and Gautam M. Shetty2

(1)

Consultant Joint Replacement Surgeon Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Breach Candy Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

(2)

Consultant Arthritis Care and Joint Replacement Surgery, Asian Orthopedic Institute Asian Heart Institute and Research Center, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Abstract

Preoperative planning is paramount before undertaking any surgical procedure. This cannot be overemphasised for a procedure like total knee arthroplasty (TKA) where the goals include accurate restoration of limb alignment, optimum soft-tissue balancing and achieving a satisfactory range of motion (ROM). The use of computer navigation during TKA does not diminish the role of preoperative planning. The first important step in preoperative planning is proper selection of the patient and a thorough physical examination. This step gives important clues regarding patient complaints and disability and the expectation which a patient may have from the procedure. Physical examination may reveal clues as to what to expect during surgery in terms of pathoanatomic changes in the arthritic joint and how to be plan for it during surgery. Imaging using plain radiographs helps in confirming the extent of knee arthritis and severity of deformity and is useful for planning the procedure. This chapter elaborates on physical examination and imaging for a patient who is to undergo TKA.

Introduction

Preoperative planning is paramount before undertaking any surgical procedure. This cannot be overemphasised for a procedure like total knee arthroplasty (TKA) where the goals include accurate restoration of limb alignment, optimum soft-tissue balancing and achieving a satisfactory range of motion (ROM). The use of computer navigation during TKA does not diminish the role of preoperative planning. The first important step in preoperative planning is proper selection of the patient and a thorough physical examination. This step gives important clues regarding patient complaints and disability and the expectation which a patient may have from the procedure. Physical examination may reveal clues as to what to expect during surgery in terms of pathoanatomic changes in the arthritic joint and how to plan for it during surgery. Imaging using plain radiographs helps in confirming the extent of knee arthritis and severity of deformity and is useful for planning the procedure. This chapter elaborates on physical examination and imaging for a patient who is to undergo TKA.

The Patient

Studies have shown that patient demographics are changing and increasingly younger, heavier, and more active patients with higher expectations are coming up for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [1–3]. Patient satisfaction regarding TKA is primarily based on postoperative pain, ROM and functional ability and absence of complications related to TKA. An initial assessment of the patient should address issues related to patient’s expectations and apprehensions regarding the surgical procedure. Studies have shown that patients with high somatisation and depression scores preoperatively continue to remain dissatisfied with the outcome of joint replacement despite lack of clinical or radiographic reasons for it [4–6]. Although the presence of psychological disorder is not a contraindication for surgical intervention, these issues need to be considered by the surgeon. With simultaneous bilateral TKAs, issues that frequently concern patients are whether the procedure will be more painful, the postoperative functional recovery slower and if they have to be dependent on others for their daily activity after surgery compared to staged bilateral TKAs (SBTKAs) or unilateral TKAs. An uneventful postoperative recovery and the risk of complications after SBTKA are also major concerns with patients. The authors in a prospective study conducted at their centre found that pain, function and complication rates in patients who underwent simultaneous bilateral computer-assisted TKA were comparable to those who underwent unilateral TKA [7]. Hence, the surgeon needs to address these issues before surgery so that patients can take an informed decision.

Physical Examination

Before examining the knee, an assessment of gait and functional disability of the patient is invaluable. An abnormal gait with severe waddling or knee instability may be one of the features in patients with arthritic knee pain. Evidence of lateral thrust of the tibia or knee hyperextension during gait may indicate severe laxity or incompetence of the lateral collateral ligaments and posterior capsule, respectively (Fig. 1.1). Patients walking with severe intoeing or outtoeing may indicate a torsional abnormality in the limb.

Fig. 1.1

Clinical photographs of various types of deformities encountered in knee arthritis. (a) Patient has a combination of severe bilateral varus and fixed flexion deformities of the knees. (b) Note the lateral subluxation of the tibia on the left side (arrow) on weight bearing indicating overstretched lateral soft-tissue structures. (c, d) Patient has a combination of valgus and fixed flexion deformity of the knee. The patient also has severe bilateral flatfeet and hindfoot valgus. (e) An uncommon recurvatum deformity of the knee

Examination of the knee per se includes noting the type and degree of knee deformity, joint range of motion, instability, patellar tracking and condition of the skin over the knee joint. A combination of severe flexion or hyperextension deformity along with varus or valgus deformity adds to the complexity of the surgical technique (Fig. 1.1). Knees with severe instability or recurvatum deformity entail minimal bony resection and the possibility of using constrained prosthesis. The presence of knee recurvatum should alert the surgeon about the possibility of a neurological condition. This should be investigated and documented whenever necessary. Severe knee stiffness or severe flexion deformity indicates the need for a thorough posterior clearance or release with more liberal bone cuts to correct the deformity. In cases with severe stiffness or flexion deformity, quadriceps function may be difficult to assess, and any weakness will be revealed only after the TKA. Hence, such patients may require prolonged aggressive physiotherapy with or without splints (e.g. push-knee splint) postoperatively. Apart from the knee, a thorough examination of the entire lower limb is also warranted. Abnormal torsion of the tibia using the two malleoli as landmarks helps in deciding the rotational position of the tibial tray during TKA. Abnormal torsion in the tibia needs to be taken into account while determining rotational placement of the tibial component, or a mobile-bearing design may have to be used in order to avoid femoral and tibial rotational mismatch and postoperative gait abnormalities. Examination of the hindfoot similarly should be part of patient assessment. Both varus and valgus knees may be commonly associated with hindfoot valgus (Fig. 1.1). This tends to persist even after accurately correcting the knee deformity and influences the weight-bearing axis [8]. Hence, in cases with severe flat feet and hindfoot valgus, a medial arch support may be needed after surgery in order to improve the stance and gait of the patient. Proximally, the hip needs to be examined to rule out any hip pathology which may contribute to referred pain in the knee.

A fixed external rotation deformity of the hip especially in the very obese may lead to technical difficulties during the surgical procedure. Apart from these, a general assessment of peripheral limb circulation and neurological assessment and an assessment of the lumbar spine are important as any pathology related to these regions may have an effect on the postoperative functional and pain outcome of TKA. In fact it has been shown that nearly half the dissatisfied patients with an otherwise satisfactory TKA actually have symptoms related to the spine [9].

The condition of the contralateral limb and knee and that of the other joints as well as overall general physical condition of the patient needs to be assessed as these also influence postoperative satisfaction [9]. Overloading of the contralateral knee may predispose it to accelerated degenerative changes, while presence of fixed flexion or varus deformity may require compensatory footwear to correct limb length. Severe deformities may require bilateral TKAs to be performed.

Imaging

Plain Radiographs

Patients being considered for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) need to be investigated primarily using plain radiographs (either conventional or digital) such as the weight-bearing full-length hip-to-ankle radiograph, weight-bearing anteroposterior view and lateral and skyline views of the knee. These radiographs help in assessing the type and extent of knee deformity, the degree of joint space loss and bone loss, the amount of lateral or medial laxity, the distribution and amount of osteophytes and loose bodies, the presence of extra-articular deformities or pathologies and the general bone quality in the patient. Preoperative radiographs are also invaluable in planning the procedure and determining the technical difficulty that the surgeon may encounter.

Weight-Bearing Full-Length Hip-to-Ankle Radiograph

Controversy surrounds the use of weight-bearing hip-to-ankle radiographs in planning TKA. The use of these radiographs in cases with extra-articular deformities is generally accepted. Although their use in uncomplicated cases has been disputed [10–12], several reports have advocated their use routinely [13–16]. The authors obtain a weight-bearing long hip-to-ankle radiograph in all cases for TKA routinely not only to rule out extra-articular pathologies or deformities but also since most of the planning and radiographic assessment such as degree of deformity, plane of bone resection, amount of joint laxity and position of the femoral and tibial components in the coronal plane are done with respect to the mechanical axes of the femur and tibia. The following angles and radiographic features can be determined with this radiograph:

Frontal or Coronal Alignment – Relying on standard knee anteroposterior radiographs may grossly underestimate the knee deformity when compared to long hip-to-ankle radiographs especially in cases with severe coronal bowing of the femur (Fig. 1.2) which is common in patients with knee osteoarthritis [16–18]. The long hip-to-ankle radiograph helps in accurate estimation of preoperative knee deformity measured as the hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle. This is defined as the angle between the mechanical axis of the femur (centre of the femoral head to the centre of the knee) and mechanical axis of the tibia (centre of the knee to the centre of the tibial plafond).

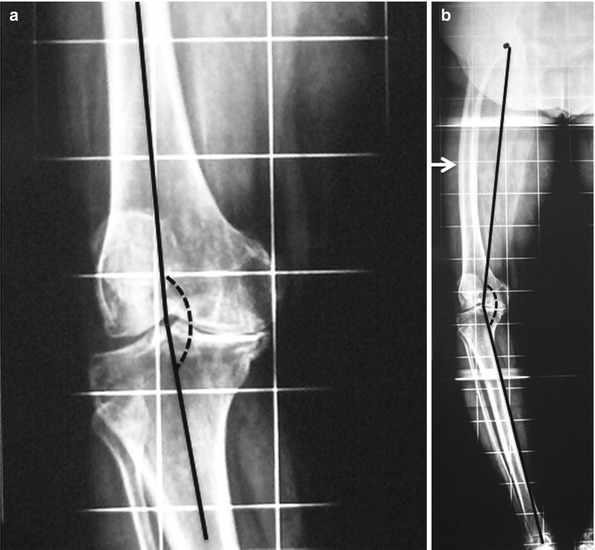

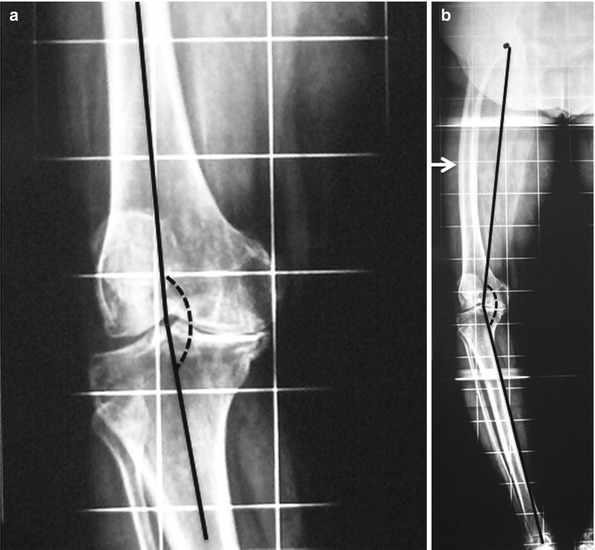

Fig. 1.2

Short films can be misleading! (a) A standing anteroposterior knee radiograph shows 4° varus deformity of the knee when calculated using the anatomic axes (femorotibial angle or FTA). (b) Weight-bearing long hip-to-ankle radiograph of the same patient shows that the deformity is approximately 20° when calculated using the mechanical axes (hip-knee-ankle or HKA angle). Note the extra-articular deformity caused by severe coronal bowing of the femur (arrow)

Distal Femoral Resection – The distal femoral valgus correction angle (VCA) decides the valgus angle at which the distal femur needs to be cut in the coronal plane in order to align the femoral component perpendicular to the mechanical axis of the femur. This is calculated as the angle between the mechanical axis of the femur and the distal anatomic axis of the femur (Fig. 1.3). Although the VCA is commonly believed to be between 5° and 7°, a recent study by the authors involving 503 arthritic limbs has shown wide variation in its value among patients with knee arthritis [18]. It may vary between 2.6° and 11.4° with 56 % of the limbs having a VCA outside the 5–7° range [18]. The percentage of limbs with VCA >7° was significantly more in varus knees and with VCA <5° more in valgus knees. Preoperative deformity showed significant correlation with VCA. The VCA can also be affected by excessive coronal bowing of the femoral shaft or variation in the femoral neck shaft angle. Excessive coxa vara and lateral femoral bowing both increase the VCA, and excessive coxa valga and medial femoral bowing have the reverse effect [18]. During conventional TKA, extremes of VCA will render use of an intramedullary femoral guide rod difficult due to distortion of the femoral canal and may lead to error in placement of the distal femoral cutting block. Hence, in these cases, a shorter guide rod needs to be used, and owing to such great variability among limbs, the VCA should be selected in each limb based on measurements done on preoperative long films. Although extremes of VCA or extra-articular deformity are irrelevant when placing the femoral component in computer-assisted TKA (as the software uses only the centre of the femoral head and centre of distal femur to plan the distal cut), these findings on the long weight-bearing radiograph may indicate the need for extensive soft-tissue releases for restoration of limb alignment and optimum gap balancing during TKA irrespective of the technique used (Fig. 1.4). When knee varus is associated with minimal osteophytes and a high VCA due to excessive femoral bowing, extensive soft-tissue release may have to be combined with a sliding medial condylar osteotomy during TKA [19].

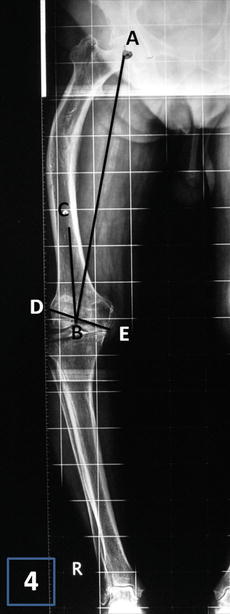

Fig. 1.3

Distal femoral valgus correction angle (VCA). Distal femoral valgus correction angle (VCA) decides the valgus angle at which the distal femur needs to be cut in order to align the femoral component at 90° to the mechanical axis of the femur. This is calculated as the angle (angle ABC) between the mechanical axis of the femur (line AB) and the distal anatomic axis of the femur (line CB)

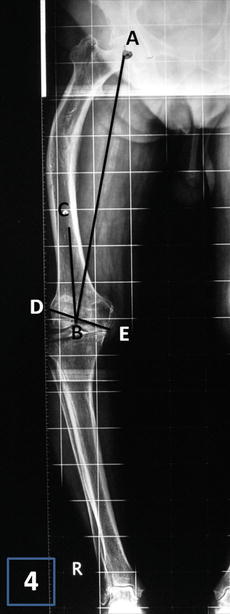

Fig. 1.4

Extreme of distal femoral valgus correction angle (VCA). A case of extreme distal femoral valgus correction angle (angle ABC) of 17° due to a malunited femoral fracture. The distal femoral cut (line DE) drawn perpendicular to the mechanical axis of femur (line AB) endangers the femoral attachment of lateral collateral ligament. Hence, a corrective osteotomy of the extra-articular deformity is warranted

Preoperative Joint Divergence Angle (JDA) – Varus knee deformities are associated with tight medial and lax lateral and soft-tissue structures. A fair indication of these soft-tissue changes can be obtained on a weight-bearing full-length radiograph. The proposed distal femoral and proximal tibial cuts are drawn perpendicular to the mechanical axes of the femur and the tibia. The angle formed by the proposed tibial and femoral resections (preoperative JDA) will give a fair estimation of the site (medial or lateral) and degree of soft-tissue contracture and the extent of soft-tissue release that may be required. Similarly, it will also give a fair estimation of the degree of laxity in the opposite compartment and how much bone resection may be required. Lesser the angle or more parallel the lines, lesser will be the amount of release required for correction (Fig. 1.5a, b). Similarly greater the angle or more divergent the lines, greater will be the amount of release required and more conservative the bone cuts (Fig. 1.5c).

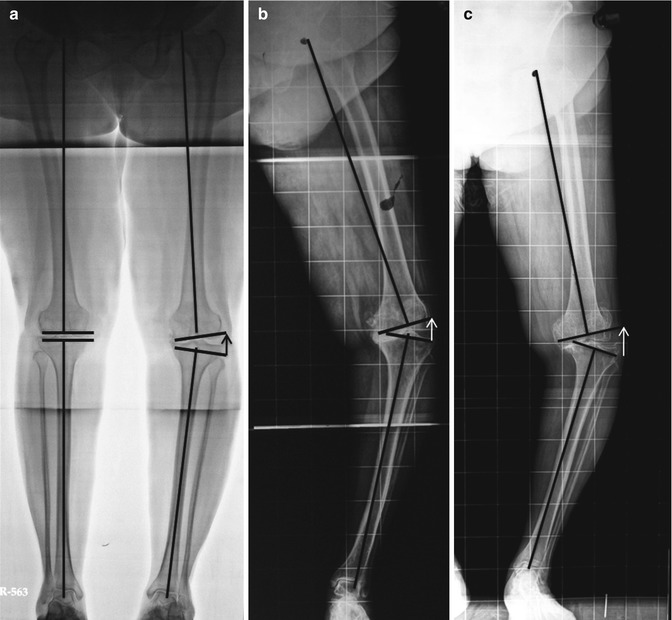

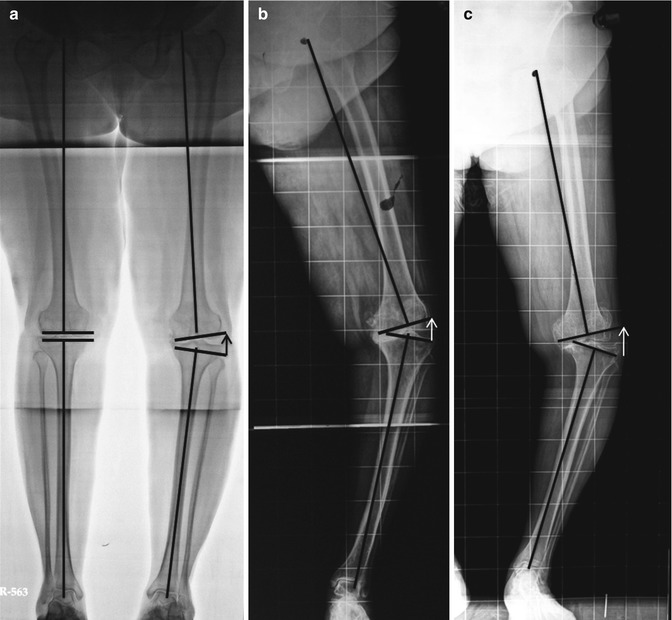

Fig. 1.5

Preoperative joint divergence angle (JDA). (a) Mild varus deformity on the right side where the distal femoral and proximal tibial resection planes are parallel to each other (JDA almost zero) implying that minimal medial soft tissue is needed for gap balancing; on the left side with moderate varus deformity, the lateral side shows moderate laxity (arrow). (b) An example of severe lateral laxity due to severe varus deformity. This case will require substantial medial release in order to balance it with the lateral side especially due to the associated femoral shaft bowing present. (c) Here the lateral laxity is very severe with associated lateral subluxation of the tibia despite the degree of varus deformity being lesser than in patient (b) creating a large JDA

Extra-Articular Deformities or Implant In Situ – A full-length radiograph will also reveal any extra-articular deformity (EAD) in the limb, hip pathology, prior trauma/surgery, associated stress fractures or an implant in situ. Excessive coronal bowing of the femur is a common cause of extra-articular deformity in arthritic knees undergoing TKA [16, 17]. Mullaji et al. [16] have reported that up to 20 % of varus arthritic knees have significant femoral bowing in the coronal plane in Asian patients. Stress fractures although uncommon are an important cause of extra-articular deformity [20]. Depending on the type seen on preoperative radiographs, TKA may have to be combined with long tibial stem extenders, metal augments or corrective osteotomies [20]. Similarly, in the tibia, extra-articular deformity due to malunited or ununited fractures, stress fractures, post-high tibial osteotomy or excessive tibial bowing may be present. Although most of these cases of knee arthritis with extra-articular deformities can be managed by extensive intra-articular soft-tissue releases, a corrective osteotomy may be rarely required [17]. This is discussed in detail in Chap. 8 on EADs.

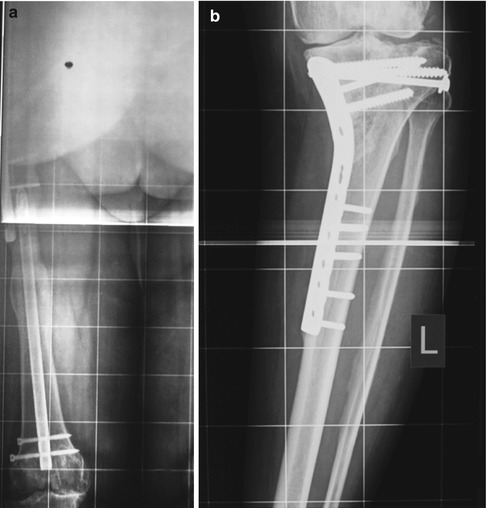

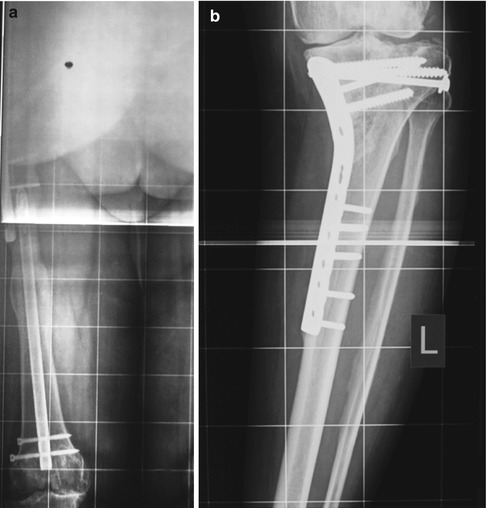

The presence of implants will warrant the need to use computer navigation which will bypass the hardware or extramedullary cutting guides as use of intramedullary jigs may not be possible (Fig. 1.6a). However, in some cases where the implant may be close to the knee joint, they may have to be removed before implantation of the prosthesis especially the tibial component (Fig. 1.6b). We have shown that navigation is useful in cases of altered hip centre [21].

Fig. 1.6

Implant in situ. (a) A case with intramedullary nail in the femur which will not interfere during CAS TKA. (b) A case with proximal tibial plating with a malunited fracture. Implant needs to be removed and a corrective osteotomy may be required

What to Look for in a Weight-Bearing Long Hip-to-Ankle Radiograph?

Degree of limb malalignment or deformity based on hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle.

Distal femoral valgus correction angle (VCA) – the greater the angle, the greater the need for an extensive soft-tissue release with or without an osteotomy.

Extra-articular deformity – is a corrective osteotomy required?

Stress fractures, prior trauma.

Prior surgery with implant in situ and hip pathology.

Weight-Bearing Knee Anteroposterior (AP) Radiograph

The knee AP view is probably the most commonly used radiograph for diagnosis of knee arthritis and planning for TKA. It is important that the knee AP view is obtained while the patient is weight-bearing as a supine view may underestimate the degree of arthritis, deformity and instability. This view allows a closer look at the knee in the coronal plane and is an important part of the preoperative planning process for TKA. As previously mentioned, although this view may underestimate the degree of knee deformity and will not show extra-articular bony deformity, it is invaluable in assessing certain features around the knee joint which gives an idea of what to expect during TKA.

Tibial and Femoral Resection – Tibial and femoral resections are performed perpendicular to their respective mechanical axes. Traditionally, the amount of tibial resection is primarily based on the actual thickness of the thinnest tibial component. If the composite thickness is 8 mm, then generally 8 mm of the less affected tibial plateau should be resected. However, both tibial and femoral resections need to be conservative in cases with severe bone loss, severe lateral or medial laxity in varus or valgus, recurvatum deformity and in knees with gross instability. More than usual distal femur may have to be occasionally resected in knees with fixed flexion deformity to achieve correction. By marking out these resections, the surgeon can get a good idea of the amount of bone being resected, and if the relative thickness of the medial and lateral tibial plateau and distal femur condyles matches the preoperative markings.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree