CHAPTER 1 General principles in the examination of a patient with an orthopaedic problem

In practice, the primary area of interest of the orthopaedic surgeon is in the joints of the limbs and spine, and how well they function. The major part of most orthopaedic examinations is therefore centred on the joint that troubles the patient, but the examination must often be extended to include the nerves and muscles that are responsible for movements in the joint; some of the patient’s other joints may also have to be checked to see if they are affected as well.

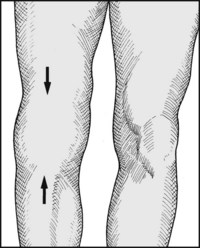

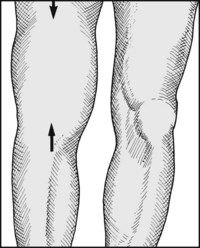

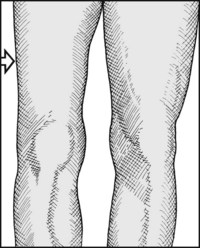

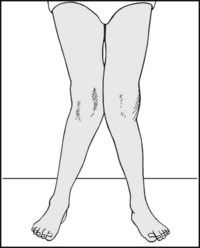

Step 1: Inspection

Look carefully at the joint, paying particular attention to the following points:

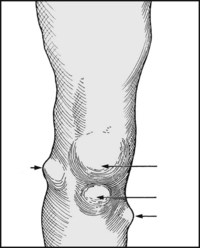

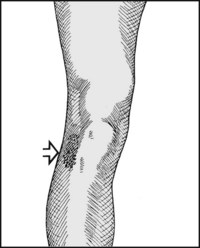

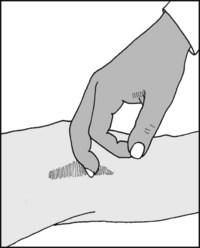

Step 2: Palpation

Some of the points you should note include the following:

1. Is the joint warm? If so, note whether the temperature increase is diffuse or localised, always bearing in mind the false impression that may be caused by the effects of local bandaging. A diffuse increase in heat occurs when a substantial tissue mass is involved, and is seen most commonly in joints involved in pyogenic and non-pyogenic inflammatory processes, and in cases where there is anastomotic dilatation proximal to an arterial block. Away from the joints themselves, infection and tumour should be borne in mind. A localised increase in temperature generally pinpoints an inflammatory process in the underlying anatomical structure. Asymmetrical coldness of a limb commonly occurs where the limb circulation is impaired, e.g. from atherosclerosis.