Basic Anatomy and Normal Function

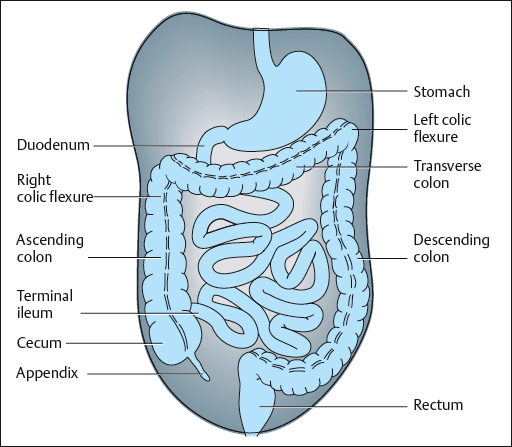

The digestive tract begins at the mouth, continues through the esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines, and finally ends at the rectum and anus. For the purposes of this discussion, we can briefly review the portion of the digestive tract distal to the small intestine.

The final portion of the small intestine, the ileum, empties into the large intestine at the cecum, which is a blind sac continuous with the ascending colon, in the right iliac fossa. This is the location of the vermiform appendix, which

is a narrow portion of the large bowel and contains a considerable amount of lymphatic tissue (Fig. 6.3). An important surface landmark is McBurney’s point, which corresponds to the attachment of the appendix to the cecum. It is situated at the junction of the lateral and middle thirds of a line joining the anterior superior iliac spine and the umbilicus [Thompson 1977].

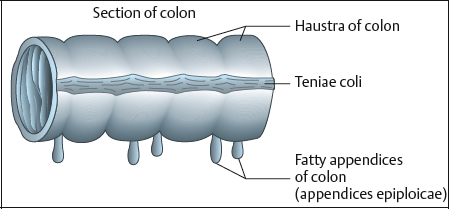

The large intestine has three parallel bands of longitudinal muscle fibers known as the teniae coli, and deeper circular muscle over its whole circumference. In the walls of the colon, there are sacculations known as haustra, and small sacs of fat known as the appendices epiploicae that hang down from the surface of the large intestine (Fig. 6.4). The colon consists of four sections, two of which have mesentery (a double fold of peritoneum that connects an organ to the body wall):

- Ascending colon: no mesentery; ends at the right colic (hepatic) flexure

- Transverse colon: from the right colic flexure to the left colic (splenic) flexure

- Descending colon: no mesentery; begins at the left colic flexure

- Sigmoid colon: folded over on itself in the shape of the letter “S”; empties into the rectum

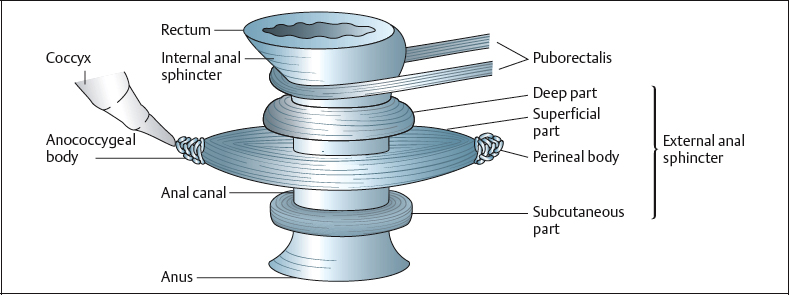

The rectum is about 12 cm long, starting at level S3 and following the curve of the sacrum and coccyx to approximately 2.5cm below the tip of the coccyx, where it turns in a posterior direction to become the anal canal. The normal anorectal angle is between 60° and 105°, influenced by the tonic action of the puborectalis portion of the levator ani muscle (this portion winds from the pubis posteriorly to the junction between the rectum and the anal canal). The rectum has three concavities in which transverse rectal folds partly close the lumen of the rectum. In the rectum and anus, and embedded within the pelvic floor, there are receptors that make it possible to sense the presence of feces and differentiate between matter that is solid, liquid, or gaseous [Kumar 2002].

The anal canal is about 3 cm long, and consists of an internal sphincter and an external sphincter (Fig. 6.5). The internal sphincter is involuntary, and surrounds the upper three-quarters of the anal canal [Fox et al. 1991]. The external sphincter includes voluntary muscle fibers with the same muscle mass as the levator ani, and forms a collar around the entire length of the anal canal. The levator ani muscles give off fibers that course down to and interdigitate with the fibers of the external sphincter.

Both sphincters are innervated primarily by the inferior rectal nerve (S2–S4, pudendal). The sphincter can be subdivided into three portions, all of which operate as a single unit. These are the subcutaneous portion of the sphincter, which lies beneath the perianal skin; the superficial portion, which spans an area from the central perineal tendon to the anococcygeal ligament; and the deep portion, which encircles the internal sphincter.

The upper two-thirds of the anal canal are lined with mucous membrane, and the lower third with skin.

Normal Mechanisms of Continence and Stool Evacuation

Normal Mechanisms of Continence and Stool Evacuation

Continence

Continence

There are two distinct means of maintaining anal continence. The first is termed “resting” continence, and exists when there is no urge to evacuate—i. e., during the normal resting state. This type of continence is highly dependent on the anal sphincter muscle tone [Couturier et al. 1982], which is mainly due to the tonic activity of the (smooth) internal sphincter [Valancogne 1993]. The remainder is dependent on the tonic activity of the slow-twitch fibers of the external anal sphincter, as well as the resting position of the anorectal angle, which is maintained by permanent tonic activity of the puborectalis portion of the levator ani musculature.

By contrast, “active” continence denotes the act of maintaining continence on the urge to evacuate, at the arrival of feces in the rectum. This form of continence is dependent on rectal sensitivity, rectal compliance, and on activity at the anal sphincter and pelvic floor musculature. During active continence, the normal sequence of events is as follows:

- Firstly, the arrival of feces in the rectum distends the rectum, triggering the stretch receptors, rectal contraction, and relaxation at the internal sphincter (the rectoanal inhibitory reflex).

- Secondly, the external sphincter contracts to hold back stool, due to an acquired reflex (the rectosphincteric striated reflex), and then through voluntary action of the external sphincter and the levator ani.

- Thirdly, rectal relaxation and compliance enable the sensation of urge to dissipate and the internal sphincter to resume its tonic contraction, thereby allowing the striated mechanism to relax.

Defecation

Defecation

During defecation, stool is expelled from the rectum through a relaxed pelvic floor and a relaxed anal sphincter. The normal sequence of events is as follows:

- Firstly, the arrival of feces in the rectum triggers the stretch receptors, rectal contraction, and internal sphincter relaxation.

- Secondly, after the initial acquired reflex contraction of the external sphincter, and then the decision to evacuate, the external sphincter and puborectalis relax, opening the anorectal angle.

- Thirdly, intra-abdominal pressure is increased actively, normally through inspiration and/or activity of the transversus abdominis muscle.

- The pelvic floor then descends, and the rectal contents are expelled with the help of a rectal contraction and through a funneling process at the anorectum.

- Finally, the external sphincter, puborectalis, and internal sphincter resume their resting tone.

Anorectal Disorders

Anorectal Disorders

Physiotherapy may be indicated for any of three major problems in this area: incontinence, evacuation difficulties (constipation), and pain.

Incontinence

Incontinence

Incontinence is the involuntary loss of rectal contents, whether solid, liquid, or gaseous. It may be of anal or of rectal origin, or is sometimes caused by diarrhea, due to cramping and decreased stool consistency [Louis and Valancogne 1987]. It is not uncommon for patients to present with combined fecal and urinary incontinence [Lacima and Pera 2003].

Incontinence of anal origin may be due to hypotonicity of the anal sphincter, characterized by low resting pressure (less than 40 mmHg). It is often a problem of the internal (smooth) sphincter and may lead to soiling of the undergarments, especially with prolonged weight-bearing. On the other hand, with insufficiency of the striated sphincter, there may be a more complete involuntary evacuation, and decrease in active control. Investigation may show decreased electromyographic activity.

Incontinence of rectal origin may be due to decreased rectal compliance, leading to a sudden urge to expel stool [Madoff et al. 1992]. This may be encountered with or without rectal hypersensitivity, where the urge to expel quickly is paramount.

Incontinence may also be caused by rectal hyposensitivity. Rectal hyposensitivity may lead to the accumulation of large amounts of hardened stool in the rectum, and this may form a hardened mass called a fecaloma. Incontinence may result, due to prolonged relaxation of the internal sphincter and eventual seepage of liquid stool around the fecaloma. Rectal hyposensitivity may also lead to increased rectal compliance and an enlargement of the functional rectum.

Constipation

Constipation

Normal toileting habits vary widely. While a great many people evacuate once per day, normal ranges are from three times per day to one evacuation every 3 days [Devroede 1993]. Constipation may include decreased intestinal motility (slow transit), obstruction, and/or functional difficulty with evacuation.

With functional evacuation difficulties, the causative dysfunction may again be located at the level of the anus or at the level of the rectum. Constipation of anal origin may be due to hypertonicity at the anal canal or due to a rectosphincteric (striated) dyssynergy. Patients with this type of dysfunction not only fail to relax the sphincter during attempts at evacuation, but they may also actually contract the sphincter and pelvic floor, thereby inhibiting the passage of stool [Rao 2001, Rao et al. 2004].

With constipation of rectal origin, prolonged and excessive storage of fecal material in the rectum may have led to rectal dilation and thus to hyposensitivity and hypocontractility. This type of dysfunction is often due to prior constipation of anal origin [Kerrigan et al. 1989, Chang et al. 2003].

Pain

Pain

Pain syndromes in this area may be due to local pathology, hypertonicity of related musculature, fissures, abscess, fistula, hemorrhoids, or local irritation of the skin or mucosa. It may also be referred from the viscera, the bony pelvis, from spinal levels, and sometimes from the lower extremities [Travell and Simons 1983, Steege et al. 1998, Wise and Anderson 2003].

Related Pathologies

Related Pathologies

There are several pathologies that may eventually lead a patient to consult a physiotherapist for anorectal disorders. The following is an alphabetical and by no means exhaustive list of some commonly seen problems [Whitehead et al. 1999]. It is the responsibility of the physiotherapist to obtain a basic understanding of each patient’s individual pathology before embarking on a treatment plan.

- Anismus

- – Functional disturbance, contraction at the anal sphincter during efforts to evacuate stool [Rao et al. 2004].

- – Drossman found that patients with functional disorders were more likely to report severe sexual abuse or frequent physical abuse than those with organic disorders [Drossman et al. 1990, Drossman 1994].

- – Functional disturbance, contraction at the anal sphincter during efforts to evacuate stool [Rao et al. 2004].

- Coccygodynia

- – Coccygeal, sacrococcygeal, rectal, and/or anal pain [Theile 1963].

- – Usually increased in standing and sitting, in the evening, and with fatigue

- – Coccygeal, sacrococcygeal, rectal, and/or anal pain [Theile 1963].

- Colorectal cancer

- – This has a large hereditary component.

- – The indication for physiotherapy may be postsurgical (e. g., with a rectal reservoir)

- – This has a large hereditary component.

- Crohn’s disease

- – An inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

- – Inflammation in the small intestine, usually the ileum.

- – Usual symptoms: pain and diarrhea.

- – An inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

- Descending perineal syndrome

- – Commonly related to excessive pushing at childbirth.

- – May be caused by abnormal evacuation habits, such as excessive straining against a closed anorectal angle and anal sphincter.

- – The result is descent of the perineum, which eventually leads to stretching of nerve trunks and microtrauma to pudendal nerve endings.

- – Progressively leads to neurogenic muscular lesions, responsible for incontinence [Lubowski et al. 1988, Meunier 1987].

- – Typically characterized by fecal incontinence associated with difficult voluntary evacuation.

- – Sex ratio (female to male): 9 : 1.

- – Commonly related to excessive pushing at childbirth.

- Diabetes

- – Peripheral nerve damage may lead to decreased rectal sensitivity and/or sphincteric deficiency.

- Encopresis

- – Almost continuous loss of liquid and semi-solid fecal matter.

- – Affects 1–2 % of children under the age of 7.

- – Due to fecaloma, which causes constant stimulation of the anorectal inhibitory reflex, thereby relaxing the internal sphincter and causing fatigue to the external sphincter [Valancogne 1993].

- – The anal canal remains open, but fecaloma blocks the passage of solid material.

- – The outer surface of the fecaloma liquefies with heat, and mixes with secretions from the rectal mucosa.

- – Almost continuous loss of liquid and semi-solid fecal matter.

- Fissure

- – An anal fissure is a small tear or cut in the skin that lines the anus.

- Fistula

- – A fistula is a small abnormal channel or tract that may develop in the presence of inflammation and/or infection.

- Hemorrhoids

- – Varicosities formed by the enlargement of anastomoses at the junction of the superior, middle, and inferior rectal veins.

- – May be asymptomatic, or may cause itchiness or bleeding.

- – If thrombosed, they may cause very painful lumps.

- – Skin flaps may persist once the hemorrhoid has been resorbed.

- – Varicosities formed by the enlargement of anastomoses at the junction of the superior, middle, and inferior rectal veins.

- Hirschsprung’s disease

- – Aganglionic megacolon.

- – Absence of internal sphincter relaxation during rectal filling.

- – Congenital, most often found in males.

- – Common in children with Down’s syndrome.

- – Aganglionic megacolon.

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- – Absence of organic and metabolic gastrointestinal abnormalities.

- – Abdominal pain.

- – Irregular bowel habits, colonic and/or rectal spasm.

- – Emotions may play a role [Welgan et al. 1988].

- – May lead to poorly distensible rectum.

- – Absence of organic and metabolic gastrointestinal abnormalities.

- Rectal prolapse

- – The rectum herniates into the anus and beyond.

- – Mucosal prolapse: may extend 3–4 cm beyond the anus.

- – Total prolapse: cylindrical prolapse 8– 15 cm in length.

- – The patients often have history of perineal hypotonus, absence of pelvic floor contraction on effort, and especially difficulty in evacuation.

- – constipation

- Rectocele

- – Sometimes asymptomatic, but often associated with difficulty in evacuation.

- – Grade 1: bulging of the posterior wall of the vagina.

- – Grade 2: bulging of the posterior wall of vagina, to the vulva.

- – Grade 3: part of the posterior wall of the vagina is exteriorized.

- Surgery

- – Postsurgical conditions such as: hemorrhoidectomy, repair of rectocele, prolapse repair, fissurectomy, fistula repair, colostomy, bowel removal, bowel reconstruction (reservoir), polypectomy, sphincter repair.

- – The rectum herniates into the anus and beyond.

Specialized Tests

Specialized Tests

Among the various examination procedures and tests for patients with anorectal problems, colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy, and laboratory tests are carried out to exclude associated pathologies. Many other tests can provide an evaluation from the functional point of view and can thus be of great help to the physiotherapist. Most of these tests are prescribed by the specialist or general practitioner.

One such test is anorectal manometry, which provides information about the pressures generated in the rectum and anal canal, making it possible to define functional disturbances at the rectum or at one or both sphincter muscles. Multichannel catheters can be used to assess the entire length of the anal canal in all directions [Meunier and Gallavardin 1993]. Manometry measures the resting pressure of the anal canal, 80% of which is produced by the internal sphincter (N = 40–80 mmHg). It also measures the squeeze pressure of the anal canal, produced by the external anal sphincter (resting pressure + 40–80 mmHg, held for 20 s).

With the help of an inflatable balloon, anorectal manometry can verify the integrity of the rectoanal inhibitory reflex, which is absent or diminished in Hirschsprung’s disease. In addition, anorectal manometry measures rectal volumes, including the smallest perceptible volume (N = 15–25 mL), the sensation of an urge to evacuate (50–100 mL), and the maximal tolerable volume (220–240 mL). Normal ranges vary.

Another testing procedure is electromyography. This evaluates the action potentials of the external anal sphincter at rest and during squeezing and Valsalva maneuvers. Needles must be inserted for precise measurements, but this is controversial, as the results may be affected by pain reflex mechanisms.

Pudendal nerve latency testing evaluates the interval between direct stimulation of the pudendal nerve and the resulting contraction of the external anal sphincter [Lubowski et al. 1988].

Defecography is functional radiographic evaluation of the rectum and anal canal, using contrast medium. Imaging is carried out of the resting position, dynamic squeezing, and dynamic evacuation. This test evaluates the anorectal angle, N = 90h at rest and 140h during defecation. It demonstrates the relative opening of the anal canal, the descent of the pelvic floor, and the resulting vacuity of the rectum. It can also show the closing of the anal canal and anorectal angle during attempts to squeeze. Prolapse of the rectal mucosa, prolapse of the rectum, and rectocele can be demonstrated with this test.

Colonic transit studies are done to estimate the amount of time it takes for a patient to digest food. Patients are asked to swallow radiopaque markers, and the transit time is subsequently observed by periodic radiographs.

Magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography are also continually developing and progressing, allowing detailed anatomic and functional evaluation of the organs, pelvic floor, and related structures [Eguare et al. 2004].

Physiotherapy Evaluation

Physiotherapy Evaluation

To allow a full understanding of the extent and nature of each patient’s problem, and to subsequently establish an appropriate and precise treatment plan, the physiotherapy evaluation must take into consideration the patient’s diagnosis, the results of relevant tests, a detailed interview, and a thorough clinical examination.

Interview

Interview

The initial questionnaire provides valuable information about the patient’s history and symptoms, evacuation habits for urine and for stool, and the impact that the patient’s problem has on his or her lifestyle. It is during this initial interview that a relationship of confidence is established between the therapist and the patient, which is essential for the success of the treatment and training regimen [Brown 1998].

The interview follows the same guidelines as those for patients consulting for urinary incontinence (see pp. 353–355), with particular focus on information relating to the anorectum. Details of the patient’s regular evacuation habits are noted, including the patient’s general evacuation routine and how easy it is for the patient to evacuate. The patient’s habitual posture and position for evacuation, the thoroughness and the timeliness of the process, and the technique used are discussed. It is also important to have information about the fecal consistency and about any prescription or over-the-counter drugs that are used to modify the consistency or assist in evacuation.

The patient is questioned about diet. The ingestion of liquids and solids, fruit and fiber, the frequency and timing of meals, and snacking habits are all relevant to the discussion. Many patients will have already identified problem foods (those that lead to constipation or incontinence) as well as “helpful” foods.

If the patient has incontinence, the frequency and degree of the incontinence are discussed, as well as the use of protective padding or garments. If the patient has pain, the initial onset, incidence, degree and type of pain are discussed, as well as the usual mechanism of exacerbation (e. g., following evacuation for stool or related to stressful situations) and established means of relief.

Finally, information can also be obtained during initial interview regarding the patient’s psychological profile and whether or not this may be affecting the patient’s situation.

Physical Examination

Physical Examination

The physical examination includes a postural assessment, a scan examination of the spine and bony pelvis, and a detailed evaluation of the pelvic floor structures. Proprioception and sensation, pelvic floor muscle tone and contractility, elasticity of tissue, and relationships between the pelvic floor musculature and adjacent pelvic viscera are assessed here. The relative positions of the pelvic organs and any prolapse are also noted. With surface palpation and internal palpation at the vagina and at the anus, the experienced physiotherapist is able to obtain an impression of the tonus of the superficial layer of the perineal musculature and to evaluate muscular activity and tonus in the left and right portions of the pubococcygeus sling, as differentiated from the left and right iliococcygeus and coccygeus muscles in most patients [Caufriez 1988, 1989, DeLancey 2002]. This evaluation includes assessment of the relative strength of the muscles, the speed of muscle recruitment, and the endurance of the muscle groups [Brown 2001].

The pelvic floor response during functional activity is evaluated, with an impression of the production and result of intra-abdominal forces. The downward (inferior) movement of the viscera during increases in intra-abdominal pressures should not be excessive, and the upward (superior) movement should be visible during a pelvic floor contraction and during maneuvers that reduce intra-abdominal pressure. Reflexes, proprioception, pain, and sensitivity are also evaluated.

The pelvic floor examination in patients with anorectal disorders is the same as that for patients consulting for urinary incontinence, with special focus on details relevant to the anorectum (see also section 4.4, p. 405).

Observation of the skin surface at and around the anal sphincter provides information about secretions, irritation, and exteriorized hemorrhoids. Observation of the resting position of the anal sphincter provides information about the tone of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter.

Anal palpation allows evaluation of the length of the anal sphincter, as well as its resting tone and contractility. The anorectal angle can also be estimated; it is normally between 60h and 130h. The presence of feces in the rectum and its consistency can be determined at this point, and the tone and contractility of the posterior portions of the pelvic floor musculature (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, iliococcygeus, and ischiococcygeus) can be evaluated. As the coccyx is an important point of attachment for the pelvic floor musculature and its related fascia, the position and mobility of the coccyx are also assessed, and painful areas can be palpated.

The presence and degree of rectocele are easily assessed during anal palpation, as the palpating digit presses anteriorly and slightly inferiorly into the posterior vaginal wall.

Palpation and functional testing of the abdominal wall is also valuable, including palpation of the colon and observation of points of tenderness. Abdominal activity is noted during functional activities such as coughing or raising of the upper trunk or lower extremities. Breathing patterns and the movement of the respiratory diaphragm are also evaluated, and, if indicated, a more detailed evaluation of the thoracolumbar spine and pelvis can be carried out in order to obtain a better appreciation of the functional abdominopelvic mechanism as a whole [Neumann and Gill 2002].

|

Physiotherapeutic Approach

Physiotherapeutic Approach

Both constipation and incontinence can be of anal or of rectal origin. The treatment provided for either is in accordance with the findings of the evaluation. Typically, incontinence is related to reduced contractility of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter, and/or increased rectal sensitivity and reduced compliance. It may also be related to constipation due to encopresis and reduced rectal sensitivity. Constipation of a distal nature, as opposed to constipation due to slow transit, is often related to abdominopelvic dyssynergia during attempts at evacuation, hypertonicity of the pelvic floor, rectocele, and/or reduced rectal sensitivity.

Pain syndromes are often related to pelvic floor hypertonicity and should be treated accordingly. Descending perineum syndrome is sometimes the cause of pain.

Once the initial interview and clinical examination have been conducted, a qualified physiotherapist is able to establish a list of problems and set the goals of treatment in accordance with it. Table 6.3 lists potential problems that may be found.

Treatment

Treatment

Various physiotherapy treatment options are available, including:

- Patient education

- Exercise

- Manual techniques

- Biofeedback

- Electrical stimulation

- Balloon techniques

- Functional applications

The approach to the treatment of anorectal disorders is multifaceted and the decision regarding a treatment approach has to take into account contractility and control at the pelvic floor and the anus, sensitivity and compliance at the rectum,

Although each patient’s needs differ, patients can typically be seen once a week, and are given instructions and exercises to do at home between treatments. A change should become evident within four to six treatments, and the total length of treatment will depend on the disorder.

Information

One can start to provide the relevant information at the initial interview, when the discussion centers on bowel and bladder habits, diet, and general health. Later, with the use of a pelvic model, diagrams, information leaflets, and an evacuation diary, the patient obtains a basic understanding of the gastrointestinal system and its functioning, with particular emphasis on the control that can be exercised via the pelvic floor musculature. Discussed with reference to the patient’s own symptomatology, this will help motivate the patient for his or her functional rehabilitation work. Combined with pelvic floor retraining, this information allows the patient to learn how and when to use the muscles for continence and for evacuation.

Straining during defecation is discouraged, in order to decrease undue pressure on the bladder, pelvic floor, and pudendal nerve and its branches. Patients who have difficulty in evacuating without straining are instructed to use an evacuation technique that encourages relaxation at the anal sphincter, combined with the use of the respiratory diaphragm as a piston to gently increase intra-abdominal pressure. This technique alone often results in successful evacuation, but if more pressure is necessary, patients can be taught to use the transversus abdominis musculature to increase the pressure and to direct the force posteriorly. Using the transversus abdominis musculature can also be encouraged for postural reasons and to provide stabilization during strenuous activities [Valancogne 1993].

Providing information about bowel routine is also important [Norton 2004]. For patients who suffer episodes of incontinence, it is a good idea to try to evacuate completely before leaving the house in the morning. This will ensure an empty rectum for at least the beginning of the day, and will reduce episodes of incontinence. The patient is encouraged to try to evacuate at the same time each day—for example, approximately 20 min after breakfast—in order to take advantage of the peristaltic activity brought on by the gastrocolic reflex. To assist evacuation, the patient can be instructed to include stimulating foods at breakfast and to carry out an abdominal massage. Again, the proper evacuation technique is essential.

A discussion about diet is another part of the information process. Although referring the patient to a dietician would be ideal, it is not always practical, and it is therefore often the physiotherapist who must discuss this topic with the patient. Patients can be encouraged to follow guidelines such as the Canadian food guide [Health Canada 1997], drink six to eight glasses of water per day, and ensure adequate fiber intake. The aim is to achieve an optimal fecal consistency.

It is recommended that constipated patients should consume adequate amounts of fruits and vegetables (especially greens), as well as cereals, grains, and whole-wheat bread. It should be emphasized that the fluid intake has to be increased along with the increased fiber intake. While each individual may react differently to different foods, it is often found that beans, peas, potatoes, pasta, and white bread lead to harder feces and should be avoided by patients with constipation. Most patients with incontinence often have a problem with loose stools. Often, they will already have recognized their “problem” foods, which may include onions and foods from the cabbage family. For these patients, white rice, raw carrots, mashed potatoes, and ripe bananas are encouraged—although, again, these foods may result in different reactions in different patients. Many products are available, both by prescription and over-the-counter, to promote the optimal fecal consistency—which is soft and bulky, with normal motility and good volume. Although these products are beyond the scope of the present chapter, some that may be used include:

- Laxatives—e. g.,lactulose(Duphalac)—decrease pH in the colon, causing stimulation of peristaltic activity and water retention in the feces.

- Bulk-forming agents—e.g., Metamucil—promote peristalsis in the intestine and increase the fluid and fiber content of the feces. This produces larger, bulkier stools for more complete evacuation.

- Anti-diarrhea agents—e.g., loperamide (Imodium)—reduce motility and promote the absorption of fluids in the intestine.

Exercises

Exercises

If patients are to take an active part in the treatment process, they have to learn to identify and control the muscles of the pelvic floor, as well as the abdominal musculature.

Whether the patient is consulting for pain, incontinence or constipation, he or she may have difficulty in identifying and contracting the anal sphincter and levator ani. Exercise helps to improve the proprioception of these muscles and subsequently to improve both their contraction and relaxation. The patient has to have a strong pelvic floor and sphincter in order to control stool and should be able to identify and relax these muscles in order to evacuate stool. Patients consulting for pain that is related to hypertonicity need to become aware of increased muscle tone and should be able to relax the muscles to prevent or reduce the pain.

Pelvic floor muscle exercises therefore have to include proprioceptive exercises, exercises providing training in strength, endurance, and recruitment speed, and exercises promoting relaxation of the musculature. Once patients have started training for these parameters, they should be instructed in functional applications of the exercises. For example, a patient who is prone to sudden urges to defecate can use “speed” contractions to recruit the musculature quickly when control is needed. Endurance-type contractions can also be used to make the urge dissipate. Patients who have trouble evacuating can practice relaxation of the musculature to allow for the passage of feces.

The abdominal musculature, particularly the transversus abdominis, is instrumental in helping generate adequate pressure for fecal expulsion. Also, during activities that result in increased intra-abdominal pressure, a contracting transversus will ensure that the pressure is well distributed over the posterior part of the pelvic floor. If the transversus does not contract, there is an expansion at the abdominal wall and an increase of pressure in the anterior portion of the intra-abdominal cavity. With exercise, patients can learn to train the abdominal musculature to work for an efficient and complete evacuation.

Part of the exercise program is the evacuation technique. Patients are taught the technique as a step-by-step procedure, starting with the first two or three steps and then the addition of the subsequent steps. The details are given below.

Evacuation Technique

- Adopt the evacuation position: firmly seated on toilet, with feet fully supported and hips flexed more than 90.

- Localize and relax the pelvic floor and anal sphincter by gently contracting the area for 3 s and then relaxing for 5 s. Do this three times.

- Breathe in diaphragmatically, relaxing the abdomen to allow distension, and hold for 5 s. Do this five times.

At this point, evacuation may have already begun.

- Hold the breath and concentrate on continuing to relax the sphincter and pelvic floor until evacuation is complete.

- The push can be improved by preventing abdominal distension during diaphragmatic respiration. Place a binder across both the anterior superior iliac spines to prevent the abdomen from distending. This will direct the forces more posteriorly over the anus.

- Later, instead of using a binder, use the transverses abdominis, with or without manual assistance, to prevent abdominal distension.

- Forced expiration, by breathing out fully into a semiclosed fist and contracting the transversus, may further assist in evacuation.

It should be noted that opinions vary regarding the proper use of the transversus abdominis muscle in the evacuation technique [Chiarelli 2002].

Manual Techniques

Manual Techniques

The physiotherapist can use manual techniques to achieve several treatment goals [Brown 2001]. At the level of the pelvic floor, these techniques are instrumental in improving proprioception, in facilitating the musculature, in strengthening and normalizing the tone, and in modifying pain. For women with anorectal problems, many techniques are performed vaginally, as this is often more comfortable and provides easy access to the pelvic floor (see pp. 144–146).

Other specific techniques, such as coccygeal mobilization and anal sphincter dilation, are carried out anally. Directive pressures can also be used on the surface of the perineum to help confirm for the patient when the proper evacuation technique has been achieved, or to facilitate a pelvic floor contraction (digital biofeedback).

Intestinal or abdominal massage is a manual technique that is performed by the physical therapist during treatment sessions, and the patient can be taught how to do it at home as well. The technique involves applying firm pressure on the abdomen in the area of the colon, following it in a clockwise direction. This is a two-handed technique, with one hand following the other to promote intestinal motility. Pressures are first applied above the right anterior superior iliac spine, and directed superiorly to the right hepatic flexure just below the rib cage. This is followed by applying pressures in a transverse direction, from right to left, to follow the transverse colon. Finally, pressures are applied in an inferior direction, from the left splenic flexure downward and slightly medially, to follow the descending colon to the area of the sigmoid colon and rectum. Points of resistance can be palpated throughout this path, and these points can be treated with circular pressures, deeper mobilization, and vibrations. The massage procedure should take 10–15 min.

Active hip and knee flexion to compress and decompress the abdominal contents can also be used to encourage peristalsis and the evacuation of stool and gas.

Biofeedback Using Instruments

Biofeedback Using Instruments

Many patients have difficulty in performing a pelvic floor contraction correctly. This is often due to a lack of understanding of the orientation and function of these muscles, but can also be caused by weakness, injury, or dysfunction. Additional factors include social taboos and the relatively concealed location of these muscles. Biofeedback allows patients to visualize the musculature and see immediately the changes that they are able to accomplish in the muscular activity [Miner et al. 1990, Tries 1990, Trunnell 1991]. For many patients, biofeedback makes pelvic floor training more interesting and easier to perform [Trunnell 1991].

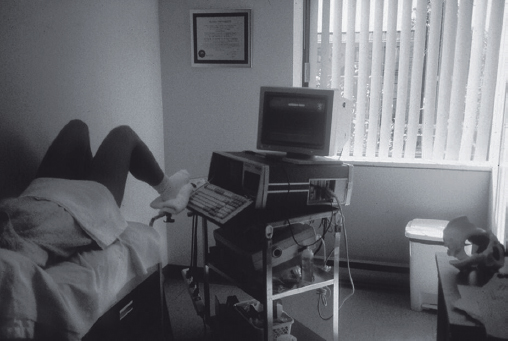

During biofeedback, a physiological response is monitored and displayed. When the patient attempts to change the response, any difference is immediately measured and displayed back to the patient. For pelvic floor retraining, muscular activity can be monitored through its electromyographic activity, via surface electrodes placed on the perineum or by using an intracavity vaginal or anal probe [Norton et al. 2003, Battaglia et al. 2004]. Alternatively, a mechanical probe can be used in the vagina or in the anal canal to detect changes in pressure gradients as a result of changes in pelvic floor muscle activity. Various methods used to display the changes in activity include sound, a light bar, a digital read-out, and graphics on a computer monitor (Fig. 6.6).

Although it is known that the pelvic floor musculature contracts in synergy with the abdominal musculature [Neuman and Gill 2002], it is often observed that many patients inadvertently overuse the abdominal muscles in attempting a pelvic floor contraction. For this reason, electromyography surface electrodes can also be placed on the abdomen, over the abdominal muscles, in order to screen for exaggerated contractions. Later, this electrode placement can also be used to help train abdominopelvic synergies—for example, when ensuring a pelvic floor contraction during increases in intra-abdominal pressures such as coughing or actively contracting the abdominal muscles.

Throughout the training and when planning the exercise regimen, the physiotherapist should aim to train the speed of the contraction and the endurance of the muscle, as well as the contraction strength, to achieve optimal use of the fasttwitch and slow-twitch muscle fibers. Biofeedback can be particularly useful in these cases. For example, it may be easier for a patient to train for a strong pelvic floor contraction, such as that required to prevent incontinence during a cough, if she is able to see the increased activity on the biofeedback screen. Alternatively, a patient who requires endurance training will be able to understand the concept better if she can see the activity of her lower-grade, longer-duration contraction displayed visibly. It is also easier to train the speed of muscle fiber recruitment by attempting quick, successive contractions within a time frame clearly defined on the monitor.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree