CHAPTER 76 Primary Osteoarthritis: Ulnohumeral Arthroplasty

INTRODUCTION

Primary degenerative arthritis of the elbow is now well recognized and readily treated. Even today, the studies to better understand the condition are limited. Articular cartilage changes at the distal humerus40 and proximal radius with aging have been observed and studied.15 More recent experience with this condition has clarified to some extent the etiology and presentation, but the greatest advances are in the treatment of this disease. *

INCIDENCE AND ETIOLOGY

The existence of degenerative arthritis of the elbow has been recognized by orthopedic surgeons in the past, but the etiology was generally believed to be secondary to unrecognized or repetitive trauma. The radiographic characteristics have, however, been carefully delineated by Mianami et al in 1977.29 Furthermore, demographic studies have shown dramatic differences in the incidence of elbow arthritis in different races, but it is unclear if this is due to a genetic or an environmental influence.43 Smith50 clearly identified a condition that he termed osteoarthritis as a sequelae to trauma such as fracture-dislocation or “hard usage.” In fact, the condition as an overuse manifestation is rather well recognized,3,17,32 yet only brief references to the condition are noted in the standard texts.33,50 In addition to an increased awareness, there is some evidence that the actual incidence of the disease may be increasing.8

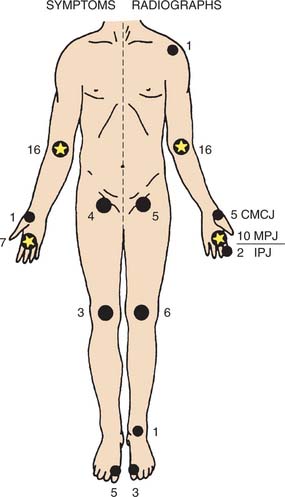

When discussed, it is thought to be related to a single or repetitive traumatic event or other predisposing conditions such as osteochondritis dissecans.21,50,57 We concur with this opinion as a cause, at least in some. Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow has been reported as accounting for 1% to 2% of patients presenting with elbow arthritis.7,18 This is consistent with the observation that less than 5% of joint replacement is performed in patients with this diagnosis.24,37 Doherty and Preston10 reported an incidence of about 7% from a typical rheumatologic practice and was shown to be associated with other sites of involvement, especially of the hand (Fig. 76-1). Because of these features, recognition of the entity is still sometimes overlooked or misinterpreted as a post-traumatic condition.11

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Men are, by far, more commonly affected with this condition than women at a ratio of about 4 to 1.11,19,29,31,38 The age at initial presentation is about 50 years,10 but I and others have observed a surprising variation ranging from 20 to 65 years.31,38 Occupations or avocations involving the repetitive use of an extremity are the most common factors, being present in about 60% of patients. We have diagnosed this problem in persons with neuropathic conditions causing impaired ambulation and requiring continued use of crutches or a wheelchair. The dominant extremity is involved in about 80% to 90% of patients, and bilateral involvement is present in 25% to 60%.10,38 The radiohumeral joint is involved in about 85%, but it may not be symptomatic.8

Stiffness may be a dominant feature.10 Loss of extension is the most common problem prompting medical attention, but mild to occasional moderate pain is also commonly present. The characteristic pain is of terminal extension in almost all patients and of terminal flexion in about 50%. Less commonly, symptoms are present throughout the arc. The intensity of pain is mild to moderate, and only occasionally is the process described as severe. The radiohumeral joint may be symptomatic in flexion, extension, and rotation.

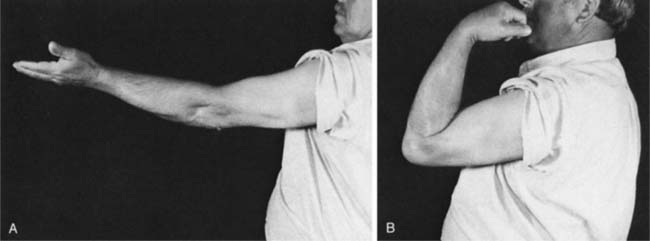

Consistent with these features, examination reveals an arc of motion that averages about 30 to 120 degrees (Fig. 76-2). Forearm rotation is not restricted or only minimally so because the radiohumeral joint is typically not severely involved. Because of excessive osteophyte formation, ulnar nerve irritation is observed in at least 10%31 and we suspect in a higher number if carefully examined. Ulnar nerve involvement should be specifically sought in the examination because it may influence treatment decisions and even long-term outcome.1

LABORATORY STUDIES

Because the diagnosis is not obvious owing to its relative infrequent occurrence, arthrocentesis, synovial biopsy, and arthroscopy have all been performed to diagnose this condition.11,39 When one is familiar with the disease, it comes as no surprise that all three of these diagnostic studies offer little if any added value.10,38 The roentgenographic study is diagnostic, and typically no other assessment is indicated or required. The sedimentation rate is normal.

RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES

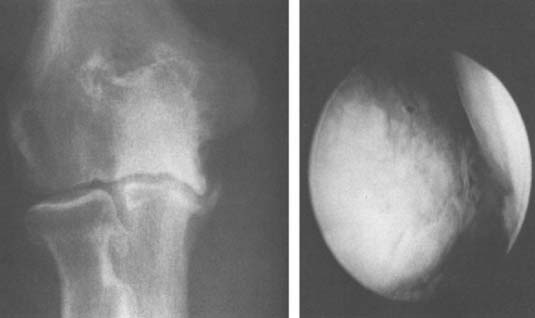

The roentgenographic features of this condition are classic and characteristic, maybe even monotonous. The characteristic of primary osteoarthritis of the elbow is “marginal osteophyte formation.” Hence, the consistent routine anteroposterior and lateral roentgenograms reveal an anterior osteophyte of the coronoid and a posterior osteophyte of the olecranon process (Fig. 76-3).29 The anteroposterior view also shows a consistent finding of ossification and osteophyte formation in the olecranon or coronoid fossa (Fig. 76-4). In the later stages, no other study is required to make this diagnosis. However, tomography may show subtle osteophyte formation, the presence and location of loose bodies, and the size and extent of the osteophytes on the humerus and ulna (Fig. 76-5). Involvement of the radial head has been documented in about 85%.8 Bell and Minami et al2,31 have characterized the development of loose bodies as an integral feature of primary arthritis of the elbow. Special imaging studies are not needed and are of no value to diagnose this condition. A cubital tunnel view is sometimes obtained if the ulnar nerve shows signs of ulnar neuritis. These features do reflect the clinical expression and provide a guideline to treatment.

FIGURE 76-4 Anteroposterior roentgenogram of the elbow demonstrating ossification of the olecranon fossa.

TREATMENT

NONOPERATIVE TREATMENT

Symptomatic treatment is appropriate, especially in the early stages because symptoms are slowly progressive and well tolerated. Although anti-inflammatory agents may be of use, by the time the patient sees a surgeon, the clinical findings and functional limitations usually justify some intervention. This is in contrast with the experience of others in which nonoperative treatment appears appropriate and adequate.10 In addition to anti-inflammatory agents, in some instances a cortisone injection may be of value. One study, however, demonstrated that the use of hyaluronic acid was not effective in 18 patients treated with hyaluronic acid with the diagnosis of primary osteoarthritis of the elbow.54 The mean time to surgery from symptom onset is about 5 years. The most important feature of the initial treatment is to explain to the patient the cause of the pain and the natural history of the process, and to recommend activity modification. However, because this disorder is so often associated with one’s occupation, this advice usually goes unheeded or cannot be acted on. Avoiding pressure to the cubital tunnel is recommended if there are ulnar nerve symptoms.

OPERATIVE TREATMENT

Several surgical options exist and are evoked depending on the dominant symptoms and radiographic change (Table 76-1). For the most part, débridement by arthroscopy or by arthrotomy is the treatment of choice, with or without ulnar nerve decompression. In some instances, symptomatic loose bodies will be the primary pathology or at least the primary complaint. Under these circumstances, simple arthroscopic removal of the loose bodies relieves the patient of their symptoms5,44 and, in some instances, may even improve motion up to 15 degrees.44

TABLE 76-1 General Relationship of Major Symptoms with Preferred Treatment

| Dominant Symptom | Surgical Technique |

|---|---|

| Loose body | Arthroscopy |

| Extension loss | |

| Mild | Arthroscopy*/Column |

| Moderate | Column |

| Flexion loss | Column |

| Ulnohumeral arthroplasty | |

| Total elbow replacement | |

ARTHROSCOPY

Arthroscopic Management

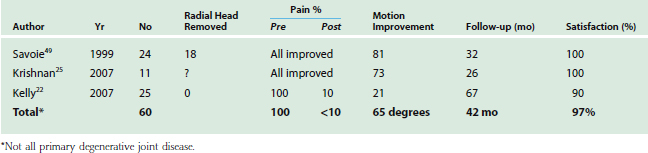

Arthroscopic débridement of the elbow is discussed in Chapters 38 to 40; however, there have been a number of reports specifically discussing arthroscopic débridement in the face of primary osteoarthritis (Fig. 76-6).16,23,28 These studies are summarized in Table 76-2. Although the sample is relatively small (60 patients) with a mean follow-up of just more than 3 years, it is impressive that more than 90% of patients expressed satisfaction with relief of pain and the improved arc of motion in these recent studies is greater than 60 degrees. Hence, arthroscopic débridement for primary osteoarthritis is emerging as a viable treatment option. In our opinion, the key elements to consider this option are

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree