Principles of Hand Incisions

Marco Rizzo

William P. Cooney III

Indications/Contraindications

Because of the intricate balance of function in the hand and wrist, incisions in this area are unique. In an effort to ensure healing and maintain function, it is important to plan the incisions appropriately. The fingers have well-established approaches that allow for good visualization of deeper structures without compromising healing. Likewise, the hand and wrist are best approached while following basic principles. Poorly placed incisions result in restrictive scarring (Fig. 14-1), which may lead to diminished motion and function. In addition, the limited skin redundancy on the palmar surface of the hand may make delayed closure of edematous wounds difficult. Sound planning of incisions about the hand and wrist will help to avoid some of these difficulties. The purpose of this chapter is to review accepted incision designs for various aspects of the hand and wrist.

Preoperative Planning

Volar Approach to the Fingers

There are several commonly used approaches to the volar aspect of the fingers and thumb. The traditional Bruner incision is the approach that is most common (1). It is a zigzag incision that angles at the flexion creases of the metacarpophalangeal (MP), proximal interphalangeal (PIP), and distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints (Fig. 14-2). As the incision progresses proximally, the flexion creases of the palm are also points of direction changes. The principle is based on the fact that longitudinal incisions across these creases can generate excessive scarring and limit extension. For optimal healing of the flaps, it is best to keep the angles close to 90 degrees. Angles more acute than 60 degrees carry a higher incidence of skin necrosis.

FIGURE 14-1 Example of restrictive scar resulting from straight line incision placed over the flexor surface of the finger. |

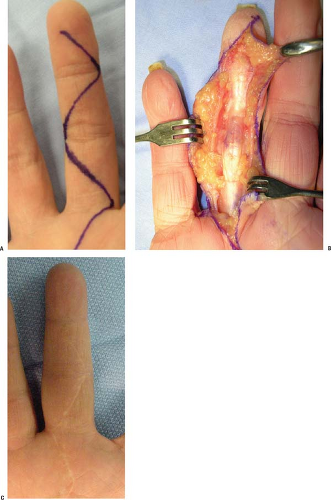

An alternative to the Bruner incision in the finger is the mid-lateral approach (Figure 3A). It has the advantage of being cosmetically more appealing. The incision is based about the lateral (or medial) side of the finger and the skin is elevated to provide exposure of the underlying tissues. A good way to ensure that the surgeon is not directly over the neurovascular bundles is to connect the incisions at the apex of the flexion creases (Fig. 14-3B). This is also a preferred approach in cases of replantation surgery. Although cosmetically appealing, the challenges of this technique include elevating the skin and ensuring its viability.

In cases of flexion deformity of the fingers such as Dupuytren’s contracture, a straight midline incision with z-plasties is an alternative approach to the traditional Bruner incision (Fig. 14-4). This will allow for the elongation of the incision as the flexion deformity is corrected. Angles of 60 degrees help preserve viability at the apex of the skin flap.

Incisions over the distal pulp of the finger, such as is necessary in felons, are best made directly over the area of swelling and induration. These wounds can be loosely closed or allowed to heal via secondary intention. If it appears that the incision may need to be extended proximal to the distal interphalangeal joint, a Bruner incision may be preferred for better exposure.

Dorsal Incisions About the Fingers

The dorsal skin of the hand lacks glaborous connections and has more redundancy, due to the requirements of joint flexion. Because of this redundancy, longitudinal incisions are acceptable. A longitudinal incision allows (Fig. 14-5) for protection of the venous and lymphatic drainage, while giving good visualization of the extensor mechanism (2). Lazy S or curvilinear incisions may also be designed to avoid crossing extension creases (see Fig. 14-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree