Posterior Shoulder Instability Repair

James C. Dreese MD

James P. Bradley MD

History of Arthroscopic Treatment

In comparison to anterior shoulder instability, posterior instability is a relatively rare entity. Most authors agree that posterior shoulder instability represents only 5% to 10% of shoulder instability cases.1,2,3 It encompasses a broad spectrum of pathology ranging from the more common recurrent posterior subluxation (RPS) to the less common locked posterior dislocation (LPD). Consequently, posterior instability may present in a variety of patient populations and clinical scenarios. As a result, confusion has traditionally existed in attempting to diagnose and treat this ill-defined, uncommon entity. Initial attempts in clarifying the distinctions of posterior instability were made in 1962 when McLaughlin1 recognized that differences exist between “fixed and recurrent subluxations of the shoulder,” suggesting that the etiology and treatment of the two are distinctly different. Since that time additional knowledge has been gained in the differences between unidirectional versus multidirectional (MDI), traumatic versus atraumatic, acute versus chronic, and voluntary versus involuntary posterior instability. In many respects each of these may represent a distinct form of posterior instability with its own underlying predispositions, anatomical abnormalities, and treatment algorithms.4,5,6,7,8,9 Our collective understanding of posterior shoulder instability continues to be an evolving process.

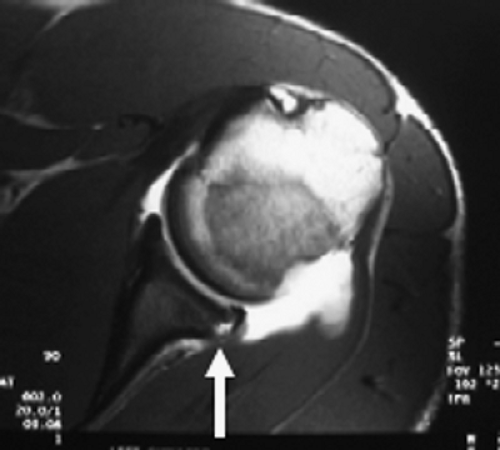

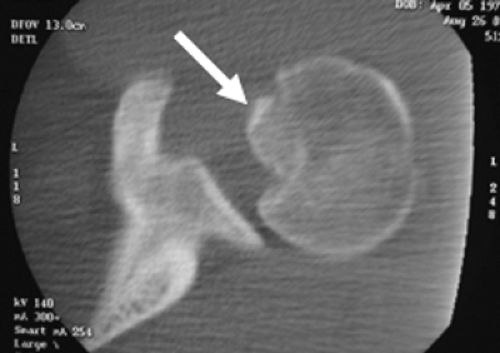

Recent advances in our understanding of the spectrum of posterior instability have been gained through the study of shoulder injuries in athletes, patients with generalized ligamentous laxity, and patients with posttraumatic injuries.4,5,6,7,8,10,11,12 Acute posterior dislocations typically occur as a result of a direct blow to the anterior shoulder or indirect forces that couple shoulder flexion, internal rotation, and adduction.6 The most common indirect causes are accidental electric shock and convulsive seizures. Chronic LPD presents with the humeral head locked over the posterior glenoid rim. As a result of incomplete radiographic studies and a failure to recognize the posterior shoulder prominence and mechanical block to external rotation, 60% to 80% of LPD cases are overlooked by the treating physician. These patients are often given a diagnosis of “frozen shoulder” but fail to improve their external rotation with physical therapy. Patients with both acute posterior dislocations and LPD may suffer a significant osseous defect to the anteromedial humeral head,2 that is often referred to as the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (Fig. 5-1). In addition, a minority of patients with posterior dislocations will also suffer a posterior capsulolabral detachment, often referred to as a reverse Bankart tear (Fig. 5-2). Failure to recognize a posterior shoulder dislocation in the acute period complicates treatment and leads to a predictably poorer prognosis.

In contrast to posterior shoulder dislocations, RPS is often the result of chronic repetitive microtrauma to the posterior capsule without a single traumatic antecedent event. Gradually the patient develops insidious pain with laxity of the posterior capsule and fatigue of the static and dynamic stabilizers.6 RPS may also result from a traumatic reverse Bankart lesion or as a component of MDI.6,7 The capsulolabral avulsion is seen less commonly in posterior instability than it is in anterior instability.13,14 Other proposed mechanisms of RPS include excessive retroversion of the humeral head, an engaging Hill-Sachs lesion, excessive retroversion of the glenoid, and hypoplasia of the glenoid.2,6,15,16

Many patients with RPS can be managed successfully without surgery. Numerous authors have proposed a period of no less than 6 months of physical therapy prior to considering surgical treatment.7,8,17 Effective rehabilitation includes avoidance of aggravating activities, restoration of a full range of motion, and shoulder strengthening.

Strengthening of the rotator cuff, posterior deltoid, and periscapular musculature are critical. The premise of such directed physical therapy is to enable dynamic muscular stabilizers to offset the deficient static capsulolabral restraints. Response to physical therapy is dependent upon the type of RPS present. While patients with atraumatic MDI have enjoyed encouraging success rates with physical therapy alone, the results have not been as optimistic in patients with recurrent traumatic posterior instability.7,17 Restated, patients with a history of macrotrauma initiating the RPS have poorer success rates with rehabilitation alone than patients with recurrent microtrauma or generalized ligamentous laxity. Subjectively, nearly 70% of patients will improve following an appropriate rehabilitation protocol. Objectively, the recurrent subluxation is generally not eliminated, but the functional disability is diminished enough that it does not prevent activities.18,19 If the disability fails to improve with an extended 6-month period of directed rehabilitation, or in select cases of posterior instability resulting from a macrotraumatic event, surgical intervention should be considered.

Strengthening of the rotator cuff, posterior deltoid, and periscapular musculature are critical. The premise of such directed physical therapy is to enable dynamic muscular stabilizers to offset the deficient static capsulolabral restraints. Response to physical therapy is dependent upon the type of RPS present. While patients with atraumatic MDI have enjoyed encouraging success rates with physical therapy alone, the results have not been as optimistic in patients with recurrent traumatic posterior instability.7,17 Restated, patients with a history of macrotrauma initiating the RPS have poorer success rates with rehabilitation alone than patients with recurrent microtrauma or generalized ligamentous laxity. Subjectively, nearly 70% of patients will improve following an appropriate rehabilitation protocol. Objectively, the recurrent subluxation is generally not eliminated, but the functional disability is diminished enough that it does not prevent activities.18,19 If the disability fails to improve with an extended 6-month period of directed rehabilitation, or in select cases of posterior instability resulting from a macrotraumatic event, surgical intervention should be considered.

Fig. 5-1. Computed tomography scan demonstrating an osseous impression defect, also known as a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion (arrow), in a patient following reduction of a posterior shoulder dislocation. |

The surgical treatment of posterior instability has historically included posterior capsular tightening procedures, osseous reconstructions, and combinations of both. In contrast to the surgical treatment of anterior shoulder instability, surgical results of posterior shoulder instability have in general been less consistent. The laterally based posterior capsular shift, as described by Neer and Foster,20 remains the gold standard in the treatment of RPS. Preliminary results of the capsular shift in 25 patients revealed good to excellent results in nearly 90% of patients21 and longer follow-up studies in 38 patients revealed satisfactory results in 80%.22 Similarly, results of a medially based capsular shift have yielded success rates near 90%.7 However, Tibone and Bradley6 reported 40% failure rates in a group of 40 high-performance athletes after undergoing a medially based capsulorrhaphy. The high rate of failures was attributed to an incomplete correction of ligament laxity and unrecognized MDI. Additional soft tissue tightening procedures have included McGlaughlin’s1 description of subscapularis tendon insertion transposition from the lesser tuberosity to fill the reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, Severin’s23 account of the reverse Putti-Platt procedure to divide and advance the infraspinatus laterally over a capsular plication, Boyd and Sisk’s2 report of rerouting the long head of the biceps to the posterior glenoid rim to function as a sling around the posterolateral humeral head, and the report from Tibone et al.24 on repair of a posterior labral tear with a staple. Osseous reconstructions have included a posterior opening wedge glenoid osteotomy, rotational osteotomy of the proximal humerus, and augmentation of the posterior glenoid with a bone block.25,26,27,28 Because each of these procedures has comparatively proven to be either less effective, less safe, or more technically demanding, the posterior capsular shift remains the gold standard in the treatment of posterior shoulder instability.

In the 1990s preliminary results of arthroscopic techniques in the treatment of RPS began to surface. In 1995, Papendick and Savoie13 reported 95% overall satisfactory results in a group of athletes treated by one of four arthroscopic stabilization procedures. In a follow-up study Savoie and Field11 reported 90% success rates at an average follow-up of 34 months. In 1996, Wolf29 described the use of an arthroscopic suture anchor technique in a series of 17 patients, with successful results in 88%. McIntyre et al.12 reported 25% failure rates following an arthroscopic posterior capsular shift with suture capsulorrhaphies in 20 patients with RPS at a mean follow-up of 31 months.

Further investigation suggested that four of the five failures occurred in patients with a voluntary component to their instability. Antoniou et al.30 reported 85% success rates following arthroscopic suture capsulorrhaphy in a series of 41 patients at an average of 28 months follow-up. Ten patients in this series of Antoniou et al. exhibited MDI and also underwent rotator interval closure at the time of surgery. Wolf and Eakin31 reported a group of 14 patients with unidirectional posterior shoulder instability. Patients with RPS as a result of isolated capsular redundancy were treated with suture capsulorrhaphy alone, and patients with labral detachments were treated with arthroscopic suture anchors. At 33 months average follow-up 12 of 14 patients (86%) had good or excellent results and 9 of 10 patients participating in competitive athletics returned to full activity. Studies by Mair et al.14 and Williams et al.32 have reported minimum 2-year follow-up success rates greater than 90% following use of a bioabsorbable tack to repair a traumatic posterior Bankart lesion. Although these published reports present preliminary results, arthroscopic capsulorrhaphy and labral repair techniques have thus far proven to be effective in the treatment of posterior shoulder instability.

Further investigation suggested that four of the five failures occurred in patients with a voluntary component to their instability. Antoniou et al.30 reported 85% success rates following arthroscopic suture capsulorrhaphy in a series of 41 patients at an average of 28 months follow-up. Ten patients in this series of Antoniou et al. exhibited MDI and also underwent rotator interval closure at the time of surgery. Wolf and Eakin31 reported a group of 14 patients with unidirectional posterior shoulder instability. Patients with RPS as a result of isolated capsular redundancy were treated with suture capsulorrhaphy alone, and patients with labral detachments were treated with arthroscopic suture anchors. At 33 months average follow-up 12 of 14 patients (86%) had good or excellent results and 9 of 10 patients participating in competitive athletics returned to full activity. Studies by Mair et al.14 and Williams et al.32 have reported minimum 2-year follow-up success rates greater than 90% following use of a bioabsorbable tack to repair a traumatic posterior Bankart lesion. Although these published reports present preliminary results, arthroscopic capsulorrhaphy and labral repair techniques have thus far proven to be effective in the treatment of posterior shoulder instability.

Thermal capsulorrhaphy techniques have also been proposed in the treatment of posterior shoulder instability. The technique utilizes either laser or radiofrequency energy to induce thermal damage to the tissue of the redundant posterior capsule.9,33,34,35 The degree of the capsular response has proven to be both time and temperature dependent.

An inflammatory reaction results in response to thermal energy, leading to shortening and denaturation of collagen fibrils. Over a period of at least 3 to 4 months a process of remodeling occurs whereby collagen fibroplasia and capsular thickening lead to reduction of the capsular volume. However, there are limits to the degree that capsular tissue can be shortened before the collagen is significantly weakened and its biomechanical properties are irreparably affected. The thermal energy induces a variable response on the part of the patient. Some patients form abundant scar tissue and exhibit significant reduction in capsular volume, while other patients do not respond to such a favorable extent. In addition, the long-term properties of the thermally modified tissue are unknown. Initial short-term results of thermal capsulorrhaphy in shoulder instability were encouraging with success rates near 90%.36,37,38 More recent studies have not been as encouraging, with failure rates near 40%.39,40 In particular, patients with MDI have shown particularly high failure rates.39,40,41 Consequently, many surgeons have abandoned the use of thermal capsulorrhaphy in the treatment of shoulder instability.

Indications and Contraindications

Patients failing extensive physical therapy protocols should receive surgical consideration. The application of arthroscopic techniques to the treatment of shoulder instability is rapidly expanding. The development of arthroscopic techniques with the use of suture anchors has obviated the need for transglenoid drilling. Interval plication and suture capsulorrhaphy techniques have improved arthroscopic results, making them comparable to open procedures.11,12,14,29,30,32 Advantages of arthroscopic techniques over traditional open techniques include less disruption of normal shoulder anatomy, better visualization of intra-articular landmarks, the ability to perform concomitant anterior and posterior stabilization procedures, and complete visualization of both the intra-articular and subacromial spaces. The surgeon’s transition from open to arthroscopic techniques can be difficult. Arthroscopic techniques require the surgeon be familiar with anchor placement, suture management, and arthroscopic knot tying. A thorough understanding of arthroscopic anatomy is vital to the success of arthroscopic stabilization procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree