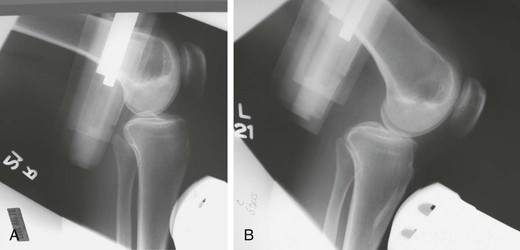

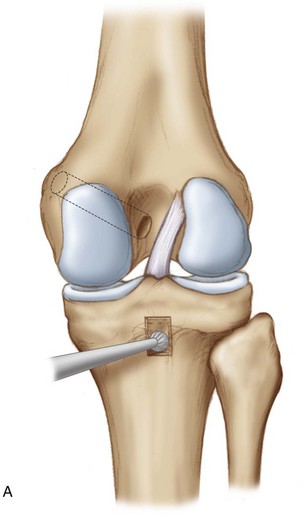

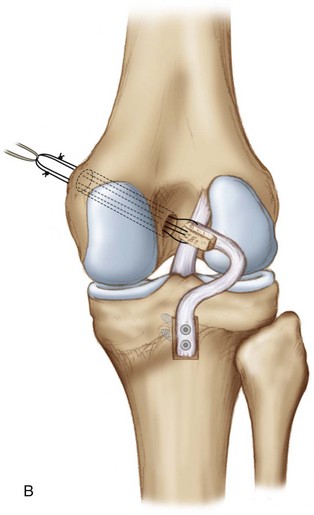

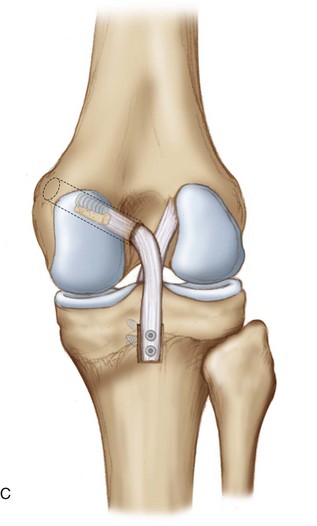

Chapter 82 Ruptures of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) occur more commonly in multiligamentous knee trauma than as isolated injuries. Because this ligament is damaged much less frequently than its counterpart, the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), knowledge of and experience in evaluation and management of the PCL still lag behind those of the ACL. Left untreated, the PCL-deficient knee encounters altered kinematics during weight-bearing activities relative to the uninjured knee, because the PCL is the primary restraint to posterior tibial translation at 90 degrees of knee flexion.1 Accurate, early diagnosis leads to appropriate treatment of PCL injuries. Clinical examination emphasizes the posterior drawer test for evaluation of PCL stability; however, further assessment of posterior tibial subluxation with Telos stress radiography offers more objective evidence of PCL laxity, particularly when compared with the contralateral knee2 (Fig. 82-1). Posterior tibial translation exceeding 10 mm on stress radiography indicates complete PCL rupture, and translation exceeding 12 mm suggests combined PCL and posterolateral corner (PLC) injury. Other physical examination maneuvers include the reverse pivot shift, quadriceps sag, and quadriceps active test. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays a significant role in confirmation of PCL injury and can certainly detect other ligamentous and soft tissue injuries (Fig. 82-2). The optimal method for PCL reconstruction (i.e., transtibial versus tibial inlay; single-bundle versus double-bundle; tunnel positioning) continues to be hotly debated. The goal of this chapter is to detail the operative technique of single-bundle PCL tibial inlay reconstruction, paying close attention to the anatomy and biomechanics of this method. The PCL is an intra-articular ligament that is divided into two bundles based on function in flexion and extension: anterolateral (AL) and posteromedial (PM) (Fig. 82-3). The AL bundle is taut in 90 degrees of flexion and more lax in extension. Conversely, the PM bundle is taut in extension and lax in flexion. Studies show that they appear to have a synergistic relationship for maintaining knee stability.1 The PCL is 32 to 38 mm long and has an average width of 11 to 13 mm.1,3 The proximal and distal bony insertions have two to three times the width of the midportion of the ligament. The PCL attaches to the posterolateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle approximately 10 mm from the articular cartilage, as referenced from a line parallel to the Blumensaat line, and passes in a posterior and lateral direction to attach into a depression on the posterior aspect of the tibia known as the posterior intercondylar facet.1 The attachment on the posterior tibia is bordered by a medial and lateral prominence and is 1.0 to 1.5 cm distal to the joint line.3 The meniscofemoral ligaments of Humphrey and Wrisberg run anterior and posterior to the PCL, respectively, and are secondary stabilizers to posterior tibial translation.1 The presentation is much less dramatic than that of ACL injuries, and large hemarthroses are less common in PCL injuries. Isolated PCL injuries are frequently grade I or grade II and can be treated nonoperatively. The emphasis for physical therapy in nonoperative management is to obtain full range of motion and to rehabilitate the quadriceps mechanism to counteract posterior tibial subluxation. Quadriceps strengthening is often done with exercises in the prone position. These lower-grade PCL injuries may actually demonstrate “healing” on MRI, with collagen remodeling within the ligament. Because the strength of this “healed” PCL is less than that of a native PCL, persistent ligamentous laxity is common.4,5 Nonetheless, isolated low-grade PCL injuries can be treated without surgery. There are several conventional techniques for PCL reconstruction, and newer methods such as computer-assisted ligament reconstruction demonstrate similar outcomes to these conventional approaches.6 This chapter focuses on the operative treatment of the PCL with a single-bundle tibial inlay technique with bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) autograft. This technique is called the inlay because the bone from the BPTB graft is placed into a trough in the posterior aspect of the tibia at the PCL footprint. A significant advantage of the posterior approach and PCL tibial inlay technique is the avoidance of the “killer turn,” which is the acute angulation of the PCL graft that is seen in transtibial PCL reconstructions. This reduces the stress placed across the graft and decreases the potential risk of abrasion and rupture of the graft.7,8 The single-bundle technique detailed in the next section reliably reconstructs the AL bundle of the PCL in its anatomic insertion site (Fig. 82-4).

Posterior Cruciate Ligament Tibial Inlay

Preoperative Considerations

History, Examination, and Indications

Surgical Technique

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Musculoskeletal Key

Fastest Musculoskeletal Insight Engine