Chapter 38 Primary Osteoarthritis of the Elbow

Introduction

Primary osteoarthritis of the elbow is a relatively uncommon condition mainly affecting middle-aged men. It is characterized by wear of the articular cartilage together with new bone formation at the joint surfaces.1 The condition is normally progressive, although the speed of progression is variable. In the general population it has a prevalence of between 1.3 and 2.0%,2,3 although Doherty and Preston working in a rheumatological clinic noted a prevalence of 7%.4

Background/aetiology

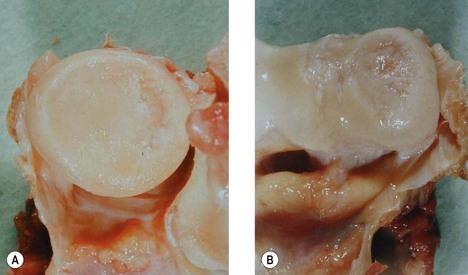

The natural history of articular cartilage changes within the elbow has been investigated by Goodfellow and Bullough.5 They examined 28 elbow joints retrieved at autopsy in subjects aged 18–88 years. They noted that with increasing age the radiocapitellar joint almost invariably showed degenerative change with a posteromedial radial head ulcer (Fig. 38.1A,B). Associated with this was an area of linear ulceration of the humeral crest between the trochlea and the capitellum. By contrast the cartilage of the ulnar-trochlear joint rarely showed evidence of degeneration. In older subjects grooves in the articular cartilage of this articulation were seen, although these did not expose the underlying bone. It was suggested that the differences in the pattern of wear between the radiocapitellar and ulnar-trochlear joints were related to the fact that the radiocapitellar joint has a combination of flexion, extension and rotational movements, whereas the ulnar-trochlear joint has only flexion and extension.

Murato et al6 noted similar changes in the elbow with ageing and concluded that there was a progression of change from normal ageing to the development of elbow osteoarthritis. They found that the degenerative change in the radiocapitellar joint was always more advanced than in the ulnar-trochlear joint.

Kashiwagi7 and Tsuge and Mizuseki8 noted erosion of the radial head with reciprocal loss of cartilage over the capitellum. Osteophytes occur around the radial head, but are predominantly seen at the tip of the olecranon and coronoid process. They may also be present around the olecranon and coronoid fossae.9 Osteophytes involving the medial aspect of the joint may also compress the ulnar nerve resulting in symptoms of ulnar neuritis. Bell10 first reported the presence of loose bodies within the elbow and Morrey11 has suggested that these occur in up to 50% of patients with elbow osteoarthritis. These loose bodies may be single or multiple and can be found in any compartment of the joint.

Thickening of the olecranon fossa membrane was originally noted by Kashiwagi7 when he performed the Outerbridge–Kashiwagi procedure. More recently a histological study has shown that the anterior and posterior cortices, together with the intramedullary bone of the olecranon fossa membrane, are all thickened in this condition.12

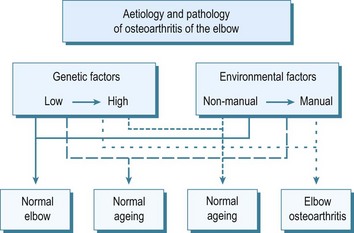

The aetiology of elbow osteoarthritis is not fully understood. Repetitive trauma is undoubtedly an important factor, but it is probable that other influences particularly genetic factors are also relevant in the development of this condition (Fig. 38.2).

Figure 38.2 Proposed interaction of genetic and environmental factors in the development of osteoarthritis of the elbow.

Holtzmann13 in a study of heavy manual workers suggested that the use of pneumatic tools might be an important predisposing influence. This view was supported by Rostock,14 who found that miners using pneumatic boring equipment experienced osteoarthritis of the elbow more commonly than shoulder or wrist osteoarthritis. Lawrence15 noted that 31% of miners using pneumatic drills for more than1 year developed elbow osteoarthritis compared with only 16% who had not drilled. Other authors, however, have failed to show an association with this type of work.16,17

Of greater significance was the finding from Lawrence’s study15 that in miners the elbow was the third most frequently affected joint with osteoarthritis after the spine and knee. Lawrence concluded that elbow osteoarthritis was a feature of all types of heavy manual work. More recently Stanley3 has shown a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of elbow osteoarthritis in men undertaking heavy manual work compared with those doing non-manual tasks (p = 0.016).

Presentation, investigations and treatment options

Clinical presentation

Investigations

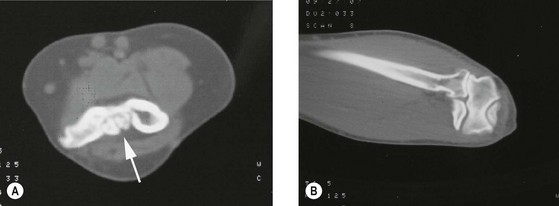

Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs are usually the only investigations required to make the diagnosis (Fig. 38.3). These usually show the characteristic features of the condition with osteophytes at the tip of the olecranon and coronoid process, narrowing of the radiocapitellar joint space, radial head osteophytes, loss of definition of the outline of the olecranon fossa due to thickening of the interfossa membrane and loose body formation.9 When multiple loose bodies are present, computed tomography allows confirmation of the number of loose bodies within the joint, together with the location and identifies the extent of osteophyte formation (Fig. 38.4).

Treatment options

It is obviously important that all patients are made aware of their diagnosis and that this is the cause of their symptoms. Those with minor complaints may find conservative management beneficial. The use of simple analgesics or non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs may relieve symptoms, and on occasion an intra-articular steroid injection can also be of benefit.4

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

Arthroscopic debridement

The arthroscopic treatment of osteoarthritis of the elbow is becoming increasingly popular. It is, however, dependent on the surgeon having a detailed anatomical knowledge of the elbow and appropriate arthroscopic expertise. These techniques have been used for the removal of loose bodies,18 debridement of osteophytes19 and for performing the ulnohumeral arthroplasty arthroscopically.20,21 The surgical set up and techniques available are beyond the remit of this chapter. For a more detailed description and discussion the reader is referred to Chapter 39.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree