Cognitive appraisal

According to the stress model, the way your athlete cognitively interprets a situation is affected by their personality and their coping styles. Cognitive appraisal affects stress levels, which can lead to an increased risk of injury. The word cognition pertains to thought patterns and processes. Cognitive appraisal is, therefore, what your athlete thinks about a situation which affects their emotional and behavioural responses. Seeing a situation (or injury during the recovery process) as a challenge (facilitative) as opposed to a threatening situation (debilitative) will positively affect behaviour. Perceptions, facilitative or debilitative, can have an effect on how the athlete feels and behaves during competition or the rehabilitative process. Cognitive appraisal is a dynamic process that can change over time and it is up to you as rehabilitator to help your athlete see the positive challenge of the rehabilitative process.

Interventions

Johnson, Ekengren and Andersen (2005), in a study based on the Williams and Andersen (1998) stress–injury model, were able to design a programme for soccer players who they identified as being at risk of injury. An at-risk psychosocial profile was created for each athlete through the use of The Sport Anxiety Scale (Smith et al. 1990b), the Life Event Scale for Collegiate Athletes (Petrie 1992), and the Athletic Coping Skills Inventory-28 (Smith et al.1995). They implemented an intervention scheme which taught athletes skills such as stress management and confidence building. Their study showed that these athletes were injured far less than athletes in a control group. Maddison and Prapavessis (2005) conducted a similar study with rugby players, and found that athletes in the intervention group (who were taught to manage stress) had fewer injuries than athletes in the control group. Such studies powerfully demonstrate how psychological interventions can be used to impact the injury process – something often thought of as purely physical!

Conclusion of the stress model

All the components of the stress model have been described and it should now be clear how an integration of these various components works. An athlete’s personality, their previous experiences and ways of dealing with excessive demands feeds into the way they respond to stress. Their stress response is affected by their thoughts, their focus and their bodily reactions. Intervention strategies such as goal setting, self-talk, coping strategies and imagery, which will be discussed in the second part of the chapter, can help reduce levels of stress caused by the stress response and reduction of stress levels can reduce the incidence of injury.

To strengthen your knowledge on the model and coping strategies, refer to: Williams and Andersen (1998) and Lazarus and Folkman (1984).

The next part of the chapter will continue with the emotional response to injury within the stage model (Kübler-Ross, 1969).

Emotional responses to sports injury and rehabilitation: A stage model

Being injured is obviously an emotional experience for your athlete (Heil 1993). Tracey (2003) examined the emotional responses experienced by athletes as a result of injury as well as during rehabilitation and revealed that athletes demonstrate a collection of emotions such as a sense of loss, decreased self-esteem, frustration and anger.

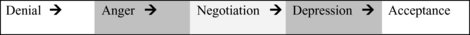

In examining athletic injury, a classic ‘stage’ model by Kübler-Ross (1969) has been applied to sport and outlines a normal progression of emotions (Figure 15.2). Originally, this model was designed as a framework for understanding the psychological response during the grieving process. However, it was adapted to parallel the stages of emotional response experienced by injured athletes (Crossman 1991). The initial stage is denial where athletes find it hard to believe that they are injured. This is usually immediately post-injury. Second is anger, which can be directed at the injury, oneself, or even you as medical staff. The third stage is one of bargaining where athletes negotiate a deal, for example, ‘I will do all my exercises and be a better person if I can fully recover and return to competition’. Next is a state of depression, followed by acceptance.

The Stages

Denial

There are two aspects of denial. Firstly, the shock state immediately following the injury when the player is in a state of disbelief and may even respond with shortness of breath and physical freezing. Secondly, it may progress into a denial period where the athlete still finds it hard to accept their limitations due to injury. You can respond back by going through the reality of the situation though it may take time for the athlete to accept it.

Anger

Secondly, the athlete may express their anger over the situation. They may enter a blame culture in feeling that others have put them here, thinking or saying things such as “The opponent should not have tripped me up …” Or they may suggest it is your fault for not doing a good enough job with a previous injury. The best way to manage anger is to stay calm, and never respond back with anger. Remember to defuse by allowing the athlete a bit of time to express their feelings and then to acknowledge that you understand that they are feeling angry and that this is quite normal. Can they remember a previous time when they felt angry due to an injury, illness or bad situation? How did they get through it then? What do they feel they could do to get through it this time?

Bargaining

This third stage involves negotiation. The athlete may promise to attend all sessions in exchange for your hard work as a rehabilitator in helping them to return to full recovery. This can include religion where an athlete will promise to be a better person in return for better health.

Depression

Depression is a sense of hopelessness and despair, and athletes may express sadness and apathy through statements such as “my sports career is over”. Your athlete may not feel like coming to rehabilitative sessions or working hard at the home exercises you have given them. When athletes feel despair you can try to boost their emotions by examining a positive focus. For example, what will you do when you complete your rehabilitation? How will you celebrate your return to sport? Can you remember or visualise a time when you felt really successful or happy in your sport?

Acceptance

Be encouraging and acceptance will be around the corner. Acceptance is acknowledging that an injury has occurred and that the way forward is by working through the rehabilitative process. Your athlete may demonstrate this by saying “I am going to the gym regularly and working on these exercises at home.”

Conclusions on the stage model of grief-loss

The Kübler–Ross (1969) stage model has been criticised for being sequential or outlining a set order for this emotional experience. However, psychologists agree that these stages are more like fluid phases and that not all athletes may go through all these emotions in the same order. Some athletes may even not display these emotions at all. So as a professional, just be aware of what emotions your client may be going through.

Carson and Polman (2008), in working with anterior cruciate ligament patients, identified set stages of shock, depression, relief, encouragement and confidence development. To further your knowledge of the Kübler-Ross grief loss model, read the article entitled ‘Psychological responses to injury in competitive sport: a critical review’ written by Walker, Thatcher and Lavallee (2007). They conducted a study to help professionals (such as you) who are involved in athletic rehabilitation to understand the impact of psychological factors on injury experience. Their research critically examines models such as grief-loss (e.g. that of Kübler-Ross) and explores the integration of emotional, behavioural and cognitive responses to injury and recovery and what they conclude is a rather complex model.

Behavioural responses to sports injury and rehabilitation

Adherence

Adherence is a type of ‘stickability’. For you as sports rehabilitator, it is about getting a patient to stick to a recovery programme which may include adherence to rehabilitation sessions, to a special diet, to home exercises, to attending adapted training programmes and to working on the development of mental strategies. Creating an individualised rehabilitative programme that includes psychological techniques will benefit your patient in facilitating recovery in the most efficient way possible.

Adherence differs from compliance, which assumes that the patient will obediently follow your instruction without question. Adherence is a voluntary, negotiated agreement between the patient and you. Patient involvement is important and is positively related with adherence (Lind et al. 2008). However, not all athletes will follow your rehabilitation programme as agreed, and adherence can range from under-adherence to over-adherence. Under-adherence is doing less than what is prescribed. The cost of under-adherence to the patient may be a slower recovery as well as lower confidence about their progress. Sometimes additional factors can interfere with progress and be the cause of under-adherence. For example, athletes may receive more attention from their coaches and team members when they are injured than when they are fit. They may also want to avoid the pain associated with having to following a regime of rehabilitative exercises. Remember that patients can forget to stick to their programmes once or twice, but forgetting three times is probably no longer an accident. Athletes need to display the same commitment to their rehabilitation as they do to their training, though it is important as sports rehabilitator to remember that today’s patients have to balance other commitments as well such as study, friends and family.

Over-adherence, on the other hand, is doing more than one should during recovery. Some athletes will over-adhere to a rehabilitation programme in the hope of recovering quicker. This may be due to not wanting to lose their place in an upcoming competition or a position on a team, perfectionist tendencies, or perhaps pressure from other people such as their coach or teammates.

One way of helping athletes to adhere to their recovery programme is to get them to use a diary. An interesting study by Pizzari, Taylor, McBurney and Feller (2005) examined the relationship between adherence and outcome following ACL surgery. Adherence was measured by a self-reported diary of home exercise and from attendance to appointments. In clinical practice, the use of a diary to track daily and weekly progress is an easy way of both empowering the athlete to track their own progress, and perhaps for you to examine adherence – if they let you see their diary, that is! Of course, willingness to keep a diary in the first place is one indicator that an athlete is keen to be proactive in the rehabilitation process. The results indicated that there was a relationship between adherence to home exercises and outcome, measured by knee function. Home exercise adherence is an important predictor of the rehabilitation adherence and was also demonstrated in a study of patients with wrist fractures (Lyngcoln et al. 2005). The use of a self-reported diary to track home exercise appears to be a useful way of monitoring adherence, you may wish to consider this when working with clients.

Factors that influence adherence

Through interviews with sports physiotherapists, Niven (2007) identified a number of factors that influence adherence in sports rehabilitation programmes. In particular and athlete’s personality as well as situational factors impact adherence to rehabilitation programmes. Personality may impact on adherence as athletes who are high in anxiety show reduced adherence to their rehabilitative programmes (Taylor and Taylor 1997). In addition, how your athlete perceives the efficacy of your treatment protocol and the confidence they have in rehabilitation will affect their adherence to your sports injury programme (Brewer et al. 2003; Taylor and May 1996).

To help your athlete to have confidence in you, effective communication and a solid working relationship are essential. In fact, when physiotherapists and athletes have these factors in place, a more effective recovery programme and more positive outcomes result (Crossman 1997; Francis et al., 2000; Ninedek and Kolt 2000).

Determinants of adherence

One way of altering adherence is to identify the factors that determine their adherence to a programme. Crossman (2001) divided the factors into three classifications: predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors.

Predisposing factors

These are the athlete’s own views and thoughts about the recovery process. In order to get an idea from your patient about their perceptions towards rehabilitation you may want to ask about their normal habits and preferences.

For example:

- Do you like working out in the gym or undertaking extra training?

- What do you like most about participating in your sport?

- How will training or home exercises help you to get closer to your goal?

- How are you going to make sure you can achieve your goal of returning fit?

Reinforcing factors

Reinforcing factors are based on the interactions between the athlete and the other significant others such as the sports rehabilitator, coach, the team or other important persons.

For instance, you could ask:

- Are you in touch with the coach and your team?

- Do you feel that there is a good reason to go through the recovery process?

- Has the rehabilitative process been explained to you?

Enabling factors

These are to do with the environment surrounding the rehabilitation treatment. Being able to identify which of these factors is preventing an athlete from attending sessions can help you as sports rehabilitator to improve your client’s adherence. For instance, you might ask about:

- Is it easy or hard for you to get to you appointments? What can be done to make attending easier?

- How do you get to these sessions?

- How long does it take you to get home afterwards?

- Are there things (e.g. homework, other appointments, family duties) that make it hard for you to complete your home exercises?

As a rehabilitator it is helpful to identify the predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors behind adherence in your athlete so that you can work on modifying any unhealthy behaviours or thoughts thus strengthening the rehabilitative process. For further reading please see: Crossman (1997), Francis et al. (2000) and Ninedek and Kolt (2000).

Mental toughness and rehabilitation

Mental toughness is having a psychological advantage in coping with the stressful demands (Fletcher and Fletcher 2005) associated with competition as well as in rehabilitation and return to sport after injury (Jones et al. 2002). Although mental toughness is a relatively new area of research, studies are demonstrating that these factors are important as part of an athlete’s mindset. Levy, Polman Clough, Marchant and Earle (2006) found that patients with high mental toughness were more capable of managing pain and displaying a more positive outlook.

Mental toughness is defined by Middleton, Marsh, Martin, Richards and Perry (1997) as “an unshakeable perseverance and conviction towards some goal despite pressure or adversity”. Jones, Hanton and Connaughton (2002) state that it is, “the natural or developed psychological edge that enables you to generally cope better than your opponents with the many demands that sport places on a performer” So mental toughness is about being able to cope under pressure and not giving into it.

So does mental toughness help in a rehabilitative setting? Mentally tough individuals have been shown to demonstrate a greater ability to withstand physical pain (Jones et al. 2002) and to recover more quickly from injury (Gucciardi et al 2008). In addition, mentally tough participants perceive their injury to be less severe, feel that they are less susceptible to further injury and focus less on their pain during the course of their rehabilitation (Levy et al. 2006). Perhaps surprisingly, even greater attendance at rehabilitation sessions is demonstrated by those with greater mental toughness (Levy et al. 2005; Marchant and Earle 2006). If you want to explore this area further begin by reading the following: Gucciardi et al. (2008), Jones et al. (2002) and Levy et al. 2006.

Implications of emotional and behavioural responses

In summarising section one of this chapter you can see how there are several implications for you as a sports rehabilitator in understanding and incorporating psychological theory into your practice. To start with, you need to be aware of the relationship between stress and injury because you are in a key position to identify and help athletes who are at a greater risk of injury. As a sports rehabilitator it is useful to understand how personality affects the stress process and how an athlete’s past can affect how they deal with a stressful situation. As a sports rehabilitator, you are in a good position to encourage athletes to improve their coping strategies in handling stressful major life events as well as in handling daily hassles (Johnson et al. 2005). By catering to the emotional and behavioural needs of your athlete you are more likely to offer a comprehensive treatment that will enable your athlete to be stronger both psychologically and physiologically. Recovery can also be optimised through adherence and mental toughness.

Finally, Tracey (2003) points out that the experience of injury can give an athlete an increased understanding that recovery is a process in which an athlete can reflect and grow emotionally. You, as a rehabilitator, are often in a unique position to become involved in developing intervention programmes for athletes. There have been a variety of psychological interventions identified which facilitate adjustment to injury, such as goal setting, imagery and stress management (Evans et al. 2000; Johnson 2000; Johnson et al. 2005). Interventions in terms of psychological skills training and how they can be used will now be explained.

Psychological skills training in the injury process

The injury process may be simplistically divided into the time before an injury (pre-injury period), and the time following injury, lasting until the performer is fully rehabilitated and ready to return to activity (rehabilitation period). The role of psychological skills training (PST) in each stage will be outlined in this section. It is important to recognise that while the physical therapist or sports rehabilitator is not a sport psychologist, they are still in a good place to encourage injured athletes to practice mentally, and to give them some basic tips about how to do so (Gordon et al. 1998). This part of the chapter informs you about what psychological skills are, and how they may help prevent injury as well as support injury rehabilitation. You will notice that imagery is mentioned more frequently than other psychological skills; this is only because there is more research into its role and effectiveness. But, one study found that of a number of psychological skills, people actually rate goal setting as their favourite (Brewer et al. 1994). This means that it might be easier to “sell” goal setting to the people you meet; perhaps because it feels like a very practical and not overly ‘psychological’ technique. Still, the best approach is probably to recommend a variety of psychological skills to injured performers, so that they can choose what suits them best. If you are interested in exploring this topic further, a chapter by Kolt (2000) gives a very interesting example of how physical and psychological treatment following ACL reconstruction can go hand in hand. For additional material, see the books on the psychological aspects of injury by Pargman (2007), Taylor and Taylor (1997), and Heil (1993).

Psychological skills and psychological skills training

Psychological skills (sometimes called mental skills) include goal setting, imagery, self-talk and various forms of relaxation, and PST (or mental skills training, MST) is simply the systematic training of such skills. For example, a hockey coach who does a bit of informal goal setting with his team in order to prepare for the upcoming season would be said to use the psychological skill of goal setting. If, instead, he designs and implements a programme of goal setting over a number of weeks, perhaps teaching his athletes about how to make goal setting effective and evaluating it at the end, he could be said to be implementing a PST programme. As you might imagine, the effects of the various psychological skills are greater when implemented systematically; therefore, it is a good idea to learn more about, and regularly practice, these skills. You might also be wondering which psychological skill is ‘best’, or whether you have to study and practise (or recommend) them all. But while that might seem a simple and straightforward question, the answer is that there is no known ‘optimal recipe’ for how to use PST. Some researchers examine only one skill, and some examine several; however, because of the enormous number of sports, age groups, study purposes, and potential combinations of psychological skills available, there is no easy way in which to answer the question of which psychological skills to practice. But do not worry, sport psychologists often recommend a number of different skills, or combinations of skills, to performers. This way, the performer can choose what works best for them and their particular circumstances, and the chances of success are optimised. The individual psychological skills will now be introduced in turn.

Goal setting

Goal setting is a process of planning ahead for what one wants, and how to get there. This means that there is a huge variety of potential goals both for “normal”, healthy sports participation and for rehabilitation. For instance, for one athlete, a rehabilitation goal might be to be back on form by the last game of the season, while others take a more process-oriented approach and set themselves the goal of doing their rehabilitation exercises three times daily. Even if you haven’t studied much goal setting, you may still have heard a common acronym for how goal setting is made effective; this is the SMART acronym, which indicates that goals should be specific, measurable, accurate, realistic, and timed (Cox 2001; Weinberg and Gould 2007). It is important that most goals set are focused on individual performance (e.g. re-gaining complete strength of an injured leg) and the processes that contribute to this (e.g. doing three sets of eight reps of the rehabilitation exercises daily for three weeks). Such process and performance goals are superior to setting mainly outcome goals (e.g. returning faster from injury than another injured player, so that you will be the one to make the team; Filby, Maynard and Graydon 1999). This is so because outcome goals depend to some extent on factors outside your control, and may contribute to lowered self-confidence and heightened anxiety. Individually appropriate and relevant goals set jointly between the performer and their rehabilitator and, where appropriate, a coach, will instead promote a sense of control (Taylor and Taylor 1997). In rehabilitation, goal setting is one of the favourite methods for athletes to ‘get back on track’ (Brewer et al. 1994; Durso Cupal 1998).

Imagery

Imagery is the creation, or re-creation, of experiences in your mind (White and Hardy 1998). It may involve one or more senses, such as seeing yourself perform a particular exercise, feeling muscles move, and so on. Most imagery work in sport focuses on fairly concrete imagery to do with oneself (e.g. a gymnast imaging herself completing a floor routine), but more abstract, metaphorical images have also been reported, especially in the literature on healing imagery (Korn 1983; Ievleva and Orlick 1991; Green 1992; Evans et al. 2006) and in artistic activities like dance (Hanrahan and Vergeer 2000; Nordin and Cumming 2005). In metaphorical imagery, a performer might imagine the hip joint moving as a wheel or imagine toxins as a black substance that are gradually rinsed out or diluted with the breath – in other words, actions that are not strictly accurate but that may support a person’s understanding of a movement, induce relaxation, or similar. The types of imagery that performers may use during rehabilitation include all those experienced in their everyday lives (including seeing and feeling how they perform certain skills so that they don’t forget how to do them while ‘out’ with an injury). However, performers have also been found to engage in healing-type images when injured (Driediger et al. 2006; Evans et al. 2006; Green 1992; Hanrahan and Vergeer 2000; Ievleva and Orlick 1991; Korn 1983; Milne et al. 2005; Nordin and Cumming 2005; Sordoni et al. 2000, 2002; Short et al. 2004). Healing imagery might include metaphorical images such as those described above, but also more concrete images of physiological processes related to healing, such as tissue repairing itself back to normal. While healing imagery appears to have positive results, be mindful that people sometimes have strong preferences when it comes to imagery types. For example, some people respond really well to images of white blood cells eating local irritants and of cleansing, white air entering the lungs and circulation. For others, such abstract imagery might feel far-fetched or airy-fairy. Some performers value in-depth imagery of anatomical structures and how they function; for others that might be too complex. Thus, be creative in your use and encouragement of imagery, regularly checking that you and the client are ‘on the same page’. Offering a menu of images, ranging from strictly anatomical to very abstract, might be a good idea, as is having examples and anecdotes of how such images have been helpful to other clients at the ready.

For those who work with injured performers (e.g. physiotherapists, sports physicians, sports rehabilitators) to encourage their clients to use imagery effectively, they must clearly first learn about how imagery can be used to assist injured athletes (Driediger et al. 2006). In addition, having tried it out yourself first is essential. One useful approach is for the rehabilitator to link imagery in relation to injury with the imagery that an athlete likely already does as part of their training. For example, you could ask them to describe how they rehearse sport skills, strategies, and scenarios in their mind around competition, and then say that imagery in the rehabilitation process is really similar. This should help reassure the athlete that they already have the requisite skills to do rehabilitation imagery. If you inform them that healing imagery has been shown to be effective in well-controlled research studies, it might also help dispel some of the uncertainty or apprehension about a form of imagery that is perhaps less intuitive than simple mental rehearsal (Morris et al. 2005; Wiese et al. 1991).

Self-talk

The cognitive process of talking to oneself is simply referred to as self-talk. Like imagery, it is a basic form of thought and most of us do it all the time – although more or less consciously. Self-talk may be positive, negative, or neutral in nature (Hardy et al. 2001. 2005), and although some athletes report that negative self-talk is motivating for them (Van Raalte et al. 1995; Hardy et al. 2001), mostly the research findings are as you might guess; that is, more positive results come from positive self-talk, and more negative results come from negative self-talk (see Hardy (2006) for a more in-depth discussion). Positive self-talk includes generally motivating statements like “I know I can do this!”, whilst negative self-talk might include statements such as “she gave me just too many rehabilitation exercises – I will never be able to do them all every day”. Neutral self-talk may be instructional in nature, including statements such as “arm in line with body, shoulders relaxed”, perhaps designed to help remember and execute a shoulder rehabilitation exercise correctly.

Relaxation

Whilst a number of PST ‘packages’ include relaxation, it is rarely investigated on its own in sport psychology; thus, the number of studies examining the effects of relaxation for injured performers are few and far between. Even so, relaxation is a widely used technique that appeals to many performers, as most people intuitively appreciate the feeling of being calm and relaxed. A number of ways of achieving a relaxation response exist, and we will not describe them all here; instead, we will limit ourselves to a brief outline of some methods that are typically employed in PST programmes. Note also that while the sport psychology literature typically refers to relaxation ‘techniques’ or ‘procedures’, many people have developed their own ways of relaxing; for instance just by breathing deeply, by listening to music, or by doing yoga or another form of calming exercise.

One of the best known of the established techniques is progressive relaxation, first proposed by Jacobson in 1929. In this technique, the performer first contracts a particular muscle group, and thereafter relaxes it. This way, it is proposed that the athlete will learn to distinguish between the feelings of tension and relaxation. It is notable that imagery seems to play a part in progressive relaxation; that is, a typical progressive relaxation script would guide the participant’s attention toward the feeling of their muscles relaxing, in a suggestive fashion. For example, a script used by Gill, Kolt, and Keating (2004, p292) tells participants to “Relax your feet and lower legs. Be aware of the tension being released. Release all the tension. As the tension fades away, focus on the new relaxed feeling in your feet and lower legs. Continue to focus on this feeling.” Another form of relaxation is autogenic training, created by psychiatrist Johannes Schultz in 1932. It is somewhat similar to progressive relaxation, with both techniques going through various parts of the body and involving imagery as well as suggestive statements concerning the body being relaxed. Different from progressive relaxation, however, autogenic training focuses on limbs being warm and heavy, and typically also focuses more on the regulation of heart rate, breathing, and temperature (Cox 2002; Noh and Morris 2004).

Combined PST

As noted above, many studies as well as real-life interventions use psychological skills in combination. The following examples give you some idea of how that might be done:

- use self-talk to guide yourself through an imagery sequence

- imagine yourself achieving a goal

- setting a goal to do imagery for 10 minutes daily in order to enhance performance

- use self-talk to remind yourself of your goals

- and if you have learnt a relaxation procedure, simply thinking through that procedure would be a form of self-talk, as you would be telling yourself what to do!

Coping skills

Some researchers into PST and injury have looked at the concept of coping skills. Indeed, coping resources are a key component of the Williams and Andersen (1998) model of stress and athletic injury described above. Somewhat similar to psychological skills, coping skills typically include goal setting and/or another form of mental preparation, but also deals with constructs such as coping with adversity, peaking under pressure, concentration, freedom from worry, confidence, achievement motivation, and coachability (Smith et al. 1995). In other words, having good coping skills means that a athlete would handle a variety of situations in a confident, capable way and be resilient to setbacks. Note that while these coping skills should help a performer cope with varying circumstances, the psychological skills literature would typically argue that characteristics such as concentration, self-confidence, and freedom from worry and excessive anxiety, and may be achieved through PST. For example, goal setting might be used to improve a footballer’s anxiety levels, or imagery might be employed for a runner who would like to improve her self-confidence. So what does all this mean for you in practice? Well, simply that it is important to be clear about what it is you want to achieve (e.g. being able to cope with adversity, such as returning from a debilitating, long-term injury), and the techniques that might be available to help you do so (e.g. the psychological skills of goal setting, imagery, self-talk and relaxation).

Psychological skills training in the pre-injury period

One of the most fascinating findings that have emerged in recent years is that psychological skills training can help performers avoid injury. The findings related to injury prevention fall into two categories: reduced injury frequency, and reduced injury duration.

Reduced injury frequency

The existing research indicates that a multitude of positive benefits stand to be obtained from PST, including preventing injuries from happening in the first place (Davis 1991; Johnson et al. 2005; Kerr and Goss 1996; Kolt et al. 2004; May and Brown 1989; Perna et al. 2003; Schomer 1990). In one study, a relaxation and imagery intervention reduced injury by as much as 52% (Davis 1991). Intervention studies have used various combinations of psychological skills and stress inoculation training (essentially training performers to handle stress better over time) to reduce injury frequency. And although this means that we do not have a very clear idea of which psychological skill does what, it also suggests that the effect is fairly robust. Moreover, the activities used in the various studies have included soccer (Johnson et al. 2005), alpine skiing (May and Brown 1989), swimming (Davis 1991), gymnastics (Kerr and Goss 1996; Kolt et al. 2004), rowing (Perna et al. 2003) and marathon running (Schomer 1990); this diversity further suggests that the findings are not anomalous, unique or sport-specific. Instead, the studies indicate that the effect is due to PST helping athletes lower their stress levels, feel more confident and optimistic, becoming more aware of their bodies, and building their ability to cope with difficulties.

Reduced injury duration

In a study by Noh, Morris, and Andersen (2005), it was shown that ballet dancers’ psychological skills and coping strategies distinguished between not just those with higher versus lower injury frequencies, but also between dancers with shorter and longer injury durations. Specifically, dancers with shorter injury duration reported less worry and negative stress. They also had greater levels of confidence and achievement motivation. These authors later used their findings to conduct an intervention study, again with ballet dancers (Noh et al. 2007). After teaching one group imagery, self-talk and autogenic training (a form of relaxation), the group improved not only their coping skills, but also spent less time injured than a control group. Another study in rugby yielded similar findings (Maddison and Prapavessis 2005). In their study, rugby players considered to have an “at-risk psychological profile for injury” were identified and undertook a stress management programme. Like the ballet dancers in Noh et al.’s (2007) study, these rugby players gained better coping skills, worried less and spent less time injured than a control group.

Sample PST programme to prevent injury

1. Set goals regularly. Make sure they are SMART in nature, and focus more on yourself and your own progress than on how you compare to others. Get regular feedback from knowledgeable people (e.g. coaches) on your progress, and use this as well as your own judgment to keep goals flexible, and to evaluate progress. A training diary is a useful tool to help you keep track of goals and progress.

2. Use imagery daily. Explore imagery in all its forms – play around with different types and use it for a range of purposes – improving performance and confidence, reducing stress, and focusing you on your goals. For example, you can imagine yourself performing technical skills in detail, rehearse strategies for how to get out of potential ‘trouble’ (e.g. being a player down), imagine each component of a game the night before to ensure that you are prepared, see yourself reaching your overall goal, or use metaphorical images to enhance the quality of your performance. Make your images multisensory, because this makes them more effective; so, see yourself playing your sport, and feel your muscles move efficiently and the emotions you want to feel. You may even want to hear the sounds, and smell the venue! Regular, deliberate imagery will soon reap benefits for the activity – and the injury prevention will come as a nice bonus.

3. Use self-talk to your advantage. Make sure that your inner chatter is beneficial to your performance as well as to your well-being. Having positive self-talk statements ‘ready-made’ is one of the best ways of banishing negative statements if and when they surface; focus your attention on your positive statement, and repeat it over and over if necessary. With time, you will identify negative self-talk quickly and get rid of it just as quickly. In addition, you can use instructional self-talk to focus your attention on the task at hand; for example, a tired runner might feel her mind wander, thereby risking injury due to not focusing on the terrain underfoot. By repeating instructional statements to herself (e.g. feedback from her coach such as ‘shoulders loose, arms swinging freely’ or metaphors such as ‘light as a cheetah’), she keeps her attention in the here-and-now.

4. Relax – you deserve it! Many people, and athletes are no exception, experience unwanted stress and tension in their everyday lives. The relaxation strategies described above can be good ways of eliminating some of this tension, as well as providing a pleasant difference for your muscles from their hard work on the court, pitch, dance floor, or ring. You might also want to use relaxation to improve your body awareness – for instance, what parts of your body typically tense up? Why might that be? Is there something you need to change in your exercise, sport, or everyday habits to improve it? It seems likely that being able to relax helps prevent injury through removing excess tension, stress and anxiety, and perhaps through improved body awareness.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree