Chapter 30 Psychopathology, Neurodiagnostic Testing, and Imaging

Classification of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The central nervous system (CNS) is more commonly involved than either the peripheral or autonomic nervous systems. An NP event may reflect either a diffuse disease process (e.g., psychosis, depression) or focal process (e.g., stroke, transverse myelitis), depending on the anatomic location of the injury. In 1999 the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) research committee produced a standard nomenclature and case definitions for 19 NP syndromes that are known to occur in patients with SLE.1 For each of the 19 NP syndromes, potential causes other than SLE were identified for either exclusion or recognized as an association, acknowledging that definitive attribution is not possible for some clinical presentations. The identification of other non-lupus causes for NP events is important and has not been adequately addressed in previous classification systems. Specific diagnostic tests were recommended for each syndrome. Although developed primarily to facilitate research studies of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus (NP-SLE), the ACR case definitions also provide a practical guide to the assessment of individual patients with SLE who have NP disease.

Frequency and Attribution of Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

The overall prevalence of NP disease has varied between 37% and 95% even when using the ACR case definitions.2–6 The most common are cognitive dysfunction (55% to 80%), headache (24% to 72%), mood disorders (14% to 57%), cerebrovascular disease (5% to 18%), seizures (6% to 51%), polyneuropathy (3% to 28%), anxiety (7% to 24%), and psychosis (0% to 8%). The frequency of other NP syndromes is less than 1% in most studies, emphasizing the rarity of many NP events in patients with SLE.

The attribution of NP events to SLE or non-SLE causes remains a challenge, given the absence of a diagnostic gold standard for most of the syndromes. Thus attribution is determined on a case-by-case basis of exclusion using available clinical, laboratory, and imaging data. For each NP syndrome, the ACR case definitions1 provide a list of exclusions and associations, the presence of which may indicate a complete or contributing etiologic alternative other than SLE. Using these and other factors,2 including the temporal relationship between the onset of the NP event and the diagnosis of SLE, recent studies have reported that approximately 66% of all NP events in patients with SLE may be attributed to factors other than lupus.4,7 Regardless of attribution, the impact of cumulative NP events in patients with SLE is evident from the significant reduction in virtually all domains of the short form (SF)-36, a self-report, health-related, quality-of-life instrument.4,7

The substantial variability in the prevalence of NP events may represent inherent differences among study cohorts or a bias in data acquisition. None of the individual NP manifestations is unique to lupus, and some occur with comparable frequency in the general population2 and in patients with other chronic rheumatic diseases.8 Thus in research study design, the inclusion of control groups is critical to determine whether the prevalence of NP disease in patients with SLE is in excess of that found in the general population and in other diseases.9 Because of the rarity of some NP syndromes (<1%), multicenter efforts will be required to study these. Non-SLE factors may likely contribute to a substantial proportion of NP disease in patients with SLE, particularly the softer NP manifestations such as headache, anxiety, and some mood disorders.

Psychiatric Disorders

Prevalence estimates of psychiatric disorders in SLE vary widely.10 Consistent relations with other SLE manifestations have been lacking, and generalized psychosocial stress is acknowledged as an important factor.11 Studies of psychiatric disorders in SLE have been hampered by methodologic problems that include selection bias, variations in case ascertainment (e.g., chart reviews, screening instruments, standardized diagnostic interviews), different observation and follow-up periods, failure to account for social and cultural variables, uncertainties regarding psychiatric illness predating SLE, and inadequate comparison groups. Studies including chronic disease control groups, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), report comparable prevalence and types of psychiatric disorders,8 although these comparable factors do not detract from the importance of recognizing and managing psychiatric disorders in SLE. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV), published in 1994 by the American Psychiatric Association, still serves as the basis for the current ACR case definitions1 describing the psychiatric manifestations of NP-SLE. Importantly, as recognized in DSM-IV, no assumption has been made that states that each category of mental disorder is a completely discrete entity; rather, specific diagnostic criteria included in DSM-IV are meant to serve as guidelines to be informed by clinical judgment. The ACR NP-SLE case definitions1 include in its taxonomy acute confusional state, anxiety disorder, mood disorders, and psychosis, all of which are consistent with the DSM-IV classifications and are discussed in the text that follows. The concept of cognitive dysfunction, also operationalized in the ACR NP-SLE case definitions, is discussed later in this chapter.

Acute Confusional State (Delirium)

Acute confusional state in the ACR case definitions1 is synonymous with the term delirium, as used in DSM-IV and the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9), and also with the term, encephalopathy, which is often preferred by neurologists. It encompasses a state of impaired consciousness or a level of arousal characterized by reduced ability to focus, maintain, and shift attention and is accompanied by disturbances of cognition, behavior, and mood or affect. Other features include disturbed sleep-wake cycles and changes in psychomotor behavior, of which hyperactivity is most easily recognized and lethargy may mask other symptoms.

Incidence and prevalence estimates of delirium in the general population share many of the methodologic problems of NP-SLE previously described. Among older patients, estimates of the incidence of delirium during hospitalization vary from 3% to 42%, whereas estimates of the prevalence of delirium on admission vary from 11% to 33%.12 Prevalence estimates for delirium among patients with SLE have been lower and in the range of 4% to 7%.2,4,5 Brey and colleagues3 found no cases of delirium when they used the ACR case definitions1 to examine the point prevalence of NP-SLE syndromes in 128 subjects. Distinguishing delirium from persistent cognitive impairment can require an informant’s history of acute onset of new symptoms. Because fluctuations in attention and level of arousal are key features of delirium, careful observation over time can be necessary. Mental status screening assessments conducted only once may misdiagnose delirium as dementia. The attribution of delirium to SLE is challenging because doing so requires the exclusion of CNS infection, metabolic disturbances, substance-induced or drug-induced (or withdrawal) delirium, and any mental or neurologic disorder unrelated to SLE.1 Regardless of its cause or attribution to SLE, delirium is more likely to occur if preexisting cognitive impairment can be associated with an increased risk for dementia. Thus the presentation of delirium in a patient with SLE indicates a need to examine the patient for preexisting cognitive impairment and for careful follow-up of possible residual cognitive or functional impairments.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety and depression are common in SLE, occurring in 24% to 57% of patients,2–6 although uncertainty about their causes and attribution is often present. Anxiety disorders represent prominent generalized anxiety or panic attacks or obsessions or compulsions that result in significant distress or impaired function. However, it is extremely challenging to attribute an anxiety disorder to physiologic changes of the CNS caused by SLE rather than the side effects of a pharmacologic treatment or an adjustment reaction in which anxiety symptoms are the result of the stress of having a medical condition. Although one might presume that clinically significant anxiety symptoms resulting from an adjustment disorder are common in SLE, no studies have directly addressed this presumption.

Variable prevalence estimates of anxiety disorders in SLE have been reported. A retrospective chart review of 518 patients from Hong Kong in which only two cases of anxiety disorders were identified13 is one extreme. Another study reported 56% lifetime prevalence of phobia and 12% lifetime prevalence of generalized anxiety in patients from Iceland.14 More typical are prevalence estimates in the range of 7% to 8%,5 although these estimates may not exceed those of the general population. In more recent studies using the ACR case definitions,1 Brey and colleagues3 reported a 24% prevalence of anxiety disorders in 128 patients, and Sibbitt and colleagues6 reported a 21% lifetime prevalence in 75 patients with symptom onset before age 18 years who were followed for an average of 6 years. Further definitive epidemiologic studies of psychiatric manifestations in SLE using current diagnostic methods are necessary as comparisons among studies remain hampered by case ascertainment differences, possible population base rate differences, and possible cultural and genetic differences in the populations sampled.

As with data derived from self-report instruments for mood and anxiety symptoms, distinguishing between anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders is important. Based on a prospective study of 23 patients with SLE, Ward and colleagues15 found that anxiety symptoms varied with global SLE disease activity, whereas Segui and colleagues16 reported that a decline in anxiety symptoms accompanied the change from active to quiescent disease, suggesting that distress resulting from active lupus may increase anxiety symptoms. Ishikura and colleagues17 found that anxiety symptoms were associated with the lack of knowledge about SLE and its management at the start of treatment, suggesting that improved knowledge about SLE and its treatment may reduce the likelihood of future emergence of anxiety symptoms.

Mood Disorders

Mood disorders as described in the ACR case definitions for NP-SLE1 include the equivalent of DSM-IV major depressive disorder (MDD), one or more episodes of 2 or more weeks of depressed mood or loss of interest, plus at least four other symptoms of depression. Mood disorder with depressive features is also included, compatible with the DSM-IV dysthymic disorder (i.e., at least 2 weeks of depressed mood for more days than not, plus additional symptoms of depression not meeting the criteria for MDD). In addition, mood disorders with manic and mixed features are included, compatible with DSM-IV bipolar disorder (i.e., depressive episodes accompanied by manic, mixed, or hypomanic episodes). Such conditions are distinct from substance-induced mood disturbances and from adjustment disorders with depressed mood (i.e., symptoms of depressed mood, tearfulness, and feelings of hopelessness within 3 months of an identifiable precipitating stressor), neither of which has been examined in detail in SLE.

Patten and colleagues noted that “Young people with long-term medical conditions have a particularly high prevalence of mood disorders,”18 and studies using the ACR case definitions1 have suggested this to be the case among patients with SLE. Ainiala and colleagues19 reported a 43% prevalence of mood disorders in their sample of 46 patients. Brey and colleagues3 reported major depressive-like episodes in 28% and mood disorders with depressive features in 19%, whereas manic (3%) and mixed (1%) features were uncommon. Lower prevalence estimates have been reported by Sanna and colleagues (16.7%),5 by Hanly and colleagues (14.4%),4 and by Mok and colleagues (6%).13

A recent study of 111 newly diagnosed patients with SLE illustrates the prevalence of the mood disorders issue. Even when using a screening instrument with fewer somatic items, Petri and colleagues20 reported an 8.1% prevalence of mood disorder, according to ACR case definition criteria, but a 31% prevalence of depression on the basis of their screen instrument. Using the latter, they found depression to be associated with the presence of fibromyalgia and with poorer cognitive test performance, although not with other demographic or clinical characteristics. Associations between depression and other SLE manifestations have been found by some21 but not by others.17 Small samples and differing methodologies make comparisons difficult. Attribution of anxiety and mood disorders to a CNS manifestation of SLE is difficult. For example, in another sample of 111 patients, Hanly and colleagues4 attributed only three of nine cases of major depression to SLE alone, whereas the remaining cases were attributed either to non-SLE factors or to both. Evidence for a biological basis primarily comes from potential immune system effects on mood states,22 although complex associations with demographic and social factors, knowledge of disease, social supports, and adjustment to a chronic, unpredictable condition with significant potential morbidity must also be recognized.17 A disabling autoimmune disease with an unpredictable course is not unique to SLE and is perhaps why patients with RA also frequently experience psychiatric symptoms and respond similarly to screening scales of depression and anxiety symptoms.8

Psychosis

Although rare, psychosis (DSM-IV, 293.0) is a dramatic NP-SLE manifestation that must be carefully distinguished from a primary psychiatric illness, delirium, and substance-related disorders. Psychosis in the context of NP-SLE can be associated with predominant symptoms of delusions (DSM-IV, 293.81) or hallucinations (DSM-IV, 293.82) or both, which must be distinguished from delirium. Psychotic features may also be associated with the use of corticosteroids23 and antimalarial drugs,24 although substance abuse must also be considered. Prevalence estimates of psychosis vary but have been as high as 8% of patients with SLE.2–6

Cognitive Function in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Cognition is the sum of mental processes that result in observed behavior. Although conceptually distinct, functional domains of cognition are often used; many, such as attention, memory, or language, are too broad to have simple and well-defined neuroanatomical bases. Cognitive dysfunction may be limited to aspects of particular domains of function or may be more diffuse. Either can result in a relatively global impairment of cognition, although the construct of dementia, a case conceptualization based on Alzheimer disease, has only limited application to SLE. The ACR case definitions1 acknowledge that even relatively mild cognitive problems still can have significant functional impact for patients with SLE, and recent studies have increasingly emphasized the importance of sensitivity in the detection of cognitive impairments in SLE.

Self-reported cognitive difficulties remain a primary means of identifying patients with possible SLE-associated cognitive dysfunction, but reliance on patients’ reports is problematic. Although cognitive complaints are common in SLE, they are also common in many other clinical contexts, and their association with objective cognitive impairment and specific neuropathologies remains unclear. The Cognitive Symptoms Inventory (CSI) questionnaire was designed to assess self-perceived ability to perform everyday activities in patients with rheumatic disease.25 Higher scores, suggesting greater impairment, have been found for patients with SLE compared with patients with RA,8 and the CSI may be useful for identifying patients with SLE who are at risk for cognitive impairment.26 However, validation of subjective complaints with objective measures of cognitive performance is largely lacking. Kozora and colleagues27 reported increased subjective complaints and objective evidence of impairment among patients with NP-SLE, as well as an association between subjective complaints and impairment among patients with NP-SLE only. However, many of their NP-SLE samples included patients with mood disorders and headache, and strong associations were also found between cognitive impairment and self-reported depression, pain, and fatigue. A large body of literature demonstrates the association of subjective cognitive complaints with stress and disorders of mood and makes distinction among these issues difficult. Indeed, in an 8-week psychoeducational group intervention program for 17 patients with SLE who had subjective cognitive complaints, Harrison and colleagues28 reported improvements not only in CSI scores and memory test performance but also in self-reported depressive symptoms.

Recognizing and documenting mild yet significant SLE-associated cognitive impairment remains challenging. A review of 14 cross-sectional studies of cognitive function in SLE revealed cognitive impairment that was considered subclinical in 11% to 54% of patients.29 The ACR case definitions1 require that cognitive dysfunction be evident on neuropsychological testing with the interpretation based on normative data appropriate for age, education, sex, and ethnic group, wherever possible. Such neuropsychological assessment typically involves a battery of tests that examine various domains of cognitive functioning—those either identified as problematic by the patient or considered likely to be problematic on the basis of the underlying medical condition, in this case, SLE. The ACR case definitions1 identify eight domains of cognitive functioning of particular importance: (1) simple attention, (2) complex attention, (3) memory, (4) visual-spatial processing, (5) language, (6) reasoning and problem solving, (7) psychomotor speed, and (8) executive functions. At least one of these domains must be affected, although distinctions among them are blurred as with most such classification systems. For example, psychomotor speed, the speed and efficiency with which mentally demanding tasks can be completed, may well influence a patient’s performance on tasks that examine domains such as memory, language, visual-spatial processing, or executive functions. These latter domains, themselves, each have numerous overlapping subcategories of functions. Nonetheless, the ACR case definitions1 provide a valuable framework that allows operationalization of domains of cognitive functioning and standardization of the content of the neuropsychological assessment.

Standardized neuropsychological test batteries and predetermined thresholds, such as performance as little as one standard deviation below the mean of the general population,27 allow for an actuarial approach to identifying cognitive impairment. Although this approach has the benefit of standardization for population-based studies, it is not ideal when examining complex multidimensional constructs of cognition, as is required for individual patients in clinical practice. A patient with above-average education and functional level may test at a normal (i.e., average) level, compared with the general population; even for them, the average performance represents a decline in ability; but the opposite may well be true for those with lower premorbid functioning. Although the common practice of combining individual test scores into index variables can serve to mask deficits in specific areas of cognitive functioning, the opposite can occur when multiple tests are simultaneously considered30 with the result that prevalence estimates of impairment are significantly inflated. Attempts to correct for demographic factors do not fully address issues of sensitivity and specificity of classifications of impairment,30 and standardization samples differ significantly across various neuropsychological tests. These issues are well illustrated in the study of childhood-onset SLE by Williams and colleagues.31 For clinical decision making, an individualized approach to patient assessment that accounts for psychosocial, demographic, and clinical characteristics is necessary.

Various neuropsychological testing methods have been used in patients with SLE, and prevalence estimates for cognitive impairment have varied with the threshold for impairment and the clinical and demographic characteristics of the samples. Although many patients are now recognized as having at least mild cognitive impairment even without recent overt signs of CNS disease, prevalence estimates of cognitive impairment determined via neuropsychological assessment have continued to vary from 7% to 80% of patients,2–631 using the ACR case definitions.1 Clearly, the selection of control groups for comparison and the criteria used for defining impairment remain critical issues,31 and the need for studies of larger, longitudinal, multicenter efforts remains.

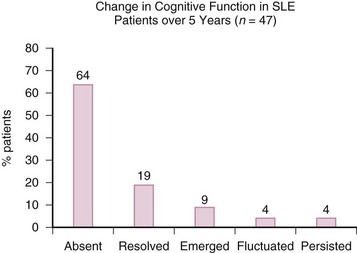

Prospective studies to date have not generally found increasing point prevalence of cognitive impairment,32,33 although most predate the ACR case definitions.1 In a 5-year prospective study of 70 patients, Hanly and colleagues32 found a decline in overall cognitive impairment from 21% to 13% with most either never impaired or with resolution of cognitive impairment and only a minority demonstrating emergent, fluctuating, or persistent impairment (Figure 30-1). Similar relatively benign courses of cognitive impairment have been reported in other prospective studies ranging from 233 to 5 years’ duration.34 However, Hanly and colleagues32 found that patients with clinically overt NP-SLE at any time had a decline in memory test performance over 5 years when compared with patients without such a history. Although the identification of isolated subclinical cognitive impairment may have important current clinical implications, the occurrence of clinically overt NP events may have greater relevance for accumulating cognitive impairment over time. Deterioration may occur in select individuals, but little current evidence suggests that it is inevitable or profound.

The pattern of cognitive impairment typically observed in patients with SLE is neither specific nor unique. Impairments include slowed information-processing speed, reduced working memory, and executive dysfunction (e.g., difficulty with multitasking, organization, and planning), which is a pattern associated with pathologic impairments affecting subcortical brain regions. Impairment is usually observed on tests of immediate memory or recall, verbal fluency, attention, information-processing efficiency, and psychomotor speed. Although Leritz and colleagues35 reported that 95% of their sample had a subcortical pattern of cognitive dysfunction when screened for cognitive impairment, few actually scored in a range representing impairment on the instrument used. Most problems were on serial sevens tasks that place demands on attention, working memory, and mental tracking. A similar subcortical pattern of cognitive impairments is seen in those with multiple sclerosis (MS), and Shucard and colleagues36 found that patients with SLE and MS had similar impairments and compensatory strategy use when performing a test requiring information-processing speed and intact working memory.

The common findings of reduced information-processing speed and complex attention deficits in patients with SLE has led to increased interest in and the use of computerized neuropsychological assessment methods as potentially sensitive, reliable, and efficient methods of identifying cognitive impairment among patients with SLE. A study using the recommended ACR neuropsychological test battery in conjunction with a computerized test of cognitive efficiency, the Automated Neuropsychological Assessment Metrics (ANAM),37 identified cognitive impairment in 78% of patients with SLE, making it one of its most commonly identified NP-SLE syndromes.3 The identified frequency of cognitive impairment using the ANAM was 69% in these adult patients with SLE3 and 59% in a study of childhood-onset SLE.38 In another study of adult patients with SLE studied within 9 months of diagnosis, Petri and colleagues39 found cognitive impairment in 21% to 61% of cases, depending on the stringency of the definition of impairment. Hanly and colleagues9 also found a range of cognitive impairment ranging from 11% to 50%, compared with locally recruited healthy control subjects, again depending on the stringency of the decision rules. However, this frequency was comparable to that observed in patients with RA (9% to 61%) and lower than in patients with MS (20% to 75%) from that same center. Such findings raise some concerns regarding the presumed causes of deficits detected by computerized tests such as ANAM; these measures may not distinguish between nonspecific reduction of sensorimotor efficiency and more specific abnormalities in higher cognitive functions such as working memory and executive abilities. Although computerized tests such as ANAM seem sensitive to reduced cognitive efficiency, this sensitivity may arise from many causes and cannot be used to determine impairment of specific domains of cognitive abilities or be used as a substitute for formal neuropsychological assessment. Future studies are needed to determine the role of computerized testing in screening for cognitive impairment in patients with SLE, as well as its value in the evaluation of changes in cognitive performance over time.

Etiology of Cognitive Impairment in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Cognitive Function, Global Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity, and Overt Neuropsychiatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Although cognitive impairment may be viewed as a distinct subset of NP-SLE, cognitive functioning may also serve as a surrogate of overall brain health in patients with SLE, one that may be affected by a variety of factors including other NP syndromes. Chronic medical illness provides many potential generic causes of subtle cognitive dysfunction (Box 30-1). Determining whether chronic illness causes or contributes to cognitive dysfunction in patients with SLE requires careful consideration on an individual basis, but the accumulated evidence suggests that such explanations alone are insufficient to account for the entire overall burden of cognitive impairment in SLE. Not surprisingly, the prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in patients with past or current NP-SLE is greater than in those with no such history. However, the relationship between cognitive dysfunction and overall disease activity remains unclear. Some studies40 have found that patients with active disease had poorer performance on neuropsychological tests than patients with inactive or mildly active disease. Cumulative damage, together with hypertension, antiphospholipid antibodies, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings (described in further detail in the following text) have also been associated with greater cognitive impairment.41