CHAPTER 24 ![]() Posterior instability: clinical history, examination, and surgical decision making

Posterior instability: clinical history, examination, and surgical decision making

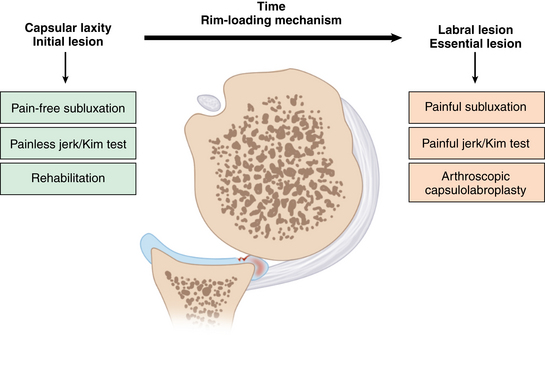

Shoulders with initially asymptomatic hyperlaxity can develop posterior and posteroinferior labral lesion over time by repetitive rim-loading mechanism.

Shoulders with initially asymptomatic hyperlaxity can develop posterior and posteroinferior labral lesion over time by repetitive rim-loading mechanism. An examination should include not only laxity tests but also specific instability tests of the shoulder.

An examination should include not only laxity tests but also specific instability tests of the shoulder. Pain is a typical primary complaint of posterior shoulder instability (unlike anterior instability in which instability is the primary complaint).

Pain is a typical primary complaint of posterior shoulder instability (unlike anterior instability in which instability is the primary complaint). A positive result in the jerk or Kim test is defined as having painful clunk and is sensitive in detecting labral lesion of posterior instability, while painless clunk simply suggests hyperlaxity with intact labrum.

A positive result in the jerk or Kim test is defined as having painful clunk and is sensitive in detecting labral lesion of posterior instability, while painless clunk simply suggests hyperlaxity with intact labrum. A positive jerk or Kim test suggests failure of nonoperative treatment and is an indication of early operative treatment.

A positive jerk or Kim test suggests failure of nonoperative treatment and is an indication of early operative treatment.Anatomy and biomechanics

Traumatic posterior instability develops a distinct posterior labral tear that is potentially identical to the lesion in the traumatic anterior shoulder instability. The labrum is detached from the glenoid, which is the so-called reverse Bankart lesion. However, the reverse Bankart lesion is generally undisplaced or minimally displaced from the glenoid margin, while the anterior Bankart lesion is displaced medially. Often, the anterosuperior aspect of the humeral head has a reverse Hill-Sachs lesion, which is also relatively indistinct compared with the true Hill-Sachs lesion in traumatic anterior instability. Usually, there are indentations or superficial scuffing of the articular cartilage of the anterosuperior aspect of the humeral head.

Atraumatic posterior instability has been controversial in terms of pathogenesis. Several anatomic structures have been implicated, including bony and soft tissue abnormalities. Bony abnormalities include increased humeral retroversion, glenoid retroversion, and glenoid hypoplasia. Anatomic studies revealed that a normal bony retroversion angle is about −4 degrees. Weishaupt et al1 demonstrated that all patients with posterior recurrent shoulder instability had a retroverted glenoid (mean, 7.8 degrees; range, 3 degrees to 21.4 degrees). Previous studies on the glenoid version have been focused on the bony glenoid measured on computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or plain radiographs. However, the stability of the glenohumeral joint is an integral function of both bone and soft tissue stabilizers. The increased cartilage thickness in the periphery and the glenoid labrum contributes to the stability of the joint by increasing the concavity of the glenoid. Lazarus et al2 showed a 65% decrease in the mechanical stability ratio associated with the creation of an anteroinferior chondrolabral defect, an 80% reduction in the height of the glenoid. Accordingly, the measurement of the glenoid version can be more ideal when the articular cartilage and labrum are considered as a whole.

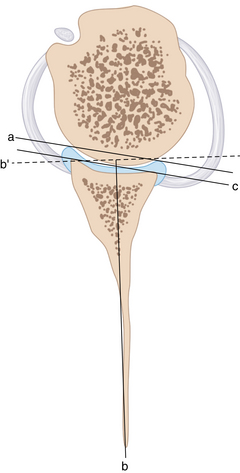

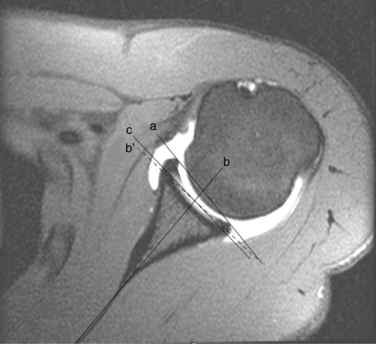

Kim et al3 emphasized that loss of chondrolabral containment is a consistent finding in shoulders with symptomatic posterior instability. They evaluated four measurements that represent glenohumeral containment (bony and chondrolabral glenoid version, labral height, and glenoid depth) on T2 axial images of the magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA) of 33 shoulders with atraumatic posteroinferior multidirectional instability.3 The measurements were compared with 33 age-matched control patients without glenohumeral pathology. The angle of version of the bony and chondrolabral glenoid was measured in three consecutive planes (upper 25%, middle 50%, and lower 75% from upper limb of the glenoid) perpendicular to the long axis of the glenoid. Although the posteroinferior instability group had greater retroversion in both bony and chondrolabral glenoid in the middle and lower planes, the chondrolabral glenoid had more retroversion than the bony glenoid in the lower plane. The height of the posterior labrum was decreased in the lower plane of the instability group. Glenoid depth in the middle and lower plane was significantly shallower in the instability group. Therefore, loss of containment in the middle and lower parts of the chondrolabral glenoid is a consistent finding in shoulders with atraumatic posteroinferior instability and is principally due to the loss of posterior labral height (Figs. 24-1 and 24-2).3 (Video 24-1)

Kim et al3,4 suggest that the loss of chondrolabral containment is a result of cumulative microtrauma to the posteroinferior glenoid labrum, which initially has normal height and undergoes gradual change to retroversion by the rim-loading mechanism (Fig. 24-3). With the loss of chondrolabral containment, the static restraint loses its function and the dynamic stabilizer of the shoulder becomes less effective in maintaining concavity-compression of the glenohumeral joint.

Bradley et al5 similarly measured the posteroinferior chondrolabral version and bony glenoid version for each MRI at the inferior one third of the glenoid rim. In this study, there was increased bony and chondrolabral retroversion in the symptomatic group, which suggests that loss of anatomic containment predisposes to posterior instability.

Soft tissue abnormalities include insufficiency of rotator interval tissue, such as coracohumeral and superior glenohumeral ligaments, and posterior inferior capsular mechanism.6 Generally, the consensus in the pathogenesis of atraumatic posterior instability is an excessive capsular laxity. However, increased capsular ligamentous laxity alone cannot entirely explain the whole pathogenesis of posterior instability, which often occurs in the midrange of motion where normally the capsular ligaments become loose. A recent study demonstrates that the rotator interval is well preserved in all instability patterns and control conditions.7 Other static and dynamic restraints of the glenohumeral joint may provide more important roles in maintaining stability in atraumatic posterior and posteroinferior multidirectional instability. These are concavity-compression provided by muscular force and geometric conformity of the glenohumeral joint, which are mainly provided by articular cartilage and labrum. A thicker periphery and thinner central part of the glenoid articular cartilage form a conforming ball and socket joint together with a thinner periphery and thicker central part in the humeral head articular cartilage. Glenoid labrum further reinforces glenohumeral conformity by doubling the depth of the glenoid socket. Any alteration in this chondrolabral integrity of the posteroinferior aspect can disrupt joint conformity, which will facilitate the posterior instability.2 In the author’s measurement, loss of containment by the retroversion of the chondrolabral glenoid partially explains the potential pathogenesis of the posterior istability.3

Although those who have posterior instability may be either symptomatic or asymptomatic, it is interesting to know that the amount of increased translation either in a posterior, inferior, or anterior direction is the same. Moreover, asymptomatic people often become symptomatic over time. In addition, although the shoulder is loose in all three directions, concurrent production of symptoms is in one or multiple directions. Evidence shows that the amount of translation is not fundamentally different between healthy subjects who have asymptomatic laxity and those who need surgical intervention.8,9 Given these facts, there may be other pathology that is responsible for the shoulder symptom, rather than just an increased joint volume. The author found that the majority of patients with an asymptomatic jerk test in posterior instability, which was represented by a painless posterior clunk, were successful with nonoperative treatment. However, patients with a symptomatic jerk test, which was represented by sharp pain with a posterior clunk, did not respond with the rehabilitation and invariably had a posteroinferior labral lesion in the arthroscopic finding.10 The author concluded that the jerk test was a hallmark for predicting the failure of nonoperative treatment in the posteroinferior instability, and shoulders with a painful jerk test have a posteroinferior labral lesion.10

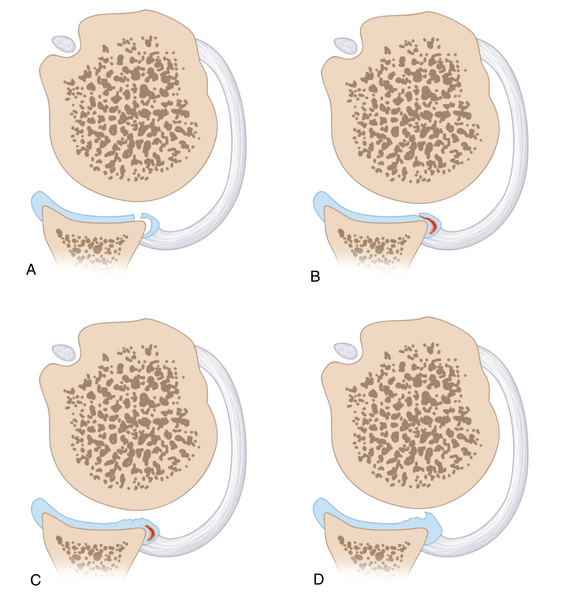

Interestingly, the incidence of labral lesions in posterior instability varies depending on the authors. Compared with articles reporting open inferior capsular shift, literature advocating arthroscopic procedures reported more common incidence of labral lesions and capsular redundancy. Perhaps, arthroscopic examination ensured a more thorough evaluation of the labral lesions, and arthroscopic magnification allowed the detection of more subtle lesions. Of 100 shoulders, Bradley et al5 reported that 43 (43%) had a patulous capsule with no evidence of any labral detachment. Twenty-seven (27%) had an incomplete labral tear, and 30 shoulders (30%) had a complete detachment of the posterior labrum. Kim et al4,11,12 previously reported that all patients who underwent arthroscopic surgery for posterior instability had variable degrees of labral lesions in the posterior and inferior portions of the glenoid. These labral lesions were classified into four types. A type I labral lesion is an incomplete detachment in which the posteroinferior labrum is separated from the glenoid margin but is not medially displaced. This type is more common in traumatic posterior instability than multidirectional instability. A type II lesion is a marginal crack, the so-called Kim lesion, which is an incomplete and concealed avulsion of posteroinferior labrum. A type III lesion is a chondrolabral erosion, and a type IV lesion is a flap tear of the labrum (Figs. 24-4 and 24-5).4,11,12

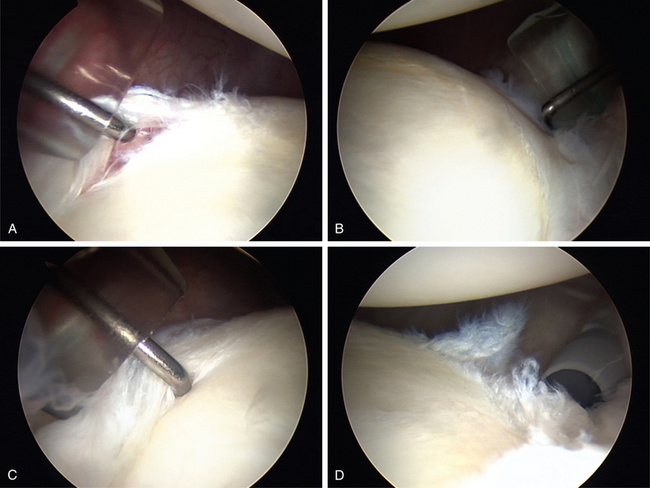

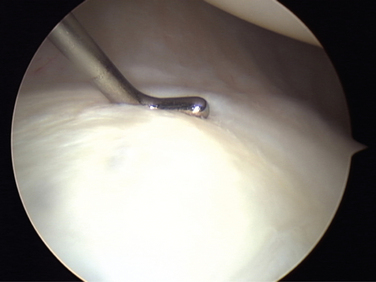

The Kim lesion refers to a superficial tearing between the posteroinferior labrum and the glenoid articular cartilage without a complete detachment of the labrum (marginal crack). The posteroinferior labrum lost its normal height and became a flat labrum, with subsequent retroversion of the chondrolabral glenoid. Probing the lesion demonstrates fluctuation of the posteroinferior labrum and reveals a loose attachment (Fig. 24-6). These labral lesions are limited to the posteroinferior quadrant of the glenoid for shoulders with a pure posterior instability, typically present in 6- to 9-o’clock position for the right shoulder and 3- to 6-o’clock position for the left shoulder. However, the lesion is extended to the entire inferior glenoid labrum from 4 or 5 to 9 o’clock in shoulders with posteroinferior multidirectional instability. When the superficial portion is incised with an arthroscopic knife, for 1 or 2 mm in depth, the lesion reveals detachment in the deep portion of the labrum from the medial surface of the glenoid.4,11,12 (Video 24-2, A-C)

The marginal crack in posteroinferior instability is different from similar lesions, which are often incidentally found in other conditions, such as degenerative arthritis or rotator cuff disease. Therefore, the marginal crack itself is not a hallmark of posteroinferior instability. Symptomatic posterior and inferior subluxations with a positive jerk test (painful clunk) together make the true diagnosis of posteroinferior instability.

Pearls on Biomechanics of Posterior Shoulder Instability

Capsular laxity versus rim-loading mechanism as a pain generator

It is believed that increased translation by the increased capsular laxity is the initial lesion and underlying pathology of posterior and posteroinferior multidirectional instability. This increased capsular laxity can be in-borne or developmental and asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic initially. In this stage, attempted translation does not produce symptoms. Also, jerk and Kim tests reveal posterior clunk without shoulder pain.10,13

However, repetitive subluxations over time overload the posteroinferior glenoid labrum by the excessive rim-loading of the humeral head. This excessive rim-loading eventually develops posteroinferior labral lesions, varying from simple retroversion to incomplete detachment. In this stage, the patient’s symptom, which is shoulder pain, originates from the labral lesion when the humeral head glides over the pathologic labrum. The compressive force on the torn labrum in the jerk and Kim tests generates shoulder pain.10,13 The labral lesion is now the essential lesion responsible for the true shoulder symptom of the posterior and posteroinferior instability. Therefore, intact labrum does not produce shoulder pain no matter how lax the glenohumeral joint is. Increased translation alone produces asymptomatic posterior clunk until the repetitive rim-loading eventually develops a posteroinferior labral lesion (Fig. 24-7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree