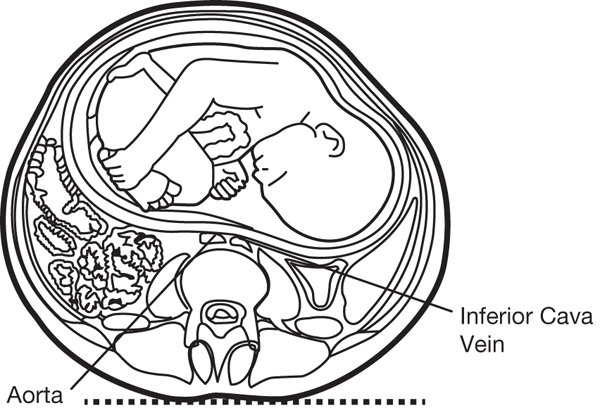

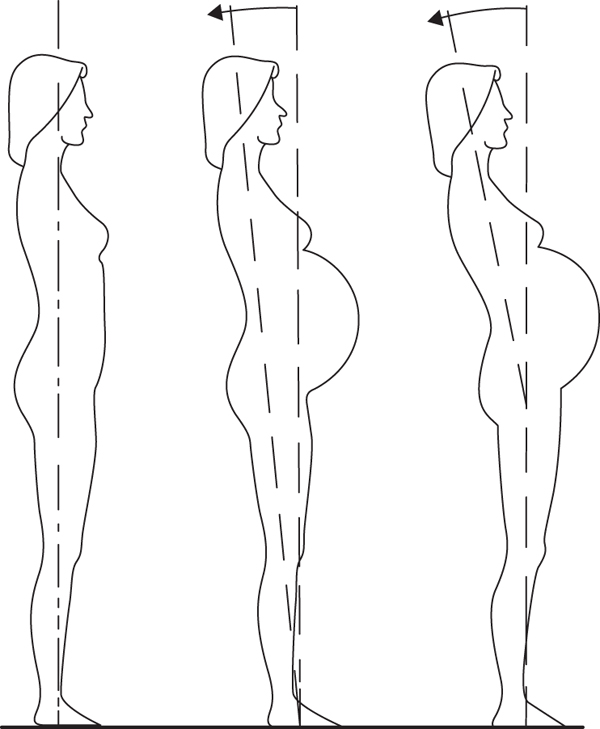

Chapter 12 Ruben Barakat1, Alejandro Lucía2 and Jonatan Ruiz3 1Faculty of Physical Activity and Sports Sciences, Technical University of Madrid, Spain 2Universidad Europea de Madrid, Spain, Instituto de Investigación Hospital 12 de Octubre (i+12), Madrid, SPAIN 3PROFITH “PROmoting FITness and Health through physical activity” research group, Department of Physical Education and Sport, Faculty of Sport Sciences, University of Granada, Granada, Spain Pregnancy is the unique vital process in which a woman’s body control systems are modified to preserve the life of the fetus during its growth and development. Throughout 38 weeks of gestation, a women’s body constantly changes to maintain body balance and biological homeostasis and deliver the baby without maternal or fetal complications. Any disarrangement or imbalance can adversely affect pregnant outcome. But why should we exercise during pregnancy? Is there scientific evidence for a beneficial effect of regular physical activity during the course of pregnancy? Despite pregnant woman being denied the possibility of an active gestation period in the past, there is growing evidence from observational and intervention studies that a woman with no obstetric complications may exercise during pregnancy without any detrimental impacts on maternal–fetal outcome. Fortunately, there is a current tendency toward regular physical activity during pregnancy, and more importantly, physical activity is today considered an important part of routine daily life and the pregnancy period is no exception. Today’s concept of health has changed from the old idea of “absence of disease” to a wider concept that, besides the proper functioning of vital organs (cardio-circulatory, metabolic and hormonal functions), also considers psychological well-being and affective-social human behavior. A sedentary lifestyle can lead to many health complications, and this also applies to pregnant women. Even Aristotle mentioned that “Difficult deliveries are due to a sedentary lifestyle” (Aristotle, C. III b.c.). Indeed, exercise is now known to benefit many aspects of a pregnant woman’s health. For a new pregnancy not to reduce quality of life, we therefore need to find (among the many options that physical activity offers) a way of avoiding a sudden decline in physical activity. Two basic facts should be taken into account: From the start of the first trimester until the end of pregnancy, cardiac output (the product of stroke volume and heart rate) increases by 30% to 40% as a result of an increased heart rate (e.g., from 70 beats/min before pregnancy to 85 beats/min in late pregnancy) and a slight increase in stroke volume. Peripheral vascular resistance diminishes, and this leads to a slight drop in blood pressure. Diastolic blood pressure decreases in the first and second trimester and returns to prepregnancy values in the third trimester. Systolic blood pressure is modified slightly, with a tendency to decrease in the first and second trimester. Possibly the most significant (and most consequential) change during pregnancy is the compression of the inferior cava vein by the gravid uterus. When a woman adopts a supine position, this phenomenon decreases venous return to heart (Figure 12.1). Figure 12.1 Compression of the inferior cava vein. From De Miguel and Sanchez (2001). Among other factors, inferior cava vein compression affects cardiac output and variables related to the circulatory system. Blood volume increases by 45% (∼1800 mL), and this is accounted for by both an increased plasma volume (∼1500 mL) and an increased red cell volume (∼350 mL). This “heme dilution” maintains adequate uteroplacental flow. Changes in the respiratory system cause anatomical and functional alterations. These modifications occur early during pregnancy owing to hormonal effects and the above-mentioned increments in blood volume, and include changes in lung dimensions and capacity as well as inspiratory/expiratory mechanisms. Reduced functional residual capacity accompanied by increased oxygen consumption diminishes the oxygen reserve. The oxygen cost of ventilation also rises owing to an increased workload on the diaphragm. Estrogens and progesterone cause an increase in lung ventilation which gives rise to respiratory alkalosis. However, the acid–base balance is maintained by a compensatory metabolic acidosis mechanism and blood pH values remain around 7.44. Most of these maternal breathing mechanisms are targeted at reducing arterial PCO2 to create a mild alkalosis. This ensures maternal placental gas exchange and prevents fetal acidosis. During pregnancy, normal metabolic processes are altered to accommodate the needs of the developing fetus. The protein contents of the body tissues increase. Carbohydrates accumulate in the liver, muscles, and placenta. In addition, fat deposits appear under the skin, especially affecting the breasts and buttocks, and this is frequently accompanied by increased blood lipid levels, including cholesterol. The pregnant woman’s body accumulates the salts of several minerals that are essential for normal fetal development, that is, calcium, phosphorus, potassium and iron. In addition, hormonal changes promote water retention in the tissues. Maternal weight gain is one of the most obvious changes that occur during pregnancy. Although there is individual variability, a weight increase from before pregnancy to the end of pregnancy of 10–13 kg is considered normal. The factors responsible for this weight gain during pregnancy are provided in Table 12.1. Table 12.1 Maternal weight gain during pregnancy Pregnant women often experience paresthesia and pain in the upper extremities as a result of marked sinking of the cervical lordosis and shoulder girdle, frequently in the third trimester. In effect, an important characteristic of the pregnant body is the arching of the lower back or “hyperlordosis of pregnancy.” This problem was traditionally attributed to the growth of the uterus, but current scientific evidence indicates that the mother offsets the deviation of her center of gravity by moving backward the entire skull-caudal axis (Figure 12.2). Figure 12.2 Deviation of the center of gravity. From De Miguel and Sanchez (2001). Occasionally, the rectus abdominis muscles are separated from the midline, creating a diastasis of variable extension. Sometimes, this phenomenon is so marked that the uterus is only covered by a thin layer of peritoneum, fascia, and skin. The mobility of the sacroiliac joints increases under the control of hormones such as relaxin, and this sometimes causes diffuse pain. Pregnancy is a unique process in which nearly all of the body’s control systems are modified to maintain both maternal and fetal homeostasis. Since regular physical exercise is today an integral part of the recommendations for a healthy lifestyle, the question remains as to whether exercise may have an adverse effect on pregnancy. In theory, physical exercise during pregnancy should significantly challenge both maternal and fetal well-being due to the conflicting physiological demands of pregnancy and exercise. The effects of exercise during pregnancy have been extensively explored. However, the low number of well-controlled and adequately powered randomized controlled trials has meant that evidence has been conflicting. Although there is no general consensus regarding the potential long-term risks of or benefits for the offspring of physically active mothers, most studies report that maternal and fetal well-being are not compromised when exercise intensity is light to moderate. The heart rate in pregnant women is significantly higher during exercise compared with nonpregnant women. For stroke volume, similar results have been reported in pregnant and nonpregnant women. Cardiac output increases peaking between 20 and 24 weeks of gestation and thereafter dropping gradually until the end of pregnancy. This decline in the later stages of pregnancy may be due to changes in peripheral vascular resistance and mechanical obstruction of venous return generated by the pressure of the pregnant uterus. Exercise modifies cardiac output by increasing blood flow to active muscle areas at the expense of decreasing flow to other areas such as the uteroplacental unit. Moderate-intensity physical activity causes a reduction in uteroplacental blood flow of ∼25%, the magnitude of this reduction being more marked at higher intensities. However, the hypothetical risks posed by exercise blood redistribution are offset by maternal–fetal mechanisms, which ensure maternal and fetal well-being during moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. Particularly, the greatest blood flow reduction occurs in the uterine wall so that the flow of oxygen and nutrients through the placenta is adequate, thus maintaining fetal homeostasis. In summary, cardiovascular changes caused by moderate-intensity physical activity during pregnancy do not pose a health risk to the mother and fetus in a healthy pregnancy.

Exercise and pregnancy

Particularities of pregnancy and childbirth

Special features of pregnancy and childbirth

Modifications in pregnant body systems related to physical exercise

Circulatory system

Blood system

Respiratory system

Metabolic processes

Maternal weight gain (grams)

Week 10

Week 20

Week 30

Week 40

Fetus

5

300

1500

3400

Placenta

20

170

430

650

Amniotic fluid

30

350

750

800

Uterus

140

320

600

970

Breast

45

180

360

405

Blood

100

600

1300

1250

Interstitial fluid

0

30

80

1680

Fat deposits

310

2050

3480

3345

Total gain

650

4000

8500

12 500

Locomotor effects

Effect of maternal exercise on pregnant body systems

Cardiovascular and hematological response to exercise

Uteroplacental blood flow response to exercise

Respiratory response to exercise

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree