Posterior Shoulder Stabilization

Brian T. Feeley

Benjamin C. Ma

INTRODUCTION

Recurrent glenohumeral posterior instability is significantly less common than its anterior counterpart. In most large series, recurrent posterior instability accounts for between 3% and 10% of all patients with glenohumeral instability (6,7). In many cases of posterior instability, there is often a component of inferior laxity or multidirectional instability. The etiology of recurrent posterior instability can be from a single isolated traumatic event, repeated microtrauma (such as occurs with offensive linemen), or atraumatic and associated with ligamentous laxity. Anatomic considerations for posterior instability include soft tissue abnormalities such as a thin or patulous posterior capsule, increased glenoid retroversion, and increased humeral retroversion.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Posterior stabilization is indicated in the younger patient with isolated posterior instability following a trial of physical therapy that has not relieved the feelings of pain and instability. The patient should not have global instability and should have a history of an identifiable traumatic event or recurrent lesser traumatic events. Excessive glenoid retroversion is not a contraindication but should be evaluated properly as it will alter the intraoperative plan considerably. Patients with multidirectional instability are generally not considered candidates for surgery, although those who have failed physical therapy and continue to have primarily posterior-inferior instability may benefit from a posterior capsular shift. The decision on whether to perform an open or arthroscopic posterior stabilization is usually determined based on the need to perform a capsular plication. Those patients who require an isolated labral repair are better managed with an arthroscopic posterior stabilization. Patients who have failed arthroscopic management, patients who have excessive posterior laxity on exam, and those with poor capsular tissue when evaluated arthroscopically should be considered for open posterior stabilization. Patients who voluntarily sublux their shoulder posteriorly with their arm at their side by selective muscle activation should not undergo posterior stabilization. Patients with a psychiatric history, active infection, inability to comply with postoperative immobilization and therapy, and secondary gain are not candidates for surgery.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A thorough history and physical exam is important in the evaluation of suspected posterior instability. Patients typically have a traumatic event where the arm was positioned below shoulder level. There is often a posteriorly directed blow to an arm extended or flexed at the elbow. Other patients report repeated minor traumatic events with the arm positioned in a similar manner. Unlike anterior instability where the primary concern is usually apprehension, patients with posterior instability often present with vague activity-related posterior shoulder pain, clicking, or popping.

Patients often complain of difficulty pushing open heavy doors. The physical exam should document range of motion and must include a complete instability exam. It is vitally important to determine if the posterior instability is isolated or due to a more global instability pattern. Care must be taken to attempt to elucidate signs of multidirectional instability and generalized laxity. Patients with hyperflexibility of the elbows, wrists, and laxity of the contralateral shoulder should raise the possibility of global laxity, and any surgical procedure should commence only after a complete trial of physical therapy has failed.

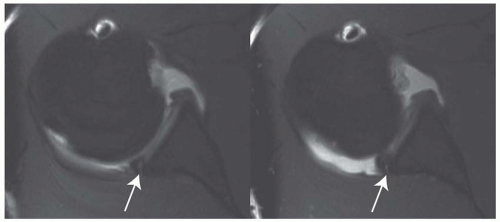

FIGURE 10.2 T1 FSE sequential axial MRI images with contrast of a posterior labral tear (arrows) in a patient with recurrent posterior instability. |

Isolated posterior instability can be elicited in the office setting. The load and shift test is performed by flexing the arm to 90 degrees, flexing the elbow to 90 degrees, and applying a posterior-directed force while stabilizing the scapula with the other hand. The patient may complain of pain or subluxation may be evident on exam. The “jerk test” is performed with an axial posterior load onto an arm flexed at 90 degrees, adducted, and internally rotated; it is positive with reproduction of the instability sensation (Fig. 10.1). It is important to confirm with the patient that the pain felt during this exam is indeed the same pain that is limiting activities as athletes often have multiple causes of shoulder pain. If the load and shift exam does not reproduce the pain experienced by the patient, alternative sources of pathology should be thoroughly explored.

Imaging of the shoulder begins with radiographs. An instability series should be obtained, including an AP of the glenohumeral joint in internal rotation, a West Point axillary view, and a scapular Y view. Plain radiographs are usually normal, but can identify a reverse Hill Sachs lesion and can identify bone loss in the posterior glenoid. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is routinely performed at our institution with the addition of an arthrogram to better delineate any labral pathology (Fig. 10.2). The MR arthrogram is also helpful to determine the capsular volume and can aid in the diagnosis of multidirectional instability. In cases of suspected bone loss or bony abnormalities, a computerized tomography scan with reconstructions is quite beneficial in surgical planning.

SURGERY

Most of the patients receive an interscalene nerve block and general anesthesia. The interscalene block is helpful in limiting intraoperative narcotics and decreases postoperative pain and nausea. The open approach to the posterior shoulder can be performed in either the lateral decubitus position or the beach chair position, but we generally perform this procedure in the beach chair position.

Anesthesia and Positioning

The patient is anesthetized supine on a full-length bean bag and the operating table is configured into the beach chair position. Once the patient is properly positioned, the bean bag is inflated to secure the patient in the upright position. The bean bag must be properly folded to leave the entire medial border of the scapula free.

This setup allows excellent control of the head and body during the procedure and is easy to adapt for people of any body habitus. Once the beanbag is inflated, the patient and beanbag are brought laterally to the edge of the bed, allowing complete exposure of the shoulder to the medial border of the scapula (Fig. 10.3). The arm is prepped and draped in standard fashion. In cases where an open procedure is performed, we routinely use an Ioban dressing in the axilla in order to decrease the risk of p acnes infection. A McConnell arm holder is used to position the arm in space during the procedure.

This setup allows excellent control of the head and body during the procedure and is easy to adapt for people of any body habitus. Once the beanbag is inflated, the patient and beanbag are brought laterally to the edge of the bed, allowing complete exposure of the shoulder to the medial border of the scapula (Fig. 10.3). The arm is prepped and draped in standard fashion. In cases where an open procedure is performed, we routinely use an Ioban dressing in the axilla in order to decrease the risk of p acnes infection. A McConnell arm holder is used to position the arm in space during the procedure.

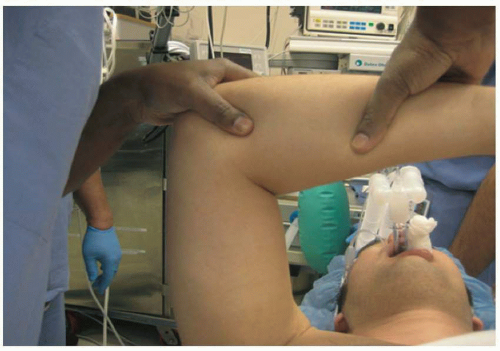

Exam Under Anesthesia

Prior to any incision, it is critical to perform an examination of the shoulder under anesthesia. The examination should be performed on both shoulders to assess asymmetry in the exam compared to the contralateral side. Range of motion should be recorded as well. Exam under anesthesia should confirm grade 2 to 3+ posterior instability without any anterior or inferior translation. In some cases of inferior laxity, however, there will be some degree of inferior subluxation, and this should be accounted for in the capsular placation.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy

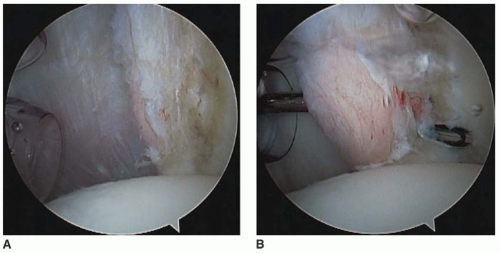

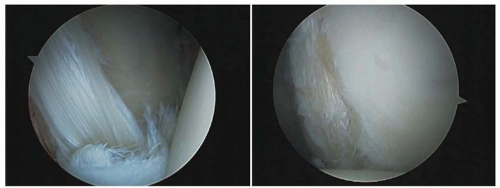

The surface anatomy is marked, with attention paid to the acromioclavicular (AC) joint and the posterior glenohumeral joint. Even in cases where we suspect that an open procedure is necessary, we routinely perform a diagnostic arthroscopy to evaluate the status of the posterior labrum and determine the need to perform a labral repair as well as a capsulorrhaphy. In addition, arthroscopy allows for identification of other concomitant pathology such as biceps tendon lesions, SLAP tears, and articular cartilage injury (Fig. 10.4). After the glenohumeral joint has been evaluated from the posterior portal, the arthroscope is placed in the rotator interval anterior portal to allow for better visualization of the posterior labrum, capsule, and posterior glenoid.

Arthroscopic Posterior Labral Repair

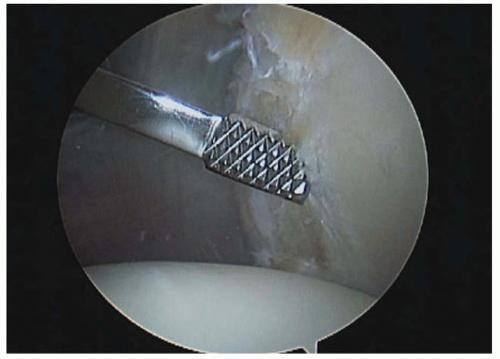

The first step in performing a posterior labral repair is to mobilize the posterior labrum. The arthroscope is kept in the anterior portal and a small rasp elevator is advanced in through the posterior portal. The margins of the tear are identified and the rasp is used to carefully elevate the posterior labrum off the surface of the glenoid (Fig. 10.5). Any bleeding that is encountered is cauterized with an arthroscopic cauterization device. Once the posterior labrum has been completely elevated, a 4.5-mm shaver is used to decorticate the glenoid rim and achieve a fresh bleeding surface.

FIGURE 10.4 Arthroscopic images of a patient with recurrent posterior instability and a posterior labral tear. |

FIGURE 10.5 An arthroscopic rasp is advanced into the joint via the posterior portal. This is used to elevate the posterior labrum off the glenoid neck. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree