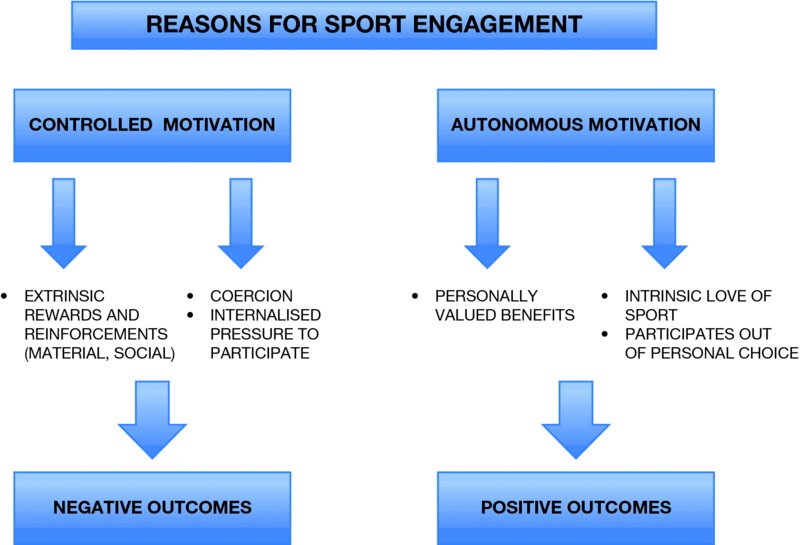

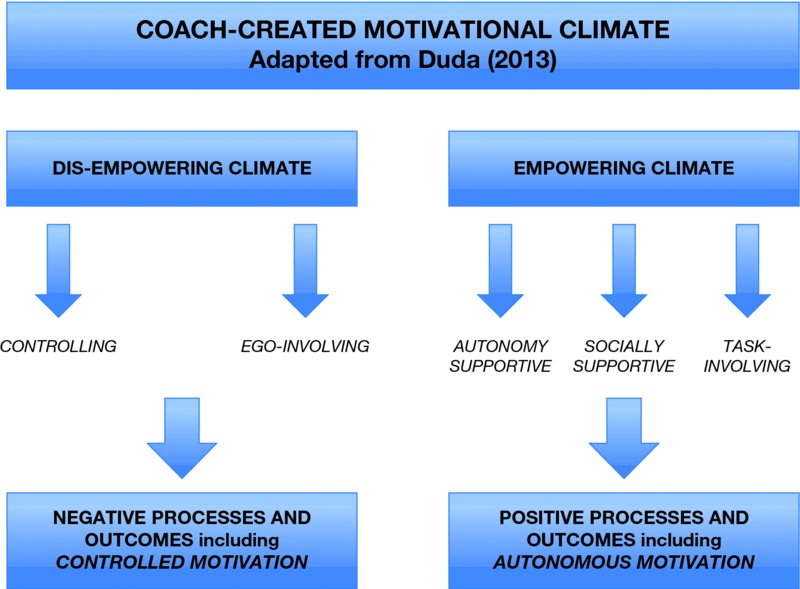

Chapter 3 Joan L. Duda1 and Saul Marks2 1School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, UK 2Division of Consultation Liaison Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada The field of sport psychology is concerned with the psychological factors and social psychological processes impacting sport performance and participation of athletes and athletic teams at all competitive levels. Sport psychology, as a scientific discipline and area of applied practice, has grown significantly over the past 50 years. The number of and membership comprising professional organizations in sport psychology around the world (e.g., the International Society of Sport Psychology; the Association of Applied Sport Psychology), and scientific publication outlets for research in this area (e.g., the Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, Psychology of Sport and Exercise), have increased. The relevance of the field to maximizing training and competitive performances is now more widely recognized and accepted. Athletes and their coaches are more aware that the regular practicing of psychological techniques and the systematic development of psychological skills should go “hand in hand” with physical training and physical preparation for competition. It is recommended that athletes formulate and consistently rehearse (in training) and apply (in competition) preperformance and postperformance routines that are comprised of physical (e.g., when at the free throw line, several bounces of the basketball and then a deep breath before shooting) and psychological (e.g., “seeing” and “feeling” where the shot will go and committing to that goal) components. Research in sport psychology also speaks to the importance of the coach-created environment to the quality of athletes’ sport engagement and the likelihood of their maintaining participation. Theory- and evidence-based training programs now exist, which ‘set the stage’ for more positive and adaptive (and less negative and maladaptive) exchanges between athletes and their coaches and other significant others in their lives, such as parents. Sports psychiatry has often been a misunderstood and under-serviced area of medicine in the world of sport. Sports psychiatry made its defining entry into the scientific literature in May 1992, in the American Journal of Psychiatry, in a paper titled “An Overview of Sport Psychiatry” by Dr. Daniel Begel. As a medical specialty, psychiatry has been recognized since the middle of the nineteenth century; however, the interface between psychiatry and the world of sport has often been misunderstood. Dr. Begel defined sport psychiatry as the implementation of psychiatric knowledge and treatment methods to the world of sport. Elite athletes are subject to massive somatic, social, and mental stress. Although the public has great interest for athletic achievements, the emotional strains brought on by such “heroic moments” until the last two decades have not been considered in the scientific literature. Over time, there have been more and more papers in research journals and presentations at international scientific conferences on the subject. The field, however, has suffered from a lack of controlled studies (and data) on incidence, phenomenology, and treatment of psychiatric disorders in athletes. In this chapter, we summarize some of the latest findings stemming from the fields of sport psychology and sport psychiatry, which relate to female athletes’ functioning within the sport setting, their psychological and physical health, and overall well-being. We conclude by calling for integrative research approaches that can inform evidence-based and interdisciplinary practice in optimizing the psychology of female athletes and addressing the mental health issues faced by them. Sport psychology emphasizes the importance of helping athletes learn and become proficient at psychological techniques (such as goal setting, positive self-talk, imagery, the use of focus cues, relaxation, and activation techniques) that can provide them with the skills to more effectively regulate cognitions, emotions, and behaviors during training and competitive events. This is often referred to as “mental skills training” or MST. Although more controlled trials are needed, research has revealed that elite athletes benefit from MST in terms of their performance, confidence levels, concentration capabilities, and attentional focus and/or observed decreases in debilitating anxiety. The goals of MST, however, are assumed to be much broader than performance enhancement per se. The literature indicates that systematic training that results in athletes possessing strong and robust mental skills also can lead to greater health and well-being. Most of the research to date has centered on adult-age athletes, but studies have also demonstrated that younger athletes, such as those climbing the ladder to elite levels, witness positive effects from MST. Indeed, it has been suggested that the ideal time for athletes to be introduced and gain fluency in mental skills is when they are young. In this way, young competitors are more likely to have the “mindset” to exploit their skill progression. They also would be prone to demonstrate resiliency to handle the setbacks that are inevitable as one becomes more “serious” about sport and strives to be competing with better and better opponents. The literature suggests a synergy between the enhanced self-regulation capabilities, which can be developed in athletes via MST and more autonomous reasons for sport engagement. More specifically, when an athlete is more self-regulated, this athlete is more likely to be self-determined. Autonomous or more self-determined reasons include participating in sport out of personal choice and because the athlete truly loves the sport in question. When an athlete volitionally engages in sport because she values the benefits that are derived from participation, then this athlete is also autonomously motivated. Contemporary theories of motivation and research indicate that more autonomous motivation is “quality” motivation. Athletes who have quality motivation are more likely to work hard and work effectively, and their sense of who they are as people (i.e., their self-worth) is less tied to their sport performance. They tend to “keep on going,” even when all is not going well and the extrinsic rewards associated with sport engagement are diminished or no longer exist. Autonomous motivation is predictive of greater sport enjoyment, feelings of vitality, and the tendency to define success in terms of doing one’s best. However, there are nonautonomous reasons for engaging in sport that are indicative of low quality motivation. Some athletes feel “controlled” in terms of why they are participating. They may be involved out of feelings of guilt or coercion; for example, they think they will let someone down (e.g., the coach, their parents) if they quit. Athletes can also participate in sport primarily because of extrinsic reasons (e.g., notoriety, accolades, and financial reward). In either case, someone or something else is “pulling the strings” in regard to reasons for engaging in sport. Controlled motivation is associated with heightened anxiety and a propensity for burnout, fear of failure, contingent self-worth, and intentions to drop out of sport (Figure 3.1). Figure 3.1 Autonomous and controlled reasons for engagement and their implications for positive/negative outcomes in sport A key determinant of whether athletes are likely to exhibit autonomous and/or controlled motivation is the social psychological environment (or motivational climate) created by the coach. Theories of motivation and related research indicate which types of environments are more conducive to quality engagement and which coach behaviors are more likely to lead to controlled reasons for engagement. One important feature of a coach-created environment, which holds significance for athletes’ motivation, is the degree to which it is marked by autonomy support. In essence, autonomy support nurtures and maintains autonomous motivation. Coaches who are autonomy supportive (i) provide their athletes with meaningful choices and solicit their input, (ii) acknowledge the perspective of their athletes, (iii) minimize the use of extrinsic reward and when present, do not use them to control their athletes, and (iv) offer a rationale for requests and recommendations made. Quality or more autonomous motivation is also facilitated when coaches are more task-involving. Task-involving coach behaviors include emphasizing when athletes try hard and exhibit learning and/or performance improvement. Socially supportive coaches also contribute to athletes’ autonomous reasons for sport engagement. A socially supportive coach is one who cares, is there to help when needed, and separates the athlete from the performance. Recently in the literature, autonomy supportive, task-involving and socially supportive coach behaviors have been conceptualized as the building blocks to a more “empowering” climate. In an empowering climate, athletes have a sense of ownership over their engagement and are “free” to grow and develop optimally in and through their sport. An “empowering” climate brings out the best in athletes, whether they are high in confidence or struggling with performance slumps, injury, or some other issue that is negatively impacting their perceptions of ability. Coaches can also exhibit more “disempowering” behaviors that encourage controlled motivation in their athletes. Controlling coaches (i) employ intimidation, (ii) use extrinsic rewards to manipulate athletes to do what they want, (iii) engage in punitive actions, (iv) are authoritarian, and (v) show athletes that their approval is depending on the athlete being compliant and performing well. Ego-involving behaviors by the coach also contribute to a “disempowering” climate and evoke controlled motivation. In an ego-involving environment, coaches emphasize the importance of being the best (showing superiority) over doing one’s best and make it apparent which athletes are considered more able or talented in their eyes. These are the type of coaches for whom “winning is everything and the only thing” with the athletes’ development and welfare considered less important. Research has shown that more disempowering coach-created motivational climates are linked to greater anxiety, lower morale functioning (e.g., as evidenced by cheating), and intentions to drop out. The negative impact of such environments is particularly marked on an athlete who is low in confidence. This finding is of particular relevance to female athletes, who are still more likely to doubt their abilities and have a more fragile sense of self than their male counterparts (Figure 3.2). Figure 3.2 Dimensions and implications of ‘empowering’ and ‘dis-empowering’ climates as conceptualised by Duda (2013) Recent research in sport psychology has indicated that coaches can be trained up to be more empowering/less disempowering. Such a training program entails having coaches understand the how and why of an empowering approach and also become more cognizant of the costs of disempowering environments on athletes’ health and well-being, development, and sustained engagement.

Psychology of the female athlete

Introduction

The importance of mental skills training

MST and implications for athlete motivation

The coach-created environment and athletes’ motivation

Training to change the motivational climate

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree