Prolapse

Introduction

Introduction

Symptoms caused by prolapse of the female pelvic organs are a common health problem. Up to 28% of parous women under 45 are affected by prolapse [Rinehart et al. 1984]. The conditions become manifest in many different symptoms, which may occur alone or in combination. Referrals by physicians to physical therapists relate primarily to pregnancy, to delivery, or to disorders of the storage and voiding functions of the bladder and/or rectum. Although an evidence-based protocol for the physiotherapeutic treatment of prolapse is not currently available, incipient prolapse can be treated effectively with physiotherapy.

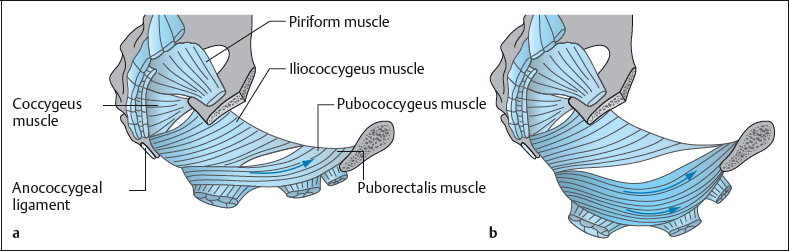

Since the levator ani muscle provides the main support for the pelvic organs, rehabilitation of the pelvic floor plays a central role in the treatment of genital prolapse in women [Norton 1994]. Some of the therapeutic procedures for treating and preventing female prolapse described below are in part drawn from the field of pelvic floor reeducation.

Genital prolapse is defined as the descent of one or more pelvic organs into or through the vagina [Stanton 1992].

Genital prolapse is defined as the descent of one or more pelvic organs into or through the vagina [Stanton 1992].

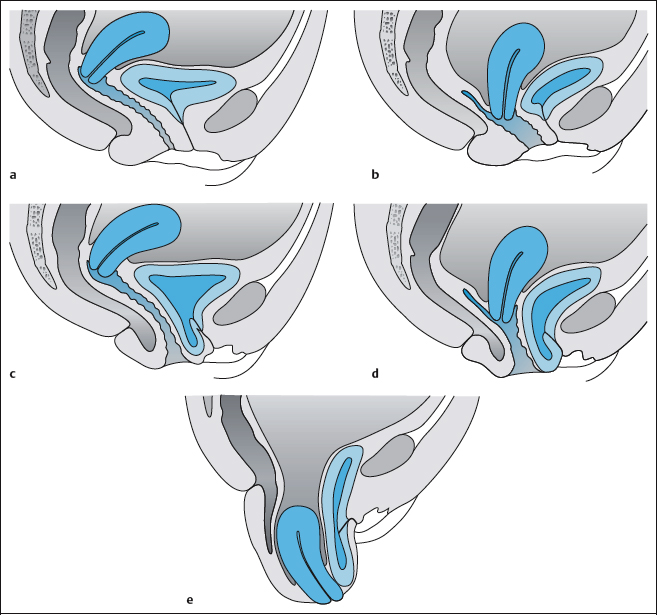

The main feature of the condition is a descent of the vaginal walls and/or the uterus. The vaginal wall normally has a certain degree of pliability, but what is decisive is the degree of the descent [Stanton 1992]. In prolapse, the physiological degree of plasticity in movements of the female pelvic organs is clearly exceeded, and the organs descend more deeply than normal. This condition can be transient (e.g., postpartum) or permanent, static, or progressive. Genital prolapse includes cystocele (descent of the vaginal mucosa covering the bladder), urethrocele (descent of the vaginal mucosa covering the urethra), and rectocele (descent of the vaginal mucosa covering the rectum). The uterus (uterine prolapse) and the vault of the vagina (prolapse of the vaginal vault) may also descend.

Terminology

Terminology

In an effort to standardize prolapse terminology, the International Continence Society (ICS) attempted in the 1990s to substitute the term “segments of the lower genital tract” for current terms such as cystocele, rectocele, etc. [Bump et al. 1996]. In more recent terminology [Viereck et al. 1997], the individual potentially prolapsing compartments include:

- Anterior vaginal wall

- Uterus

- Vaginal vault

- Posterior vaginal wall

Descent of the vaginal wall can occur with or without involvement of the adjacent pelvic organs; the bladder, urethra, uterus, vaginal stump, small intestine, and rectum may be involved in a prolapse, either alone or in various combinations.

Classification

Classification

Descent is generally classified by the anatomic structure involved and by the severity (Table 4.17). Not all authors use the terms in the same way: “descent” and “prolapse” are also used synonymously, rather than as indicators of severity. Partial descent though the introitus is termed “subprolapse”; complete inversion is “total prolapse” or “procidentia” (Figs. 4.38, 4.39).

Since 1993, an international multidisciplinary work group—including members of the International Continence Society (ICS), the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS), and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS)—developed criteria for fema e genital prolapse and introduced metric quantification of the condition. The new ICS Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification (POPQ) system is based on nine points and is currently the gold standard for prolapse diagnosis [Schüssler 2000]. The protocol involves assessment of a number of individual items, consisting of the hymen as a fixed reference point and six precisely defined points relative to it: two in the anterior vaginal wall, two in the posterior vaginal wall, and two in the apex. Three more measuring points complete the quantification system: the length of the genital hiatus and the perineal body, and the total length of the vagina [Viereck et al. 1997]. These last three measurements alsoprovide information about the descent of the pelvic floor.

| Prolapse | Grading |

|---|---|

| Cystocele | I–IV |

| Urethrocele | I–III |

| Cystourethrocele | |

| Uterine prolapse | I–IV |

| Rectocele | – |

| Enterocele | I–III |

| Prolapse of vaginal vault |

This protocol classifies prolapse into ICS grades 0–IV. The hymen serves as a precise, visually recognizable reference point [Viereck et al. 1997], to which the change in position of six precisely defined vaginal points can be referred (Table 4.18).

This protocol classifies prolapse into ICS grades 0–IV. The hymen serves as a precise, visually recognizable reference point [Viereck et al. 1997], to which the change in position of six precisely defined vaginal points can be referred (Table 4.18).quested to strain down vigorously in the recumbent position and if applicable also in the standing position. The vaginal folds should become tense and be obliterated. Pulling on the prolapsed tissue manually determines whether it will descend further. The patient confirms by her sensations, or with a hand-held mirror, that the visible prolapse corresponds to the fullest extent of the prolapse she experiences in her everyday life [Bump et al. 1996].

In an examination of 274 patients with genital prolapse or urinary incontinence, a close relationship was demonstrated between hypermobility of the urethra (determined using the Q-Tip test) and prolapse of grades II, III, and IV from point Aa. In the ICS quantification system, with intact topography point Aa lies 3 cm proximal to the external urethral meatus, in the midline of the anterior vaginal wall. Urethral hypermobility was present in 95 % of patients who had a grade II prolapse of point Aa and in 100 % of those who had prolapse of grades III and IV [Cogan et al. 2002].

| Grade | Finding |

|---|---|

| 0 | Normal anatomy; all six points are proximal to the hymen to the fullest extent |

| I | The most distal point of the prolapse is more than 1 cm proximal to the hymen |

| II | The most distal point of the prolapse is 1 cm or less proximal or distal to the hymen |

| III | The most distal point of the prolapse is more than 1 cm outside the hymen |

| IV | Complete procidentia/eversion of the total length of the lower genital tract |

Descending Perineum Syndrome

Descending Perineum Syndrome

Parks et al. first described this phenomenon of the descent of the pelvic floor in 1966 [Benson 1992] (Fig. 4.40). The specific marker for this type of prolapse is that the perineum partly descends past the plane of the two ischial tuberosities even at rest, and massively during straining. The impressive external ballooning of the perineum exceeds 2cm, and in Markwell’s clinical experience it can exceed the resting position by 5–12cm during straining [Markwell 2001].

This is accompanied by chronic denervation and reinnervation of the levator ani and the sphincter muscles, with overdistension of the fascia of the pelvic floor. The abnormal descent of the perineum leads to changes in the striated anal sphincter, because its nerve supply is damaged. In the descending perineum syndrome, the tissue is stretched by at least 2cm during straining, and this stretches the relevant nerves by 20% of their anatomic length, potentially causing irreversible damage. This syndrome can be accompanied by enterocele, rectocele, or rectal prolapse; fecal incontinence may also develop. Henry et al. [1982] examined the pelvic floor musculature of patients with descending perineum syndrome and found that half of those affected were incontinent of feces. The etiology of the descent of the pelvic floor was attributed to vaginal delivery and years of chronic straining at stool.

Dynamic Imaging

Dynamic Imaging

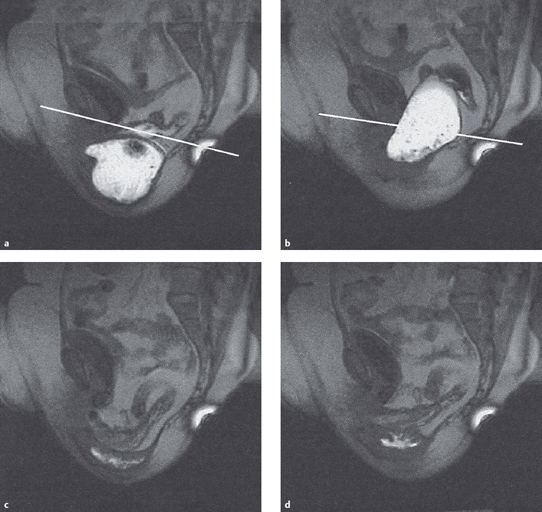

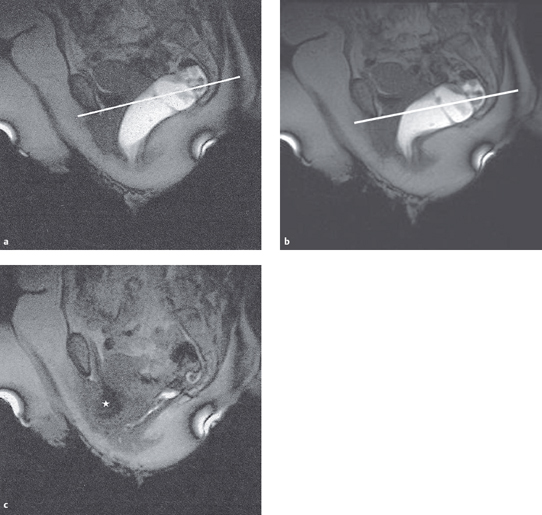

The optimal imaging procedure to examine the descending perineum syndrome is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figs. 4.41, 4.42). This has replaced conventional radiographic methods of displaying the anterior, middle, and posterior compartments of the pelvic floor. MRI is particularly suitable for displaying enteroceles, the extent of which is often underestimated. The availability of rapid sequences makes it possible to carry out a dynamic examination of the various functional states of the pelvic floor. The whole pelvic floor can be displayed comprehensively at rest, during abdominal straining, during maximal contraction of the pelvic floor muscles, and during defecation. A line joining the lower border of the symphysis and the lowest coccygeal joint serves as a reference plane for the bladder, vagina and rectum, to determine the degree of pelvic floor descent (Fig. 4.41). For this purpose, descent is divided into three stages: mild, moderate, and severe [Roos et al. 2002]. In 1998, the MRI center at the university hospital in Zurich installed an open MRI system that allows dynamic examination of the patient in a functional sitting position [Weishaupt 2002].

Causes of Prolapse

Causes of Prolapse

The pelvic floor consists of layers of muscle and fibrous tissue, forming the lower boundary of the abdominopelvic cavity. The pelvic organs are supported in part by the striated muscles of the pelvic floor and in part by its fibromuscular components. Prolapse results when the integrity of the pelvic floor is compromised because these supportive layers become inadequate. Pregnancy, vaginal delivery, and the process of aging are known to lead to damage to the pelvic floor, which contributes to the development of prolapse then or later in life. It is not always possible to determine unequivocally which part of the pelvic floor is playing the dominant role when prolapse symptoms develop. Apart from the muscular and nervous components of the pelvic support mechanism, fibrous tissue structures may also contribute to the development of prolapse [Nichols and Randall 1996].

The Effect of Birth

The Effect of Birth

Vaginal birth is recognized as a major cause of prolapse (Fig. 4.43) [Warrell 1992]. At least 50 % of parous women develop a descent in the course of their lives, although only 10–20% seek medical help [Schulz 2001]. Delivery can lead to anatomical defects in the anchoring of the vaginal wall to the tendinous arch of the pelvic fascia, and the vaginal wall can descend as a result. Due to overstretching of fibrous tissue, delivery can also result in tears in the fibrous tissue, leading to scar formation [Norton 1992]. Even before this, pregnancy itself can contribute to the development of prolapse due to hormonally based tissue changes [Nichols and Randall 1996]. Stretching of the pudendal nerve during delivery can also lead to neurogenic damage to the pelvic floor.

Neurophysiologic studies show that in prolapse, the pelvic floor is partially denervated. In comparison with asymptomatic women, women with genital prolapse or stress urinary incontinence show an increase in denervation of the pelvic floor and sphincter muscles [Warrell 1992]. Smith et al. [1989], using electrophysiological measurements and histochemical examination in women with prolapse or stress urinary incontinence, found that with increasing age the density of the fibers in the motor unit increased and the nerve conduction velocity decreased in the nerves to the pelvic floor and urethral sphincter.

The Effect of Aging

The Effect of Aging

Dimpfl et al. [1998], while studying changes in the muscular tissue of the pelvic floor, investigated an interesting aspect of pelvic floor symptomatology. They described muscular changes in the levator ani that are caused by both vaginal birth and the aging process, and which are histomorphologically indistinguishable from each other. According to this study, these changes are more marked in the anterior, paraurethral parts of the musculature of the pelvic floor. The study was unable to confirm the findings of other studies, showing evidence of neurogenic damage in the muscles of the pelvic floor. Dimpfl et al. [1998] mention the study by Heit et al. [1996], who, while studying genital descent, were unable to demonstrate the typical histomorphologic signs of denervation and subsequent reinnervation of the muscular components of the pelvic floor innervated by direct efferents from sacral roots S2 and S3.

Effect of Chronic Strain

Effect of Chronic Strain

In the presence of increased intra-abdominal pressure such as chronic cough and heavy physical labor the muscular and fascial supporting structures of the pelvic floor are exposed to constant stress and may be permanently damaged.

A commonly underestimated cause of prolapse is chronic strain during defecation. Sapsford [1998] mentions that chronic straining during defecation often precedes the development of prolapse. In a group of women with uterine prolapse, 61% had a history of chronic straining during defecation, while in the control group only 4 % of women had such a history. At the time of the examination, 95% of women with prolapse were constipated [Spence-Jones et al. 1994]. Years of excessive straining at stool can stretch the pudendal nerve, causing irreversible damage to the nerve. Nerves sustain irreversible damage even with a stretch of just 12% beyond their anatomical length. In women with perineal descent, the pelvic floor moves down by 2–3 cm, corresponding to a stretch of 20–30%. The resulting relaxation of the puborectalis and the external anal sphincter can eventually lead to the development of rectal prolapse and fecal incontinence [Kenneth et al. 1992].

Effect of Congenital Connective-Tissue Weakness

Effect of Congenital Connective-Tissue Weakness

The pelvic floor is subject to constant pressure due to the upright gait in humans. This pressure increases briefly during the imposition of extra strain such as coughing or the lifting of heavy loads. In the presence of congenital connective-tissue weakness, the support system cannot support this daily downward pressure, and a genital prolapse may ensue. In the USA, 2% of women with genital prolapse had no history of prior delivery [Nichols and Randall 1996]. Sayer and Smith [1994] were able to demonstrate collagen changes in women with prolapse, in comparison with those without prolapse. Women with uterine prolapse had a weaker and less distensible fascia. A weak pelvic fascia may reinforce damage to the muscles. For this reason, women with known congenital connective-tissue weakness should be offered preventive pelvic floor training [Sayer and Smith 1994]. Richter [1985] made a distinction between primary descent due to a weakened endopelvic fascia and secondary descent due to weakness of the pelvic floor muscles. Primary descent is marked by well-developed levator sides [Richter 1985]. This observation is in accordance with the clinical observation that when muscle function is tested, some women with uterovaginal descent can have an astonishingly strong and well-coordinated pelvic musculature.

Symptoms of Genital Prolapse

Symptoms of Genital Prolapse

The symptoms described by patients vary, depending on the location and grade of the descent. The symptoms may be local, or may become manifest through disturbances in the functioning of the adjoining organs. Incontinence of urine or feces is often the decisive symptom in prolapse that leads women to seek conservative treatment. Perineal descent and stress urinary incontinence are clinical conditions that are entirely independent of each other, but often exist side by side [Shull et al. 1999] and have overlapping treatments. Urethrocystocele is often the clinical correlate of stress incontinence.

Local Symptoms

Local Symptoms

In a uterine descent, patients describe a sensation of something coming down through or falling out of the vagina. They describe a sensation of pressure or heaviness, and/or the sensation of a poorly applied menstrual tampon. If the prolapse is marked, the prolapsed tissue may be painfully irritated while the patient is sitting or cycling, or even when there is friction caused by contact with clothing. If the prolapse passes through the levator hiatus, contraction of the muscles of the pelvic floor can cause painful incarceration of the prolapsed structure. Pain causes inhibition of the pelvic floor muscles, and this may lead to wasting of these muscles. Vaginal gas (also known as flatus vaginalis) is a very disturbing symptom of prolapse. It may supervene immediately after birth, or later. In this condition, the weakened pelvic floor allows air to be sucked into the dilated proximal vagina, and with changes of posture this can escape in an uncontrolled and noisy way [Markwell and Sapsford 1998].

Classification into Four Groups of Symptoms

Classification into Four Groups of Symptoms

For an overview of genital prolapse, it is helpful to divide the symptoms into four groups, as suggested by Bump et al. [1996] in the ICS classification protocol (Table 4.19).

| Urinary symptoms |

| Intestinal symptoms |

| Sexual symptoms |

| Other local symptoms |

Urinary Symptoms

- Stress urinary incontinence

- Frequency (pollakiuria) and nocturia

- Complaints of urgency

- Delayed micturition (hesitancy)

- Weak or prolonged urinary flow

- A sensation of incomplete emptying of the bladder

- The need to replace the prolapse by hand or even to assume a different posture in order to initiate emptying of the bladder or to empty it completely.

Rectal/Anal Symptoms

- Incontinence of flatus

- Incontinence of liquid or solid feces

- Stool staining

- Complaints of urge to defecate

- Pain with or after defecation

- Digital assistance through the anus, perineum, or vagina to achieve complete emptying of feces

- Sensation of incomplete emptying of feces

- Protrusion of rectal tissue during or after defecation

Sexual Symptoms

These are assessed by questions about sexual activity, sexual passivity and its causes, dyspareunia, incontinence during sexual activity, sexual frequency and enjoyment, and changes in the experience of orgasm.

Other Local Symptoms

- Sensation of pressure and heaviness in the vagina

- Pain in the vagina or the perineum

- The sensation that tissue is emerging from mthe vagina

- Feeling or becoming aware of unusual tissue masses

- Low back pain

- Abdominal pressure or pain

Low back pain is often described as a symptom of prolapse. Heit et al. [2002] published a study concluding that descent of the pelvic organs is not a cause of low back pain. They recommend looking for other causes of the pain before attributing it to prolapse.

Low back pain is often described as a symptom of prolapse. Heit et al. [2002] published a study concluding that descent of the pelvic organs is not a cause of low back pain. They recommend looking for other causes of the pain before attributing it to prolapse.

Symptoms of Descending Perineum Syndrome

The primary symptom is a marked difficulty to defecate normally, with resulting chronic prolonged straining. There is also a suggestion that prolapsing rectal mucosa causes a feeling of fullness in the rectum, which in turn induces straining. Pain can be a highly problematic component of the syndrome. It is a poorly localized form of deep discomfort precipitated by prolonged standing and relieved by lying down or sleep.

Basic Principles of Physiotherapeutic Procedures

Basic Principles of Physiotherapeutic Procedures

Basic Principles

Basic Principles

The musculature of the pelvic floor helps support the pelvic organs and contributes to their dynamics. It consists of skeletal muscles innervated by somatic motor nerves; it can be contracted voluntarily, and can therefore be trained. Training of these muscles follows the principles of rehabilitative training [Radlinger et al. 1998b]. Since the muscles of the pelvic floor are concealed, they cannot be checked visually. Training and integration of functional movement sequences is therefore only possible when adequate sensory information is received and integrated [Radlinger et al. 1998b]—i. e. through intact perception. If perception is deficient, an important first step in treatment is to provide instruction in how to perceive sensations from the pelvicfloor, enabling the patient to perceive her own body.

Development

Development

In the late 1940s, Kegel [1948] was the first to apply the exercise principles that were used for skeletal muscles at that time to the perineal muscles. He developed training recommendations that were based on visual feedback from a perineometer. Among other recommendations, he suggested that in women of childbearing age incipient cystoceles and rectoceles could improve by “restoring tone and function to the muscles of the pelvic floor” [Kegel 1948]. In addition to the pelvic floor exercises (Kegel exercises) that have traditionally been practiced since that time, therapeutic procedures for weakness of the muscles of the pelvic floor have also been developed and expanded in recent years. These have benefited from the discoveries and information in the field of pelvic floor reeducation described by Schüssler et al. [1994]. An independent, scientifically developed protocol for the treatment of prolapse has not yet been established as it has been for incontinence. In terms of the objective results of therapy, prolapse is apparently not as attractive a condition to treat if it is not accompanied by impairment of bladder and/or intestinal function. As Norton [1994] argued, this is why many patients present for therapy only when the prolapse has already progressed to the point at which the tissue lies below the plane of the levator ani. Given the close anatomic relationship between the lower urinary tract and the female genital tract, incontinence is a common symptom of prolapse, and the therapeutic procedures for the two conditions overlap. In a Norwegian study, 38% of women presenting with urinary incontinence to a general practitioner had genital prolapse, but a significant association between prolapse and urinary leakage was not identified [Seim et al. 1996].

Procedure for Physical Examination

Procedure for Physical Examination

The physical examination is the foundation of targeted and problem-oriented treatment. It follows history taking and an introductory patient education session, during which the patient is informed explicitly and in detail about the examination procedures and treatment options.

Vaginal Examination of the Pelvic Floor

Vaginal Examination of the Pelvic Floor

The method of vaginal examination of the pelvic floor is an essential element of the physiotherapeutic examination procedure in patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. The method was developed as a means of establishing whether the muscles of the pelvic floor are contracting correctly [B⊘ et al. 1988, Bump et al. 1991]. Only thoroughly trained physiotherapists should conduct the examination.

A prerequisite for vaginal examination of the pelvic floor is that the patient should be informed about the purpose of the examination and should provide unrestricted consent in writing. The therapist must note any nonverbal indications of discomfort that might call into doubt a verbal consent that has already been given [Haslam 2001].

In some European countries, the legal position in relation to a therapist’s authorization to carry out a transvaginal examination of the pelvic floor is unclear. For reasons of legal protection, it is recommended that the patient’s unrestricted agreement should be documented in the form of clear written consent. In cases of doubt, the national specialist organizations for physical therapists who are active in urogynecology and obstetrics should be consulted.

In some European countries, the legal position in relation to a therapist’s authorization to carry out a transvaginal examination of the pelvic floor is unclear. For reasons of legal protection, it is recommended that the patient’s unrestricted agreement should be documented in the form of clear written consent. In cases of doubt, the national specialist organizations for physical therapists who are active in urogynecology and obstetrics should be consulted.

Purpose of the Examination

The purpose of the examination is to assess the ability of the muscles of the pelvic floor to contract voluntarily so that an individually adapted exercise program can be prescribed. The patient should be given feedback on her ability to contract and relax her pelvic floor muscles voluntarily. The examination is then used to show the patient visible changes in the position of the vaginal walls and the perineum, both at rest and while straining, using a hand-held magnifying mirror. In patients who have deficient sensation in the pelvic floor muscles, the vaginal examination also serves as an aid to perception.

Preparation for the Examination

Before the start of the examination, the proposed procedure and its purpose are explained once again to the patient, who has already received information about them. She is told that she can have the procedure stopped at any time. The patient may bring a companion to be present at the examination, or request the presence of another member of staff [Haslam 2001]. The examination takes place in a well-lit room that can be locked. The patient should be able to undress and dress without being disturbed, and washing facilities should be available.

For the examination, the patient lies on her back, with the lower body exposed and a sheet under the buttocks. The legs are abducted and drawn up [Haslam 2001]. If there is a problem with relaxation [Wennergren et al. 1991], the legs can be supported with a pad or a pillow. The position of the lumbar spine is adjusted. The therapist explains each step in the course of the procedure. The patient’s face should be monitored for any signs of discomfort.

Procedure for Vaginal Examination of the Pelvic Floor

Procedure for Vaginal Examination of the Pelvic Floor

- Inspection

- Findings on vaginal palpation

- Assessment of muscular function

- Evaluation of the degree of descent

- Measurement of vaginal pressure

- Feedback to the patient concerning the findings

- Documentation

Inspection

Observation of the external structures provides information about the condition of the skin, perineal scars, and the trophic status of the vaginal introitus, as well as about the distance between the posterior commissure and the external urethral meatus, the elevation of the perineum above the opening of the introitus, and whether signs of descent are evident at rest and without load.

The patient is requested to contract the muscles of the pelvic floor (“like lifting up inside, a closing round the entrance to the vagina, and drawing the anus in”), and the perineum and labia are observed. If the contractions are correct, visible changes include posterior displacement of the clitoris, narrowing and inward movement of the introitus, a shortening and drawing upward and forward of the perineum, retraction of the anus, and increased wrinkling around the anus. Visible synergic contractions of the adductors, gluteals, or rectus abdominis are not correct [Morkved and B⊘ 2000]. If the perineum descends or the introitus opens, the movement is paradoxical movement and indicates that the patient is not straining correctly.

When the patient is requested to cough, attention focuses on the presence of a reflex contraction, the type and extent of perineal movement, urinary leakage, and signs of descent. Signs of descent include loss of labial contact, opening of the introitus, gaping of the vagina, descent of the perineum, and prolapsing vaginal walls.

Findings on Vaginal Examination

The therapist thoroughly washes her hands, puts some lubricating gel on a tissue, puts on examining gloves, and applies the lubricating gel. The labia are separated, and the pad of the gloved index finger palpates slowly internally along the posterior side of the vagina to about 5cm [Haslam 2001]. The lateral vaginal walls are palpated by turning the finger from the 3-o–clock to the 9-o–clock position, looking for scars, tenderness, and changes in sensation. The muscular volume and contours of the levator ani on the left and right are assessed in particular, and differences between the sides are noted. Wasting of the pubococcygeus is often unilateral and more prominent on the right. Healthy pelvic floor muscles feel full and tensely elastic, and exert pressure on the palpating finger when contracted (Fig. 4.44). Prolapse of the anterior and/or posterior vaginal walls can be felt as a bulging of the tissue, while uterine prolapse is present when the tip of the finger meets the cervix prematurely [Haslam 2001]. The cervix can be distinguished by feel from the surrounding tissue, because it is firmer and tenser.

The stability of lubricating gel is limited. Tubes that have been opened should be discarded after one week [Haslam 2001]. If they are only rarely used, single-use packages are more suitable. If either the patient or the therapist is allergic to latex, non-latex gloves should be used. Sterile gloves are only required in exceptional cases (e. g., postpartum).

The stability of lubricating gel is limited. Tubes that have been opened should be discarded after one week [Haslam 2001]. If they are only rarely used, single-use packages are more suitable. If either the patient or the therapist is allergic to latex, non-latex gloves should be used. Sterile gloves are only required in exceptional cases (e. g., postpartum).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree