Philosophy of Instability Repair

We have come a long way since the 1990s, when “experts” would openly debate whether arthroscopic instability repairs should even be done because of their high failure rate. Today, there is no question that most instability repairs can be successfully performed arthroscopically with a failure rate that is approximately the same as that of open instability repairs.

Two things have primarily been responsible for our improved results in arthroscopic instability repair. First of all, the techniques of arthroscopic Bankart repair have been greatly refined over the past decade. Second, the recognition that significant bone defects require bone grafting for successful results has largely eliminated the bone-deficient patient as a cause of failure of arthroscopic Bankart repair.

The senior author (SSB) recalls that, prior to incorporating the Latarjet reconstruction into his practice for cases of bone loss, the biggest unsolved problem in his shoulder practice was how to treat the unstable shoulder that had bone loss. Through the end of the 20th century, the conventional wisdom in the United States was that all shoulder instability could be addressed with soft tissue repairs. However, it was obvious that most of our failures of arthroscopic Bankart repair in the 1980s and 1990s were in patients with significant amounts of bone loss.

Dr. Joe DeBeer, after visiting Dr. Gilles Walch in Lyon, France, and seeing his success with the Latarjet procedure and its coracoid bone graft, convinced the senior author (SSB) that this procedure was the answer to the great unsolved problem in his practice. Over time, after adopting the Burkhart–DeBeer modification of the original Latarjet, the proof of its efficacy was clear. We owe a great debt of gratitude to Dr. Gilles Walch for preserving the nearly lost art of the Latarjet procedure and to Dr. Joe DeBeer for introducing this procedure to us.

WHEN TO OPERATE

Despite the incredibly high recurrence rates with nonoperative treatment of instability in athletic young people, many surgeons continue to recommend immobilization followed by rehabilitation as the preferred treatment in all first-time dislocators.

We disagree with that approach. For all active athletic individuals under the age of 30, we recommend arthroscopic Bankart repair after the first dislocation. In active patients over the age of 30, we may try nonoperative treatment after the first dislocation, but if they have a second dislocation, we usually advise arthroscopic Bankart repair. It has been our experience that, with repeated dislocations, bone loss and articular cartilage damage are rapidly cumulative. In fact, we have found that most people with recurrent dislocations whose total time with the shoulder “out of joint” (i.e., the total cumulative time between dislocation and reduction of all episodes of instability) is >5 hours will have significant bone loss that will require bone grafting. Our philosophy is that we would prefer to treat these patients with a less invasive arthroscopic procedure before their bone loss reaches a significant level, so we generally recommend arthroscopic repair after the first or second episode.

PHILOSOPHY OF ARTHROSCOPIC FIXATION

We believe that specific technical criteria must be satisfied in order to achieve successful arthroscopic instability repairs. These criteria have both mechanical and biologic components, and they include

Bone Loss Criteria

We have previously defined significant bone loss as

We found that arthroscopic Bankart repair in the face of one or both of these significant bone lesions led to an unacceptable recurrence rate of 67% (1). Therefore, we typically perform open Latarjet reconstructions in patients with significant bone loss. This procedure achieves stability in almost all patients by means of extending the articular arc of the glenoid so far that the Hill-Sachs lesion cannot engage, as well as by utilizing the sling effect of the conjoined tendon to augment the anterior stabilizing structures.

For small acute bony Bankart lesions, we typically repair the glenoid bone fragment with suture anchors. For large acute bony Bankart lesions (i.e., glenoid fractures), we perform arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation (ARIF) with cannulated screws.

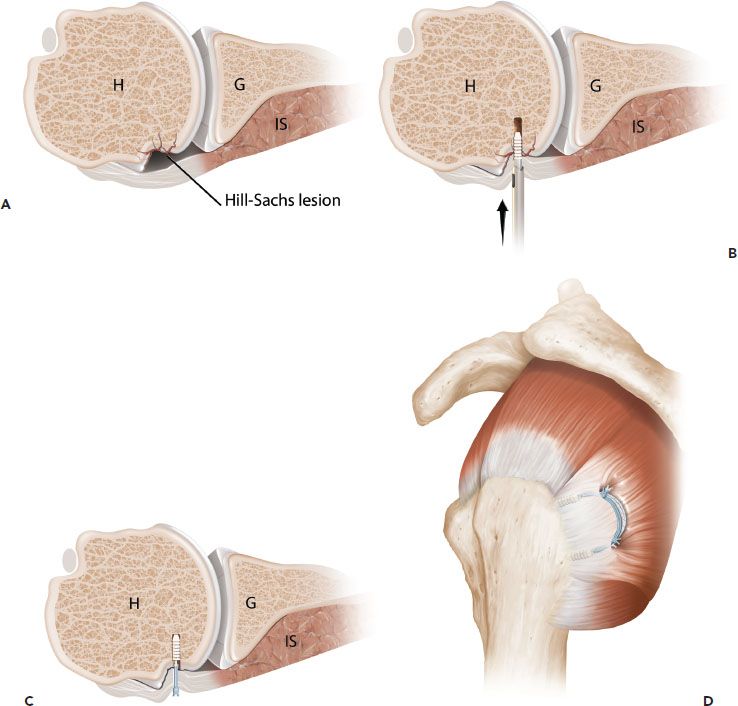

As with most things in life, there is a “gray zone” where the criteria are not so clear. The “gray zone” is the category of patients that have a relatively normal inferior glenoid diameter (i.e., <25% bone loss) with an accompanying deep Hill-Sachs lesion (≥4 mm deep). Dr. Phillippe Hardy found that patients with this combination of pathology had a high failure rate after arthroscopic Bankart repair, with a 61% rate of recurrent subluxation or dislocation (personal communication, 2009). In this clinical situation, we now augment our arthroscopic Bankart repair with an arthroscopic remplissage in which we inset the infraspinatus tendon into the humeral head defect and secure it with suture anchors (Fig. 11.1). In this way, we exclude the Hill-Sachs lesion from the humeral articular arc, changing it from an intra-articular bone defect to an extra-articular defect that can no longer engage the anterior glenoid rim. In addition to the obvious advantages for stability enhancement, we believe that this procedure repairs some of the footprint disruption of the infraspinatus that occurs with repeated dislocations (i.e., PASTA lesions of the infraspinatus that we see commonly in association with large Hill-Sachs lesions).

Soft Tissue Preparation

Soft tissue preparation revolves around the principle of optimal tension at the bone-soft tissue interface. The capsulolabral sleeve must be repaired in such a way that it is not too tight and not too loose. In cases with medialized soft tissue healing on the glenoid neck (anterior labral periosteal sleeve avulsion [ALPSA] lesions), the capsule and labrum must be dissected from the glenoid neck so that the underlying subscapularis muscle belly can clearly be seen deep to the capsule. Once the capsule has been adequately mobilized, it will “float up” to the level of the glenoid rim where it can be repaired to bone without tension.

On the other hand, if there is excessive laxity to the capsule, the laxity must be reduced by means of plication sutures. Some surgeons recommend capsular plication directly to the labrum if the labrum is intact, as in cases of multidirectional instability (MDI). However, most patients with MDI have hypoplastic, hyperelastic labra that do not provide firm anchorage points for plication. Therefore, in cases of MDI, we prefer to plicate using suture anchors in the glenoid, as the anchors will provide the firm fixation points we need. Also, in dealing with MDI, we pay special attention to plicating the axillary recess, which is always redundant in such cases.

For traumatic instability cases, we try to recreate a “bumper” of tissue at the glenoid rim. This visual “bumper” is usually attained only by achieving physiologic tensioning of the capsule. Our end point is to achieve centering of the humeral head on the bare spot of the glenoid (Fig. 11.2). When we see this centering, as viewed from an anterosuperolateral portal, we know that we have correctly retensioned the capsule.

The arthroscope offers the advantage of seeing all the pathology, but the surgeon must be sure to look at all the areas where pathology can occur. We have seen several cases where there was a Bankart lesion and a HAGL lesion in the same patient, requiring fixation on both the glenoid side and the humeral side. Furthermore, we have seen quite a few triple labral lesions (combined anterior Bankart, posterior Bankart, and superior labrum anterior and posterior [SLAP] lesion) in patients suspected of having only anterior instability. These lesions must all be recognized and fixed.

In the case of a triple labral lesion, the order of steps is very important. Our first area for anchor placement is for the SLAP lesion, where the supralabral recess tends to swell and close off early. Therefore, we place the SLAP anchors and pass the SLAP sutures early, but do not tie them until the final step of the procedure. Tying them early can close down the remaining capsular space, making it very difficult to do the Bankart repair. The next step is to place the most inferior anchors at the 5 o’clock, 6 o’clock, and 7 o’clock positions, to pass their sutures, and to tie them. The principle here is to perform the repair in the tightest working space first. After that, we place anchors anteriorly, pass their sutures, and tie those knots for an anterior Bankart repair. Then we do the posterior Bankart repair. The posterior repair is done last because visualization is easier posteroinferiorly, even after a Bankart repair has been done. Finally, we tie the SLAP sutures, completing the repair.

Figure 11.1 Schematic of remplissage for a Hill-Sachs lesion. A: Axial schematic of a Hill-Sachs lesion. B: Anchors are placed into the Hill-Sachs defect. C: Sutures are passed through the infraspinatus tendon and tied to inset the tendon into the defect. Insetting of the infraspinatus into the defect converts the Hill-Sachs lesion to an extra-articular defect. D: Sagittal oblique view demonstrates the mattress stitches between the two anchors that have been tied using a double-pulley technique. G, glenoid; H, humerus; IS, infraspinatus tendon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree