Chapter 4 Quality of Life and Economic Aspects

QUALITY OF LIFE

Definition

Quality of life is an ill-defined term that means different things to different people. The concept is vague and multidimensional, and research in this area spans a wide range of disciplines. Of particular concern in the health sciences are those areas that are affected by disease and its treatment, and so to distinguish between QoL in its more general sense and to emphasize its relevance within the context of health, the term health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is frequently used. The concept of HRQOL parallels the World Health Organization’s 1948 definition of health: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity.” Measures of the physiologic processes of disease alone cannot adequately capture the many dimensions of health embodied within this broad definition. Traditionally, health status assessments relied on a “disease” model, in which abnormalities are indicated by objective signs and symptoms. In contrast, the “illness” model relies on subjective feelings of pain and discomfort that may not necessarily result from a pathologic abnormality. Both of these concepts of health—disease and illness—must be taken into account in order to make comprehensive assessments of health status. Health-related quality of life comprises those parts of QoL that directly relate to a person’s health, and may be defined as a measure of a person’s sense of physical, emotional, and social well-being associated with a disease or its treatment. This definition may be broadened to include indirect consequences of disease such as unemployment or financial difficulties.1

Why Measure Quality of Life?

Increasingly, HRQOL is being recognized as an important aspect of chronic diseases such as SLE and is being recognized as a relevant measure of efficacy in clinical trials. OMERACT (Outcomes Measures in Rheumatology Clinical Trials), an international network of experts and opinion leaders, has recommended the inclusion of three outcome measures in SLE clinical trials: (1) a disease activity score, (2) a damage index, and (3) a patient-assessed measure of health status, disability, and HRQOL.2 The importance of QoL assessment in health has been underscored by the need to assess the relative effectiveness and appropriateness of rival medical treatments in a context of increasing pressure on healthcare resources. Increased questioning of the use of various medical treatments and methods of organizing health services has led to a paradigm shift in the approach to measurement of health outcomes.3 Furthermore, measurement of QoL in addition to more objective clinical indicators of disease allows for a more comprehensive assessment of the impact of disease and clinical therapies. Information about broader patient outcomes empowers physicians and patients when making decisions about the most appropriate health care. The challenge remains to identify instruments that will accurately and reliably assess these disease outcomes.

Measuring Quality of Life

Although it has been debated whether QoL assessments should be made by the patient or by a health professional, there is now a general agreement among researchers that patients should complete questionnaires about their QoL themselves. Questionnaires may be administered to patients by trained interviewers in certain situations, such as when the patient is unable to read or write.3 The goal of QoL research is to determine health outcomes from the perspective of the patient, and numerous studies have shown that patients’ opinions may vary considerably from those of both healthcare professionals and patients’ relatives.1 Although one important criticism of patient self-assessment is the occurrence of subjectivity, this subjectivity should, in fact, be viewed as a strength, as it reflects the patient’s point of view.

A plethora of instruments exist that aim to measure aspects of QoL regarded as pertinent to health status, such as life satisfaction, mental health, relationships, fatigue, energy, and vitality.4 Given its multidimensional nature, instruments developed for measuring HRQOL will likely be more accurate if they evaluate a number of dimensions. Most authors agree on the existence of four major domains of QoL: (1) physical status and functional abilities, (2) psychological status and well-being, (3) social interactions, and (4) economic and/or vocational status and factors.5 Tools that measure only one or two of these domains may fail to comprehensively assess an individual’s well-being. Two basic approaches have been used in the measurement of HRQOL: generic instruments and disease-specific instruments.

Generic Instruments

Assessment of HRQOL in patients with SLE has relied largely on the use of generic instruments. Generic instruments are intended for general use, apply to a wide variety of populations, and may be applicable to various illnesses and conditions. They allow for comparisons with other groups, including comparing the relative impact of various healthcare programs.5 It has been argued, however, that generic instruments may be less responsive in specific conditions and as a result will always require supplementation with disease-specific measures in order to detect important clinical changes.3

Earlier health assessment instruments tended to focus on physical symptoms, that is, measuring physical impairment, disability, and handicap. These instruments emphasized the measurement of general health, with the assumption that poorer health indicates poorer QoL.1 However, patients may not respond equally to similar levels of impairment or disability. Newer instruments, such as the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form (SF-36), aim to better assess the subjective nonphysical aspects of QoL and place greater emphasis on emotional and social issues.

Disease-Specific Instruments

Disease-specific questionnaires are designed to measure outcomes for a specific disease. In contrast to generic instruments, disease-specific instruments aim to identify issues pertinent to a specific condition and, as a consequence, may be more responsive in detecting differences in clinical outcomes. Two examples of disease-specific questionnaires include the Stanford Arthritis Centre Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)6 and the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales (AIMS)7; both were developed to assess health status in patients with arthritis and are discussed in detail in a subsequent section of this chapter. As of yet, there are no widely used disease-specific questionnaires for patients with SLE.

MEASUREMENT OF QUALITY OF LIFE IN PATIENTS WITH SLE

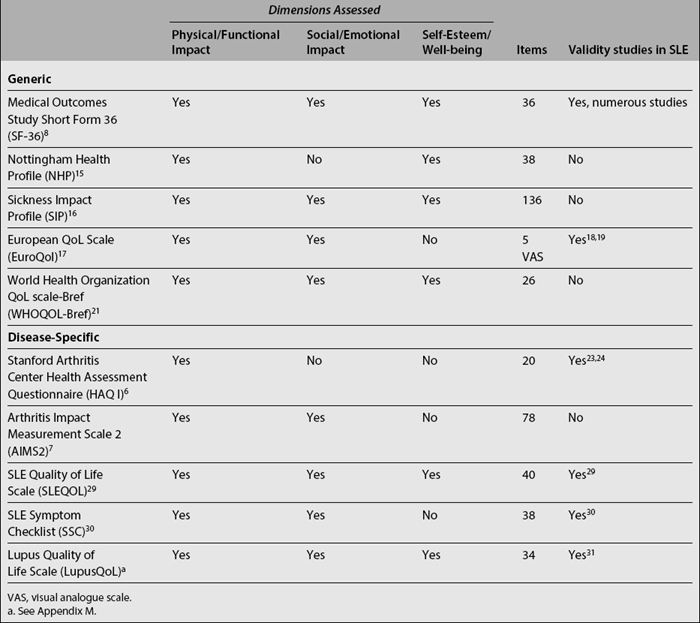

The following instruments have been used to evaluate HRQOL in SLE studies (Table 4.1).

Generic Instruments

The SF-36, developed by Ware and Sherbourne,8 is the most commonly used generic health status questionnaire. It has become the standard health status questionnaire in U.S. health policy research and it is increasingly being used worldwide.9 It is a concise 36-item questionnaire that was designed to be a short, psychometrically sound, generic measure of subjective health status applicable in a wide range of settings.10 It can either be self-assessed or administered by a trained interviewer. Eight domains are measured: physical functioning, social functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, role limitations due to emotional problems, mental health, energy/vitality, pain, and general health perception. These subscales can be summarized into two component scores: the Physical Component Summary score (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary score (MCS), allowing for easier comparisons and reducing the probability of chance findings.11 The SF-36 has been translated into numerous languages and cultures, and has been found to be valid and reliable in various conditions.

The SF-36 has been shown to be a valid and reliable questionnaire in SLE.12 Patients with SLE have been shown to have a poorer QoL than people without chronic illness with respect to all aspects of health.12,13 In a British study of 150 patients with SLE, Stoll and colleagues12 showed that all of the QoL domains assessed by the SF-36, except for emotional role limitations, were significantly lower in patients with SLE than in a British control population of normal adults of working age. In another study, SF-36 results of 120 Canadian SLE patients were compared to normative data from Canadian women of the same age. The authors found that SLE has a negative influence on patients’ QoL, especially with regard to physical health status.14

Nottingham Health Profile

The Nottingham Health Profile (NHP)15 is a 38-item questionnaire that assesses the domains of physical mobility, pain, sleep, social isolation, emotional reactions, and energy level. Its wording is simple and easily understood, and can be completed by patients in 5 minutes. The NHP cannot fully assess the impact of a condition such as SLE on QoL, and for this reason has been often used in combination with other measures, such as a functional disability scale and a measure of psychological disturbance.

Sickness Impact Profile

The Sickness Impact Profile (SIP)16 aims to asses the impact of sickness on daily activities and behavior. It is much longer than the NHP and takes approximately 20 to 30 minutes to complete. It contains 312 items in various dimensions of physical and psychosocial functioning, including sleep and rest, eating, work, home management, recreation and pastimes, ambulation, mobility, body care and movement, social interaction, alertness behavior, emotional behavior, and communication. Both the NHP and SIP have been used in a variety of diseases and have been shown to be reliable and valid. Nevertheless, neither of these questionnaires has been validated in SLE; their use, therefore, cannot be recommended in clinical trials of SLE.

European QoL Scale

The European QoL scale (EQ-5D)17 has been proposed as a potentially useful measure of QoL in SLE studies. It is a simple measure that assesses five dimensions of health status: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. In addition, a visual analog scale provides a self-rated assessment of health status. The EQ-5D was used in a study by Wang and colleagues18 of 54 patients with SLE, evaluating the relationship between self-reported QoL and disease activity, damage, impairment, disability, and handicap. In this study, the EQ-5D was shown to be a valid instrument for the measure of HRQOL. Luo and colleagues have used Singaporean English and Singaporean Chinese versions of the EQ-5D in patients with various rheumatic diseases, including SLE.19,20 Both versions were found to be valid measures of HRQOL in Singaporeans with rheumatic diseases; however, the reliability of these questionnaires requires further investigation.

World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale

The World Health Organization Quality of Life-Bref (WHOQOL-Bref),21 a 26-item abbreviated version of the original 100-item WHOQOL, assesses four dimensions of QoL: physical, psychological, social, and environmental. Preferred because of its crosscultural applicability, Khanna and colleagues recently used the WHOQOL-Bref to assess QoL in SLE patients from India.22 In their study of 73 patients, the physical and psychological domains of QoL were impaired in patients with active disease, whereas the social and environmental domains of QoL were not found to correlate with disease activity.

Disease-Specific Instruments

Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index

The most commonly used measure of functioning in the rheumatic diseases is the Stanford HAQ Disability Index.6 This questionnaire was developed as an “arthritis-specific” instrument and places a significant emphasis on physical functioning. It has been used extensively in the evaluation of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and has also proven useful in the assessment of patients with other conditions. The HAQ is a 20-item scale that assesses activities of daily living (ADL) in eight domains: dressing, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reaching, gripping, and errands and chores.4 Each of these components consists of two or three relevant questions and assistance from others or the use of aids can also be incorporated in the final score. The HAQ is a reliable and valid instrument and has been used widely in clinical trials. In SLE, the validity of the HAQ has been demonstrated by Hochberg and Sutton23 and Milligan and colleagues.24 Hochberg and Sutton demonstrated significant correlations between increased disability and worse global assessment. Milligan and colleagues found that patients with inactive disease had less disability than active patients. A study by Lotstein and colleagues25 showed that women of lower socioeconomic status had more functional disability as measured by the HAQ. One limitation of the HAQ is that it only assesses physical functioning, and so it has been suggested that, for a more complete evaluation, additional questionnaires designed to assess psychosocial functioning should also be used. Two such surveys are the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale and the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ).9

Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale

The AIMS2,7 a revised version of the original AIMS,26 is a 78-item scale that asks respondents to report on physical functioning, ADL, social activities, social support, pain from arthritis, work, level of tension, mood, satisfaction with health status, general health perceptions, overall impact of arthritis, and medication usage.4 Although it assesses a wide range of physical and emotional problems, the AIMS was specifically designed for arthritis outcomes studies and has rarely been used in SLE. The original AIMS has been used in only one SLE study,27 in which 50 women with SLE were compared with age-matched women with rheumatoid arthritis.

SLE-Specific Instruments

Generic measures have the advantage of permitting comparisons across diseases and interventions, an important consideration for policymakers in the allocation of resources. They also allow measurement of dysfunction for individuals experiencing more than one condition. Nonetheless, it has been suggested that such generic measures may not be able to capture elements specific to particular diseases and may not be sufficiently responsive in clinical trials. As noted by Patrick and Deyo,28 disease-specific measures may have greater salience for physicians and better focus on functional areas of particular concern, and may possess greater responsiveness to disease-specific interventions. As such, there has been considerable interest in the development of a disease-specific measure of QoL in SLE. Leong and colleagues29 recently developed and validated a new SLE-specific QoL instrument, the SLEQOL. The SLEQOL is a 40-item questionnaire consisting of six subsections: physical functioning, activities, symptoms, treatment, mood, and self-image. It was developed entirely in English and its performance was studied on 275 SLE patients in Singapore. It was shown to be valid, possessing construct validity, face and content validity, internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and responsiveness. The SLEQOL was found to be more responsive to change than the SF-36. Grootscholten and colleagues30 recently developed a disease-specific questionnaire for lupus patients, called the SLE Symptom Checklist (SSC), that assesses the presence and burden of 38 disease- and treatment-related symptoms. The questionnaire was developed in Dutch and has been translated into English. Reliability and reproducibility were tested in 87 and 28 stable SLE patients, respectively, and it was found to have satisfactory internal consistency and test–retest reliability. The Lupus Quality of Life Scale (LupusQoL),31 a new patient-derived measure of health-related QoL, has also been recently developed. This is a 34-item instrument comprised of eight domains: physical functioning, pain, emotional functioning, fatigue, body image, sex, planning, and burden to others (see Appendix M). This questionnaire has been shown to possess internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and concurrent validity compared with the SF-36. Further evaluation of these instruments is necessary before they can be recommended for routine use. Furthermore, although the question of whether to use disease-specific versus generic measures has been widely debated, there now appears to be a general consensus that generic measures should be used preferentially, supplemented with disease-specific measures where applicable.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH QUALITY OF LIFE IN SLE

Disease Activity

Health-related QoL questionnaires, such as the SF-36, have allowed the study of predictors and associations of impaired QoL in SLE.9 SLE disease activity, as evaluated by various measures, has been assessed in SLE and correlated with QoL. Stoll and colleagues,12 using the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) disease activity instrument, showed that disease activity was closely and significantly correlated with each domain of the SF-36. In fact, the authors of this study noted that even patients with minimal disease activity had significantly impaired QoL. In another study, Sutcliffe and colleagues,13 using the Systemic Lupus Activity measure (SLAM)32 to measure disease activity, showed that a higher SLAM score (i.e., increased disease activity) was an important determinant of health status. Higher disease activity was associated with significantly poorer scores in the SF-36 domains of physical functioning, role limitations (physical), pain, general health, vitality, and social functioning. Fortin and colleagues 33 evaluated the association of two measures of disease activity, the Systemic Lupus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI)34 and the SLAM-R, with health status as expressed on the SF-36. The SLAM-R was correlated with several aspects of the SF-36 while the SLEDAI was not. Gladman and colleagues35 have shown a similar lack of correlation between the SLEDAI and the SF-36. These findings suggest that important differences exist between these disease activity indices, possibly related to the SLAM-R capturing more patient-derived information on lupus activity.

Damage

Damage, whether resulting from the disease process itself or as a result of treatment, is recognized as an important outcome in SLE. Studies that have assessed associations between disease damage and QoL have shown that the major effects in health status result from decreases in physical functioning. Fortin and colleagues,33 in a prospective study of 96 patients, measured disease damage using the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index (SLICC/ACR DI), and correlated it with QoL assessed using the SF-36. Not surprisingly, as stated by the authors, the SLICC/ACR DI correlated with the SF-36 domain physical function at baseline and with its mean value over time. It appears that permanent damage will continue to interfere with physical performance and functioning, whereas other areas of health status such as emotional well-being and social functioning may, with time, adapt to a physical deficit. Other studies have shown no significant correlation between disease damage and health status. In one longitudinal observational study of 87 SLE patients, Gilboe and colleagues36 showed that the best predictors of SF-36 PCS and MCS scores were the respective baseline scores and no significant relationship was found between SLICC/ACR DI score and health status. Gladman and colleagues,35 in an earlier study, also showed no such correlation.

Psychosocial Aspects

Psychological disorders occur frequently in SLE patients. Up to 40% of patients with SLE have diagnosable psychological disorders, most commonly anxiety disorders and depression.37 The importance of psychological functioning in QoL was underscored in a study by Burckhardt and colleagues27 which showed that psychological distress alone was the best predictor of QoL among patients with SLE. Nevertheless, studies on the prevalence of psychological disorders in SLE and physically healthy controls have shown conflicting results, with one study showing higher rates of psychological disorders among patients than among controls,38 and another showing rates that were similar between patients and controls.39

Psychological functioning appears to worsen with increased disease activity and damage, particularly when the disease causes greater pain, helplessness, and physical disability.37,40,41 Given the pervasive nature of SLE and its course, its impact on mental health is not surprising. Moreover, poor baseline psychological functioning may, in turn, contribute to worse physiologic outcomes in SLE, as has been seen in a number of other diseases.42,43 The effect of psychological function on SLE outcomes requires further investigation.

Social support has also been found to be an important determinant of health status. A cross-sectional study by Sutcliffe and colleagues13 showed that social support, as measured by the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL), was one of the most consistent determinants of health status in their study of 195 patients with SLE. Their study showed that increasing total social support had a positive effect on all of the SF-36 subscales. The authors, therefore, suggest that increasing social support may have the potential to improve overall functioning. A study by Bae and colleagues44 also showed that higher social support influenced health status. However, the patients found to benefit most from social support were those who already possessed social, economic, and health advantages: white patients above poverty level who had health insurance and low premorbid disease activity.

Fibromyalgia/Fatigue

Fibromyalgia is a common rheumatologic disorder that is characterized by widespread pain and fatigue, and may be an important potential confounder in measurement of health status. The prevalence of fibromyalgia in the general population is approximately 2%45; in SLE it has been reported to be much more common, with estimates as high as 23%.46 A recent study of patients with SLE showed a strong association between the number of fibromyalgia tender points and health status as assessed by the HAQ.47 They noted that the number of tender points, and not just the absence or presence of fibromyalgia, was associated with health status in SLE. In a cross-sectional study of 119 outpatients with SLE, Gladman and colleagues showed that SF-36 scores reflected the presence of fibromyalgia, rather than disease activity or damage.48 Fibromyalgia, therefore, is likely a very important determinant of health status in SLE.

An important and common symptom in SLE is fatigue. One study of fatigue in SLE found that 80% to 90% of patients surveyed reported abnormal fatigue49; similar findings have been reported in other studies.50 Fatigue is a symptom that may result from many different processes: active lupus, mood disorders, fibromyalgia, and other comorbid illnesses. It is often difficult to determine the etiology of fatigue in any given case and just as difficult to quantify. Nevertheless, there is evidence that conditions commonly co-expressed in SLE, such as fibromyalgia and depression, may be more important in the development of fatigue than active lupus. In one study of 81 patients with SLE, fatigue was found to correlate moderately or strongly with all components of the SF-36; increased fatigue scores were associated with worse SF-36 scores. Fatigue did not correlate with disease activity or disease damage.51 In another study by Wang and colleagues,52 fatigue was found to be highly correlated with the presence of fibromyalgia and depression. There was no correlation between fatigue and disease activity. The authors of this study conclude that fatigue may reflect a decreased overall coping ability in these patients, rather than active disease itself.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree