and Gautam M. Shetty2

(1)

Consultant Joint Replacement Surgeon Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Breach Candy Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

(2)

Consultant Arthritis Care and Joint Replacement Surgery, Asian Orthopedic Institute Asian Heart Institute and Research Center, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Abstract

Patients undergo TKA to gain relief from arthritic pain, to regain function and to improve their quality of life. However, the patient needs to deal with significant pain during the early postoperative period after TKA. Postoperative outcome and satisfaction after TKA depend to a large extent on optimal pain control. Suboptimal pain management after TKA has severe consequences. It may not only lead to physical and emotional distress and dissatisfaction in the patient and relatives but often leads to longer hospital stay, delay in functional recovery and non-compliance of patients with rehabilitation programme. Delay in mobilisation due to excessive pain may also put the patient at increased risk for systemic complications such as deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia and thromboembolism or local complications such as residual knee deformity (usually fixed flexion deformity), limited knee ROM (typically flexion beyond 100°) and chronic pain at the surgical site. Therefore, the importance of optimal pain control after TKA cannot be emphasised enough given the consequences.

Introduction

Patients undergo TKA to gain relief from arthritic pain, to regain function and to improve their quality of life. However, the patient needs to deal with significant pain during the early postoperative period after TKA. Postoperative outcome and satisfaction after TKA depend to a large extent on optimal pain control [1–3]. Suboptimal pain management after TKA has severe consequences. It may not only lead to physical and emotional distress and dissatisfaction in the patient and relatives but often leads to longer hospital stay, delay in functional recovery and non-compliance of patients with rehabilitation programme. Delay in mobilisation due to excessive pain may also put the patient at increased risk for systemic complications such as deep vein thrombosis, pneumonia and thromboembolism [4, 5] or local complications such as residual knee deformity (usually fixed flexion deformity), limited knee ROM (typically flexion beyond 100°) and chronic pain at the surgical site [6–8]. Therefore, the importance of optimal pain control after TKA cannot be emphasised enough given the consequences.

Postoperative physical rehabilitation after TKA is equally important to help the patient achieve full functional recovery as soon as possible. Rehabilitation and pain control go hand in hand, and optimal pain control is necessary to initiate early mobilisation and ambulation and achieve functional recovery. This chapter aims to discuss the postoperative pain control and rehabilitation protocol being followed by the authors.

Pain After TKA

Postoperative pain is a complex phenomenon and the aetiology of acute postoperative pain in TKA is still unclear. However, both systemic and local factors are known to play a role in it [9]. Patient-specific factors such as age, gender, aetiology of arthritis, prior experience, expectations and the psychological make-up all have been reported to play a part in how postoperative pain is perceived and experienced after TKA [10, 11]. Intraoperatively, local factors such as the amount and depth of soft-tissue dissection or release, optimum limb alignment, component alignment and rotation and the soft-tissue balance achieved may have an association with recovery from acute postoperative pain and the risk of chronic persistent pain after TKA [9, 12–14]. Postoperatively, it has been reported that control of the local rather than systemic inflammatory response may be more important for early postoperative functional recovery [15].

In view of various systemic and local factors involved in acute postoperative pain, a multimodal approach to pain control has now become standard practice in patients undergoing TKA [16, 17]. The principle of this multimodal approach is to deploy various techniques and pharmacological agents which will act synergistically at different levels to achieve optimal pain control after TKA. The authors use a similar multimodal pain control protocol involving preoperative patient education, pre-emptive analgesia, optimal anaesthesia and surgical technique and postoperative analgesia in order to minimise pain and facilitate early functional recovery of the patient after TKA.

Multimodal Pain Management Protocol

Preoperative Patient Education

This involves educating the patient about the surgical procedure and postoperative recovery course after TKA. The patient is appraised about what to expect in terms of pain, complications and the time to reach a pain-free, fully functional joint after TKA. Patients are also encouraged to contact and discuss with patients who have already undergone TKA and have now fully recovered.

Pre-emptive Analgesia

After admission (previous night at 10 p.m.) – Tab etoricoxib 60 mg and tab gabapentin 300 mg

Morning of surgery (at 6 a.m.) – Tab etoricoxib 60 mg and tab gabapentin 100 mg

Anaesthesia

Spinal anaesthesia (unilateral TKA) or combined spinal + epidural (for bilateral TKA)

Surgical Technique

Skin incision only as much as required (usually extending from the upper pole of the patella to the tibial tuberosity)

Minimise soft-tissue release by excision of osteophytes before any soft-tissue release, graduated stepwise soft-tissue release and reduction osteotomy before any substantial release in case of varus deformity

Full correction of knee deformity in both coronal and sagittal planes, optimum component alignment and soft-tissue balance

Complete homeostasis and airtight closure to minimise chances of a postoperative haematoma and facilitate proper wound healing

Intraoperative Local Infiltration

What to infiltrate?

The periarticular infiltration “cocktail” contains the following constituents diluted to a total volume of 50 ml with 0.9 % normal saline:

Bupivacaine 0.25 % (2.5 mg/kg)

Fentanyl 200 mcg (50 mcg/ml)

Cefuroxime 750 mg

Triamcinolone 40 mg

Ketorolac 30 mg

Clonidine (1 mcg/kg)

The corticosteroid is excluded in patients with diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, previous knee surgery and any immunodeficiency disease.

Where to infiltrate?

Edges of the arthrotomy, medial collateral ligament, lateral retinaculum and posteromedial soft-tissue sleeve

When to infiltrate?

After the components have been implanted and while the cement is setting

Postoperative Analgesia

First 48 h

Tab paracetamol 650 mg 8 hourly + tab ibuprofen 400 mg 12 hourly + diclofenac suppository 12.5 mg, one at night + tab etoricoxib 60 mg, one in the morning + tab gabapentin 300 mg, one at night

Local ice fomentation every 6–8 h

After 48 h till suture removal (2 weeks)

Tab paracetamol 650 mg 8 hourly + diclofenac suppository 12.5 mg, one at night + tab etoricoxib 60 mg, one in the morning + tab gabapentin 300 mg, one at night

Tab ibuprofen 400 mg 12 h or as and when needed

Local ice fomentation every 6–8 h

After suture removal till 1 month

Tab paracetamol 650 mg 8 hourly + tab meloxicam 15 mg, one in the morning + tab etoricoxib 60 mg, one at night + tab gabapentin 300 mg, one at night

Tab ibuprofen 400 mg as and when needed

Local ice fomentation every 6–8 h

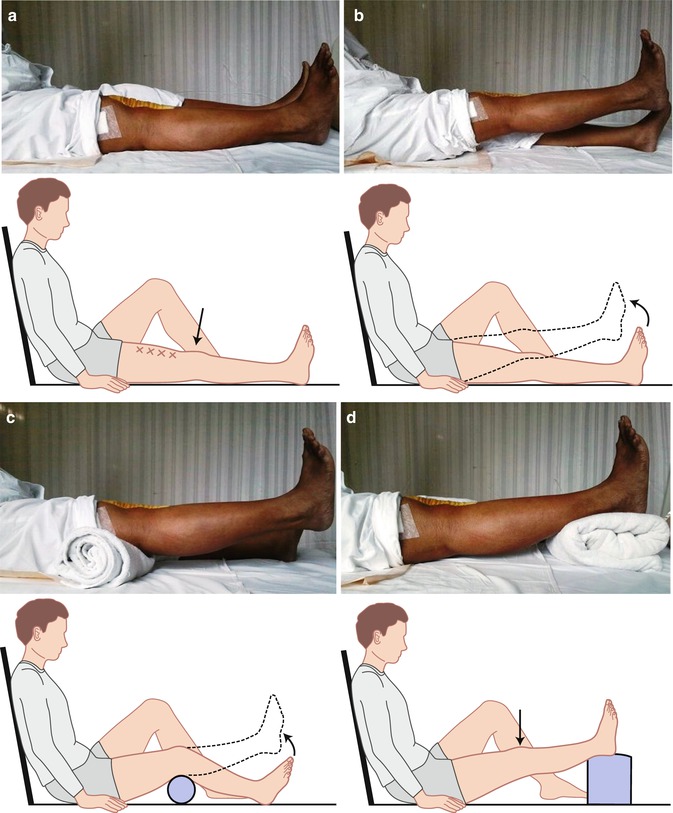

Rehabilitation Protocol

All our patients are instructed and trained in five basic, simple exercises (Fig. 12.1) which need to be performed regularly throughout the day (10– 20 repetitions each, in 3–4 sessions per day). The patients are made familiar with these five exercises preoperatively using an illustrated instruction booklet which the patient can refer to from time to time postoperatively, and a resident/fellow/therapist demonstrates these exercises on day 1 postoperatively. Subsequently, till the time of discharge, the patient is assessed everyday by the surgeon for progress in knee motion and functional ability. A physiotherapist is asked to intervene only in special cases with excessive quadriceps weakness, slow improvement in knee flexion or gait abnormality.