5 Cyriax had a straightforward opinion about treating orthopaedic problems: It is obvious that the method of treatment will depend largely on the existing type of disorder. In orthopaedic medicine, disorders may be grossly categorized as follows: • Traumatic – an injury resulting either from one single trauma or from multiple small traumas, the so-called overuse injuries • Inflammatory – rheumatoid: poly- or monoarticular, infectious, traumatic • Internal derangement – loose bodies and displaced menisci in peripheral joints and intervertebral disc displacements in the spine • Functional disorders – instability, weakness, proprioceptive disturbances • Psychogenic pain – there is no existing functional or anatomical explanation for the pain. • Manipulation techniques (rapid, small-amplitude, thrusting passive movement – also called ‘grade C mobilization’) are used to reduce small cartilaginous displaced fragments both in the spine and in peripheral joints (loose bodies). Manipulation is also called for to restore normal mobility in a joint restricted by ligamentous adhesion and in subluxation of bones. • Gentle passive mobilizations (grade A and B mobilizations) are used to stretch capsular adhesions and to improve the function of ligaments and tendons. In the treatment of traumatic injuries they are often used in combination with deep transverse massage. • Active movements and proprioceptive training are needed in the treatment of functional disorders and instability. In the treatment of minor muscular tears they are very useful in avoiding the formation of abnormal intralesional adhesion formation. • Injection and infiltration techniques are used to reduce traumatic or rheumatoid inflammation. They are most valuable in arthritis, bursitis, ligamentous and tendinous lesions and in neurocompression syndromes. • Deep friction is a very useful technique in treating traumatic and overuse soft tissue lesions. The rationale for using deep friction (which is in fact a form of soft tissue mobilization) is supported by experimental studies of the past several decades that confirm and explain the beneficial effects of activity on the healing musculoskeletal tissues (see Connective tissue). Repair and remodelling of healing tissues respond to cyclic loading and motion.1 Early motion and loading of injured tissues is not without risk, however, and excessive loading can inhibit or stop healing. Deep transverse friction imposes cyclic loading without bringing too much tension on the healing longitudinal structures of tendon or ligament and can therefore be considered as beneficial. Deep transverse friction (although the word friction is technically incorrect and would be better replaced by ‘massage’) is a specific type of connective tissue massage2 developed in an empirical way by Cyriax.3 Transverse massage is applied by the finger(s) directly to the lesion and transverse to the direction of the fibres. It can be used after an injury and for mechanical overuse in muscular, tendinous and ligamentous structures.4–6 In many instances the friction massage is an alternative to infiltrations with steroids. Friction is usually slower in effect than injections but leads to a physically more fundamental resolution, resulting in more permanent cure and less recurrence. Whereas steroid injection is usually successful in 1–2 weeks, deep friction may require up to 6 weeks to have its full effect. Only a few studies exist,7,8,9 and more research is urgently needed. However, experienced therapists know in what kind of soft tissues they can expect good results with transverse massage and where the technique does not work. Transverse massage either is effective quickly (after 6–10 sessions) or not at all. Advice on indications, contraindications and modalities of the technique that are given in this book rely solely on the experiences of the authors and not on scientific research. It is a common clinical observation that application of local transverse friction leads to immediate pain relief – the patient experiences a numbing effect during the friction and reassessment immediately after the session shows reduction in pain and increase in strength and mobility. The time to produce analgesia during the application of transverse friction is a few minutes and the post-massage analgesic effect may last more than 24 hours.10 The temporary relief at the end of a session may prepare the patient for treatment with mobilization not otherwise possible, such as selective rupture of unwanted adhesions. • Pain relief during and after friction massage may be the result of modulation of the nociceptive impulses at spinal cord level: the gate control theory (see Ch. 1). The centripetal projection into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord from the nociceptive receptor system is inhibited by the concurrent activity of the mechanoreceptors located in the same tissues. Selective stimulation of the mechanoreceptors by rhythmical movements over the affected area thus ‘closes the gate for pain afference’. • According to Cyriax, friction also leads to increased destruction of pain-provoking metabolites, such as Lewis’s substances. This metabolite, if present in too high a concentration, provokes ischaemia and pain.3 • It has also been suggested that prolonged deep friction of a localized area may give rise to a lasting peripheral disturbance of nerve tissue, with local anaesthetic effect. • Another mechanism through which reduction in pain may be achieved is through diffuse noxious inhibitory controls, a pain-suppression mechanism that releases endogenous opiates. The latter are inhibitory neurotransmitters that diminish the intensity of the pain transmitted to higher centres.11–13 Connective tissue regenerates largely as a consequence of the action of inflammatory cells, vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells and fibroblasts. Regeneration comprises three main phases: inflammation, proliferation (granulation) and remodelling. These events do not occur separately but form a continuous sequence of changes (cell, matrix and vascular changes) that begins with the release of inflammatory mediators and ends with the remodelling of the repaired tissue (see Ch. 3). Friction massage may have a beneficial effect on all three phases of repair. It has been suggested that gentle transverse friction, applied in the early inflammatory phase enhances the mobilization of tissue fluid and therefore increases the rate of phagocytosis.14 During maturation, the scar tissue is reshaped and strengthened by removing, reorganizing and replacing cells and matrix.15 It is now generally recognized that internal and external mechanical stress applied to the repair tissue is the main stimulus for remodelling immature and weak scar tissue – with fibres that are oriented in all directions and through several planes – into linearly rearranged bundles of connective tissues.16 Therefore, during the healing period, the affected structures should be kept mobile by normal use. However, because of pain, the tissues cannot be moved to their full extent. This problem can be solved by friction. Transverse friction massage imposes rhythmical stress transversely to the remodelling collagenous structures of the connective tissue and thus reorients the collagen in a longitudinal fashion. Friction is thus a useful treatment to apply early in the repair cycle (granulation and beginning of remodelling stage): the cyclic loading on and motion of the healing connective tissues stimulates formation and remodelling of the collagen.17 At a later stage when strong crosslinks or adhesions have formed, more intense friction is needed to break these down.18–21 The technique is then used to soften the scar tissue and to mobilize the crosslinks between the collagen fibres and the adhesions between healing connective tissue and surrounding tissues. This, together with the local anaesthesia produced, prepares the structures for mobilizations that apply longitudinal stress to the structures and rupture the larger adhesions. Theoretically, friction can be used for all muscle belly lesions. However, some lesions respond so well to local anaesthetic infiltration that friction is not used. This is the case in type IV tennis elbow (lesion at the muscle belly of the extensor carpi radialis). On the other hand, sometimes no alternatives exist to treatment with deep transverse friction (Box 5.1). A lesion of the subclavius or intercostal muscles for instance can be treated only by deep transverse friction. Lesions at the tenoperiosteal insertion can be treated either with corticosteroid infiltrations or with deep transverse massage. Corticosteroid suspension quickly converts an inflamed and painful scar into one free of inflammation. However, the recurrence rate is rather high, between 20% and 25%.3 The aim of the massage is to get rid of the self-perpetuating inflammation by breaking up the disorderly scar tissue and adhesion formation by converting it into properly arranged longitudinal connective fibres. This takes longer but once cure is achieved there will be less of a tendency towards recurrence. It may therefore be a policy to start treatment with infiltrations but if the trouble recurs after a few months to substitute with massage. Lesions in the tendinous body, either traumatic or resulting from overuse, are contraindications for infiltration with corticosteroids. Ruptures have been reported after intralesional steroid infiltrations of long tendons and therefore deep frictions are the treatment of choice here.22,23 It has been explained (see Ch. 3) that early mobilization is extremely important for swift and full recovery of ligamentous sprains. However, in advocating this, one main difficulty is encountered: the intensity of the initial inflammatory reaction. The slightest movement causes pain which forces the patient to immobilize the joint and the ligaments. However, during immobilization, regenerating fibrils quickly start to form randomly organized scar tissue, leading to crosslinks and adhesion formation. This problem can be solved by gentle transverse frictions. Rhythmic movement across the inflamed ligament eases the pain and the tissue can be moved to and fro in an imitation of its normal behaviour. Deep transverse friction can be applied to the capsules of the trapezium–first metacarpal joint, the temporomandibular joint and the cervical facet joints. The indication is traumatic arthritis or osteoarthrosis. Results are fair, provided the arthrosis is not too advanced. Indications and contraindications to friction are outlined in Table 5.1. Three main techniques can be distinguished. These are used in the treatment of dense, round or flat collagenous bundles (tendons or ligaments) and in the treatment of tenosynovitis. The active phase is a sweep with the tip(s) of one or two digits across the tendinous structure. During the passive relaxation phase the finger is returned to the starting position, without losing contact between finger and skin. Movement is with the arm; friction is given by use of the pulpy part of the finger (Fig. 5.2). In large lesions, as in peroneal tendinitis, two or three adjacent fingers are used together. In deep-seated lesions as in tendinitis of the long head of biceps in the bicipital groove or at its insertion on the radius or in infraspinatus tendinitis, the thumb performs friction. Counterpressure is usually provided to enable a good sweep. The finger(s) applying counterpressure and stabilization are most important in bringing those applying friction into the right position and also determining the direction of the friction. The thumb is used (to give counterpressure) when the sweep is performed by a movement of the index reinforced by the middle finger or the middle finger aided by the index finger. When the thumb does the massage, counterpressure is from the fingers (Fig. 5.3). The most common way of applying friction around a round edge on a flat surface is to use the index reinforced by the middle finger. Sometimes the opposite is done: the middle finger is reinforced by the index. Sometimes counterpressure is not given, for example in friction to the quadriceps expansion or intercostal muscles. This technique is often used where the lesion is difficult to reach: the anterior aspect of the Achilles tendon, popliteus tendon and the dorsal interossei of the metacarpals. Massage is performed with the pulpy part of the third finger (long finger), reinforced by the index finger. The long finger is used because its long axis is the prolongation of the axis of pronation–supination rotation of the forearm (Fig. 5.4). This is the normal technique for a muscle belly. The pinch is between the thumb and the other fingers. The muscle is fully relaxed. The fingers are placed at one side of the affected area and the thumb at the opposite side (Fig. 5.5). By drawing the fingers upwards over the affected area, the therapist feels the muscle fibres escape from the grip until only skin and subcutaneous tissue remain. The amount of pressure applied depends on three elements: • The depth of the lesion: that friction must always reach sufficient depth to move the affected fibres in relation to their neighbours and sometimes the underlying bone or capsule, increased pressure must be applied to deeper structures. • The ‘age’ of the lesion: recent sprains and injuries require only preventive friction because crosslinks or adhesions have not had time to form. In long-standing cases more pressure is needed to get rid of these. However, pressure should always be associated with movement and should not replace it because pressure alone is both painful and ineffective. • The tenderness of the lesion: in severely inflamed lesions that are very tender to touch, friction with the usual amount of force may be very painful. Pain can be avoided by starting with a minimal amount of pressure – just enough to reach the lesion – and progressively increasing the force as treatment proceeds. Treatment is stopped once the patient is pain-free during daily activities and functional tests are totally negative. Local tenderness may persist longer but disappears spontaneously because it is the outcome of repetitive hard pressure. However, in a minor lesion of a muscle belly, massage is continued for 1 week after full clinical recovery to prevent recurrence (see Table 5.2; see also Box 5.2). • Grade A mobilization is a passive movement performed within the pain-free range. • Grade B mobilizations are passive movements performed to the end of the possible range. The latter is indicated by an end-feel. All stretching and traction techniques are grade B mobilizations. • Grade C mobilization is a minimal thrust with a high velocity and over a small amplitude. It is performed at the end of the possible range, i.e. the moment the therapist has reached the end-feel. Another word for grade C mobilization is manipulation. Passive movements within the pain-free range are usually called for in the treatment of injured connective tissue. A comprehensive literature evaluation and meta-analysis of experimental studies of the past several decades have demonstrated that regeneration of injured connective tissue is significantly better with the application of continuous passive motion. If the healing tissues are not loaded, regeneration results in unstructured scar tissue. Under functional load, the collagen fibres are oriented in a longitudinal direction and the mechanical properties are optimized.24 Grade A mobilizations are also used on the capsule of the shoulder in stage III arthritis when stretching and intra-articular steroids are contraindicated (see Ch. 14). In this condition, long-standing stimulation of the nociceptors has increased neuro-sympathetic activity, giving rise to vasoconstriction, muscle spasm and pain. Some cases of lumbago show persistent spinal deviation even after the pain has ceased. A quick thrust manipulation so effective in relief of pain is not effective in correcting the remaining deformity, but sustained translatory gliding in the opposite direction is most helpful. The movement is performed slowly and care is taken to keep the gliding within the pain-free range (see Ch. 40). • a limitation in the capsular pattern (see Ch. 4) • demonstration of a hard-elastic end-feel to restricted movements (see Ch. 4). In the very beginning of arthritis, muscle spasm forces the joint to be held in a position of ease, so restricting movement in some directions more than in others (see Capsular pattern, Ch. 4). Immobilization and inflammation cause disordered deposition of collagen fibres in the joint capsule and lead to the formation of capsular adhesions, which in turn are responsible for more restriction of movement and pain. Stretching aims at restoring mobility and function by breaking micro-adhesions and producing elongation of the shortened capsule. To be applicable, however, the ligamentous end-feel must be reached before the protective muscle spasm begins. To be successful, the therapist should therefore be able to differentiate between an elastic and a spastic end-feel. Capsular stretching can be preceded by application of heat, either through short-wave diathermy or ultrasound. This can relieve some pain and seems to lower the viscosity of the collagenous tissue, allowing more movement for less force. In vivo studies on the effects of heat on ligament extensibility have shown that sustained force applied after elevating tissue temperature produced significantly greater residual elongation.25,26 Traction is used to separate articular surfaces from each other and can be employed in two ways: as an accessory to manipulation or as the sole treatment. Reducing a displaced fragment is obviously easier when the bone ends between which it lies are pulled apart. If the fragment projects beyond the articular edge, tautening of the ligaments and capsule also provides a centripetal force. In that traction diminishes the pressure on the fragment, pain decreases, which allows the patient to relax the muscles more.18 In the cervical and thoracic spines, traction is a built-in safety measure for protecting the spinal cord during manipulation (see below) although the use of traction for this purpose and at these sites does not imply that manipulation can be performed on a basis of ‘try and see what happens’ without a proper diagnosis.27 In the spine, traction is used as the sole treatment only in nuclear disc protrusions, which are rare at the cervical and thoracic levels but are more common in the lumbar area. Spinal traction is always mechanical and is performed with the help of a harness (lumbar or low thoracic) or a sling (cervical or upper thoracic). Spinal traction distracts the intervertebral disc spaces. It also pulls the apophysial joints apart and slightly widens the intervertebral foramina.27–31 At the same time, negative intradiscal pressure is produced with centripetal ‘suction’ on any protrusion. The posterior longitudinal ligament is tightened, which may help reduce a displaced fragment. All these elements are helpful in the progressive reduction of a nuclear disc protrusion. Reduction of herniated bulges has been demonstrated on epidurography31–33 and on CT scan34 during and after traction. The effect of traction depends on the amount of force applied, the length of time per session, the interval between each session and the total number of sessions.35 A manipulation or grade C mobilization usually implies a single thrust of high velocity performed at the end of a passive movement after the ‘slack’ has been taken up, and over a small amplitude. It goes beyond the physiological limit but remains within the anatomical range. Precision of the movement and control of the applied force are required.36 Spinal manipulative therapy is a valuable method in the treatment of mechanical spinal disorders. Although it has not been scientifically validated, some studies have shown beneficial effect.37–40 However, its potential benefit should not be overestimated and the indications must be well defined and based on a sound clinical diagnosis. It must never be done as a test to see if it is effective. Therefore it should not be used on all those with back and neck pain although it may well cure a proportion who actually require it. To use McKenzie’s words: Even if you have a hammer in your hand not everything you see is a nail. Therefore indiscriminate use of spinal manipulative therapy must not be made if the criticisms that have been justifiably levelled at chiropractice and osteopathy are to be avoided. The development of postgraduate courses in manipulation is welcome, although some have overvalued the benefits of manipulative therapy. All who undertake manipulation have experienced the feeling of pride and joy in producing cure. It is the duty of those who have more experience of the benefits and limitations of manipulative therapy to moderate the understandable enthusiasm of those entering the field – a few successes may quickly lead to the temptation to manipulate every patient for any disorder.41

Principles of treatment

Introduction

Techniques

Deep transverse friction

Mode of action

Relief of pain

Effect on connective tissue repair

Friction stimulates phagocytosis

Friction stimulates fibre orientation in regenerating connective tissue

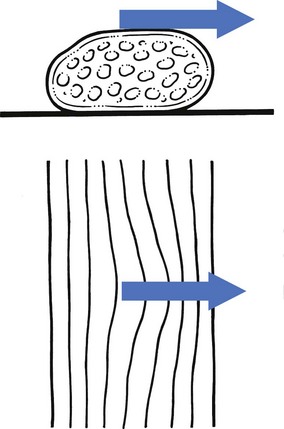

Friction prevents adhesion formation and ruptures unwanted adhesions (Fig. 5.1)

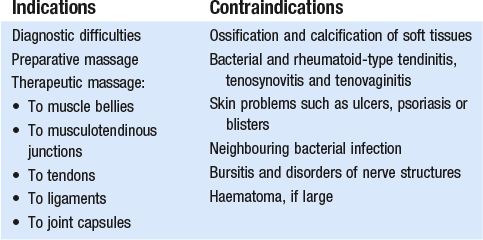

Indications

Therapy

Muscle bellies

Tendons

Ligaments

Joint capsules

Contraindications

Technique

Position of the therapist and the hands

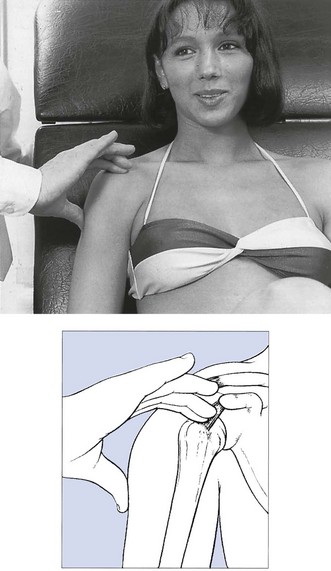

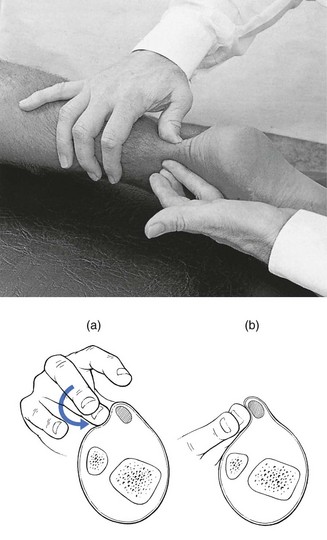

To-and-fro movements

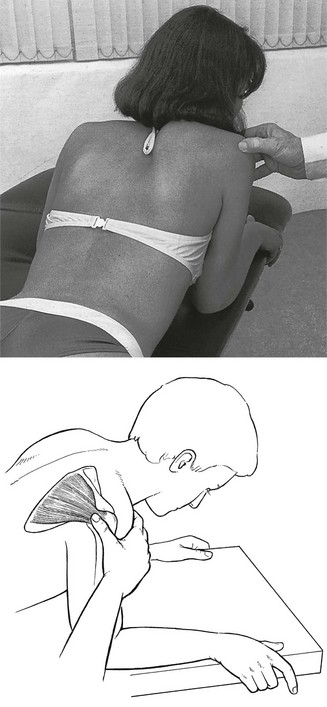

Pronation–supination

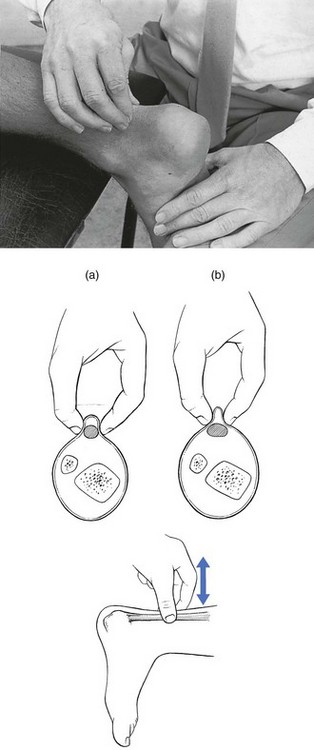

Pinch grip

Amount of pressure

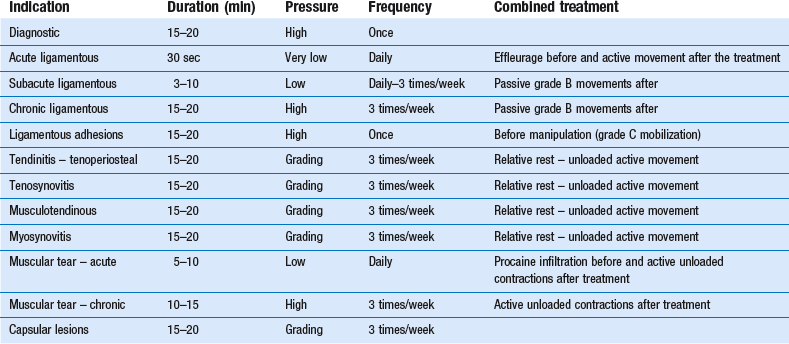

Duration and frequency

Passive movements

Indications

Grade A mobilizations

To promote healing of injured connective tissue

Distractions at the shoulder

Deformity correction

Grade B mobilizations

To stretch the capsule of a joint

Traction

Grade C mobilizations

Manipulation of the spine

Introduction

Principles of treatment