Chapter 8 Preparation for Teaching in Clinical Settings

Nikos Kazantzakis in J. Canfield and M. V. Hansen’s A 3rd Serving of Chicken Soup for the Soul.1

After earning a Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) degree and completing 6 months of clinical practice, I was informed that I would need to serve as a clinical instructor (CI) for a physical therapist assistant (PTA) student who would be arriving in 1 week! I was comfortable with managing a full patient caseload and all related activities, including using the patient management approach to care and evidence-based practice, applying concepts of defensible documentation in electronic health records, integrating the International Classification of Functional Disability and Health (ICF) in physical therapy and patient management, participating in case and family conferences, conducting quality assurance review, establishing and seeking positive interprofessional relationships, contributing to translating evidence into practice by participating in a journal club and weekly in-services, directing and supervising PTAs and other support personnel, and attending monthly professional meetings. Now, without more than a simple proclamation or an orientation,2 I was to be assigned to a student for her first clinical education experience from a 2-year PTA program. Just when I was feeling like I finally had a handle on performing as a competent practitioner and meeting expectations, one more responsibility was “dumped” on me.

The first sketch is all too common in contemporary clinical education but illustrates a situation that can be prevented or eliminated given adequate training and resources. The second scenario is an emerging situation in physical therapy clinical education and describes new challenges confronting both experienced and novice clinical educators as a result of changes in doctoral professional education, lengthening3 of clinical education experiences, exploration of different models of clinical supervision, and constraints related to patient reimbursement with students involved in the care. For both case situations, information provided in this chapter assists novice and experienced clinical educators with information and resources about the clinical education milieu; the roles and responsibilities of faculty, clinicians, and students involved in clinical education; preparation to be a successful clinical teacher; and alternative models and supervisory approaches for the delivery of clinical education.

After reading this chapter, the reader will be able to:

1. Understand the complexities of and relationships between different contextual frameworks in which students’ academic and clinical learning occur.

2. Recognize the dynamic organizational structure of clinical education and the roles and responsibilities of persons functioning within this structure, including components of effective academic and clinical education partnerships.

3. Define the preferred attributes of clinical educators that contribute to enhanced student learning.

4. Identify hallmarks of quality clinical educator/preceptor/supervisor development training programs to facilitate planning, implementing, and evaluating clinical education programs and student learning.

5. Describe alternative clinical education models, supervisory approaches, and cooperative and collaborative approaches to providing student supervision and their relative strengths, considerations and limitations.

Physical therapy education

Imagine education for physical therapists and PTAs occurring solely in an academic milieu or without any student clinical practice as an integral part of the educational process. Since the profession’s inception, clinical practice as part of the curriculum has always been and continues to be of paramount importance and at the heart of students’ educational experiences. Of significance is clinical practice’s role in students’ progression through the curriculum in preparation for entering practice. This is achieved by bridging the worlds of theory and practice, teaching in a real-world laboratory lessons that can only be learned through practice, introducing students to the peculiarities of the practice environment and the profession, and refining knowledge, psychomotor skills, and professional behaviors by managing patients with progressively more complex pathologies.4 This aspect of the physical therapy professional curriculum is known as clinical education. On the one hand, clinical education is not currently constrained by type of practice setting or its geographical location, diversity of persons capable of serving as clinical educators, or the patient populations that clinical educators serve.5–7 Strohschein and colleagues8 believe, however, that the current climate of health care, with growing fiscal and time constraints, creates a growing tension between provision of appropriate patient care and provision of clinical education experiences for students. On the other hand, clinical educators are powerful role models for students during their professional education and significantly influence where, how, and with whom students choose to practice after graduation, and whether they choose to become future clinical educators.9–11 Yet, in 2003 qualifications and credentials of supervising physical therapists in the United States were reported as quite varied, with the typical CI being female with a highest earned baccalaureate degree, more than 5 years of clinical practice, and 4 years of clinical teaching and has supervised two students in a 12-month period. Likewise, it was reported that the typical CI is not a member of the APTA and is neither APTA Credentialed nor a board-certified clinical specialist.12 Thus, the outcome of physical therapy education is, in part, a reflection of the quality of clinical educators who help prepare graduates to deliver quality, cost-effective, and evidenced-based services to meet the needs and demands of society within an ever-changing health care environment.

Differences between academic and clinical education

The greatest fundamental difference between academic education and clinical education lies in their service orientations. Physical therapy academic education, situated within higher education, exists for the primary purpose of educating students to attain core knowledge, skills, and behaviors. In contrast, clinical education, situated within the practice environment, exists first and foremost to provide cost-effective and high-quality care and education for patients, clients, their families, and their caregivers. Academic faculties are remunerated for their teaching, scholarship, and community and professional services. Clinical educators are compensated for their services as practitioners by rendering patient and client care and related activities. In most cases, unless as a function of experience or as an employee of an academic institution, clinical educators receive little or no direct financial compensation for teaching students.13 Physical therapy clinical educators are placed in a precarious position of trying to effectively balance and respond to two “masters.” The first master, the practice setting, requires the practitioner to deliver evidenced-based, cost-effective, and high-quality patient services. The second master, higher education, wants the clinical educator to respond to the needs of the student learner and the educational outcomes of the academic program.

Other differences between physical therapy clinical education and academic education relate to the design of the learning experience. Educating students in higher education most often occurs in a predictable classroom environment that is characterized by a beginning and ending of the learning session and a method (written, oral, practical/simulated demonstration) of assessing the student’s readiness for clinical practice. Student instruction can be provided in numerous formats with varying degrees of structure, including lecture augmented by the use of a variety of technologies, laboratory practice, discussion seminars, collaborative peer activities, tutorials, problem-based case discussions, computer-based instruction and patient simulations, and independent or group work practicums. With advancements in technology, including distance education, hypermedia, virtual reality, and telehealth, contemporary teaching-learning archetype is being redesigned, and alternative structures and systems for classroom learning are clearly evolving.14,15

In contrast, the clinical classroom by its very nature is dynamic and flexible. It is an unpredictable learning laboratory that is constrained by time only as it relates to the length of a patient’s visit or the workday schedule. Sometimes, to an observer, delivery of patient care and educating students in the practice environment may seem analogous in that they appear unstructured and even chaotic. Remarkably, student learning continues with or without patients and is not constrained by walls or by location (e.g., community-based services, service learning opportunities, international experiences, or home visits). Learning is not measured by written examination, but rather is assessed based on the quality, efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and outcomes of patient and client care provided by a student when measured against a standard of clinical performance.15–17 Resources available to the clinical teacher may include many of those used by academic faculty, such as instruction using technology, practice on a fellow student or the clinical educator, online education or discussion, analysis of a journal article using principles of evidence-based practice,18 or engaging in a teachable learning moment to enhance learning and foster intellectual curiosity.19 Additional resources available to the clinical educator include collaborative and mentored student learning within and between professions, online libraries of patient cases, coaching strategies to more effectively manage clinical decisions, in-service education, grand rounds, surgery observation, special clinics and screenings (e.g., seating clinic, fitness screenings, community-based education to prevent common falls in the elderly population), presurgical examinations, on-site and online continuing education course offerings, interactions with other health professionals, and participation in clinical research. Rich learning opportunities are available in practice that complement, clarify, and augment much of what is provided in physical therapy academic education.20

Because learning occurs within the context of practice and patient care, the clinical teacher must be characterized as more of “a guide by the side” rather than the “sage on stage” that characterizes the classroom educator.21 The clinical teacher, primarily through interactions, teaching, and handling of patients, assumes multiple roles, including facilitator, coach, supervisor, role model, mentor, and performance evaluator.15 The clinical educator provides opportunities for students to experience safe practice. She or he asks strategically sequenced probing questions22 that encourage learners to reflect, reinforces students’ thinking and clinical decision making, fosters scholarly inquiry and sorting fact from fiction, and, by example, teaches and models for students how to manage ambiguities (e.g., balancing functional and psychosocial needs of the patient with available third-party payment for services).21,23,24

In summary, higher education and health care environments differ in relation to student learning because educators in each assume distinct roles and responsibilities that are circumscribed by the context in which learning occurs and the primary customer being served. Despite these differences, it is imperative that the two systems frequently communicate and interact with each other to fulfill the curricular outcomes of physical therapy programs and to ensure greater congruence between the theoretical, practical, and translational aspects of practice. In fact, academic and clinical educators, as partners in collaboration, must make concerted efforts to consciously bridge their differences given ongoing changes in health care and higher education that exist in different organizational structures. It is incumbent on the stakeholders in both communities to take the time to understand how these systems currently function and could function in the future. Thus, academic and clinical communities must explore new and innovative collaborative partnerships and organizational structures that enable quality learning experiences to continue in clinical practice in order to prepare safe, competent, and effective clinicians to meet the needs and demands of society.8,25

Relationship between clinical and academic education

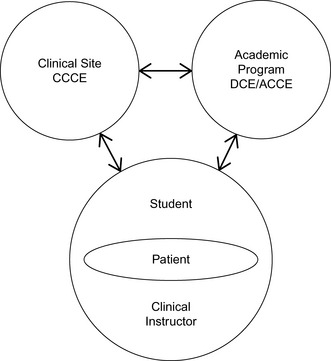

The organization of clinical education is designed to provide a mechanism for academic faculty to share with clinical faculty their respective curricula and student expectations. In return, clinical faculty inform academic faculty of the relevance of the academic curriculum to entry-level practice and the ability of students to transform knowledge and theory into practice with patients as evidenced by their clinical performance.26 Excluding students, the organizational system is often designed with persons providing three essential positions within clinical education. Persons assuming these roles must continually interact to ensure the provision of quality physical therapy education for students. These three roles are most commonly titled the Director of Clinical Education (DCE) or Academic Coordinator of Clinical Education (ACCE), the center coordinator of clinical education (CCCE), and the clinical instructor (CI). The DCE/ACCE is situated in the academy, whereas the CCCE and CI are based in clinical practice. Although, often not discussed as a part of the relationship between academic and clinical education, at the core of the clinical experience, first and foremost, is the patient (Figure 8-1).

Although the three primary players and the students largely manage physical therapy clinical education, it is important to remember that it is every physical therapist and PTA educator’s responsibility to be vested in clinical education. Full-time clinical education represents a mean of 29.6% of the total curriculum3 and is characterized as that part of the academic experience that allows students to apply theory and didactic knowledge to the real world of clinical practice.3 As such, all academic faculty contribute to the effectiveness of the clinical learning experience because students’ performance in the clinic is a direct reflection of how they were educated by faculty during the didactic portion of the curriculum. Faculty seek to understand how their classroom experiences relate to student performance in the clinic, and clinicians must comprehend how and what information presented in the classroom relates to the clinical education process and entry-level performance expectations. This is accomplished in a variety of ways, including faculty making clinical site visits and phone calls using established guidelines27; facilitating continuing education, external funding, and clinical research in collaboration with clinicians; and serving as clinical educators in a self-contained model of clinical education.28 Decisions about student clinical competence should not rest solely with the DCE/ACCE, but should reflect the collective wisdom of academic and clinical faculty assessments,29,30 student self-assessments, consumers,31 and employer assessments.32 Additionally, the academic program has a responsibility to visibly demonstrate its commitment to clinical education by actively involving clinical educators in relevant aspects of curriculum design and development, including models of clinical education, implementation, and assessment of the physical therapy program.

Clinical education roles and responsibilities

Roles and responsibilities of students

The true messengers in clinical education are students. Students provide feedback to all stakeholders involved in the clinical education system. Given the various alternative models and supervisory approaches for providing clinical education, students bear a heavy burden because learning experiences are provided based on information received from academic programs that may be incomplete in relation to individual student learning needs. Only students can articulate their needs to the CI on a daily basis; therefore, they must take responsibility for their active learning if they wish to maximize their time in the practice setting.33 Students must actively engage in the decision-making process of clinical site selection.34,35 Interestingly, Gangaway and Stancanelli’s 200736 study of students’ perceptions of factors that were important for site selection determined that financial considerations, type of specialty offered by the facility, fulfilling program requirements, and reputation of the facility were found to be statistically more important than travel, proximity to school, and free or low-cost housing provided by the facility.

Integral to the site selection process is the need for ongoing student self-assessment and reflection, which identify the student’s knowledge and performance strengths, deficiencies, and inconsistencies.23 As part of this responsibility, students must feel comfortable providing constructive feedback to academic and clinical faculty. Faculty must remain open and flexible to student needs and be willing to modify the curriculum when revisions are shown to be necessary and feasible.

Self-accountability for behavior and actions is critically important for students as part of their learning contract. However, faculty should guide and model appropriate professional behavior and be willing to confront areas in which the students’ professional values and behaviors are considered inappropriate or problematic.37–39

Roles and responsibilities of the director/academic coordinator of clinical education

Since 1982, the roles, responsibilities, and career issues of the DCE/ACCE in physical therapy education have been investigated and discussed by several authors.40–45 Although these studies span more than two decades, the essential responsibilities assumed by the DCE/ACCE have remained fairly consistent as related to administration and management, teaching, and service.43,44 Additional skills that are incorporated in the role of the DCE/ACCE include increased use and application of technology for the purpose of communication, networking, and enhanced administrative efficiency and effectiveness, including the use of a clinical education consortia e-community, Web-based Clinical Site Information Form,46 Web-based Physical Therapist Clinical Performance Instrument,47 and Physical Therapist Assistant Clinical Performance Instrument,48 use of more consistent student clinical performance assessment instruments that glean program and clinical education data49 to manage and direct the clinical education program (including budget, personnel, affiliation agreements50 and resources), assumption of leadership within clinical education, and other collaborative initiatives in working with program consortia, professional association groups, other health professions, and global clinical education opportunities including international clinical site placements.51

The DCE/ACCE functions in a pivotal faculty role in physical therapy education. She or he serves as the liaison between the didactic and clinical components of the program. In some programs, because of the number of students and the resultant number of clinical education sites required, more than one person has shared DCE/ACCE responsibilities (as co-ACCEs or as DCE/ACCE and assistant ACCE). The DCE/ACCE of a physical therapist program is a core faculty member and a licensed physical therapist with an understanding of contemporary physical therapist practice, quality clinical education, the clinical community, and the health care delivery system. Specific expectations of the DCE/ACCE based on their roles and responsibilities are articulated in the Evaluative Criteria for the Accreditation of Physical Therapist Programs.6

Additionally, the DCE/ACCE in a physical therapist program preferably has an earned DPT or doctoral degree or desire to pursue doctoral studies, has academic responsibilities including teaching, engages in scholarship, and provides community and professional service while balancing the many other unique administrative responsibilities associated with the position.52 In 2010-2011, the highest degrees reported for DCEs/ACCEs were 12.8% PhD, 27.2% DPT degree, 34.3% postprofessional masters, and 11.6% bachelors.3 The DCE/ACCE of a PTA program should be either a PTA or physical therapist with an earned bachelor degree or desire to pursue undergraduate studies. Additional preferred requirements include prior teaching experience; knowledge of education, management, and adult learning theories and principles; active involvement in clinical practice and professional activities at local, state, or national levels; and earned status as an APTA Credentialed Clinical Instructor.53 The roles and associated responsibilities of a physical therapist program DCE/ACCE43–45,52 are found in Table 8-1.

Table 8-1 Roles and Responsibilities of the Director of Clinical Education/Academic Coordinator of Clinical Education

| Primary Roles of the DCE/ACCE | Responsibilities Associated with Each Role |

|---|---|

| Communication between the academic institution and affiliated clinical education sites | Provide clinical sites with current program information (i.e., program philosophy, policy and procedures, clinical education agreements, clinical placement requests, student clinical assignments, required information for accreditation, performance assessments, and federal and state regulations that affect patient care provided by students). Foster ongoing and reciprocal communication between academic and clinical faculty and students through various mediums (e.g., phone, written, electronic and web-based correspondence, on-site visitations). |

| Clinical education program planning, implementation, and assessment | Perform academic and administrative responsibilities consistent with the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE), federal and state regulations, institutional policy, and practice setting requirements. Coordinate and teach students about clinical education and related content, including the need to actively participate in the outcome of their clinical learning experiences. Remain current regarding issues in health care delivery and higher education that affect the provision of clinical education. Coordinate, monitor, and assess the clinical placement of students. Develop, maintain, and administer information and education technology systems that support clinical education and the curriculum. Coordinate, facilitate, and evaluate clinical education in the academic program, including instruments used for evaluation of the clinical education component of the curriculum for purposes of curricular assessment and revisions.6,7,41–45,54 Review student clinical performance evaluations and provide feedback and interventions as required. Determine, in collaboration with program faculty, whether students have successfully met explicit learning objectives for the clinical experience to enable continued progression through the curriculum. |

| Clinical education site development | Develop criteria and procedures for maintaining quality clinical sites committed. Develop and maintain an adequate number of clinical education sites relative to quality, quantity, and diversity of learning experiences (e.g., continuum of care, life span, commonly seen patient diagnoses) to meet the educational needs of students and the academic program. |

| Clinical faculty development | Assess the faculty development needs of clinical educators. Develop, provide, and assess clinical faculty development programs that educate and empower clinical educators to effectively fulfill their roles as clinical teachers.43–45,54 |

Adapted from Department of Education. American Physical Therapy Association Model Position Description for the Academic Coordinator for Clinical Education/Director of Clinical Education. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association, February 2011.

Additional activities that the DCE/ACCE should be involved with include the following43–45,54:

• Consortia activities (e.g., a group of regional academic programs and clinical educators that sponsor collaborative initiatives)

• Accreditation-related activities

• Program curriculum and university-based committee activities

• Management of budget related to clinical education

• Coordination of clinical education advisory committees

• State, regional, and national professional activities related to clinical education

• Leadership roles in bridging and strengthening academic-clinical partnerships in designing models for delivering clinical education

Given the unique responsibilities associated with this position in higher education and the ongoing need for clinical education program assessment, faculty performance assessment for the DCE/ACCE in support of this position is useful. There are several assessment tools available that define specific performance expectations for the DCE/ACCE. These tools are based on a 360-degree assessment of these performance expectations by program directors, academic faculty, students, CCCEs, CIs, and the DCE/ACCE. Assessments for the DCE/ACCE are beneficial to provide information about the DCE/ACCE’s performance, describe workload responsibilities for those aspects associated with faculty and that are unique to this position, identify areas for professional growth and development, and provide constructive feedback about the clinical education program.44,45,54

In 1988, Deusinger and Rose55 challenged ACCEs to reexamine their role as part of physical therapy education by saying, “Like the dinosaur, the position of the ACCE is certain to become extinct in physical therapy education. The viability of this position is threatened because of the present preoccupation with administrative logistics and student counseling, a preoccupation that prohibits full participation as an academic physical therapist.” They go on to suggest that “the role of the ACCE must be redefined for this faculty member to survive the demands of academia and serve the needs of the profession.”55 They expressed the hope that ACCEs would not become extinct in this position but instead would be transformed and emerge as an equal, valued, and respected member of the academic community. Twenty-three years later, the DCE/ACCE position still functions as a critical member of physical therapy core faculty with more well-defined roles and responsibilities that have expanded over the years. Today there are more doctoral-prepared DCEs/ACCEs with earned tenure (12.8%) or in tenure-eligible lines (14.3%). A majority hold the rank of assistant professor (50.6%), associate professor (18.1%), or full professor (1.6%). For those not with tenure, 40.3% of the DCEs/ACCEs are on a clinical track, and 32.6% are not eligible for tenure at their institution.3

Roles and responsibilities of the center coordinator of clinical education

The CCCE’s primary role is to serve as a liaison between the clinical site and the academic institutions. From the student’s perspective, the CCCE serves in a unique but critical capacity. The CCCE is viewed as the neutral party at the clinical site who functions in the role of active listener, problem solver, conflict manager, and negotiator when differences occur between a student’s perception of her or his performance and the CIs perception of the performance. In some situations, CCCEs function as mentors for individuals serving as CIs or those potentially interested in becoming CIs.5

Because of current pressure in health care settings to maximize human resources, it is as likely that the CCCE may be a physical therapist or PTA as it is that the individual may be a non–physical therapy professional (e.g., occupational therapist or speech therapist). In some professions, the use of a CCCE has facilitated the ability to assist in situations where there was an undersupply of clinical placements.56 Whether the CCCE is a physical therapist or PTA or another health care professional, the following characteristics and qualities are considered universal to the role:

1. Interest in students and commitment to providing quality learning experiences

2. Experience in providing clinical education to students in the respective professions

3. Effective interpersonal communication and organizational skills

4. Knowledge of the clinical education site and its resources

5. Experience serving as a consultant in the evaluation process of students

6. Knowledge of professional ethics and legal behaviors

7. Knowledge of contemporary issues in clinical practice and the clinical education program, educational theory, and issues in health care delivery5

If the CCCE is a physical therapist or PTA, it is expected that he or she will possess attributes commensurate with that of CIs (see CCCE role responsibilities in the following list). CCCEs can assess their capabilities and competence by completing the APTA self-assessment for CCCEs.5

• Obtaining administrative support to develop a clinical education program by providing clinical education site administrators with sound rationale for development

• Determining clinical site readiness to accept students

• Contacting academic programs to determine whether the clinical site’s clinical education philosophy and mission is congruent with that of the academic program

• Completing the necessary documentation to become an affiliated clinical education program (e.g., negotiated legal contracts that define the roles and responsibilities of the clinical site and the academic institution; clinical site information form [CSIF],20 that documents essential information about the clinical site, personnel, and available student learning experiences made available in a web-based format in 201146,47; policy and procedure manuals frequently available in an online format for ease of maintaining currency; and, in some cases, self-assessments for the clinical education site, the CI, and the CCCE5). The CCCE ensures that all required documentation is completed accurately and in a timely manner and is periodically updated as warranted by changes in personnel and the clinical site.5 To assist the CCCE in managing his or her responsibilities, a Reference Manual for Center Coordinators of Clinical Education57 was created that address administrative, managerial, supervisory, communication, and assessment components of this position.

• Coordinating the CI student assignments and assessing the availability of learning experiences for students at the clinical site

• Responding to inquiries by academic program for available student placements and scheduling the number of students that can be reasonably accommodated by the clinical site on an annual basis

• Developing guidelines to determine when physical therapists and PTAs are competent to serve as CIs for students

• Providing mechanisms whereby CIs can receive the necessary orientation2 and training to provide quality student clinical instruction

• Reviewing student clinical performance assessments to ensure their accuracy and timely completion

• Understanding legal risks,58,59 including the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA),60,61 Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA),62 and provisions associated with teaching and supervising students in the clinic

The role of the CCCE has changed over time given the milieu in which contemporary physical therapy clinical education occurs. Because of health care reform and resulting cost-containment measures that have occurred throughout the health care system, the CCCE may be a coordinator who manages administrative responsibilities associated with clinical education in large multicenter facilities, may be a physical therapist or PTA who can function as a mentor for new CIs, or may be a non–physical therapist or PTA who functions solely as an administrator without the expectations or necessary qualifications to mentor CIs or students, or the facility may not have a CCCE. It is critical that the profession continues to provide high-quality professional development programs that continue to educate the next generations of clinical teachers and mentors capable of ensuring the future quality and effectiveness of physical therapy services.63

Roles and responsibilities of the clinical instructor

The CI is involved with the daily responsibility and direct provision of student clinical learning experiences. Central to every clinical learning experience is the student-CI-patient relationship. Often, students perceive that the success or failure of the clinical learning experience can be attributed solely to the CI. In reality, the quality of the learning experience is dependent on the interaction, management, and relationship of the learning triad of the CI, patient, and the student along with the community or environment in which learning occurs.64 In physical therapy, the student supervisor is best known as the clinical instructor. Other synonyms for the CI include clinical tutor, clinical supervisor, clinical preceptor, clinical teacher, clinical mentor, and clinical educator. Each of these labels can be identified with one or more roles that this individual routinely performs. Much has been written in the health care literature about the CI’s role, responsibilities, attributes of the CI that enhance student learning, and student and teacher perceptions of clinical instructor effectiveness.12,37–39,65–72

Skills and Qualifications of a Successful Clinical Instructor

CIs’ roles are multifaceted and encompass varied and diverse behaviors that include facilitating, supervising, coaching, guiding, consulting, teaching, evaluating, counseling, advising, career planning, role modeling, mentoring, and socializing. Before serving as a CI for students in physical therapy, competence should be demonstrated by the CI in several performance dimensions5:

• Clinical competence evidenced through the use of a systematic approach to care using the patient management model (i.e., examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, intervention, outcomes),73–75 critical thinking skills, and effective time management skills

• Adherence to legal practice standards58,59 and demonstration of ethical behavior76–82 that meets or exceeds the expectations of members of the profession of physical therapy

• Effective communication skills, including the ability to provide feedback to students, demonstrate skill in active listening, and initiate communication that may be difficult or confrontational67–70

• Effective behavior, conduct, and interpersonal relationships with patients/clients, students, colleagues, and other health care providers82,83

• Effective instructional skills, including organizing, facilitating, implementing, and evaluating planned and unplanned learning experiences that take into consideration student learning needs, level of performance within the curriculum, goals of the clinical education experience, and the available facility resources

• Effective supervisory skills that include clarifying goals and student performance expectations, providing timely formal and informal feedback, making periodic adjustments to structured learning experiences, performing constructive and cumulative evaluations of student performance, and fostering reflective practice skills84

• Effective performance evaluation skills to determine professional competence,38,39,71,85,86 ineffective or unsafe practices,83,84 constructive remedial activities to address specific performance deficits, challenging activities to engage exemplary performers, and the ability to engage students in ongoing self-assessment

Individuals can evaluate their readiness for or competence in serving as a CI by completing the self-assessment for CIs.5 Higgs and McAlister87 in their research identified six dimensions of a CI (Box 8-1). Different than competencies or a set of CI skills, these dimensions are oriented toward the CIs’ socialization to their role and perception of themselves in the capacity of a CI.

Box 8-1 Six Dimensions of a Clinical Instructor

2. Having a sense of relationship with others as a central feature of clinical education

3. Having a sense of being a clinical educator

5. Seeking dynamic self-congruence

From Higgs J, McAllister L. Being a clinical educator. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract 2007;12:187-200.

In March 2010, a document entitled Physical Therapist Clinical Education Principles88 was adopted by the APTA Board of Directors as a voluntary resource for physical therapist academic and clinical educators. Through a widespread consensus-based process and the involvement of multiple stakeholders, new graduate and CI performance outcomes were defined in this document. For the CI, 16 performance outcome categories were defined that increased the overall number and in some cases level of CI expected performance (Box 8-2).