CHAPTER 121 Piriformis Syndrome

BACKGROUND

In 1928, Yeoman1 ascribed 36% of cases of sciatica to sacroiliac arthritis transmitted via the piriformis muscle. Later articles by Freiberg and Vinkle in 19342 and by Freiberg3 also supported the notion of sciatica secondary to sacroiliac arthritis and compression by the piriformis muscle and fascia. In 1934, Mixter and Barr4 described the herniated disc as a cause of sciatica, which brought into question the original etiologies of sciatica proposed by Yeoman and Freiberg. Despite this compelling new evidence implicating a herniated disc as a major cause of sciatica, the literature continued to reflect the belief that the piriformis muscle can be involved in the etiology of sciatica. In 1936, Thiele5 described piriformis muscle pain secondary to spasm and hypertrophy irritating the sciatic nerve. In 1936, Shordania6 coined the term ‘piriformitis’ based on his observations of 37 women with sciatica. In 1937 and 1938, Beaton and Anson7 ascribed coccydynia to anatomic variations in the sciatic nerve and piriformis muscle. However, it was Robinson8 who, in 1947, first coined the term ‘piriformis syndrome’ and described six associated typical features. Robinson, like his predecessors, reported that the piriformis muscle and fascial tissues could cause sciatica. Despite this historical evolution of the diagnosis and modern advances in techniques of electrophysiologic testing and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), piriformis syndrome remains a diagnosis of exclusion and is poorly understood and controversial. A recent survey of physiatrists revealed a lack of consensus on whether the diagnosis of piriformis syndrome exists, and if it does exist, how to make the diagnosis.9 Much of the controversy stems from the relative rarity of the diagnosis when compared to the more easily recognized and treatable causes of sciatica stemming from the lumbar spine.10

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Low back pain and sciatica, described as pain or numbness within the buttock and posterior thigh with occasional radiation into the foot, are common complaints, with a reported lifetime incidence as high as 60–90%.11 The total cost of low back pain and sciatica is significant, exceeding US$16 billion in both direct and indirect costs. Given the lack of agreement on exactly how to diagnose piriformis syndrome, estimates of frequency of sciatica caused by piriformis syndrome vary from rare to approximately 6% of sciatica cases seen in a general family practice.12,13 There is no clear age or gender preference, with reports varying from a 6:1 female-to-male predominance, while others suggest a 1.4:1 male-to-female ratio.13,14

ANATOMY

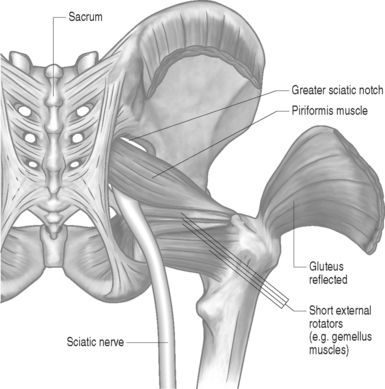

The piriformis muscle is flat, pyramid-shaped, and broadly originates from the ventrolateral surface of the sacrum from the S2–4 vertebrae. The piriformis muscle originates from the anterior surface of the sacrum between and lateral to the anterior sacral foramen, capsule of the sacroiliac articulation, the margin of the greater sciatic foramen, and the sacrotuberous ligament. From its point of origin, it passes through the greater notch and dorsal to the sciatic nerve before inserting on the superior-medial aspect of the greater trochanter of the femur (Fig. 121.1).

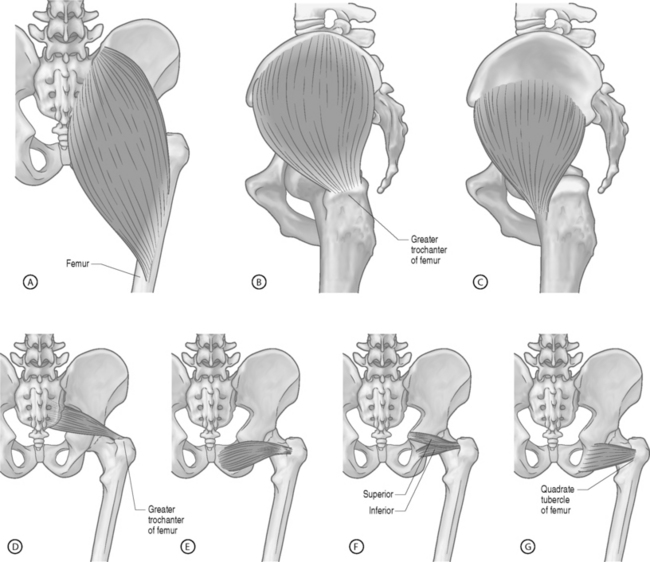

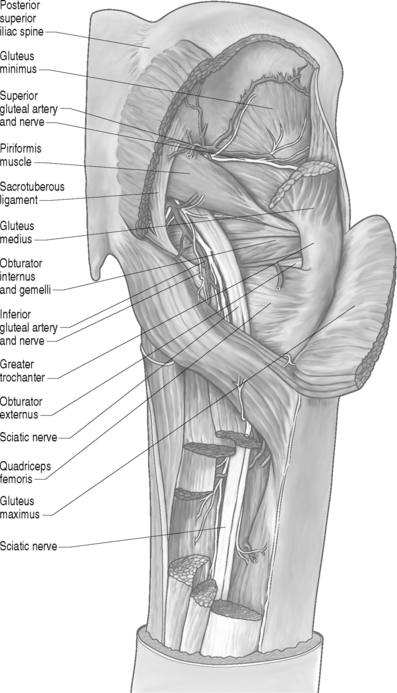

The piriformis muscle is the most proximal of the hip external rotators. With the hip extended, the piriformis muscle externally rotates the hip; however, with the hip flexed, the piriformis muscle becomes a hip abductor.15 Branches from L5, S1, and S2 nerve roots innervate the piriformis muscle. The superior gemellus, inferior gemellus, quadratus femoris, and obturator internus act as synergists with the piriformis muscle (Fig. 121.2, 121.3).

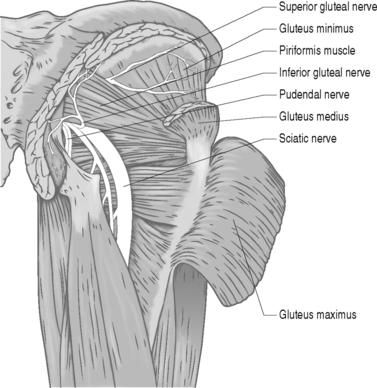

Many developmental variations of the relationship between the sciatic nerve in the pelvis and piriformis muscle have been observed. The sciatic nerve consists of branches from the L3 to S3 nerve roots and usually courses beneath the piriformis muscle and dorsal to the gemellus muscles after exiting the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen (Fig. 121.4).16 In approximately 20% of the population, the piriformis muscle belly is split with one or more parts of the sciatic nerve dividing the muscle belly itself. In 10% of the population, the tibial and peroneal divisions of the sciatic nerve are not enclosed in a sheath. Usually, the peroneal portion splits the piriformis muscle belly, while it is rare for the tibial division to split the piriformis muscle belly.16

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Based on its etiology, piriformis syndrome may be divided into primary or secondary causes (Table 121.1). Primary causes occur from direct nerve compression such as trauma or due to factors that are intrinsic to the piriformis muscle and include anomalous variations in the muscle anatomy, muscle hypertrophy, chronic inflammation of the muscle, and secondary changes from trauma such as adhesions. Secondary causes may include symptoms due to pelvic mass lesions, infections, and anomalous vessels or fibrous bands crossing the nerve, bursitis of the piriformis tendon, sacroiliac inflammation, and possibly myofascial trigger points. Other causes of symptoms may include pseudoaneurysms of the inferior gluteal artery adjacent to the piriformis muscle, bilateral piriformis syndrome due to prolonged sitting during extended procedures, cerebral palsy due to hypertonicity and contractures, total hip arthroplasty as discussed below, and myositis ossificans.

Table 121.1 Primary Versus Secondary Piriformis Syndrome

| Primary | Secondary |

|---|---|

| Trauma | Hematoma |

| Pyomyositis | Bursitis |

| Myositis ossificans | Pseudoaneurysm |

| Dystonia musculorum deformans | Excessive pronation |

| Hypertrophy | Fibrous bands |

| Adhesions | Mass lesions |

| Fibrosis | Anomalous vessels |

| Anatomic variations |

Lumbar hyperlordosis and hip flexion contractures increase piriformis muscle strain and seem to predispose individuals with these to developing symptoms. Altered gait biomechanics has also been theorized to lead to piriformis muscle hypertrophy and chronic inflammation, which can cause piriformis syndrome. Patients with weak abductors or leg-length discrepancies are particularly prone. During the stance phase of gait, the piriformis is stretched as the weight-bearing hip is maintained in internal rotation. As the hip then enters the swing phase, the piriformis muscle contracts, aiding in external rotation. The piriformis muscle is under strain during the entire cycle of gait and may be more prone to hypertrophy than other muscles in that region.10,17–19 Any gait abnormality that maintains the affected hip in a position of increased internal rotation or adduction may increase muscle strain even more.

Blunt injury may cause hematoma formation and subsequent scarring between the sciatic nerve and short external rotators, which may lead to symptoms. In a study of 15 patients with post-traumatic piriformis syndrome as a result of a direct blow to the buttock, all patients had a release of the piriformis tendon and sciatic neurolysis with return to normal activity 2 months after surgery.20

A lower lumbar radiculopathy also may cause secondary irritation of the piriformis muscle, which may complicate the diagnosis and hinder physical treatment methods, as the treatment for a lower lumbar radiculopathy involves stretching of the lower back and hip musculature which may, in fact, increase the symptoms in a patient with piriformis syndrome. Even though there are case reports linking the superior gluteal nerve to piriformis syndrome, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that this nerve is involved in true cases of piriformis syndrome.21 Furthermore, the superior gluteal nerve usually leaves the sciatic nerve trunk and passes through the canal above the piriformis muscle.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

However, piriformis syndrome is often a diagnosis made after excluding other causes of sciatica emanating from the lumbar spine or a pelvic mass causing extrinsic compression of the sciatic nerve. Attempts have been made to derive a set of features that could strongly suggest the diagnosis by history and examination. Robinson was the first to do so when he described six typical features: (1) a history of fall on the buttocks; (2) pain in the sacroiliac joint, greater sciatic notch, and the piriformis; (3) acute exacerbations brought on by stooping or lifting; (4) presence of a palpable mass over the piriformis; (5) positive Laseque’s sign; and (6) gluteal atrophy.8

While there are no pathognomonic tests on physical examination to diagnose piriformis syndrome, there are a number of findings that may aid the diagnosis. In the supine position, the patient may have a tendency to keep the affected leg slightly elevated and externally rotated (positive piriformis sign) (Fig. 121.5).17 Piriformis muscle spasm can be detected by careful deep palpation over the location where the piriformis muscle crosses the sciatic nerve (Fig. 121.6). Locating the midpoint of a straight line drawn between the coccyx and the greater trochanter can approximate this position. Digital rectal examination may reveal tenderness over the lateral pelvic wall that reproduces the syndrome. Reproduction of sciatica-type pain with weakness is noted by resisted abduction/external rotation (Pace test) (Fig. 121.7). The Freiberg test is another diagnostic sign that elicits pain upon forced internal rotation of the extended thigh. Beatty described a technique that attempts to distinguish between lumbar radiculopathy, primary hip disease, and pain caused by piriformis syndrome.22 However, it was noted that the Beatty test can be positive in patients with herniated lumbar discs or hip osteoarthritis and therefore has a low specificity. The patient is made to lie on his or her side with the affected leg facing up and is then asked to hold the affected knee in the air for several minutes. Deep buttock pain was reported to be consistent with piriformis syndrome (Fig. 121.8). A painful point may be palpated at the lateral margin of the sacrum. On occasion, weak abductors or shortening of the involved extremity may be seen. Careful examination of the ipsilateral foot may reveal that the second metatarsal is longer than the first (Morton’s foot) causing a rocking motion during step-off and increased adduction and hip stress. While in the authors’ experience not one of these physical exam maneuvers is pathognomonic, the authors do feel that a combination of positive findings in a patient with the appropriate history and diagnostic work-up is consistent with piriformis syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree