Posterior Cervical Approach

Raj Rao

Satyajit V. Marawar

ANATOMY

Posterior Cervical Musculature

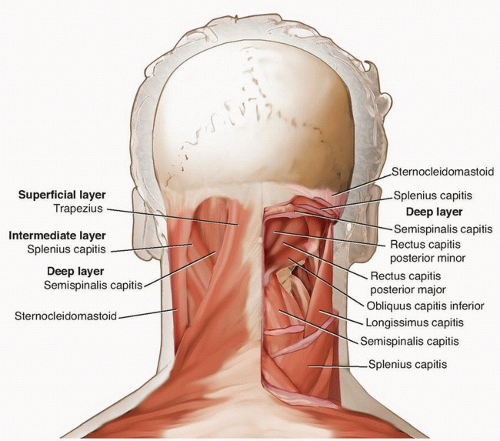

The muscles covering the posterior aspect of the cervical spine are arranged in three layers (FIG 1).

Superficial layer: The trapezius muscle originates from the superior nuchal line of the occiput, the ligamentum nuchae, and the spinous processes of the upper thoracic spine. It inserts into the spine of the scapula and the acromion.

Intermediate layer: The splenius capitis arises from the lower half of the ligamentum nuchae and upper six thoracic vertebrae, inserting onto the mastoid process and the lateral half of the superficial nuchal line under the sternocleidomastoid.

The deep layer consists of the semispinalis capitis, the semispinalis cervicis, the multifidus, and the rotators, arranged from superficial to deep layers, respectively.

The semispinalis capitis arises from the transverse processes of the upper six thoracic vertebrae and the articular processes of the midcervical vertebrae and inserts onto the occiput between the superior and inferior nuchal lines.

The semispinalis cervicis arises from the transverse processes of the upper six thoracic vertebrae and inserts onto the spinous processes of C2-C5.

The multifidus muscle lies deep to the semispinalis cervicis. It originates from the articular processes of the lower cervical vertebrae and inserts onto the spinous processes of the upper cervical vertebrae.

The rotators lie deep to the multifidus. They originate from the transverse process of one vertebra and ascend obliquely to insert on the spinous process of the vertebra one or two levels cranial to their origin.

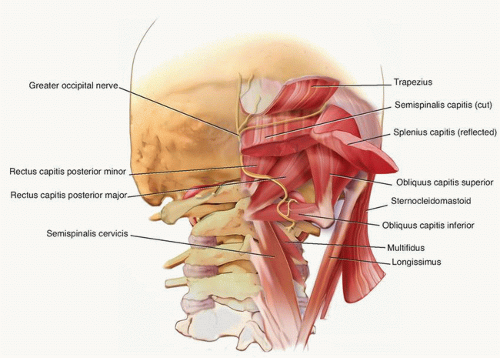

Suboccipital Musculature

The rectus capitis posterior minor originates from the posterior tubercle of the atlas and inserts onto the medial half of the inferior nuchal line.

The rectus capitis posterior major originates from the spinous process of the axis and inserts onto the lateral half of the inferior nuchal line.

The obliquus capitis superior originates from the transverse process of the atlas and inserts onto the occiput laterally between the superior and inferior nuchal lines.

The obliquus capitis inferior muscle originates from the spinous process of the axis and inserts onto the transverse process of the atlas.

The suboccipital triangle lies between the rectus capitis posterior major and the superior and the inferior obliques.

The greater occipital nerve is the medial branch of the posterior division of the second cervical nerve at the medial angle of the suboccipital triangle. It runs cephalad between the semispinalis capitis and the obliquus inferior toward the occiput where it pierces the semispinalis capitis and the trapezius. It is responsible for cutaneous innervation of the back of the scalp (FIG 2).

Osteoligamentous Anatomy

The external occipital protuberance or inion is an easily palpable bony landmark in the midportion of the occiput. The superior nuchal line extends as a bony ridge on either side of this prominence. A small ridge or crest, called the median nuchal line, descends in the medial plane from the external occipital protuberance to the foramen magnum. The inferior nuchal line runs parallel to the superior nuchal line, midway between the inion and foramen magnum (FIG 3).

The atlas does not have a spinous process but has a posterior tubercle marking the center of the posterior arch.

The spinous process of the axis is tall, bifid, and broadest in the cervical spine.

A broad sheet of thick fibrous tissue called the posterior atlanto-occipital membrane extends from the posterior border of the foramen magnum to the superior border of the posterior arch of the atlas.

The posterior atlantoaxial membrane is a broad, thin membrane extending from the inferior border of the posterior arch of the atlas to the superior border of the lamina of the axis.

The tectorial membrane is the cranial extension of the posterior longitudinal ligament, running posterior to the transverse ligament to attach onto the anterior border of the foramen magnum.

The anterior atlantoaxial ligament is the continuation of the anterior longitudinal ligament, extending from the inferior border of the anterior arch of the atlas to the front of the body of the axis (FIG 4).

The supraspinous ligament is absent in the cervical spine. Ligamentum nuchae is a midline avascular fibroelastic structure that is composed of dorsal and ventral components. The dorsal component is a median raphe that extends from the spinous process of C7 to the occipital protuberance, whereas the ventral component is a fascial septum that extends anteriorly from the dorsal component to merge with the interspinous ligament. The interspinous ligament in the cervical spine is thin and less developed.

The ligamentum flavum extends from the superior margin of the inferior lamina to anterior surface of the superior lamina. Laterally, it extends to the articular processes. Infolding of the ligamentum flavum with loss of intervertebral disc height due to degenerative changes can contribute to spinal stenosis.

The pars interarticularis or isthmus of C2 is the waist of the posterior arch of C2, connecting the superior and inferior articular processes. The medial margin of the pars interarticularis along the superior border of the C2 lamina is a guide to the medial margin of the C2 pedicle.

The C1-C2 facet joint is oriented largely in the axial plane, whereas the C2-C3 and remaining subaxial cervical facet joints are coronally oriented 45 degrees to the plane of the spine.

The spinous processes from C3 to C6 are small and bifid. The C7 spinous process tends to be straight and long and terminates in a single tubercle. It is usually the longest of the cervical spinous processes.

The laminae in the cervical spine do not override as much as in the thoracic spine. There is a risk of inadvertent penetration of instruments in the spinal canal through the wide interlaminar windows during surgical exposure.

The lateral mass of the cervical spine refers to the lateral column of each vertebral body that includes the superior and inferior articular processes and the transverse foramen on either side.

It offers a secure fixation anchor for screw insertion from C3 to C6, particularly when the spinous process and lamina are fractured or removed.

A faint longitudinal groove marks the separation between the laminae and lateral masses.

The exiting nerve root and posterior portion of the transverse process lie anteriorly to the lateral mass.

The anteroposterior depth of the lateral mass reduces gradually from C3 (about 8.9 mm) to C7 (about 6.4 mm).3

The lateral mass of C7 is elongated superoinferiorly but is thinner in the anteroposterior plane than the other cervical vertebrae.

The pedicles of the cervical vertebrae are smaller than those in the lumbar spine. Imaging studies should be obtained in all patients prior to screw fixation to verify pedicle morphology and rule out congenital anomalies. Pedicle dimensions generally allow for screw fixation at C2 and C7.

The intervertebral foramen in the cervical spine is bound anteriorly by the uncinate process, the intervertebral disc, and the inferior portion of the superior vertebral body; superiorly and inferiorly by the pedicles; and posteriorly by the facet joint and the superior articular facet of the inferior vertebra.

FIG 3 • A. Bony anatomy of the occiput with muscular insertions. Superior, inferior, and median nuchal lines are the prominent bony ridges on the posterior occipital surface. The major posterior cervical muscles and muscles of the suboccipital triangle insert on these bony ridges and on the posterior occipital surface between these ridges. B. Sagittal cross-section showing the ligamentous architecture of the proximal cervical spine. Anterior and posterior atlanto-occipital as well as atlantoaxial ligaments and the ligaments stabilizing the odontoid process are depicted: the apical ligament of the dens and the transverse ligament of the atlas.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|