Abstract

Objectives

The pre-return-to-work medical consultation during sick leave for low back pain (LBP) aims at assessing the worker’s ability to resume working without risk for his/her health, and anticipating any difficulties inherent to returning to work and job retention. This article summarizes the good practices guidelines proposed by the French Society of Occupational Medicine (SFMT) and the French National Health Authority (HAS), and published in October 2013.

Methods

Good practices guidelines developed by a multidisciplinary and independent task force (24 experts) and peer review committee (50 experts) based on a literature review from 1990 to 2012, according to the HAS methodology.

Results

According to the labour regulations, workers can request a medical consultation with their occupational physician at any time. The pre-return-to-work consultation precedes the effective return-to-work and can be requested by the employee regardless of their sick leave duration. It must be scheduled early enough to: (i) deliver reassuring information regarding risks to the lower back and managing LBP; (ii) evaluate prognostic factors of chronicity and prolonged disability in relations to LBP and its physical, social and occupational consequences in order to implement the necessary conditions for returning to work; (iii) support and promote staying at work by taking into account all medical, social and occupational aspects of the situation and ensure proper coordination between the different actors.

Conclusion

A better understanding of the pre-return-to-work consultation would improve collaboration and coordination of actions to facilitate resuming work and job retention for patients with LBP.

1

Introduction

Even though most workers recover completely after an episode of back pain, 2 to 7% can develop chronic low back pain (LBP) with subsequent long-term sick leave . This can have a great impact on the career path of those workers and lead to major socioeconomic consequences .

Following a long-term sick leave, the employee can request to his/her occupational physician (OP), a pre-return-to-work (RTW) medical consultation when still on sick leave. This consultation can also be programmed at the initiative of the worker’s general practitioner or the Social Security advising physician. The pre-RTW consultation is a worker’s right as indicated in the French labor law texts (Art. R4624-20 and 21 of the labour regulation). It is a free consultation, with the OP, regardless of the sick leave duration; it can be renewed as many times as needed upon the simple request of the employee. Contrarily to the RTW consultation, at the time of the pre-RTW consultation the physician does not have to deliver an aptitude or non-aptitude certificate, but rather its goal is to engage in a communication with the worker’s organization, in agreement with the employee, in order to implement the necessary conditions for returning to work.

The objective of the pre-RTW consultation, following sick leave for LBP, is to evaluate the ability of the employees to resume their former job, without any risks for their health, according to their symptoms and their social and occupational situation (Art. R4624-21 labour regulation). The pre-RTW consultation is a privileged time to talk with the workers regarding the difficulties they anticipate when returning to work and explore with them the possible options. This consultation helps identify the necessary accommodations to the workstation and work schedule (therapeutic part-time return-to-work) to be implemented in partnership with the worker’s employer, and remind workers of prevention measures.

The legal frameworks of the medical and occupational follow-up by the OP concerns employers, employees, but also their referent primary care physicians and specialists. A better knowledge of the legal features related to this issue is necessary to promote an improved partnership between care physicians (primary care physician or specialists) and the occupational physician, especially, via the pre-RTW consultation performed by the OP.

This article proposes a synthesis of the literature and the first good practices recommendations on the pre-RTW consultation for LBP employees, proposed by the French Society of Occupational Medicine (SFMT) and the French National Health Authority (HAS), in October 2013 . Even though these good practices recommendations are first of all aimed at occupational physicians, they are also valuable for primary care physicians and specialists caring for LBP patients, as well as the other medical and medico-social actors and company representatives involved in sustainable job retention and work disability prevention.

2

Methods

These GPRs were elaborated according to the “Clinical practice recommendations” proposed by the French National Health Authority .

The GPRs were elaborated by a workgroup and revised by a reading group of 50 experts, after 10 meetings of the work group between April 2012 and May 2013. The workgroup was multidisciplinary and associated different professionals; participants had a good knowledge of professional practices in the domain corresponding to the theme of the recommendations and were able to assess the relevance of the studies published and the various clinical situations evaluated. The independence and objectivity of the experts about the topic of the recommendations were verified via the conflict of interests disclosure forms that each expert sent to the HAS . No direct or indirect conflict of interest in relation to the topics of these recommendations was evidenced.

A systematic review of the literature between January 1990 to March 2012 was conducted in several databases (PubMed, Embase, NIOSHtic-2 and Cochrane Library), websites, institutional reports and documents of the main international organizations in charge of work-related healthcare. The keywords used were (low back pain or backache or sciatica) and (occupational health or occupational medicine or occupational disease or occupational accident) and (interventions or prevention or return-to-work or absenteeism or sick leave or disability or retirement or job retention or employment or job change or job adaptation or job loss or ergonomics or rehabilitation or back school).

Based on the data yielded by the literature and advice from professionals in the workgroup, the level of evidence of the proposed recommendations was graded according to the following levels :

- •

grade A – validated scientific evidence: based on studies with a high level of evidence: randomized controlled vs placebo clinical trials with high statistical power and without major bias or meta-analysis of randomized comparative clinical trials, decision analysis based on well-conducted studies;

- •

grade B – scientific presumption: based on scientific presumption using studies with intermediate level of evidence, such as randomized comparative trials with low statistical power, well-conducted non-randomized comparative trials, cohort studies;

- •

grade C – low level of scientific evidence: based on studies with a lower level of evidence, such as case studies, retrospective studies, series of cases, comparative studies with major biases.

- •

grade AE – scientific expert agreement: in the absence of studies, recommendations have been based on experts’ opinions resulting from a workgroup, after having consulted a reading group. The absence of level of evidence grade does not mean that the recommendations are not relevant and useful. It must, however, encourage teams to conduct further studies.

2

Methods

These GPRs were elaborated according to the “Clinical practice recommendations” proposed by the French National Health Authority .

The GPRs were elaborated by a workgroup and revised by a reading group of 50 experts, after 10 meetings of the work group between April 2012 and May 2013. The workgroup was multidisciplinary and associated different professionals; participants had a good knowledge of professional practices in the domain corresponding to the theme of the recommendations and were able to assess the relevance of the studies published and the various clinical situations evaluated. The independence and objectivity of the experts about the topic of the recommendations were verified via the conflict of interests disclosure forms that each expert sent to the HAS . No direct or indirect conflict of interest in relation to the topics of these recommendations was evidenced.

A systematic review of the literature between January 1990 to March 2012 was conducted in several databases (PubMed, Embase, NIOSHtic-2 and Cochrane Library), websites, institutional reports and documents of the main international organizations in charge of work-related healthcare. The keywords used were (low back pain or backache or sciatica) and (occupational health or occupational medicine or occupational disease or occupational accident) and (interventions or prevention or return-to-work or absenteeism or sick leave or disability or retirement or job retention or employment or job change or job adaptation or job loss or ergonomics or rehabilitation or back school).

Based on the data yielded by the literature and advice from professionals in the workgroup, the level of evidence of the proposed recommendations was graded according to the following levels :

- •

grade A – validated scientific evidence: based on studies with a high level of evidence: randomized controlled vs placebo clinical trials with high statistical power and without major bias or meta-analysis of randomized comparative clinical trials, decision analysis based on well-conducted studies;

- •

grade B – scientific presumption: based on scientific presumption using studies with intermediate level of evidence, such as randomized comparative trials with low statistical power, well-conducted non-randomized comparative trials, cohort studies;

- •

grade C – low level of scientific evidence: based on studies with a lower level of evidence, such as case studies, retrospective studies, series of cases, comparative studies with major biases.

- •

grade AE – scientific expert agreement: in the absence of studies, recommendations have been based on experts’ opinions resulting from a workgroup, after having consulted a reading group. The absence of level of evidence grade does not mean that the recommendations are not relevant and useful. It must, however, encourage teams to conduct further studies.

3

Results

3.1

Information and advice to workers with LBP

Foremost, “it is recommended to ensure that workers with LBP, a long sick leave or repeated sick leaves, have been informed of the possibility of benefiting from one or more pre-RTW consultations (Grade AE)”.

Common LBP is a pathological model where individual and social representations (“fears” and “beliefs”) of pain play an important role in the genesis of functional impairments and the progression to chronicity . The clinical examination is the ideal time to give workers precious information regarding the LBP diagnosis, care management and prognosis. This conversation with the physician can, in itself, have a therapeutic impact since the physician addresses the dysfunctional representations or “false beliefs”, which can then be identified and modified. It can also help restore confidence in workers who were given contradictory information or medical advice . Thus, “it is recommended to deliver information on LBP risk and LBP pathology since it improves knowledge and helps positively change representations (‘fears and beliefs’) and maladaptive behaviors (movement avoidance) related to LBP (Grade B)”.

3.1.1

Information modalities

“Prevention actors, such as healthcare professionals, must be aware of the influence that their own representations (or ‘beliefs’) can have on the content of the message they are delivering to the patient or worker (Grade B)”. In fact, healthcare professionals must keep in mind that their own “beliefs” are regularly associated to those of their patients , and that over-medicalized and high profile care management can have real deleterious effects, and that the attitude of physicians towards LBP patients, can be in itself, a factor promoting the progression to chronicity . “It is also recommended to ensure the coherence of messages delivered to patients, because of the deleterious nature of discordant speeches, and to ensure that the worker fully understands the essential messages (Grade AE)”. As a matter of fact the information given to the employee can be a double-edged sword since divergent or poor quality messages can negatively impact the well-being of the LBP patient and delay the return to normal life activities and work . “If possible, the oral message will be supported by written information in accordance with the latest guidelines (for example, the ‘back book’ (Grade A)” since the message becomes more effective when coupled with a written document underlining similar information . Furthermore, using a booklet increases the level of knowledge and satisfaction of patients, as well as their confidence and compliance to the recommendations .

3.1.2

Information content

“The goal is to deliver essential, coherent and accessible information (Grade A”; i.e. delivered in a comprehensible and everyday language adapted to patients and their status. The information should be limited to a restricted number (3 to 5) of clear messages . “The content of the message must remind the subject that the onset of LBP is due to multiple factors and that occupational factors are one of the modifiable factors that can impact LBP incidence (Grade B)”.

“The information must be reassuring regarding the prognosis (Grade AE), reminding people that LBP is common and frequently recurrent, but that LBP episodes are usually short-termed with spontaneous positive resolution (Grade B)”. A high level of dysfunctional “fears and beliefs” and anxiety might require more explanation time to reassure workers on the prognosis .

“The information should explain and downplay the technical and medical terms, because of the absence of anatomical-clinical similarity for common LBP (Grade AE)”.

“It is also recommended to encourage worker to continue or resume physical activities, and if possible, returning to work taking into account the characteristics of the job context and the possibilities of job accommodations (Grade A)”. In fact, it is important to underline that long-term rest can promote chronicity and slow down the rehabilitation and that conversely, staying active, continuing normal activities, decreases chronic impairments and the risk of recurrence while promoting an earlier RTW .

Finally, the pre-RTW is the ideal time to “update the information and heighten awareness on basic principles for preventing occupational risks (Grade AE)”.

3.2

Prognostic evaluation of LBP workers

“It is recommended to replace the LBP episode in the medical and occupational history of the person, looking specifically for changes in job conditions and thus ensuring that the OP has the complete up-to-date data on the job context (Grade AE). It is also recommended to evaluate the impact of LBP on the occupational situation and appreciate with patients the risks to their health, taking into account the risk assessment of the particular job situation, potential accommodations and medical, social and occupational context (Grade AE); in order to determine, in partnership with the worker, the need for job situation/job accommodations and/or medical restrictions or referring the worker to his/her primary care physician and/or change the medical and occupational follow-up by the OP (Grade AE)”.

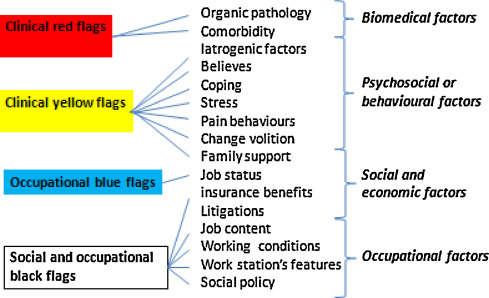

The purely biomedical model is insufficient to explain the complexity of persistent LBP. Thus, some so-called “psychosocial” factors seem to be frequently associated with LBP progressing to chronicity . Furthermore, individual, occupational and organizational factors influence the risk of progressing towards long-term incapacity and never returning to work. This is why, in case of persistent or recurrent LBP in a worker on long-term sick leave or going on repeated sick leaves, “it is recommended to evaluate prognostic factors, i.e. psychological and behavioral factors (‘yellow flags’) that could influence the progression to chronicity as well as socioeconomic and occupational factors (‘blue’ and ‘black’ flags), which could impact long-term work incapacity and delay the RTW (Grade A) ( Fig. 1 ). This assessment may require several consultations or interviews in complex cases (Grade A) and must be coupled with a thorough search for clinical symptoms of LBP severity (‘red flags’) regardless of the LBP stage: acute, subacute or chronic (Grade A)” .

3.2.1

Risk factors associated with chronicity

In the literature, psychosocial factors are considered as important factors to identify workers at risk of developing chronic pain and work disability. Socio-demographic and psychosocial data are intertwined and their usefulness may vary with the LBP stage. Their assessment must be combined according to a logical and practical screening sequence . The main factors are commonly grouped under the term “yellow flags” (term used today to describe psychosocial barriers to recovery) ( Fig. 1 ). They encompass emotional issues, inappropriate attitudes and behavior towards pain, as well as inappropriate pain-coping behaviors . They can be identified during the anamnesis of the worker. Their presence and, even more so their plurality are both associated to a greater risk of developing or maintaining chronic LBP and developing persistent disability . Other factors are also noted such as initial functional incapacity, general health status, presence of psychiatric comorbidities, or even, the negative opinion of patients regarding the hope of recovering or their RTW capacity . Regarding socio-demographic factors, some authors have identified some negative prognostic factors: i.e. low educational attainment, dissatisfaction during leisure activities, numerous children, being a single parent, being divorced or widowed without children and a large amount of domestic chores . Conversely, a low level of fear and avoidance, initial mild functional incapacity and the hope for recovery seem to be the most predictive elements for recovering on the middle and long term .

3.2.2

Work-related factors increasing the risk of progression towards long-term incapacity and delayed return-to-work

Data from the literature show that barriers to returning to work are less related to the LBP itself but rather to its context. Thus, the determinants of the LBP incapacity (and delayed return-to-work) are integrated within a dynamic biopsychosocial incapacity model . This biopsychosocial model underlines factors related to the individual, workplace system, healthcare system as well as the financial compensation system. All these previous factors can be grouped into prognostic factors related to the worker’s perceived representations of work and the environment (“blue flags”) and prognostic factors related to company policy, care systems and healthcare insurance (“black flags”) ( Fig. 1 ) . “Long-term incapacity work-related factors can be researched via several tools, which are difficult to implement in daily practice and those tools are rarely validated in French, besides the OMPSQ (Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire) (Grade AE)” .

It has been demonstrated that the negative representations workers have regarding pain and their “fears and beliefs” regarding consequences on continuing working are major determining factors of LBP incapacity, just like “fears and beliefs” from healthcare professionals and human resources in the company . This is the reason why some authors have developed the notion of “work disability diagnosis” to identify, for an employee on sick leave, the determinants of the LBP incapacity in the various systems involved . “In case of repeated and/or long-term sick leave > 4 weeks, it is recommended to explicitly address with the employee the representations or ‘beliefs’ regarding the link between LBP and work (Grade AE). If a questionnaire approach is used, the assessment of LBP-related beliefs can be done via the FABQ (Fear-Avoidance Belief Questionnaire), especially with the FABW-work subscale, which is a validated tool (Grade AE)” ( Table 1 ).