Postoperative Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation following arthroscopic shoulder surgery is as important as performing a technically sound procedure. Our general philosophy is that stiffness is a complication, but a retear of the rotator cuff or recurrence of instability is a failure. In most cases, stiffness in the postoperative period is transient and resolves with a stretching program (1). The incidence of resistant stiffness (stiffness resistant to stretching) with our rehabilitation protocols is extremely low (2). Moreover, as fully discussed in the next chapter (Chapter 21, “Shoulder Stiffness”), resistant stiffness can reliably be overcome with an arthroscopic capsular release. For these reasons, our protocols are conservative compared to some authors. Our evidence-based rehabilitation protocols emphasize healing first, followed by restoration of range of motion, and then strengthening. All our programs are surgeon directed with the initial exercises performed by the patient. Formal physical therapy is considered when strengthening begins or occasionally earlier if the patient needs additional assistance.

ARTHROSCOPIC ROTATOR CUFF REPAIR REHABILITATION PROTOCOLS

Historically, postoperative stiffness was one of the most devastating complications for open shoulder surgeons since there was no effective open surgical treatment for stiffness. Efforts to avoid stiffness led to the popularization of early passive range of motion following rotator cuff repair (3,4). Recent basic science investigations, however, have shown that early passive mobilization may actually encourage stiffness. Furthermore, early passive motion produces strains on the rotator cuff that can compromise healing. In a rat model of rotator cuff repair, Peltz el al. (5) demonstrated that immediate passive range of motion actually led to increased stiffness compared to a continued immobilization protocol. Sarver et al. (6) reported that immobilization following rotator cuff repair led to stiffness that was transient only. In addition to its role in the development of stiffness, immobilization following rotator cuff repair may lead to increased healing potential. Gimbel and colleagues found that immobilization led to enhanced mechanical properties of repaired rat supraspinatus tendons (7). In a histological evaluation of rotator cuff healing in a primate model, Sonnabend et al. (8) reported that maturation of the repaired rotator cuff requires 12 to 15 weeks. In summary, the above basic science investigations demonstrate that the ideal rehabilitation protocol to prevent stiffness and encourage healing following rotator cuff repair includes an initial period of immobilization.

In addition to the above information, our considerations in the rehabilitation protocol following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair include tear size, subscapularis involvement, concomitant labral repair, and propensity for postoperative stiffness (e.g., adhesive capsulitis and calcific tendonitis). Tear size, concomitant labral repair, and concomitant diagnoses affect the addition of early closed-chain passive forward flexion. Subscapularis tears affect the amount of immediate external rotation. Tear size and revision repairs affect the time to initiation of strengthening.

Partial-thickness Tears and Single-tendon Full-thickness Tears (≤3 cm)

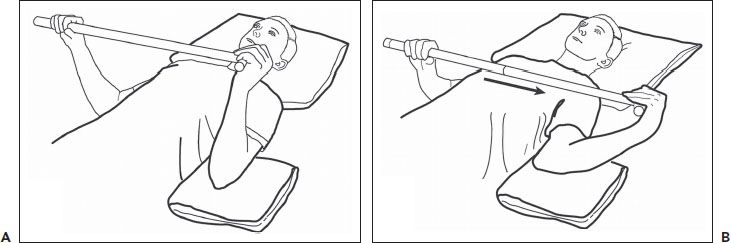

Patients with partial-thickness tears and single-tendon tears are more prone to postoperative stiffness. These patients are placed in a sling for 6 weeks, which they may remove for showering and meals. Elbow flexion and extension and hand and wrist exercises begin immediate post-op. We begin passive external rotation with a stick immediately post-op (Fig. 20.1). If there is an associated full-thickness subscapularis repair of more than 30% of the tendon, we restrict external rotation to 0°. With subscapularis tears of ≤30% of the tendon, we allow 30° of passive external rotation. Closed-chain passive forward flexion stretches via table slides begin immediately post-op (Fig. 20.2). The addition of this exercise alone decreased postoperative stiffness from 13.5% for partial-thickness tears and 7.3% for single-tendon tears in the report by Huberty et al. (9), to 0% in the report by Koo et al. (2) Patients are instructed to perform passive external rotation and table slide exercises twice daily; each stretch is held for 10 seconds, with 10 repetitions per set, for 2 sets.

At 6 weeks post-op, the sling is discontinued. Patients begin passive overhead forward elevation with a rope and pulley (Fig. 20.3) and supine overhead stretches using the opposite arm (Fig. 20.4). Passive external rotation with a stick is continued. Passive internal rotation is delayed until 12 weeks post-op as this places significant strains on the anterior supraspinatus and upper subscapularis.

Strengthening with elastic bands begins at 12 weeks post-op. This is our “4-pack,” which includes resisted internal and external rotation with the arm at the side, low row, and biceps curl (Fig. 20.5). The patient starts with the smallest diameter (yellow) elastic band and is encouraged to perform four sets of ten repetitions, twice a day. The patient progresses in band diameter as tolerated (red, then blue). The stretching program is continued during the strengthening phase.

Return to full activity is permitted at 6 months (Table 20.1).

Large, Massive, and Revision Rotator Cuff Repairs

The incidence of postoperative stiffness decreases as tear size increases and also decreases in revision cases. Consequently, for the first 12 weeks post-op, these patients follow the protocol outlined above with the exception that table slides are not performed immediately post-op. Strengthening is initiated at 12 weeks for large tears (3 to 5 cm). Strengthening is delayed until 16 weeks post-op for massive tears (>5 cm), tear involving an interval slide, or for revision repairs. Return to full activity is not allowed until 1 year post-op (Table 20.1).

Subscapularis Tendon Repair

In general, for most subscapularis tears, we delay external rotation beyond neutral until 6 weeks post-op. Other than that, the protocol is for the size of the major tear excluding the subscapularis. If the tear involves only a small portion of the upper subscapularis (≤30%), external rotation is allowed to 20° or 30° in the immediate postoperative period.

Biceps Tenodesis

A biceps tenodesis may be performed in conjunction with a rotator cuff repair. The rehabilitation protocol therefore is usually dictated by the standard protocol for the type of rotator cuff tear that was repaired. In either case, active flexion and extension of the elbow without resistance are allowed immediately post-op. In the absence of a rotator cuff repair, immediate closed-chain overhead motion is also encouraged (table slides). Strengthening is delayed until 12 weeks post-op since the patient will involuntarily contract the biceps when he or she is doing resisted internal and external rotation exercises.

Figure 20.1 Passive external rotation is performed with the patient lying supine and the normal arm using a stick to passively externally rotate the operative arm. Note that a towel is placed under the elbow of the operative arm to facilitate the exercise. A: Starting position. B: Ending position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree