Principles, Planning, and Decision Making

Neil Dion

Young-Min Kwon

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective and reliable procedure for pain relief in patients with degenerative joint disease (DJD) of the hip. A report from the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 332,000 THA were performed in the United States in 2010. Complication rates remain low, but morbidity and mortality do occur after THA. These include instability, infection, venous thromboembolism, leg length inequality, and fracture.

Preoperative planning is important to minimize potential complications. It allows the surgeon to appropriately prepare for surgery by ensuring that all tools and implants that may be required are available. Additionally, it allows one to improve efficiency in the operating room. While the preoperative plan often focuses on the template for component sizing, a thorough surgical plan encompasses much more than this.

Successful outcome after THA requires the selection of appropriate patients preoperatively. Identification of candidates for arthroplasty is based on history, physical examination, radiograph interpretation, and medical decision making. An attempt at conservative management of symptoms should be made prior to elective arthroplasty. Alternative surgical management should be considered if appropriate. Medical assessment should be performed to optimize the patient’s condition

and decrease the risk of nonorthopedic complications. After an appropriate patient decides to undergo surgery, planning for the procedure involves identification of the appropriate style and size of implants through templating of radiographs. Digital and acetate overlay techniques will be discussed. An appropriate operative approach should be chosen. The patient should be counseled as to the expected course and outcomes as well as the potential complications prior to undergoing surgery. Attention to all of these factors in the preoperative setting will help to optimize the likelihood of a successful outcome.

and decrease the risk of nonorthopedic complications. After an appropriate patient decides to undergo surgery, planning for the procedure involves identification of the appropriate style and size of implants through templating of radiographs. Digital and acetate overlay techniques will be discussed. An appropriate operative approach should be chosen. The patient should be counseled as to the expected course and outcomes as well as the potential complications prior to undergoing surgery. Attention to all of these factors in the preoperative setting will help to optimize the likelihood of a successful outcome.

Clinical History

The diagnosis of hip pathology amenable to THA begins with obtaining an accurate history. It is important to have the patient specifically identify the location of the symptoms. Anterior groin pain is the most reliable location of pain for intra-articular hip pathology. Lumbar spine pathology can often present as posterior hip pain or buttock pain that patients refer to as hip pain; however, some patients with DJD of the hip do experience posterior hip pain. This can be investigated further by having the patient describe the nature of the pain. Pain that is associated with low back pain sometimes presents with a sensory deficit or focal muscle weakness. Pain radiating past the knee should raise one’s suspicion of a lumbar etiology. Pain in the thigh or calf that is worse with prolonged activity is suggestive of vascular or neurogenic claudication.

The clinician should determine the duration of the symptoms as well as the severity. One must get a sense for the patient’s predisease activity level and the extent to which symptoms are affecting the patient’s quality of life. The use of ambulatory aids should be discussed. Understanding the patient’s activity level will help determine the severity of the symptoms as well as determine reasonable goals for activity level after surgery.

A detailed medical history should be obtained. One should focus on conditions that may make a patient a poor candidate for THA. Patients with significant medical comorbidities may be poor candidates for general anesthesia. Patients who have neuromuscular conditions or a history of alcohol or drug abuse may be at increased risk for dislocation postoperatively. Immunocompromised and patients who abuse intravenous drugs are at a heightened risk of infection. Obesity can make arthroplasty technically challenging and increase the likelihood of complications. Clinicians should have a discussion with patients with chronic pain and opiate use about reasonable expectations after hip arthroplasty. This can help prevent frustration for both the patient and the surgeon postoperatively.

Pain localized to the groin is commonly associated with hip pathology. Other extrinsic intrapelvic pathology can also present with groin pain, however, including inguinal hernia, retrocecal appendix, and ovarian cyst. Occasionally, hip pathology will present with knee pain in a patient who has normal knee radiographs and a normal knee exam but abnormal hip radiographs. This is referred pain due to the innervation pattern of the anterior division of the obturator nerve. The symptoms are frequently reproduced with hip rotation, axial load, or assisted hip flexion and hip internal rotation. On occasion, it may be prudent to utilize intra-articular injection of the hip under fluoroscopy to confirm that knee pain is referred from the hip. Elimination of the knee pain with a hip injection helps confirm that diagnosis.

Physical Examination

Physical exam is useful for making a diagnosis and planning a successful THA. Physical examination findings that support that the hip is the origin of the symptoms include pain that is reproduced by resisted hip flexion (positive Stinchfield test). Pain and limitation of motion, particularly flexion and internal rotation, are common in DJD.

Physical examination findings such as a neurologic deficit, a positive straight leg raise, and diminished Achilles or patellar tendon reflex will also help distinguish lumbar pathology from pain emanating from the hip joint. Degenerative arthritis of the spine and hip frequently coexist, and an epidural steroid injection or intra-articular hip injection may be useful for diagnostic purposes in these scenarios.

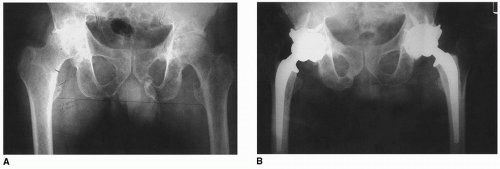

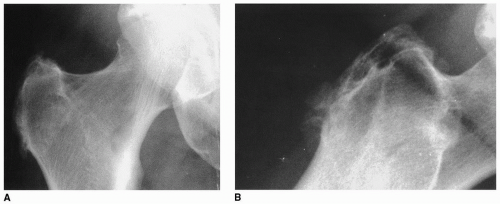

Once it has been determined that the hip is the source of symptoms, it is important to determine whether the pathology is intra-articular or extra-articular in origin. Causes of extra-articular hip pain include trochanteric bursitis, piriformis syndrome, psoas bursitis or tendonitis, and abductor strain or tendonitis. Pain that is located directly over the trochanter that is worse with resisted hip abduction is the hallmark of trochanteric bursitis. Plain radiographs should be scrutinized for irregularity

about the greater trochanter (see Fig. 11-1). A local injection into the area of maximal tenderness laterally over the trochanter will frequently alleviate the symptoms.

about the greater trochanter (see Fig. 11-1). A local injection into the area of maximal tenderness laterally over the trochanter will frequently alleviate the symptoms.

FIGURE 11-1 AP (A) and lateral (B) radiographs of the hip of a patient with localized trochanteric pain showing bony irregularity typical of trochanteric bursitis. |

The skin and soft tissue about the hip should be inspected. Previous incisions should be evaluated for the possibility of incorporation into the planned operative incision. Body habitus should be noted. BMI should be documented as values greater than 40 have been associated with increased complication rates. The distribution of adipose tissue should be inspected. The remainder of the extremity should also be evaluated to document both the neurovascular status and the presence of distal extremity infections.

The patient’s standing posture should be noted. Patients with excessive lumbar lordosis have a different orientation of the acetabulum in the erect posture. These patients have differences between the anatomic and functional anteversion of their acetabulum. This can have a significant effect on stability. It may be advisable to place the acetabular component in more anteversion to compensate for the change in orientation of the acetabular component that occurs when a patient is upright. The iliac crest should be observed from behind for the presence of pelvic obliquity. This may result in an apparent limb length discrepancy. The block test is frequently used as a clinical measurement. It is important to correlate the patient’s own feeling about limb length with the measurements taken with blocks. It is important to inform patients that apparent limb length discrepancy secondary to the lumbar spine may not be correctable at the time of hip replacement.

The surgeon should have an objective plan and strategy for the correction of limb length discrepancy. Following limb length assessment, the patient’s gait should be observed for gait patterns, including antalgic, short limb, or Trendelenburg gait. The Trendelenburg test can also be performed as a clinical evaluation of abductor muscle weakness. This should be correlated with the observation of gait and manual muscle testing of abductor strength against resistance in the side-lying position. Patients with substantial muscle weakness should be evaluated for an underlying cause. Some degree of weakness can be secondary to pain; however, the inability to resist gravity in side-lying abduction is unusual, and an explanation should be sought. The presence of significant abductor weakness may be relevant in the operative plan. Strategies such as increasing lateral offset or lateralizing the trochanter may be advisable in the presence of significant laxity or weakness in the abductors. It also may be advisable to use an acetabular component that can accommodate a constrained liner in the event that a patient with severely compromised abductors has postoperative instability.

Rotational deformities may be revealed on observation of gait. Patients with intoeing may also have increased femoral anteversion. This can also be determined by the presence of excessive passive internal rotation of the femur in combination with limited external rotation. This condition is usually bilateral, and patients should be advised that limb rotation may be somewhat asymmetric postoperatively. Excessive femoral anteversion should be considered in implant selection and acetabular component positioning as well.

Physical examination of the contralateral hip and other joints also significantly impacts the preoperative plan. If the patient has severe bilateral hip involvement that would preclude ambulation postoperatively, bilateral hip replacement should be considered. The status of other joints is particularly relevant in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, who frequently have other joints involved. If the upper extremities are involved to the extent that it would prevent postoperative ambulation with assistive devices, typically, the upper extremity should be addressed first. Likewise, a plantigrade foot is essential for effective ambulation. If foot or ankle pathology does not allow normal plantigrade gait, then corrective foot or ankle surgery prior to hip replacement should be considered. When hip and spine pathology are concomitant, THA often precedes surgical treatment of the spine. When both the ipsilateral hip and knee joints are markedly symptomatic, hip replacement is generally performed prior to knee replacement; however, there are exceptions. In patients with severe flexion contractures of the knees that will prevent ambulation, consideration should be given to performing knee arthroplasty prior to hip replacement.

Differential Diagnosis

Although degenerative osteoarthritis is the most common cause for the need for THA, there are a number of other diagnoses that have implications on the preoperative assessment. These include osteonecrosis (ON), inflammatory arthritis, dysplasia, metastatic disease, occult infection, and occult trauma. In patients who have ON, it is important to determine the etiology of the process. When an etiology can be determined, the most common are trauma, alcohol use, and steroid use. Patients with a history of heavy alcohol use may need treatment for this prior to undertaking a major elective procedure. Sobriety also decreases the likelihood of instability postoperatively. Patients with hypercoagulable conditions often require anticoagulation or placement of an inferior vena cava filter prior to THA. Patients with sickle cell anemia are more likely to require transfusion. ON is frequently bilateral. A patient with early stage ON in the contralateral hip may be a candidate for core decompression or some other head-sparing procedure either prior to the contralateral hip replacement or concomitantly.

Patients with inflammatory arthritis have a number of relevant associated findings that impact preparation for hip replacement. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis frequently have involvement of the cervical spine and/or temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Flexion/extension lateral radiographs to evaluate C1-2 instability should be considered. Patients with symptomatic C1-2 instability should have this assessed prior to hip replacement. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis may be on immunosuppressive agents such as corticosteroids. This may require a stress dose of steroids perioperatively to avoid Addisonian crisis. Rheumatoid patients may also be on immunosuppressive agents such as methotrexate or disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) including etanercept. The medications vary, but for some of them it is prudent to discontinue the medications for a period of time prior to elective surgery to minimize the risk of delayed wound healing or infection. Patients with gout, pseudogout, or other crystalline arthropathy may present with acute hip pain and chronic degenerative changes of the hip radiographically. If symptoms represent an acute flare of inflammatory disease, it is advisable to treat the flare appropriately before making further decisions about hip replacement.

Less common etiologies of presentation include Paget disease, infection, stress fracture, and occult hip fracture. The history and radiographs are crucial in considering these diagnoses. Metastatic disease should be considered in older patients with destructive lesions including a periacetabular lesion or a lesion in the intratrochanteric area. The most common primary malignancy involving bone is multiple myeloma, and it may present with anemia associated with hip pain. Myeloma lesions may involve the pelvis and can coexist with ON from the disease or its treatment. Patients with a history of trauma may have an occult hip fracture. Younger patients with a history of recent increase in activity such as military recruits or marathon trainees may be at risk for stress fracture of the femoral neck, which can present with groin pain. Older patients may exhibit the insufficiency fractures of pubic ramus. Making a specific diagnosis helps ensure that conditions associated with the disease process are identified and appropriately treated prior to consideration of a major elective procedure such as THA.

Selection of Appropriate Surgical Candidate

After a specific diagnosis has been made and all associated conditions have been assessed and treated, the next step is to determine whether the patient is an appropriate surgical candidate. The first criterion to satisfy is to determine whether there has been an adequate trial of nonoperative measures, such as anti-inflammatory medication, activity modification, and weight loss if appropriate. Patients can obtain substantial relief by unloading the joint with the use of a cane or avoiding highimpact activities and losing weight. Obese patients should be counseled as to the increased risks

associated with hip replacement in the presence of obesity and can be referred for counseling by a dietitian with the aim of supervised weight loss. Referral for bariatric surgery can also be considered in certain cases. If appropriate nonoperative measures have failed, it is next prudent to determine whether the patient is realistic regarding the risks, benefits, and limitations associated with the procedure.

associated with hip replacement in the presence of obesity and can be referred for counseling by a dietitian with the aim of supervised weight loss. Referral for bariatric surgery can also be considered in certain cases. If appropriate nonoperative measures have failed, it is next prudent to determine whether the patient is realistic regarding the risks, benefits, and limitations associated with the procedure.

It is important to determine what the patient’s requirements are regarding his or her vocation and activities following surgery. A patient who is a laborer who is required to do heavy lifting or running should understand that these activities are not generally advisable following hip replacement. It is also important to determine whether the patient will be compliant with activities such as avoiding extreme positioning during the first several months to minimize the risk of dislocation and to avoid high-impact activities to lower the risk of early failure due to polyethylene wear, lysis, and loosening.

There are certain patient characteristics that should be identified prior to major elective surgery. Patients who are seriously depressed should have this problem addressed prior to considering elective surgery. Counseling and medication may help address issues that are more important to the patient than their hip pain. In addition, patients who have significant psychosis or neurosis should be referred for evaluation and treatment to ensure that they are appropriately treated prior to considering hip replacement. Only patients who have the capacity to deal with potential complications should undergo THA. Patients with pending worker’s compensation claims have been associated with lower success rate. Other factors to consider are patients who are hostile or litigious. It is prudent to address these issues prior to proceeding with joint replacement.

It is crucial to determine if the patient is medically stable and optimal before a major elective procedure such as hip replacement. It is frequently advisable to have patients thoroughly evaluated by an internist to ensure that chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and pulmonary and cardiac disease are optimized prior to proceeding. It is also advisable to thoroughly screen patients for any potential source of hematogenous infection prior to hip replacement. The extremities should be assessed for cutaneous lesions such as venous stasis ulcers or infected toenails. These conditions should be treated prior to proceeding. Other potential sources of infection that should be addressed include urinary tract infection, prostatitis, periodontal disease, dental caries, and diverticulitis.

Nonarthroplasty Surgical Options

Once it has been determined that a patient is an appropriate surgical candidate, the next step is to determine the most appropriate surgical intervention for each individual patient. Before proceeding with hip replacement, it is advisable to consider nonarthroplasty surgical options. Patients with symptoms of a labral tear or loose body may be candidates for arthroscopy. In the presence of early degenerative changes with maintenance of articular cartilage and mechanical abnormalities, pelvic or femoral osteotomy may be an option. The indications for hip resurfacing are currently quite narrow; however, it remains an option in a limited subset of male patients with underlying diagnosis of osteoarthritis. In the young active patient with unilateral hip disease and complete loss of articular cartilage, arthrodesis may be considered. A resection arthroplasty is rarely performed as a salvage procedure in patients who are poor ambulatory candidates.

Radiographic Evaluation

The first step in preoperative radiographic analysis involves obtaining consistent, appropriate radiographs for review. A minimum of two views is required, one in the anteroposterior (AP) projection and one lateral view. In practice, three views are preferable. An AP view of the pelvis is necessary to estimate relative limb length. A more accurate assessment of the dimensions of the proximal femur is obtained from an AP view centered over the hip. The standard distance from the x-ray tube to the tabletop is 40 inches. If a grid cassette is placed directly beneath the hip, magnification of the bones of approximately 10% is seen in an average-size patient. Placing a cassette directly beneath the extremity is common in the operating room, but in most radiology departments, a Bucky tray is placed in a compartment approximately 2 inches below the tabletop, resulting in magnification of 15% to 20% (1). The degree of magnification is directly related to the distance from the bone to the cassette. In an obese patient, therefore, the magnification can be over 25%, whereas in a thin patient, it can be less than 15%. A magnification maker can be utilized to quantify the degree of magnification. This is particularly useful for templating sizes of implants.

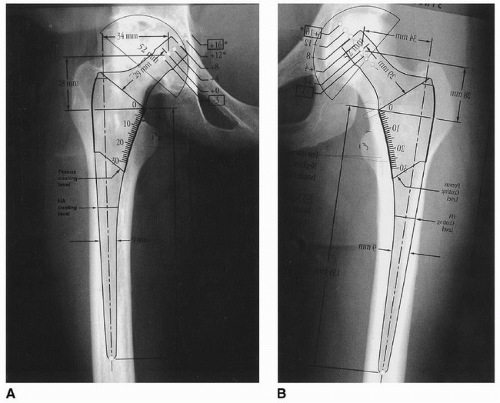

The AP pelvis and hip radiograph should be obtained with the patient lying flat on the table and the lower extremities internally rotated 15 degrees. Internal rotation brings the femoral neck into a parallel orientation relative to the cassette and thus perpendicular to the x-ray tube in the average patient. This gives a more accurate depiction of the proximal femoral geometry and true femoral offset. Patients tend to naturally assume a posture of external rotation of the hips when lying supine. In addition, patients with degenerative disease tend to develop external rotation contractures, accentuating the tendency

for AP radiographs to be taken with the hip externally rotated. Radiographs in external rotation make the intertrochanteric area appear more narrow, the femoral offset less, and the lesser trochanter more prominent. Internal rotation has the opposite effect: increasing the offset, making the intertrochanteric area larger, and making the lesser trochanter much less prominent (see Fig. 11-2).

for AP radiographs to be taken with the hip externally rotated. Radiographs in external rotation make the intertrochanteric area appear more narrow, the femoral offset less, and the lesser trochanter more prominent. Internal rotation has the opposite effect: increasing the offset, making the intertrochanteric area larger, and making the lesser trochanter much less prominent (see Fig. 11-2).

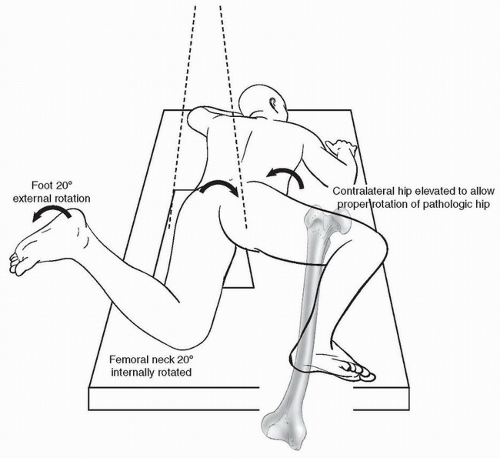

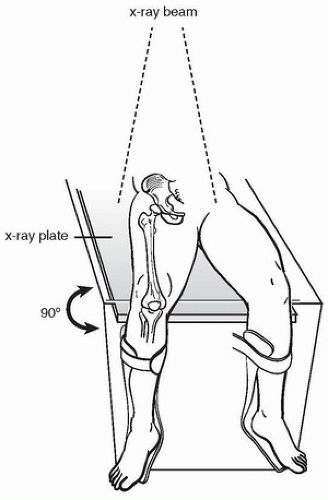

If a flexion contracture is present as noted on physical examination, the radiographic technique can be modified. If a standard AP radiograph is obtained in the presence of a flexion contracture, typically, the femur will be off of the tabletop with the patient supine, or there will be increased lumbar lordosis. If the hip is flexed for an AP radiograph, it will result in a greater degree of magnification and often rotation of the femur as well. These inaccuracies can be minimized by obtaining the AP radiographs in a semisitting position (see Fig. 11-3). Rotation of the femur has a significant effect on the measurement of both the neck-shaft angle and femoral offset.

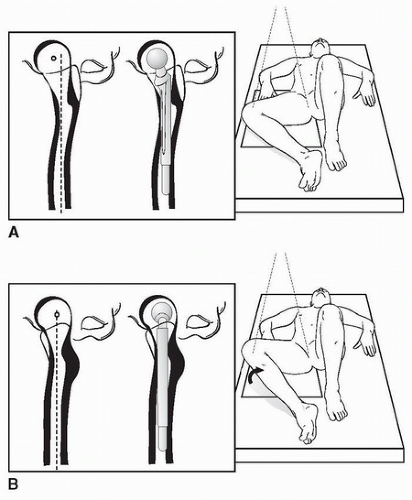

As a result of all of these factors, preoperative planning based on malrotated radiographs is inaccurate and will provide suboptimal information for the preoperative plan. If the pathologic hip cannot be internally rotated 15 degrees, templating can be done on the contralateral normal or less involved

side (see Fig. 11-4). This assumes that the internal geometry of the contralateral hip is an accurate representation of that of the pathologic hip, a supposition that has been supported by a number of authors (2,3). In many cases, however, both hips have external rotation contractures. In such cases, a posteroanterior radiograph can be obtained with the patient placed prone, with the affected limb in 15 to 20 degrees of external rotation and the hip directly against the tabletop (see Fig. 11-5).

side (see Fig. 11-4). This assumes that the internal geometry of the contralateral hip is an accurate representation of that of the pathologic hip, a supposition that has been supported by a number of authors (2,3). In many cases, however, both hips have external rotation contractures. In such cases, a posteroanterior radiograph can be obtained with the patient placed prone, with the affected limb in 15 to 20 degrees of external rotation and the hip directly against the tabletop (see Fig. 11-5).

FIGURE 11-3 Positioning of the patient with flexion contracture of the hip and/or knee. (From Engh C, Bobyn LD, eds. Biological fixation in total hip arthroplasty. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1985:47.) |

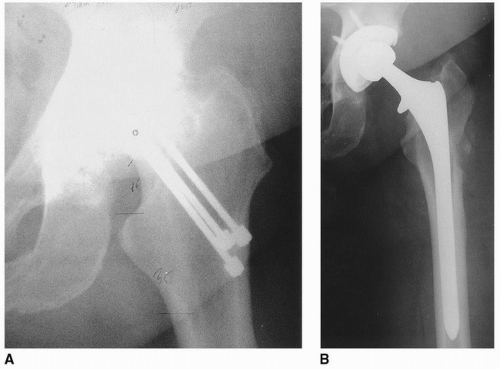

FIGURE 11-6 A: Preoperative radiograph demonstrating multiple pins embedded in bone. B: A long cementless stem was elected to bypass the femoral window necessary to remove the pins. |

If there has been a previous fracture or osteotomy, long films of the entire femur are advisable. A standing film that includes the hip, knee, and ankle will give a more accurate assessment of the effect of the angular deformity on the overall limb alignment. Previous internal fixation devices may require special equipment for removal as well as special components to compensate for bone loss from component removal (see Fig. 11-6). Additionally, this should alert the physician that infection should be ruled out prior to elective THA.

Many authors advocate a modification of the frog-leg lateral for preoperative planning: the table-down or Löwenstein lateral x-ray. This is obtained with the patient supine and the hip externally rotated such that the hip, knee, and ankle are contacting the tabletop (see Fig. 11-7A). The femur is usually closer to the table in this position than in the standard AP radiograph, because the distance to the femur is less and results in less magnification. This projection is best for determining the maximum bow of the femur and estimating the true degree of anteversion of the femoral neck. To obtain an orthogonal view to the AP projection with the limb internally rotated, the knee can be lifted at an angle of 15 to 20 degrees from the tabletop (Fig. 11-7B).

General Radiographic Review

Once standard radiographic views are obtained, it is appropriate to review the films in a general way to confirm the original or working diagnosis prior to embarking on preoperative planning. If the trabecular pattern is coarsened and irregular, for instance, Paget disease should be considered. Laboratory values from serum and urine may be appropriate to determine if the patient is in the active, lytic phase of the disease, in which case medical treatment with deferral of surgery may be appropriate. This would also alert the surgeon to carefully review long films of the femur in the AP and lateral projections for bowing, which could make stem insertion difficult. It may be difficult to distinguish bone pain from Paget disease from the accompanying DJD. Intra-articular injection of a local anesthetic has been suggested as a method of making this distinction (4).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree