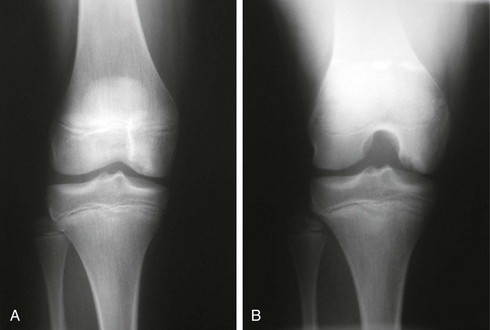

Chapter 65 Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) is a pathologic process that results in the detachment of subchondral bone and its overlying articular cartilage from the underlying bone.1–3 The destabilized area is now vulnerable to fragmentation and shear forces. The end result is degenerative changes and subsequent loss of function of the affected compartment. The cause remains unknown; however, it is likely multifactorial and may be related to repetitive microtrauma or an acute traumatic or ischemic incident, genetic predisposition, endocrine dysfunction, or an ossification abnormality.4–6 The prevalence of OCD is estimated at 15 to 30 cases per 1000 patients annually, affecting the medial femoral condyle (lateral aspect most commonly) in 80% of patients, lateral femoral condyle in 15%, and patellofemoral in 5%.7,8 Very little is known about the natural history of untreated OCD lesions. Studies by Lindén and colleagues7 and Twyman and colleagues9 suggest that patients with adult-onset OCD who are left untreated have a higher risk of developing osteoarthritis and that this likelihood is proportional to the side of the lesion. In effect, symptomatic lesions are always treated for fear of the sequelae of leaving these lesions to progress toward their inevitable osteoarthritic conclusion. The goal of reparative procedures is to restore the integrity of the native subchondral interface and preserve the overlying articular cartilage.10 Several options are available to treat adults with OCD, including debridement, drilling, loose body removal, microfracture, arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation (ARIF), osteochondral autografting and allografting, and autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI). Unfortunately, no consensus exists as to the best treatment option. The surgeon’s clinical expertise, the character of the defect, and the patient’s goals dictate the best treatment option. It is well established, though, that primary repair by rigid, compressive fixation of unstable lesions offers an attractive and effective means of treatment by preserving the native osteochondral surface. History and Physical Examination Physical examination is often more informative but can also be misleading. Observe for a change in gait, specifically an antalgic gait. There may be an effusion, loss in range of motion, and quadriceps atrophy depending on severity. Because the most common location for an OCD lesion is on the medial femoral condyle by the trochlea, tenderness may be elicited with palpation over this area and can be confused for patellofemoral pain. Observe for the Wilson sign—the patient will ambulate with the affected leg in relative external rotation to decrease contact of the lesion with the medial tibial eminence. Reproduction of pain through internal rotation of the tibia between 30 and 90 degrees of flexion and relief with subsequent external rotation is the Wilson test. It has low sensitivity, but if the result is positive initially, it reliably becomes negative with healing of the lesion.11,12 OCD lesions commonly appear as an area of osteosclerotic bone with a high-intensity line between the defect and the epiphysis (Fig. 65-1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most informative imaging modality, providing information on the quality of bone edema, subchondral separation, and cartilage condition, as well as lesion size, location, and depth. Meeting one of the following four criteria will provide up to 97% sensitivity and 100% specificity in predicting lesion stability (Fig. 65-2)13–16: 1. Thin, ill-defined or well-demarcated line of high signal intensity, measuring 5 mm or more in length at the interface between the OCD lesion and underlying subchondral bone 2. Discrete rounded area of homogeneous high signal intensity, 5 mm or more in diameter beneath the lesion 3. Focal defect with an articular surface of the lesion with a width of 5 mm or more 4. High–signal intensity line traversing the articular cartilage and subchondral bone plate into the lesion Initial conservative management is primarily activity modification with a reduction in weight bearing through use of crutches or possibly even casting in noncompliant patients. The goal is to allow time for lesion healing while limiting factors that may promote further degradation and separation. Radiographs are usually taken 3 months after the start of nonsurgical therapy to assess the status of the lesion and the condition of the subchondral bone. In a study by Sales de Gauzy and colleagues that looked at outcomes of OCD lesions in active children after cessation of sports activities, the researchers found an improvement in the lesions and recommended against surgical intervention.17 However, these results may not translate well to those who are not active sports participants. For these patients, limiting weight bearing and instructing on range-of-motion exercises to prevent stiffness may be viable options. An argument can be made, though, that nonsurgical management should be reserved for only skeletally immature patients because the risk of further degradation and loose body formation is high in adults. Surgical intervention is absolutely indicated if the lesion becomes detached or unstable or if the quality of pain worsens. The ideal OCD lesion for primary repair is the unstable lesion in situ in an active, symptomatic patient who acknowledges and is willing to comply with postoperative weight-bearing and activity restrictions and who understands the need for a second procedure for implant removal. In addition, patients who fail to demonstrate symptomatic or radiographic improvement after 6 months of appropriate nonoperative therapy should also be considered for surgical treatment. Primary repair is not recommended in the case of grossly unstable lesions that have produced a loose body with less than 3 mm of subchondral bone remaining on the fragment. These lesions may be treated with excision of the loose body and either marrow stimulation or one of a variety of secondary salvage cartilage restoration techniques. A cartilage flap can be fixed with screw or pin fixation, whereas a lesion that is partially lifted from the subchondral bone will require an intervention to improve bloodflow—usually via drilling or microfracture awl—followed by fixation.18 Furthermore, cancellous autograft is used in cases of subchondral bone loss to replace the lost subchondral support for the chondral surface. Results after primary repair of appropriately selected OCD lesions in the knee have typically been reported as good to excellent, with fragment union reported in 72% to 100% of patients.19–28

Primary Repair of Osteochondritis Dissecans in the Knee

Preoperative Considerations

Imaging

Indications for and Contraindications to Surgery

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine