Postoperative and Preprosthetic Care

Michelle M. Lusardi

Learning Objectives

On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to do the following:

Patient-client management after amputation

Individuals with New Amputation

In the early days following surgery, the person with a new amputation is likely to experience acute surgical pain and is likely to be grieving the loss of his or her limb. The immediacy of pain combined with a sense of loss may make it difficult for those with recent amputation to recognize their potential for a positive rehabilitation outcome.1 Older persons with dysvascular or neuropathic limb loss may have had time to physically and psychologically prepare for an elective amputation after a prolonged period of managing a poorly vascularized foot or nonhealing neuropathic ulcer, and therefore may be somewhat less distressed about the loss of their limb than younger persons who have suddenly lost a limb in a traumatic accident or other medical emergency. Whatever the circumstances leading to amputation, however, the loss of one’s limb requires significant psychological adjustment.2 Early education and discussion about the process of rehabilitation and the person’s ultimate goals are extremely important.3

Patient-Centered Care and Multidisciplinary Teams

In response to the numbers of military personnel with traumatic amputation and to older veterans with dysvascular amputation, the Departments of Defence and of Veterans Affairs have adopted interdisciplinary, patient-centered care as the ideal model for rehabilitation of persons with amputation.4,5 The physical therapist and prosthetist, as members of the rehabilitation team, will interact with surgeons, patients, and family members as decisions about surgical levels, plans for postoperative care, potential for prosthetic use, and prosthetic rehabilitation plans are made. For persons facing elective amputation because of dysvascular disease, a period of PT intervention prior to surgery can positively impact on postoperative outcomes.6

In the days immediately after amputation, this initial stage of acute care and early rehabilitation sets the stage for eventual return to functional mobility, ability to return to valued activities, and participation in key family and social roles.4 Although the immediate goals of each member of the interdisciplinary team vary, all ultimately lead toward the person with a newly amputated limb’s independence and return to his or her preferred lifestyle. To accomplish this, the team must use an holistic and comprehensive approach to address the person’s comorbid burden of illness and psychological and developmental needs, as well as his or her long-term functional, vocational, and leisure goals. Surgical and medical members of the team are most concerned about the healing suture line and overall health status, especially for individuals with vascular insufficiency and for those at risk of infection after traumatic amputation.7 Nursing professionals provide general medical and wound care as the suture line heals, and administer medications for pain management.8 Registered dieticians assess the patient’s nutritional needs related to wound healing and exercise demands.9 Physical and occupational therapists focus on enhancing the patient’s early single limb mobility, self-care, assessment of the potential for prosthetic use, control of edema and pain management, optimal shaping of the residual limb for prosthetic wear, and prevention of secondary complications.10

The prosthetist may fabricate an immediate or early postoperative prosthesis or semirigid dressing and begins to consider which prosthetic components and suspension systems will ultimately be most appropriate, given the individual’s characteristics and functional needs.11 The person with new amputation and his or her family are often most concerned about pain management and what life will be like without the lost limb.12 A psychologist, social worker, vocational counselor, or school counselor is involved as needed to help with psychological adjustment and to organize long-term rehabilitation care or community resources in preparation for discharge.13 A clergyman can also be a valuable resource for the person with new amputation, the family, and the team.

Although the multidisciplinary team can vary in size, depending on patient needs and practice settings, the members at the center are the individual with new amputation and his or her caregivers.14 Communication among all team members, especially the opportunity for the person and family members to ask questions and voice concerns, is more important in this early postoperative and preprosthetic period than it is during the process of prosthetic prescription and training later in the rehabilitation process. This early period sets the stage for the individual’s expectations, and ultimately success, as a person with an amputation.14

The unique training, clinical expertise, and individual roles of each team member contribute, in a collaborative process, to the development of a plan for rehabilitation that best meets the needs and optimizes the potential of the individual who has lost a limb.6 The team must come to agreement on the timing and prioritization of specific rehabilitative interventions to meet the goals defined for each patient. Effective communication and strong relationships among the surgeons, orthopedists, or trauma teams who perform the majority of amputations and the rehabilitation team substantially improve the quality of patient care and assist the rehabilitation process.

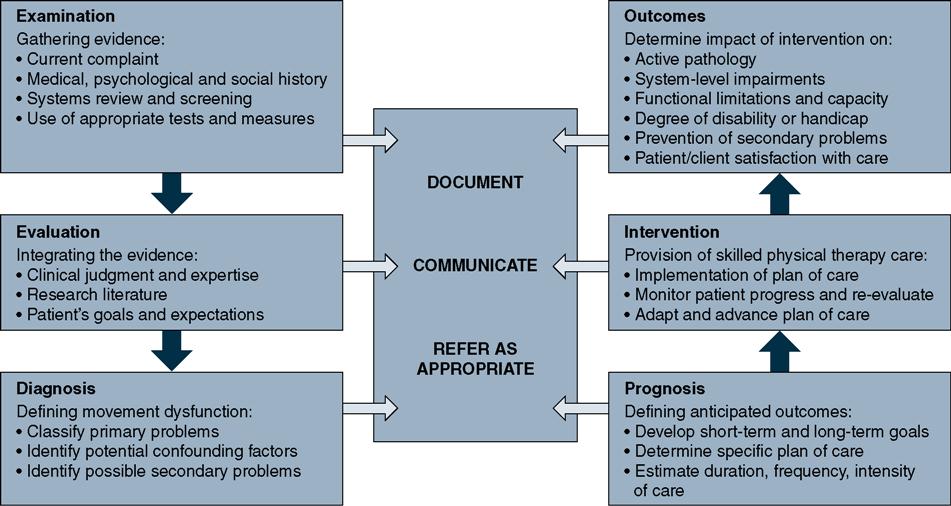

This chapter focuses on the roles of rehabilitation professionals who work with persons with new amputation in the days and weeks immediately after surgery. It explores how surgical pain and phantom sensation are managed, strategies for controlling postoperative edema, and methods to assess a patient’s readiness for prosthetic fitting. Interventions that help a person with new amputation gain competence with single limb mobility tasks and exercises that provide the foundation for successful prosthetic use are identified. The strategies for patient management are organized around the model outlined in the American Physical Therapy Association’s Guide to Physical Therapist Practice (Figure 20-1).15

Examination

Ideally, for those undergoing a “planned” or “elective” amputation, the rehabilitation team will meet with the individual and caregivers before surgery to begin collecting information that will be used to guide intervention and provide information about the rehabilitation process. In some instances, input from rehabilitation professionals may be sought by trauma surgeons to assist patients and families in making informed decisions when faced with amputation after severe injury of the limb. Preoperative interaction may not always be possible, especially when amputation occurs subsequent to failed revascularization, acute and severe limb ischemia, severe infection, or civilian or combat-related traumatic injury. If preoperative assessment is not possible, referral to rehabilitation should be made as soon after surgery as possible; delaying referrals often leads to contracture formation, further cardiovascular and musculoskeletal deconditioning, delayed prosthetic fitting and training, a greater risk of dependency, and a higher risk of reamputation, institutionalization, and mortaltity.16,17 Box 20-1 summarizes the components of a comprehensive assessment for persons with lower extremity amputation.

Whenever the first contact with the individual and family occurs, the rehabilitation team begins by gathering baseline information that will guide planning for and implementing of the rehabilitation process. This initial information is gathered in three ways: developing a complete patient–client history, performing a review of physiological systems to identify important comorbidities that will affect the rehabilitation process, and using appropriate tests and measures to identify impairments and functional limitations to be addressed in the rehabilitation plan of care.18 The volume and complexity of information needed to guide planning for prosthetic rehabilitation means that information gathering is a somewhat continuous process and must be integrated with early mobility training in preparation for the individual’s discharge from the acute care setting. Examination in the acute care setting likely focuses on four priorities: initial healing of the surgical site, pain management and volume control of the residual limb, bed mobility and transfers, and readiness for single limb ambulation. Examination later in the preprosthetic period (in an outpatient, home care, or subacute setting) would add more detail to determine potential for prosthetic prescription.

Patient-Client History and Interview

Rehabilitation professionals use several strategies to gather information about an individual’s medical history. In the acute care setting, the process usually begins with a review of the individual’s current medical record or chart, as well as previous medical records (if available). The chart review process provides a broad overview of the individual’s health, comorbidities, current medications, previous and current functional status, as well as details about the surgical procedure. Data that other members of the health care team have generated in their examination and evaluative processes are quite relevant to PT care, not only to avoid redundancy in examination but also in planning what additional information will be necessary to collect during subsequent interviews and discussion with the individual and family caregivers.

The interview process provides key information about the individual’s priorities and concerns so that they can be appropriately integrated into the plan of care. The physical therapist may also choose to gather supplementary information from the clinical research literature at this point to assist in the subsequent development of prognosis and plan or care, especially if the individual’s situation is unusual or complex.19

Demographic and Sociocultural Information

The information gathered when reviewing history often begins with basic demographics such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, primary language, and level of education. These data help us to appropriately target communication during our interaction with an individual with recent amputation. It is also important to build an understanding of the individual’s sociocultural history including beliefs, expectations and goals, preferred behaviors, and family and caregiver resources, as well as access to and quality of informal and formal support systems.20–22 Each of these is a potentially important influence on the individual’s engagement in the rehabilitation process. Rehabilitation professionals also gather information about the individual’s employment status and task demands, roles and responsibilities within the family system, and leisure interests and hobbies, as well as previous and preferred involvement in the community (access, transportation, and key activities). Additionally, information about smoking, alcohol intake, and other previous substance use/abuse, as well as the individual’s coping style and preferred coping strategies help the team to better understand how the individual may behave in the postoperative period. This information is important in developing a prognosis and plan of care; it helps rehabilitation professionals to better define the long-term goals and anticipated outcomes of rehabilitation.

Developmental Status

Another piece of information that informs an appropriate rehabilitation plan of care is the physical, cognitive, perceptual, and emotional developmental status of the individual and his or her caregivers, as well as an understanding of the family system as an organization.23–25 Although the relevance of developmental status is most obvious when the individual being examined is a child, the perspective afforded by understanding of life span development is valuable for individuals with recent amputation of any age. Examples of factors that evolve over the life span that affect an individual’s participation in rehabilitation include postural control, motor abilities, perceptual abilities, willingness to take risks, problem solving, coping styles and strategies, and limb dominance. Observation and interchange during the interview process help the therapist to determine if further clinical examination of developmental status will be necessary.

Living Environment

Rehabilitation professionals gather information about the characteristics of an individual’s physical living environment.26 They ask about getting into and out of the house (e.g., how far is it from the car to the house? What kind of surfaces will be encountered moving from the car to the house? Are there steps and railings at the entry? What are the distances between the major living areas that the person will have to navigate? How accessible and functional are each of the major living areas in the home for those using ambulatory aids or a wheelchair for mobility? Is it possible to adapt the home if necessary? What adaptive equipment is already available? What type of assistance is likely to be routinely available? What type of equipment is likely to be acceptable for the individual and family?).

Asking about the individual’s ability to drive, access public transportation, or plans for alternatives for transport once discharged from the acute care setting is important. This may determine what services will be necessary and where they will be provided. Will the individual be returning to his or her home environment on discharge from acute care? If so, will he or she require home care or is transportation available for follow-up appointments with physicians and for outpatient rehabilitation? Alternatively, will the individual have an interim stay in another health care facility for further rehabilitation? This information will help set rehabilitation priorities and begin the process of discharge planning.

Health, Emotional, and Cognitive Status

During the interview the rehabilitation professional’s impression of the individual’s general health status that initially developed during chart review broadens. The rehabilitation professional asks questions to discern how the person perceives his or her health and his or her ability to function in self-care, family, or social roles. They assess the individual’s understanding of the current situation and prognosis, as well as expectations about the rehabilitation process. They may explore the person’s coping style and response to stress, as well as preferred coping skills and strategies.27,28 This conversation also provides an indication about the individual’s current emotional status, ability to learn, cognitive ability, and memory functions.

Because rehabilitation involves physical effort, it is important to understand the person with recent amputation’s usual level of activity and fitness, as well as his or her readiness to be involved in exercise. Is physical activity a regular part of the preamputation lifestyle? Has there been a period of prolonged inactivity prior to surgery?29 Will any additional health habits, such as smoking and use of alcohol or other substances, affect the individual’s ability to do physical work and ability to learn or adapt?30

Medical, Surgical, and Family History

Potentially important medical conditions that may influence the postoperative/preprosthetic rehabilitation include diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, obesity, neuropathy, renal disease, congestive heart failure, uncontrolled hypertension, and preexisting neuromuscular or musculoskeletal pathologies or impairments, such as stroke or osteoporosis.31–33 Each of these has a potential impact on wound healing, functional mobility, and exercise tolerance during rehabilitation. Healing and risk of infection are also concerns for those with compromised immune system function, whether from diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), those on transplantation medications, those involved in chemotherapy or recent stem cell transplantation, or those using medical steroids.34 Wound healing, skin condition, and endurance may be issues for persons who are currently undergoing chemotherapy or radiation treatments for cancer.35,36

Review of the individual’s past surgical history provides additional information that helps rehabilitation professionals anticipate what the individual’s response to physical activity might be like. Has the individual had a cardiac pacemaker or defibrillator implanted? Has there been previous amputation of toes or part of the foot of either the newly amputated or “intact” limb? Are there recent surgical scars to be aware of (e.g., following revascularization before amputation)? Has there been total joint replacement or lower extremity fracture that might affect rehabilitation activities and prosthetic component selection?

The “laundry list” of comorbidities and previous surgeries identified in chart review does not necessarily mean that the individual is in poor health.37 Many individuals manage chronic illnesses and conditions quite effectively, and although they may have less functional reserve than those without pathology, they have the potential for positive rehabilitation outcomes.38

Physical therapists must also be aware of the results of tests and diagnostic procedures that other team members have undertaken as part of their examination and evaluation. These might include preoperative cardiac or peripheral vascular studies, electrocardiogram (ECG), stress tests, pulmonary function tests, radiographs, CT, MRI, urinalysis, and laboratory tests for various components of blood (e.g., hemoglobin, cell counts, cultures). Comparison of the individual’s test results to established norms provides an index of overall health status and tolerance of levels of activity. Monitoring laboratory test values (e.g., white blood cell [WBC], hematocrit [HCT], hemoglobin [Hb], platelet, international normalized ratio [INR], partial prothrombin time [PPT], glycosylated hemoglobin [HbA1c], and blood glucose levels) and oxygen saturation levels provide ongoing information about general health status and exercise/activity tolerance, allowing the therapist to adapt intervention to the individual’s potentially changing condition.39,40

Because many of the medications used to manage postoperative pain affect thinking and learning, it is important to understand what pain management strategies are in place and when medication is typically administered.41,42 Given the likelihood of cardiovascular comorbidity in older adults with vascular disease and diabetes, it is also important to understand what cardiac medications are being administered and how these medications affect response to physical activity and position change.43–45 It is not unusual for persons who have been immobile or on bed rest to be at risk of postural (orthostatic) hypotension, especially if they are taking medications to manage hypertension.46 Additionally, given the stress of the surgery and hospital environment, especially if the amputation was performed under general anesthesia, there is the possibility of a temporary postoperative delirium or difficulty with learning and memory.47 If confusion is observed it is important to clarify typical preoperative cognitive status by speaking with family and caregivers.

Current Condition

Review of the operating room report in the medical record provides information about surgical procedure, drain placement, method of closure, and planned postoperative wound and limb-volume strategies being used (Chapter 19 provides an overview of the most common surgical procedures at the transtibial and transfemoral levels). This information, when combined with knowledge of pain management strategies and demographic information, guides early postoperative/preprosthetic care. Physical therapists use this information to identify potential issues with healing, determine educational needs for the person with new amputation, develop strategies for early positioning of the residual limb, identify potential issues affecting prosthetic fit, and prepare the residual limb for wearing a prosthesis. Determining how comorbidities and injuries are being actively managed is also important, as these affect readiness for early mobility, learning, and memory. Impressions of the individual’s psychological state, fears, and expectations round out the baseline with which the person will begin early rehabilitation.

Systems Review

In the acute care setting, there has likely been a fairly comprehensive review of physiological systems as a component of preoperative workup (or emergency care in the case of traumatic injury). Rehabilitation professionals find the results of such review in the physician notes and intake forms in the medical record. The therapist may choose to screen or evaluate in more detail if the information in the record is insufficient in depth or detail as it relates to functional status and response to increasing activity and exercise. Review of systems must include anatomical and physiological status of the cardiovascular, cardiopulmonary, integumentary, musculoskeletal, and neuromuscular systems, as well as communication, affect, cognition, language, and learning style.48

Ongoing screening as rehabilitation progresses will help to identify the onset of secondary problems and postoperative complications that require medical intervention or referral to other members of the team. Deterioration in cognitive status or onset of new confusion over a relatively short period of time is especially important to watch for, as it is often the first indication of dehydration, adverse drug reaction, or infection (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infection, infection of surgical construct) in older adults.49

Test and Measures

In the postoperative, preprosthetic period, physical therapists employ a variety of objective tests and measures to determine the severity of impairment and functional limitation and to establish a baseline that will be used to determine PT movement-related diagnosis, determine prognosis, and assess outcomes of the rehabilitation process.50 Table 20-1 lists examples of tests and measures appropriate for the postoperative, preprosthetic period. Although most strategies are similar to those used in general PT practice, some may need to be adapted to accommodate the condition or length of the residual limb (e.g., the point of application of resistive force during manual muscle testing of knee extension strength after transtibial amputation). Whenever measurement technique is altered, however, the reliability and validity of the data collected may be questionable and the data generated less precise. Therapists often begin with examination at the level of impairment and then move into functional assessment.

Table 20-1

Examples of Tests and Measures Important in the Postoperative-Preprosthetic Period

| Category | Examples of Test or Measurement Strategy |

| Pain | Description of nature or type of pain Visual analog scale for intensity of pain Body chart for location of painful areas Description of factors to increase/decrease discomfort |

| Anthropometric characteristics | Residual limb length Residual limb circumference Description of edema type and location |

| Integumentary integrity | Condition of the incision Nature and extent of drainage Condition of “intact” limb Skin color, turgor, temperature |

| Circulation | Palpation of peripheral pulse Skin temperature |

| Arousal, attention, cognition | Mini-Mental State Examination, Mini-Cog Delirium scales Depression scales (e.g. Geriatric Depression Scale, Centers for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale) |

| Sensory integrity | Protective sensation (Semmes-Weinstein filament) Proprioception and kinesthesia Visual acuity, figure-ground, light/dark accommodation Vestibuloocular function during position change Hearing impairment (acuity, sensitivity to background noise) |

| Aerobic capacity, endurance | Heart rate at rest, % maximal attainable in activity Arm ergometry, single limb bicycle ergometry, combined upper extremity/lower extremity ergometry Respiratory rate at rest, during activity Ratings of perceived exertion or dyspnea |

| Mobility | Observation of bed mobility (e.g., rolling) Observation of transitions (e.g., supine–sit) Observation of description of level of assistance, cueing required transfers (various surfaces, heights) |

| Balance | Static postural control (various functional positions) Anticipatory postural control in functional activity Reaction to perturbation Specific balance tests (e.g., Berg, Functional Reach) |

| Gait and locomotion | Use of assistive devices Level of independence, cuing or assistance required Time and distance parameters (velocity, cadence, stride) Pattern and symmetry Perceived exertion and dyspnea |

| Joint integrity and mobility | Manual examination of ligamentous integrity Documentation of bony deformity |

| Neuromotor function | Observation of quality of motor control in activity Observation of efficiency of motor planning Determination of stage of motor learning with new or adapted tasks Muscle tone Reflex integrity |

| Muscle performance | Strength: manual muscle test, handheld dynamometer Power: isokinetic dynamometer, manual resistance through range at various speeds of contraction Endurance: 10 repetitions maximum, or maximum number contractions, time to fatigue |

| Range of motion/muscle length | Goniometry Functional tests (e.g., Thomas test, straight-leg raise) |

| Self-care and home management | Observation of BADLs and IADLs BADL and IADL rating scales |

Assessing Acute Postoperative Pain

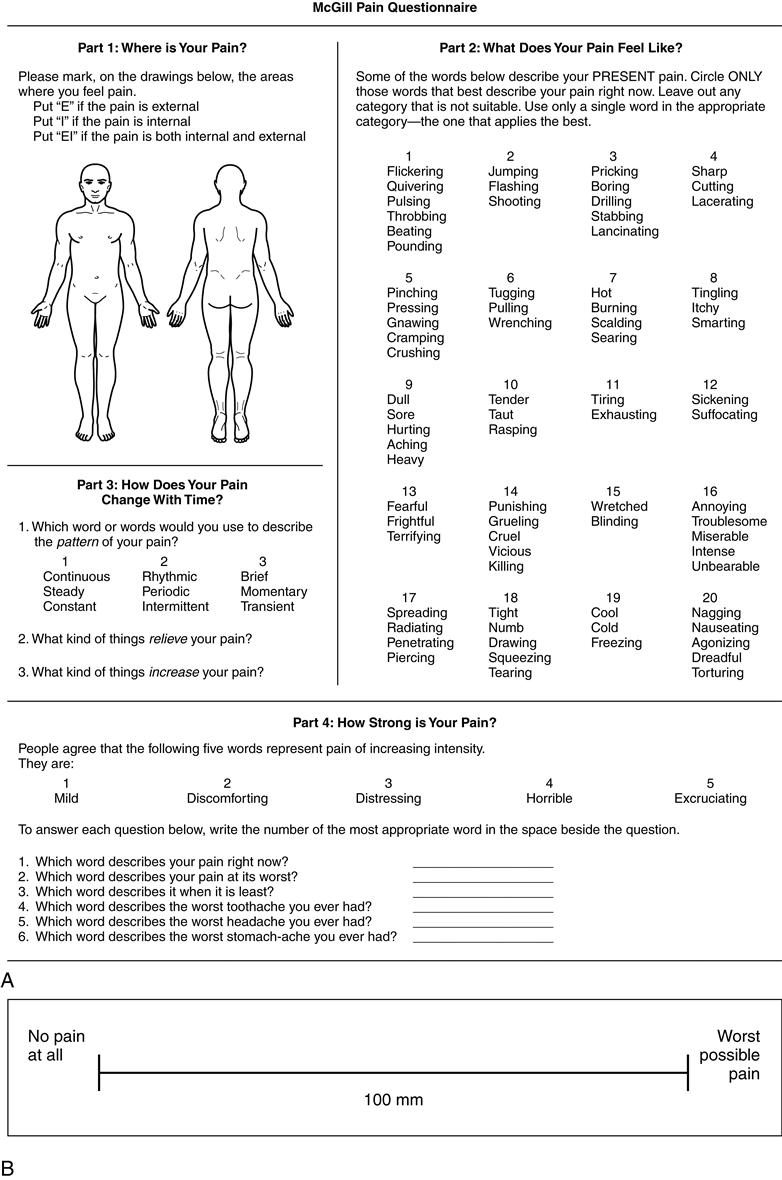

The individual with new amputation is likely to be coping with significant acute postoperative pain and may be distressed by the sense that the limb is still in place (phantom sensation) after amputation. Pain is a subjective sensation; each person defines his or her own level of tolerance. Physical therapists have a number of strategies available to document the nature of pain, location of pain, and the intensity of discomfort that the individual is experiencing. These include descriptors generated by the individual with recent amputation or circled on a pain checklist, body maps, visual analog scales, provocation tests, or specific pain indices or questionnaires developed for postsurgical patients (Figure 20-2).51,52 It is also important to assess how severely that pain interferes with functions, what activities or conditions increase the pain, and what positions or strategies have been helpful in managing the postoperative pain. Documentation of pain management strategies is also important: narcotic and opioid medications potentially impact on attention, ability to learn, and response time during movement and balance activities.53,54

Phantom Sensation and Phantom Pain

Commonly, persons with recent amputation experience a sense that the amputated limb remains in place in the days and weeks after surgery.55 Research reports indicate that from 54% to 99% of persons with new amputation have noticeable phantom limb sensation.56–59 Phantom sensations are typically described as a sense of numbness, tingling, tickling, or pressure in the missing limb, and some complain of itchy toes or mild muscle cramps in the foot or calf.56 In contrast, phantom pain is described as shooting pain, severe cramping, or a distressing burning sensation that may be localized in the amputated foot or present throughout the missing limb. A smaller percentage (46% to 63%) to of those with new amputation experience phantom pain.56–59 Fortunately, fewer than 15% of those experiencing phantom pain rate it as severe or constant; most experience transient mild to moderate discomfort that does not interfere with usual activity. Phantom pain is more likely in those with longstanding and severe preoperative dysvascular pain, and for those requiring amputation after severe traumatic injury.56,59

In most cases, if the individual reports significant phantom sensation or pain, careful inspection of the residual limb helps to rule out other potential sources of pain, such as a neuroma or an inflamed or infected surgical wound. Phantom limb sensation and pain tend to decrease over time whether the amputation was the result of a dysvascular/neuropathic extremity or a traumatic injury.56–59 A variety of medications (e.g., amitriptyline, tramadol, carbamazepine, ketamine, morphine) have can be used if phantom pain is disabling, however efficacy appears to be low.60 Use of epidural anesthesia during surgery and/or perineural infusion of local anesthetic for several days following surgery may help reduce development of phantom pain.61,62 Although a number of models or theories for phantom limb sensation and phantom pain have been proposed, the neurophysiological mechanism that underlies this phenomenon is not well understood.63,64

The likelihood of postoperative phantom limb sensation must be discussed with the individual and family before amputation surgery, as well as in the days immediately after operation. Phantom limb sensation is quite vivid; its realistic qualities can be disturbing and frightening to those with recent amputation. Candid discussion about phantom limb sensation as a normally anticipated occurrence helps to reduce an individual’s anxiety and distress should phantom sensation occur. It also alerts the individual to issues of safety in the immediate postoperative period. Individuals with recent amputation are at significant risk of falling when they awaken from sleep and attempt to stand and walk to the bathroom in the middle of the night, thinking in their semi-alert state that both limbs are intact. Ecchymosis or wound dehiscence sustained during a fall can lead to major delays in rehabilitation and prosthetic fitting; some fall-related injuries require surgical revision or closure.

Assessing Residual Limb Length and Volume

The length and volume of the residual limb are important determinants of readiness for prosthetic use, as well as socket design and components chosen for the training prosthesis.65–67 Initial measurements can be made at the first dressing change. Changes in limb volume are tracked by frequent remeasurement during the preprosthetic period of rehabilitation.

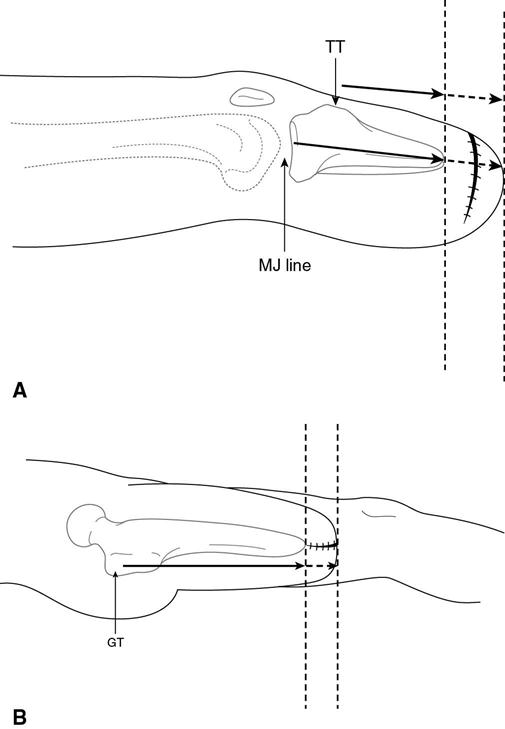

The two components of residual limb length are the actual length of the residual tibia or residual femur and the total length of the limb including soft tissue. Measurements are taken from an easily identified bony landmark to the palpated end of the long bone, the incision line, or the end of soft tissue. In the transtibial limb the starting place for measurement is most often the medial joint line of the knee; an alternative is to begin measurement at the tibial tubercle (Figure 20-3, A). In the transfemoral limb the starting place for measurement can be the ischial tuberosity or the greater trochanter (Figure 20-3, B). Clear notation must be made about the proximal and distal landmarks that are used for the initial measurement to ensure consistency in the subsequent measurement process. Table 20-2 presents a descriptive classification schema for residual limb lengths.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree