Puncture Wounds

Stephen V. Corey

Michelle L. Butterworth

Puncture wounds of the foot are a relatively common problem confronting the physician. A study by Fitzgerald and Cowan (1) noted 887 patients with puncture wounds from a total of 108,648 emergency room visits by children. Reinherz et al (2) attributed 7.4% of all lower extremity trauma that presented to the emergency room over a 12-month period to puncture wounds. In a 3-year period, Corey et al (3) reported that puncture wounds account for 7.8% of patient visits resulting from lower extremity trauma to the emergency room. However, the incidence of puncture wounds reflected in these studies reveals only those patients who presented for treatment. Some patients sustain puncture wounds and never seek medical attention. Unfortunately, many of the patients who are not initially treated do present for treatment after serious complications arise.

Puncture wounds are more prevalent during the warmer months, owing to increased outdoor activities and the number of people who do not wear shoes. The majority of injuries occur between the months of May and October, with the greatest number occurring in July (1,3).

Although many objects can cause puncture wounds, a nail is by far the most common offending object (Fig. 84.1) (1). Other objects may include metal, tree branches, glass, wire, a plastic spike, a rock (1), sewing needles (4,5), wood (toothpicks) (6,7,8 and 9), fish spines (10,11), steak bones (9), coral (12), and graphite (13).

Although the occurrence of puncture wounds is quite common, the treatment rendered is often inconsistent. Traditionally, treatment consisted of superficial cleansing, tetanus prophylaxis, and an oral antibiotic. Discharge instructions usually include foot soaks, weight-bearing as tolerated, and physician follow-up as needed. Unfortunately, this protocol has been shown to lead to complications such as soft tissue infections, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and retained foreign bodies. One report describes streptococcal toxic shock syndrome resulting from a puncture wound of the foot (14).

CLASSIFICATION

The goals of treatment in puncture wounds are twofold: (a) conversion of a contaminated wound to a clean wound, thereby reducing the incidence of infection, and (b) prevention of tetanus. Authors have attempted to outline various treatment recommendations and have devised classification systems to aid the physician with wound evaluation and treatment (1,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 and 23). Resnick and Fallat (15) outlined four categories according to the depth and severity of injury.

Type I: Superficial cutaneous penetration. These are clean wounds penetrating the epidermis and/or dermis, without signs of infection. Cleansing twice daily, non-weightbearing, and weekly follow-up were recommended.

Type II: Subcutaneous or articular joint involvement without signs or symptoms of infection. The offending object penetrates the subcutaneous tissue or joint. Treatment recommendations included anesthesia, sterile prep, wound exploration, cultures, and open packing. Patient instructions included povidone-iodine (Betadine) soaks twice daily, non-weight-bearing, and follow-up twice weekly.

Type IIIA: Established soft tissue infection including pyarthrosis and retained foreign body. It was recommended that these wounds undergo treatment similar to those classified as type II, with the addition of appropriate antibiotic coverage and surgical intervention for persisting symptoms.

Type IIIB: Foreign body penetration into bone. Treatment recommendations included immediate surgical removal of the foreign body, soft tissue and osseous débridement, lavage, open packing, and intravenous antibiotic prophylaxis.

Type IV: Osteomyelitis secondary to puncture wound injury. Antimicrobial intervention and surgical débridement was recommended.

Others (16) have described a classification system with similar treatment recommendations. Krych and Lavery (17) devised a scoring system for wound evaluation that includes wound size, shape, and depth and also accounts for the age of the wound, radiographic presentation, and shoe gear worn at the time of injury. A superficial, clean wound, less than 6 hours old with no radiographic involvement receives local cleansing and observation. The deeper and more contaminated wounds receive a more rigorous treatment protocol consisting of débridement, exploration for foreign bodies, insertion of a drain, prophylactic antibiotics, and possible hospital admission.

Although classification systems can be helpful, there have been no long-term reports reviewing patient outcomes with these treatment schemes. Also, patients must be evaluated on an individual basis. No two patients are alike, and some may not fit into a specific classification system. Patients will present with different signs, symptoms, and complaints, depending on the type and severity of the injury and their medical history.

WOUND EVALUATION AND TREATMENT PROTOCOL

The goal in a patient with an initial presenting puncture wound should be providing adequate inspection with minimal tissue damage, based on the history and physical findings. A number of physicians (1,18,19,22,23,24,25 and 26) have agreed that an aggressive protocol consisting of débridement, probing, removal of foreign bodies, and irrigation is warranted to avoid complications. However, others (27,28) advocate a less aggressive, noninvasive treatment protocol, owing to the fact that the incidence of infection after sustaining a puncture wound is lower than what has been reported because not all patients with puncture wounds seek medical attention.

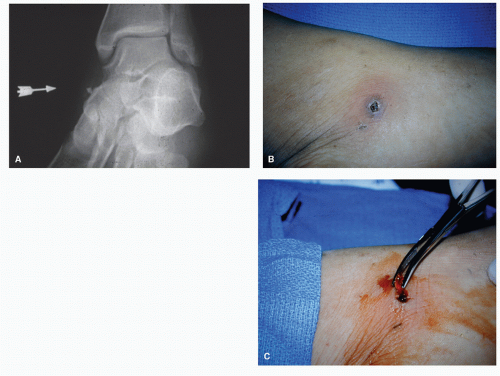

Figure 84.1 Two radiographs, in different planes, provide information on the location and depth of this nail, medial and plantar to the first metatarsal. |

In one study (27), it was reported that only 79 out of 156 patients with puncture wounds came to the attention of a physician. Of these, there were 10 infections, 9 of which were seen by a physician. Counting only the wounds seen by a physician, the infection rate was 11.4%; however, when all the wounds are included, the infection rate decreased to 6.4%.

Although Schwab and Powers (28) reported a complication rate of 11.9% for plantar puncture wounds, they advocated conservative therapy consisting of superficial cleansing and non-weight-bearing for 24 hours in healthy adults presenting within 24 hours of the injury. They concluded that only patients with symptoms persisting beyond 24 hours after injury were at high risk for developing complications.

A more aggressive treatment protocol has been found to reduce the chance of adverse sequelae. This consists of a thorough débridement, wound exploration, removal of foreign bodies and debris, high-pressure irrigation, closely monitored follow-up, and local wound care. Corey et al (3) have used this treatment protocol in 278 patients, with an infection rate of 0% in the absence of retained foreign bodies. In two cases, foreign bodies remained and infection resulted. This emphasizes the importance of ample inspection, which allows the removal of foreign debris with minimal tissue damage.

HISTORY

The patient history is an important part of the initial evaluation and includes questions regarding the characteristics about the penetrating object and the shoes worn at the time of the injury. Factors to consider are the type of object, condition of the object (clean, dirty, rusty, etc.), and the approximate size of the object, including the depth of penetration. If there is a question concerning the depth of penetration, clinicians should use bleeding at the time of the injury as their guide. In general, wounds that have had no signs of bleeding can be considered superficial. It is also important to be aware of the environment in which the injury occurred, such as indoors, in water, or soil. Knowledge of the environment alerts the physician as to the species of organisms that may be present in the wound.

Organisms found in the wound originate from either the normal bacterial flora of the skin or from the penetrating object itself. Staphylococcus aureus and other gram-positive organisms are the most common pathogens encountered (25,29,30). Injuries that occur in swimming pools, lakes, or oceans can become infected with unusual organisms such as Aeromonas hydrophila, Mycobacterium marinum, and Vibrio sp. (29).

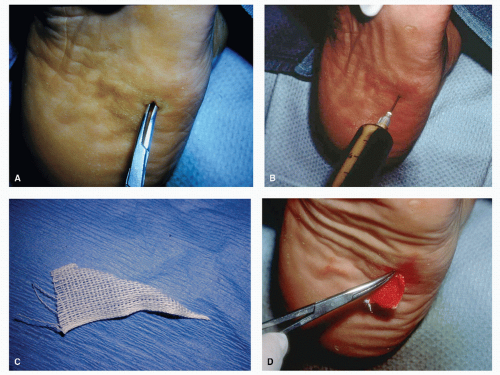

The type of shoes worn at the time of injury can be important in the treatment of puncture wounds (Fig. 84.2). Pieces of clothing and shoes can be forced into the wound during the initial insult and result in a retained foreign body. Tennis shoes have been shown to serve as a source of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (25,30,31,32 and 33). Osteomyelitis secondary to this organism has been noted following puncture wounds (25,30,31 and 32). In addition, people wearing sneakers at the time of injury are more likely to develop osteomyelitis (25,30,34,35).

The time that has elapsed since the injury occurred is also important. The golden period of opportunity is 24 hours or less from the time of the injury. The incidence of infection

increases with the time elapsed following the injury but before treatment, so that earlier intervention is associated with a better prognosis.

increases with the time elapsed following the injury but before treatment, so that earlier intervention is associated with a better prognosis.

Patients with immunocompromised states, such as diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus, peripheral vascular disease, chronic steroid use, or other immunosuppressive medications, may be unable to mount a normal inflammatory response. These injuries may be more significant than they appear because the signs of inflammation and infection may be suppressed.

Tetanus status must also be addressed. If tetanus prophylaxis is inadequate, tetanus toxoid or tetanus immune globulin (TIG), or both, should be administered.

INITIAL PATIENT EVALUATION

The neurovascular status of the involved extremity is first evaluated because the patient’s foot is anesthetized during the examination of the wound. The puncture wound itself is then critically assessed. The physician should try to determine the depth and possible anatomic structures invaded, including muscle, tendon, bone, joint, vessels, and nerves, as well as the presence of any structural damage.

IMAGING MODALITIES

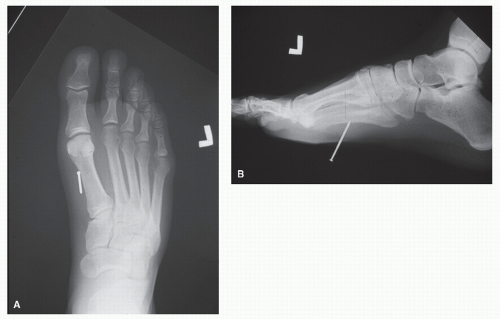

Radiographs should be performed on all patients sustaining puncture wounds, regardless of the subjective severity. Radiographs are not only used in an attempt to reveal retained foreign bodies but also may demonstrate osseous injury that may be caused by the penetrating object. If radiographs do reveal a foreign material, the location, orientation, and depth of the foreign debris can usually be determined by using multiple views. Osseous and joint involvement may not initially be evidenced on radiographs. Obtaining baseline radiographs will also be helpful for comparison should one suspect a later problem. The physician will be able to assess the presence of fractures and joint effusions; however, there is typically a radiographic delay of up to 14 days for the appearance of osteomyelitis.

Failure to perform radiographs has been cited as the reason for failing to recognize up to 38% of foreign bodies in one series of patients (36). However, not all foreign bodies will be visible on radiographs. All metal and approximately 96% of all glass fragments are visible on standard radiographs (Fig. 84.3) (36). A common misconception is that glass must be leaded to be radiopaque. However, it has been shown that all glass is visible radiographically because the density of glass is greater than that of the surrounding tissues (37). Results after testing 66 types of glass revealed that the presence of heavy metals or pigments was not required for radiopacity (38). Fragments as small as 2 mm were discerned when superimposed on bone and 0.5 mm when unobscured.

Some objects, such as wood and plastic, are very difficult to visualize on standard radiographs. Authors have described the possible use of other modalities such as xeroradiography (39,40), ultrasonography (41,42,43 and 44), computed tomography (44,45,46 and 47), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (44) as an aid for assessing the presence and locating foreign bodies. Ultrasound would be the preferred method followed by MRI if suspicion warrants its utilization (33,44).

WOUND EXAMINATION

A complete wound evaluation consists of thorough inspection, débridement, and irrigation. To perform these procedures appropriately, anesthetizing the area is warranted. A posterior tibial nerve block can be performed because most

injuries are on the plantar surface of the foot. Occasionally, an additional regional block may be needed for complete anesthesia. The local anesthetic should not be infiltrated in the immediate area of the wound owing to the risk of spreading contaminated material. The wound is initially cleansed superficially with an antiseptic solution such as povidone-iodine and sterile saline. After this initial superficial cleansing, the remainder of the examination should be performed under sterile conditions.

injuries are on the plantar surface of the foot. Occasionally, an additional regional block may be needed for complete anesthesia. The local anesthetic should not be infiltrated in the immediate area of the wound owing to the risk of spreading contaminated material. The wound is initially cleansed superficially with an antiseptic solution such as povidone-iodine and sterile saline. After this initial superficial cleansing, the remainder of the examination should be performed under sterile conditions.

Examination includes evaluation of wound location, depth, and integrity of the surrounding structures. Initially, débridement of necrotic soft tissue and small stellate, dysvascular flaps is performed to ensure adequate drainage and to decrease the potential for infection. A small linear incision can be used at the puncture wound site to allow for ingress and egress of fluid during irrigation (Fig. 84.4). Some authors (2,48) recommend “coration,” which consists of excising the epidermal edges around the wound to facilitate deeper inspection and cleansing, as well as to reduce the risk of an epidermal inclusion cyst forming.

The wound is then dilated with a hemostat to gain exposure. A blunt object is used for dilation so that overzealous probing does not create a new tract. A probe may be used to determine the depth and course of the wound, the anatomic structures involved, and assist in identifying retained foreign bodies. One may listen and feel for the blunt probe to come into contact with an object. Prolonged and destructive probing of the wound is not recommended owing to the increased potential for additional soft tissue damage and the possibility of driving any retained foreign body deeper into the wound. If difficulty is encountered during retrieval of the foreign material, a more formal exploration should be continued in the operating room with the possible use of fluoroscopy with needle localization for assistance.

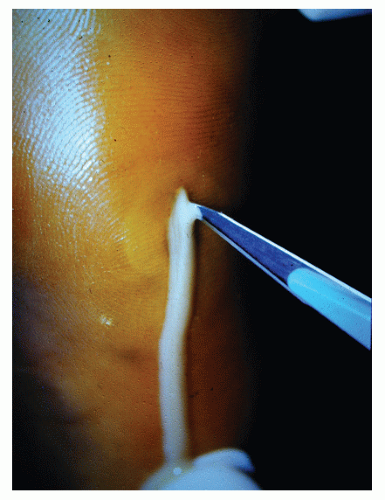

The physician should note any drainage from the wound. The type, color, amount, and consistency of the drainage should be evaluated (Fig. 84.5). Any evidence of purulence necessitates aggressive treatment including débridement and antibiotics. Cultures should be obtained on those wounds with clinical signs of infection, such as surrounding cellulitis, lymphangitis, and purulent drainage.

Figure 84.5 A stream of thick, white purulence is expressed from this 4-day-old puncture wound on initial incision and compression of the area. |

Once exploration and débridement are complete, irrigation is the next critical step. High-pressure irrigation encourages mechanical liberation of debris and cleanses the wound with minimal soft tissue damage. This process can be accomplished with a large syringe and an 18- to 20-gauge blunt tip needle or angiocath (48). If irrigation is performed in the operating room, a pulse lavage apparatus may be employed. Although there are no clinical trials demonstrating the efficacy of highpressure irrigation in puncture wounds of the foot, some authors have described its effectiveness on decreasing contamination in traumatic wounds (48,49).

Copious irrigation is performed with sterile saline. The use of an antiseptic solution in the irrigant is not necessary and can cause irritation of the tissues, especially if extravasation occurs. The wound may appear erythematous in subsequent evaluations as a result. Irrigating solutions impregnated with antibiotics may also be used, but again, they are not necessary. It is the mechanical properties of irrigation, not the antibacterial effect of the solution, that are most important.

Following probing and irrigation, the wound is packed open with a sterile Penrose drain, rubber band, or plain packing, such as Nu Gauze, to allow for adequate drainage and to prevent the wound from closing prematurely. A dry, sterile dressing is then applied. This treatment protocol prevents rapid epithelialization or premature closure of the wound. Allowing the wound to heal from inside out decreases the risk of serious complications. When wounds are allowed to epithelialize within 24 to 48 hours, organisms may harbor inside. With débridement, irrigation, follow-up, and local wound care, most puncture wounds heal satisfactorily. A non-weight-bearing status may prove more comfortable to the patient. Soaking of the foot has not demonstrated any beneficial effects and in fact may lead to potential complications.

Antibiotics should be prescribed based on the clinical findings. Grossly contaminated wounds or those that present with signs of infection should be treated with antibiotics. Antibiotic coverage should also be considered for patients with compromised immune status, regardless of the appearance of the wound. Antibiotics should be prescribed based on the most likely organisms to be present in the wound. The first followup visit usually occurs in 3 to 5 days. Patients must understand that follow-up is critical for continued evaluation of the wound.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree