Plantar Fibromatosis

Michael S. Downey

Randall J. Contento

Plantar fibromatosis is a benign, locally invasive soft tissue tumor characterized by fibroblastic proliferation within the plantar fascia. The fibromatoses can be divided into two major groups: the superficial (fascial) fibromatoses and the deep (musculoaponeurotic) fibromatoses. The superficial (fascial) fibromatoses can be further subdivided into palmar fibromatosis of the hand (Dupuytren contracture), penile fibromatosis (Peyronie disease), fibromatosis of the knuckle pads (Garrod knuckle), and plantar fibromatosis (Ledderhose disease). The deep (musculoaponeurotic) fibromatoses are subdivided into extra-abdominal fibromatosis, abdominal fibromatosis, and intra-abdominal fibromatosis. The deep (musculoaponeurotic) fibromatoses are more locally aggressive than the superficial (fascial) aponeuroses and may be genetically different (1).

In 1743, Francois de la Peyronie, surgeon to Louis XIV of France, was the first to describe a treatment for penile fibromatosis. However, it was not until 1831 when Baron Guillaume Dupuytren, a French anatomist and military surgeon for Napoleon, first noted a nodular thickening of the plantar aponeurosis of the foot. Ultimately though, Dupuytren concentrated his work on the nodular thickening of the palmar fascia of the hand. Many years later in 1894, Georg Ledderhose, a German surgeon, described plantar fibromatosis, and the condition in the foot is now often called Ledderhose disease or Dupuytren disease of the plantar fascia (2). The superficial (fascial) fibromatoses of the hand, penis, foot, and knuckle pads bear many similarities. However, while many diagnostic and therapeutic modalities have been proved successful for one or more of these conditions, they have not been proved successful for all of the others. In this chapter section, these similarities and differences are explored as they relate to the current treatment of plantar fibromatosis.

ETIOLOGY

The exact etiology of plantar fibromas and plantar fibromatosis is unknown. The superficial (fascial) fibromatoses have a documented increased incidence in several disease states and associated exogenous factors. These include diabetes mellitus and hyperglycemia, epilepsy, thyroid and parathyroid dysfunction, gout, rheumatism, neurosyphylis, pulmonary tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, infection, alcoholism, smoking, trauma, keloid formers, working class patients, and low body mass index (1,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 and 19). Many of these comorbidities appear to suggest that trauma might be a causative factor, and Dupuytren felt it was the primary cause (20). Hafner et al (21) concluded that 25% of recalcitrant heel pain is neoplastic in origin and due to plantar fibromas or plantar fibromatosis.

Although in Dupuytren disease of the hand an autosomal dominant inheritance has been demonstrated, familial inheritance of plantar fibromatosis is rare (12,22,23 and 24). de Palma et al (9) conducted an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural comparison of palmar and plantar fibromas and concluded they are different clinical manifestations of the same autosomal dominant disease. One distinction these authors noted is that Dupuytren nodules in the hand often have distal extensions into the fingers causing debilitating contractures. Conversely, there are few reported cases of plantar fibromatosis with extension into the forefoot and toes (18,25).

Plantar fibromatosis is more likely to occur in patients with other superficial (fascial) and deep (musculoaponeurotic) fibromatoses than in the normal population, but the exact incidence or etiology for this has not been determined. Several authors have reported an association between palmar fibromatosis and plantar fibromatosis, with the rates of concomitant disease reported to be between 10% and 65%. When the two conditions occur in the same patient, they are usually metachronous in their development with a 5- to 40-year interval and rarely synchronous (6,26,27,28,29,30,31 and 32).

Another potential etiology is growth factors, such as plateletderived growth factor, transforming growth factor-beta, and free oxidized radicals. These growth factors have been proposed to possibly contribute to the growth of plantar fibromas (7,33,34 and 35). Merlo et al (36) showed increased amounts of plasminogen activator enzymes in large Dupuytren nodules and felt this was a possible predictive marker for recurrence after excision. Pagnotta et al (37) found that the expression of androgen receptors in Dupuytren contracture was considerably higher than in the normal palmar fascia. These authors questioned whether this increase in androgen receptors could account for the higher incidence of Dupuytren contracture in the male sex.

The etiology of plantar fibromatosis is very likely multifactorial including traumatic, genetic, and other causes (38). A good history and review of systems can often elicit potential etiologies for the condition.

INCIDENCE

Plantar fibromas have been reported in children as young as the first year of life and can occasionally present in the child as a fiercely recurrent and debilitating problem. More commonly, the lesions occur in the third to sixth decade of life and form over a variable period of time from 1 month to years. In a large study from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP), 44% of patients were younger than 30 years of age (11).

Although Dupuytren contracture of the hand is much more common in males, a similar sexual predilection has not been conclusively found for plantar fibromatosis (3,6,11,14,26,39). Some authors have reported that plantar fibromatosis is twice as common in men as in women (28,29,30,31 and 32).

Plantar fibromatosis occurs bilaterally in 20% to 50% of patients and the lesions typically develop in a metachronous fashion with a 2- to 7-year interval (28,29,30,31 and 32). Roughly two-thirds of the lesions present as solitary plantar fibromas and one-third as multiple nodules (30,32) (Fig. 95.1).

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

Plantar fibromatosis is less common than palmar fibromatosis with a reported incidence of 0.23% (40). Both palmar and plantar fibromatoses have been reported by Luck (41) to progress through three phases: (a) a proliferative phase with cellular proliferation, increased fibroblastic activity, and minimal collagen deposition; (b) an involutional (active) phase with decreased proliferative activity, increased collagen deposition, and nodule formation; and (c) a residual (end) phase with collagen maturation, minimal cellularity, and tissue contraction. However, unlike Dupuytren contracture of the hand, the lesions of plantar fibromatosis seldom have an inflammatory proliferative phase and often remain asymptomatic throughout their growth (15,42). Plantar fibromas typically present as slowly enlarging, palpable, fixed, firm masses on the plantar aspect of the foot. Plantar fibromatosis typically involves the medial plantar arch with involvement of the medial band, and occasionally the central band, of the plantar fascia. Most commonly, the lesions form at the level of the navicular and the fifth metatarsal where the plantar fascia is the thickest. They can appear as single or multiple nodules, and in more advanced cases, the lesions can invade the overlying skin causing adherence and immobility upon examination (3,4,6,7,13,15,16 and 17,25). The medially located lesions are usually not painful, but can become painful if they put increasing pressure on the underlying branches of the medial plantar nerve. When symptoms occur, they commonly include the feeling of a mass in the foot, difficulty in fitting shoes, and pain and tenderness with weight-bearing. Allen et al (6), in their series, found that the mean size of the nodular, thickened area was 3 cm × 2 cm × 2 cm, while others have described lesion sizes ranging from 0.5 to 10.5 cm. Unlike Dupuytren contracture of the hand, which often involves the fourth and fifth fingers, plantar fibromatosis rarely involves the toes (3,4,6,7,13,15,16 and 17,25).

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

The diagnosis of plantar fibromatosis can often be made clinically and diagnostic imaging studies may be unnecessary. However, if the lesion is not palpably adherent to the plantar fascia, symptomatic, multinodular, or suspicious in any way, advanced diagnostic imaging should be considered.

Plain radiographs will not contribute to the diagnosis of most plantar fibromas, although osseous metaplasia (43), and juvenile calcifying aponeurotic fibromas, also known as Keasbey lesions, have been reported (44). Computed tomography (CT) scans are also of limited value in the evaluation of a plantar fibroma. The CT appearance of a plantar fibroma is as a nonspecific soft tissue mass with attenuation similar to or mildly higher than that of muscle (30,31).

In most cases, ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the preferred modalities for the assessment of suspected plantar fibromatosis as they are helpful in defining the size of the lesion, its soft tissue character, and in planning for its surgical excision, if indicated.

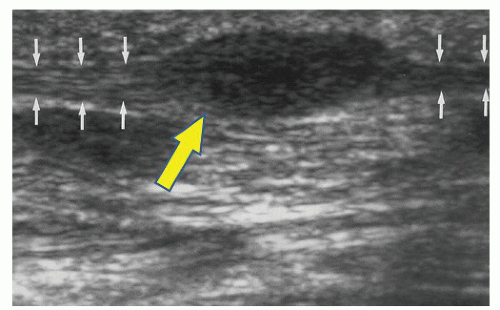

Griffith et al (45) performed sonographic images on 25 plantar fibromas in 19 feet and found that 64% of the lesions were well defined, 76% of the lesions were hypoechoic, and 92% showed no intrinsic vascularity. The images were obtained with the patient lying prone and resting their foot off the edge of the examination table. Similarly in their series, Bedi and Davidson (46) found that 31 of the 43 lesions (72%) they assessed were hypoechoic. They found that lesions longer than 10 mm in size were more likely to have mixed echogenicity. More recently, Haun et al (47) reported performing ultrasonography on a well-circumscribed, subcutaneous mass with heterogenous echogenicity, cystic components, and mild intratumoral hypervascularity. After surgery, a pathologic diagnosis of plantar fibroma with myxoid degeneration and cyst formation was made. Ultrasonography may become the imaging modality of choice for plantar fibromas due to its lower cost and greater availability (48) (Fig. 95.2).

Figure 95.2 Musculoskeletal US image of plantar fibroma. Small arrows point to normal plantar fascia, and large arrow points to the plantar fibroma. |

MRI has long been advocated for evaluating any soft tissue mass. However, with a small plantar fibroma, MRI may not be able to distinguish between the fibroma and the normal plantar fascia due to their similar low signal intensity. In most cases though, MRI will provide well-defined borders, presence of any invasion into intermuscular septa, and insight as to what stage the disease is in. On a T1-weighted image, a plantar fibroma will have low signal intensity with little differentiation from the muscle and fascia around it (Fig. 95.3A). Nodular thickening can be seen. On a T2-weighted image, a fibroma will appear with low to medium intensity depending on the stage of the lesion. On the T2-weighted image, low signal intensity is a sign that there is low cellular activity and the nodule is in the residual or end phase (Fig. 95.3B). The abundance of collagen with few cells produces a low, dark signal. Medium or higher signal intensity may indicate an increase in cellular activity and may have a higher rate of recurrence if excised since the fibroma is in the proliferative or involutional (active) phase (49,50,51,52 and 53) (Fig. 95.3C and D). Morrison et al (49) noted an increase in signal intensity with the administration of gadolinium on T2-weighted images in 9 of 15 lesions. They concluded that the presence of the contrast may help visualization in some cases, but is not necessary to view the dimensions of a plantar fibroma. Murphey et al (38) from the AFIP have described linear tails of extension along the plantar aponeurosis (“fascial tail” sign) that are common and often best seen on postcontrast images. More aggressive plantar fibromatosis may demonstrate both low signal and high signal intensity within the mass. Poor margination, inhomogeneity, and invasion of bone can be seen, and these characteristics make it difficult to distinguish between an aggressive plantar fibromatosis and a malignant tumor on MRI alone (15).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree