixation with osteotomies of one or both forearm bones.24, 25, 26,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree